Haitian oligarch Réginald Boulos, once an enthusiastic supporter of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse, had a falling out with him in the summer of 2018.

Early in his mandate, Moïse prioritized Boulos’ companies for investment using state funds. Ayibopost notes that Boulos’ “Auto Plaza was among the three companies benefitting from the first big contract signed during the Jovenel Moïse era. The company then received more than $53 million for the purchase of heavy equipment in 2017.”

Boulos told the Haitian Times that he broke off his relationship with Moïse in 2019. While he did write a letter published in Le Nouvelliste in June 2019 demanding Moïse resign, the timeline Boulos presents to The Haitian Times seems to contradict his past statements.

In July 2018, following Moïse’s hiking of fuel prices due to an IMF pressure, massive protests rocked Port-au-Prince. Protestors vandalized and set fire to many businesses, including some owned by Boulos.

Protestors attacked his Nissan dealership and Delimart grocery store. In a public Jul. 19, 2018 letter, Boulos made it clear he did not think these attacks were random. He wrote that the attacks on his businesses were “coldly concocted and carried out under cover of the actions of disgruntled crowds.”

According to Boulos, these attacks “constitute the worst injustice done to a man who has spent his life creating jobs and today employs more than 2,000 of his brothers and sisters.” Boulos insisted that acts of arson targeting his businesses were the result of “the malicious action of criminals under contract.”

Appealing to his fellow Haitians, Boulos wrote in his statement that “things must change for the good in our country. We will have to take into account the legitimate demands for betterment emanating from the poor and marginalized categories of our people,” clearly alluding to efforts to oust Moïse from power.

Boulos’ interpretation of events, that his properties were deliberately attacked by “criminals under contract,” was not widely held.

On Jul. 3, 2021, Boulos had released a statement accusing Moïse of weaponizing the judicial system against him. Four days later, on Jul. 7, 2021, Jovenel Moïse was assassinated in his home.

Later that day, The Haitian Times posted an interview with Boulos where he denied speculation that he was involved in the assassination.

Moïse was assassinated by a squad of 28 foreign mercenaries, including two Haitian-Americans and 26 Colombians. One of the Haitian-Americans is James Solages, who worked as the chief of bodyguards for the Canadian Embassy in Haiti. The Haitian Times reported that, according to many social media posts, Solages also used to work as a security guard for Réginald Boulos.

In an interview with Jacobin, journalist Kim Ives noted that the assassination “may have required more money than one family could have provided,” pointing to the possible involvement of several oligarchs, including Boulos and Dimitri Vorbe. Ives argued that “the assassination is meant to get into power a president who will do the bidding of the bourgeoisie.”

Indeed, with Moïse out of the way, charges from the ULCC and ONA were dropped. Boulos had left Haiti a week earlier, on Jun. 25.

In the U.S., a day after Moïse’s assassination, Boulos began hiring public relations consultants. He re-hired Art Estopinan, former Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen’s (R-FL) chief of staff, to work for him as a lobbyist.

According to Politico, Estopinan planned to “lobby lawmakers, including members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the House Foreign Affairs Committee, and the House Haiti Caucus, as well as the Biden administration.” Estopinan explained that Boulos wanted Estopinan to “help him in Washington to promote a vision of his political party.”

Boulos had other advisors working for him in the U.S. According to Politico, this team included Novitas Communications, which handles public relations for Boulos, and the consultant Joe Miklosi, who led fundraising efforts for Boulos in the U.S.. Boulos said he hired the team to lobby the Biden administration.

“I don’t feel the opposition today would have the capability to pull out such a well-organized mission,” Boulos told The Haitian Times.

Ariel Henry, the prime minister Moïse had nominated but not inaugurated two days before his murder, emerged from hiding a few days after the murder. He was selected to run Haiti by the U.S. and CORE Group of ambassadors via a tweet and accompanying statement by the United-Nations diplomatic mission in Haiti, BINUH. Henry was sworn in as the prime minister on Jul. 20, 2021, three days after this statement was released.

As the leader of MTVAyiti, Boulos then signed Ariel Henry’s “September 11 Accord.” Boulos had found a leader he could support. Boulos’ support for Henry’s Accord caused outrage among some in his new party. In a letter to his party dated Aug. 1, 2022, Boulos resigned as leader of MTVAyiti and left the party.

Boulos radicalizes Cherizier

In an interview featured in the documentary series “Another Vision”, Jimmy Cherizier claimed that Boulos had approached him to burn down the rival Toyota dealership across the road from his Delmas 6 neighborhood. Cherizier refused.

Cherizier had come to Boulos’ attention as a neighborhood defense group leader who had successfully forced out criminal gang members from lower Delmas with the help of other PNH officers. He had not yet organized or declared the FRG9 nor had he been cast as a “gang leader” by local human rights groups.

Cherizier and other residents of lower Delmas established a community organization named Another Vision (from which the documentary gets its title). The organization solicited donations, and Réginald Boulos made one.

Cherizier says he was unaware at the time of Boulos’ anti-democratic history of backing the 2004 coup and the human rights violations associated with the Group of 184.

Cherizier explains that Boulos’ request that he burn down the Toyota dealership was a radicalizing moment for him. A class consciousness began to emerge. In June 2020, he described Haiti’s “stinking, rotten, corrupt system” serving the bourgeoisie. In another interview a month later, Cherizier said “there is no bigger gang than that Syrian-Lebanese mafia bourgeoisie which has taken the nation hostage. And no-one has more guns than they have. They have all the money, and we have none.”

Nor was Cherizier aware at the time that Madistin was hired by NCHR-Haiti (RNDDH) in 2004 to represent the so-called victims of the manufactured La Scierie massacre, another telling fact revealed in the documentary “Another Vision.”

Some have interpreted this donation from Boulos to the Another Vision organization as evidence that Cherizier was a leader of a paramilitary group willing to work for Haitian oligarchs. That formulation omits crucial evidence to the contrary.

Once Boulos’ relationship with Cherizier ended in the summer of 2018, he formed new relationships with criminal gangs. In an October 2019 interview, Boulos admitted to supporting criminal gangs who are associated with the G-Pep criminal gang federation, responsible for virtually all of the kidnappings in Haiti, along with other violent crimes like murder, rape, and extortion.

On Nov. 16, 2018, FJKL published their preliminary report on the violence that occurred in La Saline on Nov. 13, 2018. FJKL presented the attack as a battle between two gangs, also alleging that Cherizier had “reinforced” (without more detail) the gang of the victorious Serge Alectis alias “Ti Junior.” Tacked on at the end, almost as an afterthought, is the sentence: “It is the massacre of La Saline,” without more explanation.

Exactly one year later, in November 2019, Boulos’ new political party, MTVAyiti, funded and organized a series of events on the anniversary of the La Saline massacre. This popularized the FJKL and RNDDH allegations that Cherizier was somehow linked to the deaths of 23 or more victims. The MTVAyiti “memorial day” for the La Saline victims was part of Boulos’ political campaign against Moïse.

Weeks before the memorial, in September 2019, Boulos referred to Moïse as an “imposter” and a “living restavek ” of former president Michel Martelly.

A month later, in October 2019, Moïse announced an increase on interest rates for loans from the ONA over 50 million gourdes to 20%. This would directly affect Boulos.

Réginald Boulos shows concern for victims of political violence?

Was Réginald Boulos motivated by compassion for poor Haitians victimized by violence to organize a day of commemoration of the so-called “La Saline Massacre”? The historical record suggests he was not.

Attacks on Lavalas supporters before and after the 2004 coup caused some to take up arms to defend their communities. These community defense groups were often portrayed by coup-supporters, the coup regime, and Western mainstream media as “criminal gangs.” One of these militant, pro-Lavalas community leaders was Emmanuel “Dread” Wilmer, based in Cité Soleil, one of the poorest parts of Port-au-Prince.

In an article for The Nation and Haïti Liberté, Dan Coughlin and Kim Ives noted that the residents of Cité Soleil saw Wilmer “as a hero defending them from pro-coup paramilitaries (who in 1994 burned many houses in the rebellious shantytown) and UN occupation troops.” He was a cherished leader who championed the community of Cité Soleil who, according to Haiti Action Committee’s Seth Donnelly, views itself as locked “in a long-term struggle for the restoration of President Aristide and for the removal of occupation forces from Haiti.”

This put Wilmer and the residents of Cité Soleil at odds with oligarchs like Réginald Boulos and Andy Apaid, a prominent sweatshop owner and leader of the Group of 184, in which Boulos was also active. The Group of 184 was a so-called civil society ”coalition, created and supported by the NED that helped lead a destabilization campaign against Aristide until the latter’s ouster in the 2004 U.S.-backed coup.”

An analysis of Wikileaked-State Department cables by Haïti Liberté’s Ansel Herz revealed that “Apaid was financing an anti-Aristide gang in Cité Soleil led by Thomas Robenson, alias Labanyè, a gang leader.”

Aiming to create a justification for further PNH and MINUSTAH violence in Cité Soleil, Apaid paid Labanyè to terrorize Cité Soleil residents. The violence was then blamed on Lavalas militants like Wilmer.

After Labanyè was killed, these business elites had to find alternative means to eradicate Lavalas militancy from Cité Soleil. Another Wikileaked cable revealed that Haitian oligarch Fritz “Mevs told the [U.S.] Embassy that Réginald Boulos had “distributed arms to the police and had called on others to do so in order to provide cover to his own actions.”

Boulos was also eager to have MINUSTAH forces “cleanse” Cité Soleil of Lavalas militants. In an article for New Left Review, Justin Podur pointed out that “MINUSTAH’s civilian head of mission Juan Gabriel Valdés came under increasing pressure from Haitian business elites to resume the offensive.”

Boulos told Radio Métropole listeners on Jan. 5, 2006: “We are waiting for [Valdés] to give clear instructions to the troops under his command to cleanse Cité Soleil of the criminals, like they did in Bel Air. You cannot make an omelet without breaking eggs. We think that MINUSTAH’s generals need to make plans to limit collateral damage. But we in the private sector are ready to create a social assistance fund to help all those who would be innocent victims of a necessary and courageous action that should be carried out in Cité Soleil.”

Boulos was also eager to have MINUSTAH forces “cleanse” Cité Soleil of Lavalas militants.

On Jul. 6, 2005, MINUSTAH forces raided Cité Soleil. MINUSTAH’s intended target was Wilmer. What resulted was a massacre of at least 20 civilians, with another 26 wounded, including women and children. Other residents and a legal advocacy group say 60 or more Haitians were massacred that day.

In an article for Haïti Liberté, Ansel Hertz explained that the “battle for Cité Soleil continued over the next 18 months, with the toll of dozens of ‘unintentional civilian casualties’.”

So it seems unlikely that Boulos paid for the lavish 2019 rally out of concern for the residents of La Saline, long a Lavalas stronghold.

FJKL report on La Saline

In November 2018, FJKL had been operating for five months as a human rights organization. Their report, entitled “Situation de Térreur à La Saline” (Situation of Terror in La Saline) is their first human rights investigation.

Based on what is available online, this was FJKL’s third publication. It followed one commentary piece and an open letter to then Prime Minister Jean-Henry Céant.

The commentary piece, published in September 2018, focused on an Apr. 6, 2018 order from Judge Jean Wilner Morin to pursue an investigation into possible money laundering by the Aristide Foundation for Democracy (AFD).

Considering Gilles’ alleged role in an attempt to frame Yvon Neptune, and Madistin’s role as a lawyer hired by Éspérance and NCHR-Haiti (RNDDH) to represent the “victims” of the manufactured la Scierie massacre to frame Fanmi Lavalas leaders, this choice to focus on the AFD reads as evidently political.

At the time of the report, the Petrocaribe movement had begun, with Gilbert Mirambeau posting his now famous tweet asking the Haitian government “Kòt Kòb Petwo Karibe a???” (“Where is the PetroCaribe money ?”) in August 2018. This followed a Haitian Senate report from late 2017 that accused politicians of embezzling $1.7 billion via no-bid contracts given by the Haitian government between 2008 and 2016.

Somehow, in this context, Gilles and Madistin decided their new human rights organizations’ first case ought to be commentary on a judge’s order from April regarding alleged money laundering at the AFD. FJKL’s commentary claims the judge’s order against AFD “constitutes an important step in the fight against money laundering, corruption, and official impunity.” It would take FJKL another two months to produce a report on the Petrocaribe scandal.

The time FJKL required to produce these publications is an important factor as well. In the case of the commentary on the order by Judge Morin against AFD, several months passed between the FJKL’s founding and the commentary’s publication. There was also a period of several months between the Haitian Senate report on Petrocaribe and FJKL’s published analysis.

The Nov. 16 preliminary report on La Saline was released within 3 days of the violence in La Saline.

The FJKL report on La Saline is vague regarding sources of allegations. It does, however, provide a narrative that concludes that: a) the La Saline violence resulted from an attack by one gang against another and b) Jimmy Cherizier “reinforced” the attack.

It is significant that the three targets of FJKL’s first two publications were Aristide, Jovenel Moïse, and Jimmy Cherizier – all of whom were, at one time or another, opponents of Réginald Boulos.

FJKL’s deliberately omitted witness testimony that contradicts their report’s allegations

Mario Brunache, a Haitian-American Vietnam war vet and retired mail carrier lives in lower Delmas. He helped found the Another Vision community organization with Jimmy Cherizier in the spring of 2018. Brunache was interviewed by FJKL for their report on La Saline, but his testimony was omitted from the report. Brunache is one of several witnesses who say Cherizier was asleep at home when the attacks occurred in La Saline on Nov. 13, 2018.

FJKL not only omitted Brunache’s testimony. It didn’t bother to visit lower Delmas to interview Cherizier or the other witnesses who could testify that Cherizier was sleeping on a mattress on the floor of an apartment when radio reports claimed he was part of an ongoing attack in La Saline.

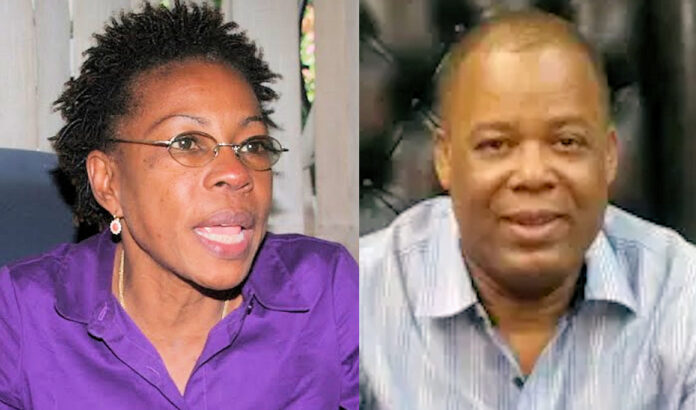

Madistin was challenged by journalist Kim Ives, co-director of the “Another Vision” documentary. Madistin claimed he didn’t have Cherizier’s address and that the neighborhood was too dangerous to visit anyway.

Madistin’s claim is patently untrue. Dozens of reporters from Western mainstream media have interviewed Cherizier in lower Delmas, unharmed. In fact, many journalists who visited FRG9 territory have remarked how secure and clean lower Delmas is, contrasting heavily with other neighborhoods ruled by G-Pep federated gangs. Cherizier credits donations from the Haitian diaspora for facilitating his tidy neighborhood.

Cherizier has accused FJKL (and the RNDDH) of bias and fabricating allegations against him. He told reporters that RNDDH and FJKL “are both political parties and not human rights organizations.”

Writer and long-time activist André Charlier agrees with this assessment, describing the RNDDH as a “political party with the facade of a human rights organization.” Charlier believes Cherizier is a “threat to petit-bourgeoisie” in Haiti like Pierre Espérance who he calls “anti-Haitian.”

The FJKL La Saline report alleges that Cherizier was involved put proffers no political motivation. It simply frames Cherizier as providing “reinforcement” for Nèg Chabon, the gang allegedly tied to the PHTK that attacked a rival La Saline gang on Nov. 13, 2018. That rival was the Projet La Saline gang, then led by Hervé Bonnet Barthélemy, alias “Bout Jean Jean,” who was close to Lavalas deputy Roger Millien.

The RNDDH La Saline report was the first to published allegations concocted by Millien that Cherizier had participated in a planning meeting with PHTK officials a few days before the La Saline violence. Millien admitted to knowing the leader of Projet La Saline gang, referred to in the FJKL report as Nèg anndan yo, located in the Kafou Labatwa/Fòtouron part of La Saline. In fact, Millien drove Bout Jean Jean and other gang members to Bernard Mevs hospital after they were wounded in early November, as reported by Le Nouvelliste and confirmed by Millien himself.

The understanding that Cherizier is the target of a disinformation campaign led largely by so-called human rights organizations is gaining momentum. In an interview with the New Yorker’s Jon Lee Anderson, Haitian Police Union leader Lionel Lazarre, “declined to disavow Barbecue.” Lazarre said Cherizier “was pushed into what he is now by human-rights organizations.”

FJKL has also targeted another leader who enjoys enthusiastic and widespread support from the local population: Jean Ernest Muscadin.

FJKL targets Jean Ernest Muscadin

In a Jun. 2, 2022 open letter to Justice Minister Berto Dorcé, FJKL accused commissaire (commissioner) Jean Ernest Muscadin of executing an accused gang member, Elvain Saint-Jacques, in Miragoâne. The allegation was based on a video that began circulating on May 30. FJKL demanded the resignation and the prosecution of Muscadin. Saint Jacques is better known by his gang handle, “Zo pwason.” He was a member of Izo’s Five Seconds gang, one of the most notorious and brutal kidnapping gangs in Port-au-Prince.

In an interview with Addicted Press, Muscadin said “what happened is not a mistake. I did it. They sent me a signal, I answered them. The bandits must know that they are not the only holders of the keys to death. They need to know that there are still people capable of standing up to them.”

Dorcé summoned Muscadin following the accusations. Muscadin then threatened to arrest Gilles if she stepped into Miragoane. He also implied that she was, in effect, siding with criminal gangs.

Seemingly undaunted by threats from Henry’s de facto government, Muscadin stated that “as long as I am commissaire of Miragoâne, my jurisdiction will be an open-air cemetery for the bandits of Martissant and Grand Ravine seeking refuge.”

Muscadin has reasons for his unflinching attitude. By all reports, he has a wide base of enthusiastic support from the population of Miragoâne. Following threats from Dorcé and Gilles, thousands of supporters flooded the streets in support of Muscadin. A week earlier, another large protest erupted after rumors that Muscadin would be transferred out of Miragoâne.

Muscadin’s popularity isn’t limited to Miragoâne. In late June 2023, he was gifted with an armored SUV, paid for by unnamed members of Haiti’s diaspora. The purchase was organized by journalist Theriel Thelus. Muscadin expressed his gratitude to the diaspora for their support and confidence.

The FJKL is fundamentally a political group with the facade of a human rights organization.

Popular support from inside and outside of Haiti seem to be irrelevant factors in Madistin’s analysis. In a Magik 9 interview, Madistin said Muscadin is “not the solution to growing insecurity in the country.” He accused Muscadin of being a “legal bandit,” whose actions “can be much more dangerous than those of armed bandits.”

Madistin then took a line of attack often employed against Cherizier, saying “Muscadin is accompanied by a group of armed civilians. We do not know how this group operates. Where do the weapons and ammunition used by Muscadin come from?” Should the allegation that Muscadin arms a vigilance brigade with guns confiscated from gangs or purchased in the U.S. be held against him?

Unsurprisingly, Pierre Espérance and the RNDDH have also criticized Muscadin, saying he is “accompanied by heavily armed civilians” in “possession, illegal weapons.” RNDDH denounced Muscadin because he “executes people, whom he presents as bandits, after subjecting them to hasty interrogation[s].” Espérance called Muscadin “a delinquent, member of the G9, working for the PHTK.” (Muscadin denied all the charges in a soon to be published Aug. 30 interview with Haïti Liberté and Redacted.)

Espérance is unconcerned with understanding the underlying reasons for Muscadin’s broad, popular support. The editors at Press Lakay, however, seem to have this understanding, stating in an editorial that Muscadin is “widely regarded as one of the most effective government commissioners in the Republic.” They argued that “any attempt to remove him from office would be risky,” pointing out that no actions were taken by Dorcé before he was dismissed from his post.

The FJKL is a political organization with the facade of a human rights group

Violence perpetrated by oligarch-backed armed gangs, which function as paramilitary groups, has fractured Haiti’s capital. The often-cited statistic that 80% of Port-au-Prince is controlled by gangs is misleading. A majority of Port-au-Prince is controlled by oligarch-backed gangs who often function as paramilitary groups. They oppose vigilance brigades and anti-crime groups like the FRG9, Bwa Kale, and local leaders like Muscadin.

Despite the battles that have raged between the FRG9 and the G-Pèp gangs over most of the past two years, three major truces have been negotiated in the past two months: 1) between Ti Bwa (Krisla) and Grand Ravine (Ti Lapli) with Village de Dieu (Izo); 2) between Brooklyn (Gabriel) in Cité Soleil and Iscard (Belekou) with Mathias (Boston); and 3) between Belair (Toto Alexandre and Kempes Sanon) and lower Delmas (Cherizier).

Cherizier has told Haïti Liberté that “these are not alliances, but peace accords.” Nonetheless, many media pundits are presenting the peace deals as a de facto alliance between the anti-crime FRG9 and the criminal gang federation G-Pèp.

The criminal gangs now extend well beyond Port-au-Prince into rural areas, threatening agriculture and local food supplies. Furthermore, insecurity and the threat of violence prevents what produce is grown from being transported. With more than a third of the population facing acute hunger, access to food is vital.

These armed gangs have destabilized Haiti, creating the justification for a foreign intervention which Henry requested to shore up his rule. This underlines Boulos’ support for G-Pep-associated gangs and his support for Ariel Henry. Boulos, like many Haitian oligarchs, wants a foreign military force to invade and occupy Haiti and protect his businesses.

Bwa Kale and the FRG9 are a result, in part, of the political class’ inability to organize a credible transitional government and force Henry out of office. They are, as Haïti Liberté director Berthony Dupont explained, “organic, autonomous, virtually spontaneous movements.” They are a response not only to the daily acts of depraved violence committed by oligarch-backed armed gangs but to the political void that has led to Henry’s uninterrupted reign as a U.S.-backed dictator.

This political leadership void has led to the rise of local leaders who defend their communities. Bwa Kale may be leaderless. There are, however, several local leaders who helped to organize vigilance brigades in their communities as part of the Bwa Kale movement.

All had come to a similar conclusion: Armed resistance to criminal gangs is necessary. The state has long abandoned its responsibility to eradicate gang violence and protect citizens from violence.

The PNH are unwilling or incapable of challenging criminal gangs. Consequently, dozens – perhaps more – of PNH officers have chosen to join or collaborate with FRG9 or their local vigilance brigade, recognizing the impotence of PNH leadership and the immediate need to rid their neighborhoods of criminal gangs.

Indeed, on Jun. 24, 2023 the Marien Patriotic Initiative (Initiative Patriote Marien – IPAM) published a statement calling for “the organization of vigilance brigades throughout the nation to protect the population and combat the gangs, murderers, kidnappers, and corrupt elements of the Ariel Henry regime.” IPAM is a collective of representatives of 33 local committees in the North and North-East regions of Haiti.

The FJKL is fundamentally a political group with the facade of a human rights organization. Whether it’s to Haitian oligarchs like Réginald Boulos or the U.S. government, the FJKL is committed to its benefactors and the class allegiances of its leadership.

The FJKL, like the RNDDH, is not a credible human rights organization.

Travis Ross is a teacher based in Montreal, Québec. He is also the co-editor of the Canada-Haiti Information Project at canada-haiti.ca . Travis has written for Haiti Liberté, Black Agenda Report, The CanadaFiles, TruthOut, and rabble.ca. He can be reached on Twitter.

[…] is a co-founder of FJKL, another discredited “human rights” group. A former politician, Madistin is the lawyer of Reginald Boulos, one of […]