This is part one of a three-part series by The Canada Files on Canadian imperialism in Haiti, versus the fight of the Haitian grassroots to free themselves from Western occupation.

On Apr. 2, a Haitian solidarity group named “Debout pour la dignité” (Stand up for Dignity) demonstrated in front of Prime-Minister Trudeau’s office in Montreal.

Their main demand is that Canada intervene in Haiti. The organization’s President, Wilner Cayo, spoke to the 200 demonstrators – all members of the Haitian diaspora. According to a Journal de Montreal report, he told the demonstrators that they want a “serious commitment” from the Canadian government” and that “Canada can make a difference.”

Joseph Flaubert Duclair, a member of Debout pour la Dignité told a Journal de Montréal reporter “we do not want a military invasion, but an operational force that intervenes on an ad hoc basis.” Duclair believes “Canada must do that, we don’t trust other countries.”

Debout pour la Dignité’s endorsement of a Canadian-led intervention in Haiti does not necessarily reflect the opinions of a majority in Canada’s Haitian diaspora. Only seven months ago, several leaders in the community told the Toronto Star’s Marisela Matador that they were against an intervention. Chantal Ismé, vice-president of community organization Maison d’Haïti and member of the Coalition haïtienne au Canada contre la dictature en Haïti, said most of Montreal’s Haitian community opposes foreign military intervention. Jean Ernest Pierre, owner and host of CPAM 1410 — a French-language radio station primarily serving the Haitian community in Montreal, echoed Ismé’s opposition saying “foreign military intervention and occupation have never helped Haiti and have only caused more harm.”

Reflecting the debate that is happening internationally, the Haitian diaspora have varied opinions on whether an foreign intervention into Haiti would help worsen the crisis there.

Understanding the framework for an intervention and occupation of Haiti

Following President Jovenel Moïse’s assassination on Jul. 7, 2021, interim Prime Minister Claude Joseph took power. Joseph’s successor, Ariel Henry, had already been appointed by Moïse, but was not yet sworn in at the time of the assassination. Washington and the CORE Group, of which Canada is a member, decided Dr. Ariel Henry ought to be the government’s head and installed him as Haiti’s de facto Prime Minister by a tweet on Jul. 17, 2021 that linked to a short statement by the CORE Group, which was dutifully posted by BINUH, the United Nations Office in Haiti.

The move demonstrated Haiti’s current status as a neo-colony, ruled by the American government and its CORE Group allies. Henry’s appointment by the neocolonial powers was in itself an intervention. It was also a holding action to allow Washington and the CORE group to organize a framework for intervention, while escalating the crisis of insecurity and poverty inside Haiti by way of Henry’s corruption and delaying tactics. Henry, who has no popular mandate, requested this intervention on Oct. 9, 2022. This request was supported by UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres.

The framework offered by Guterres in an Oct. 8, 2022, letter to the Security Council offers two options. One, a “special military force” whose aim would be to establish order in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince. Two, “support for the Haitian National Police (PNH)” in the form of “advisors”, equipment, training, weapons, and ammunition.

Efforts to simply invade and occupy Haiti were blocked at the Security Council by Russia and China. This followed concerted efforts by the Black Alliance for Peace and Haïti Liberté to lobby the governments of the two countries to block efforts by the U.S. and UN to send in a “Special Military Force.” These two organizations effectively relayed what the Haitian people have clearly expressed repeatedly: No to another foreign military intervention!

Canada’s Foreign Affairs Minister, Mélanie Joly, confirmed this in a comment made during an interview with RDI’s Daniel Thibeault on “Les Coulisses du Pouvoir.” Joly lamented that “the problem with the UN at the moment is that the Security Council is paralyzed because China and particularly Russia are blocking any form of work that can be done via the Council.” This highlighted Canada’s diplomatic support for the de facto leader’s request for intervention, despite Henry’s lack of support and a popular mandate.

In an Oct. 8, 2022 letter to the Security Council, Guterres explains that “the Haitian National Police is spread thinly.” According to Guterres, “some 13,000 officers are reportedly assigned to law enforcement activities” in Haiti. Importantly, “only a third are believed to be operational and undertaking public security functions at any given time.”

The number of PNH officers is believed to have dropped to somewhere between 9,000-10,000. The UN calculates that Haiti has a ratio of police officers to the population of 1.06 police officers per 1,000 inhabitants. This is nearly half of the UN’s suggested international ratio of 2.2 per 1,000.

It is understood that significant numbers of the officers are beholden to criminal gangs, work as personal security for corrupt politicians, or collaborate with vigilance brigades outside of the PNH’s command structure.

an “international force” of 3,000-5,000 would certainly lead to foreign officers having a significant and direct effect on daily life in Haiti.

Inadvertently outlining the risks of imperialist “support for the PNH” in the Dec. 2, 2022 Washington Post, former U.S. Ambassador to Haiti called for the Biden administration to send “2,000 armed law enforcers” to Haiti. To avoid the optics of thousands of armed American law enforcers landing in Haiti, she proposes that the U.S. “send in a couple of hundred at a time, over six months, with little fanfare.”

If “support for the PNH” becomes a slow but steady flow of foreign officers and military personnel into Haiti, foreign officers could easily match or outnumber the current PNH personnel, leading to a foreign occupation by a different name. This “support” can be framed as Haitian-led, as a handful of PNH officers would surely have a symbolic role in “anti-gang” police operations.

The reality is that an “international force” of 3,000-5,000 would certainly lead to foreign officers having a significant and direct effect on daily life in Haiti. “Support for the PNH” is simply foreign military intervention by another name.

Minister Joly casually confirmed how purported support for Haiti’s police can function as political doublespeak for occupation and oppression. “Canada is always a leader on the issue of Haiti,” she said, having “helped train police officers for years.” Joly is either unaware or forgetting that the police training she is referring to involved the RCMP being brought to Haiti to train PNH officers immediately after the 2004 coup d’état against democratically elected President Jean Bertrand Aristide. Aristide won over 90% of the popular vote in the 2000 elections, while thousands of Fanmi Lavalas (FL) candidates were also elected to various government posts. Most of them were also deposed during the coup.

An investigation by authors Nik Barry-Shaw and Dru Oja Jay revealed that the RCMP “provided training and vetting to the new Haitian National Police, which brought back many of the members of the feared national army that had been disbanded by Aristide.” This followed Canada’s active role in the coup that “plunged Haiti into violence and chaos from which it has yet to recover.”

Their investigation shows that RCMP-trained Haitian police were “frequently accompanied by U.S and Canadian soldiers and later United Nations forces” as they “embarked on a series of forays into the poorest neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince.” The PNH “killed innocent civilians, imprisoned political dissidents without charge, and drove key Aristide supporters into hiding or exile.”

When it became clear to Washington and the CORE Group in late 2022 that any attempt at a military intervention would be rejected by the Haitian people and blocked at the Security Council, Guterres’ second option for intervening in Haiti was accepted: “Supporting the PNH” through sales of arms, military equipment, military vehicles, training, and military and police “advisors”. As Joly explained, “the situation in Haiti has worsened and justifies Canada’s approach of strengthening the National Police of Haiti.”

In other words, the CORE Group’s support for PM Ariel Henry has caused insecurity and armed gang violence to grow to such a degree that a foreign intervention in some form seems inevitable.

Who will lead the occupation of Haiti?

Washington and the CORE Group have struggled to find a national leader willing to lead an intervention into Haiti, with only a handful of Caribbean and African nations offering to provide personnel or soldiers to support the PNH.

Efforts by the UN and Washington to find a nation willing to lead an armed intervention have so far failed. Even Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has, so far, refused the role. Instead, he tried to find a CARICOM leader to do so at the organization’s recent biannual leaders summit. He did get some nibbles from a handful of Caribbean leaders, among them Jamaican Prime MinisterAndrew Holness.

While willing to implicate himself in negotiations with Ariel Henry and various rival political and civil society groups, Holness couldn’t muster enough personnel and expertise to lead the intervention.

“six-month[s] is really a bait on the end of a hook to any country that might lead or contribute to a force there…. We’re likely talking five to 10, 15 years because we’re talking about nation-building.”

A few weeks later, U.S. President Joe Biden made his first visit to Canada. At the top of the agenda was Haiti. Trudeau again eschewed the call to lead an intervention into Haiti. After telling the media “Canada is elbows deep in terms of trying to help,” Trudeau promised another $100 million for the PNH and deployed two Kingston-class warships to “do reconnaissance” along Haiti’s coast. This followed Canada flying a military spy plane over Haiti, purportedly to do reconnaissance on gang activity. In addition, Canada has organized the sale of some armored vehicles to the PNH, with more on the way. Canadian Ambassador to Haiti Sébastien Carrière summed up the moves as “a significant military deployment.”

The initial delivery of armored vehicles was instrumental in breaking the blockade of the Varreaux fuel terminal in November of 2022.

Canadian military leaders have made it clear that they don’t have the resources to lead a mission into Haiti, making that scenario unlikely.

Furthermore, the timeline proposed for an intervention into Haiti is unrealistic, with retired Canadian General Tom Lawson making this blunt assessment to Matt Galloway on CBC Radio’s The Current: “…six-month[s] is really a bait on the end of a hook to any country that might lead or contribute to a force there. We are not talking six months. We’re not talking a couple of years. We’re likely talking five to 10, 15 years because we’re talking about nation-building. We’re not talking about establishing a safe and secure area for the government now to get to its tasks. We’re talking about a non-functioning government… And that’s in terms of – like we’ve seen in Afghanistan and Iraq – decades.”

Lawson’s observations underline how “support” for the PNH is simply providing cover for what would become another foreign occupation of Haiti.

Leading an occupation force into Haiti for a decade or more, with a population hostile to foreign troops, against gangs who are integrated into the geography and populations of Port-au-Prince, is likely unpalatable to Trudeau, who must be aware of this assessment.

Trudeau has no doubt been briefed about the 2004-2017 UN occupation force MINUSTAH. Its original mandate was for six months but was extended for over 12 years.

PM Trudeau has enthusiastically created a list of sanctioned Haitian politicians, so-called gang leaders and “business leaders.” This sanctions regime has been entirely performative. The few sanctioned Haitians who have any money or property in Canada have yet to see these sanctions enforced. More importantly, the vast majority of the targeted Haitian leaders and politicians have their money and investments in the United States.

Prior to the announcement of Henry’s December 21 Accord last year, it seemed that these sanctions were designed to get the fractured Haitian political class and business sector in line with Washington’s dictates. These sanctions have not threatened Henry’s power. While visiting the CARICOM biannual leaders meeting, he explained to VOA Kreyol that the sanctions have been “helpful” to him.

Ariel Henry’s main political rival: the Montana Accord coalition

Leaders of another Montreal-based Haiti solidarity group, Solidarite Quebec-Haiti (SQH) have recently thrown their support behind the Montana Accord. In an interview with Le Journal de Montreal, SQH leader Frantz André explained that “there must be a tactical force that provides on-site support, in coordination with the Montana group.” In a separate interview, SHQ’s Jean Saint-Vil also offered support for the Montana Accord, as did feminist activist Chantal Ismé.

SQH recently invited the Montana Accord’s proposed interim President, Fritz Alphonse Jean, to speak to Montreal’s Haitian community on Apr. 22, 2023 at the Haitian Cultural Association Perle Retrouvée.

The Montana Accord was born in August 2021. It was a result of a consultative process that began months before Moïse’s assassination and included Haitian civil society organizations, peasant’s organizations, political parties, and religious groups. The Accord includes a two-year transition plan centered on a provisional government that would oversee elections.

They purportedly had the support of somewhere between 400 and 650 groups and organizations from various sectors of Haitian society.

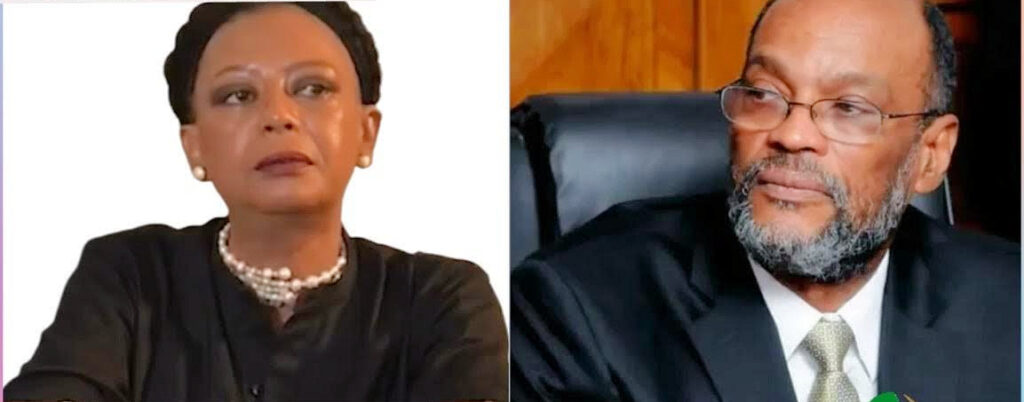

While Fritz Alphonse Jean is currently touring and speaking on behalf of the Montana Accord’s coalition, two other individuals tend to speak to the media on the coalition’s behalf: Magali Comeau Denis and Jacque Ted Saint Dic. Denis and Saint Dic have led the coalition since its early days prior to the announcement of the Montana Accord.

Comeau Denis and Saint Dic are now Henry’s political rivals, but this was not always the case. Following the American- and Canadian-backed 2004 coup, a “Council of Sages” was formed (sometimes referred to as the Council of the Wise). This council consisted of academics, cultural leaders, and politicians who supported the coup. Among this council’s “cultural leaders” tasked with selecting the post-coup government’s leaders was Ariel Henry.

They worked to consolidate the coup while the Latortue – Boniface dictatorship led a bloody campaign against FL members and supporters.

Magali Comeau Denis was one of the members of Haiti’s bourgeoisie whom the Council of Sages selected for the coup government. She was made “Minister of Information & Culture” in defacto Prime Minister Gérard Latortue’s regime.

This followed her active role in undermining the FL in the run up to the 2004 coup. Comeau Denis co-wrote a letter signed by dozens of Haiti’s elite, calling Aristide’s government a “tyrannical power.” The declaration claimed Aristide’s government was experiencing a “totalitarian drift” in addition to “incompetence and corruption.” The declaration claimed that by withdrawing support from the government, they were showing “unity” with fellow Haitians who had overwhelmingly voted for Aristide and the FL.

Comeau Denis eagerly participated in the anti-Lavalas campaign, similar to “human rights defender” Pierre Espérance, who targeted FL Prime Minister Yvon Neptune with manufactured accusations of orchestrating a massacre in La Scierie. Comeau Denis also levied accusations of murder against another FL leader as part of a campaign to criminalize the overwhelmingly popular party and suppress dissent.

In 2005, a journalist named Jaque Roches was found dead near a Port-au-Prince neighborhood where the FL remained popular. Comeau Denis accused an FL leader, the Rev. Gérard Jean-Juste, of orchestrating the murder. No evidence was offered.

This led to Jean-Juste being attacked in a Pétionville Church at Roches’ funeral by members of the Group of 184, a U.S.-backed “civil society” front. He survived the beating, only to be jailed for seven months by the regime. Upon his release, he was diagnosed with leukemia which he ultimately succumbed to a few years later in 2009.

Comeau Denis’ baseless allegations against Jean-Juste were part of a widespread propaganda campaign waged against FL, largely led by Pierre Espérance, the director of the National Human Rights Defense Network (RNDDH, formerly NCHR – Haiti).

Backed by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), NCHR-Haiti engaged in a “close working partnership with Latortue’s dictatorship.” According to Richard Sanders, a Global Fellow at the Wilson Center’s Canada Institute, NCHR-Haiti “became, in effect, an arm of the illegal ‘interim’ government.”

Brian Concannon, the director of the Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti (IJDH), described NCHR-Haiti as a “ferocious critic” of Aristide’s government and an “ally” of the illegal regime, formally called the Interim Government of Haiti (IGH).

According to Concannon, the Latortue regime “had an agreement with NCHR-Haiti to prosecute anyone the organization denounced.”

“People perceived to support Haiti’s constitutional government or Fanmi Lavalas, the political party of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, [were] systematically persecuted from late February through the present. In many cases, the de facto government of Prime Minister Gérard Latortue is directly responsible for the persecution,” Concannon explains. NCHR-Haiti “became increasingly politicized and, in the wake of the 2004 coup d’état, it cooperated with the IGH in persecuting Lavalas activists. The persecution became so flagrant that NCHR-Haiti’s former parent organization, New York-based NCHR, publicly repudiated the Haitian group and asked it to change its name.”

It is no surprise then, that Pierre Espérance, who continues to occupy the position of RNDDH’s director, is also a supporter of the Montana Accord.

Comeau Denis’ commitment to democracy and the Haitian constitution is not credible. She represents a sector of the Haitian bourgeoisie opposes PHTK rule but is in no way committed to democracy or Haitian sovereignty. Expecting a transitional government with Comeau Denis in a leadership role to rebuild a state, democracy, and maintain Haitian sovereignty, when she spent years destroying all three, strains credulity.

Rebuild a bourgeoisie or solidarity with the masses?

Ted Jacques Saint Dic, an economist by training, is one of the main spokespersons for the Montana Accord and, like Comeau Denis, has led the coalition behind the Accord since the beginning.

In September 2022, Saint Dic explained his mission “to lay the foundations for the reconstruction of a national bourgeoisie.” This was to be achieved by pushing for “a global consensus within the private sector” in Haiti.

Saint Dic doesn’t hide where his priorities are as a leader of the Montana coalition.Speaking on “Panel Magik” on Aug. 31, 2022, Saint Dic argued that the “political consensus needs to be broadened” and recommended reaching out to private sector leaders. “A united block of private sector leaders will have more political and social influence to find a solution to the crisis.”

What followed on Dec. 8, 2022 was a statement from the business community in Port-au-Prince promising to “cooperate with a consensus transitional administration to develop and present a political, humanitarian, and economic roadmap towards a new Haiti.”

The statement was signed by many business leaders and oligarchs based in Port-au-Prince, including, Laurent Saint-Cyr, representing the Western Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Jean-Philippe Boisson, representing the American Chamber of Commerce of Haiti, Michelle Mourra, representing the Haitian-Canadian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Fritz Mevs, representing Association of Ports of Haiti, Eddy Deeb, the son of Haitian oligarch Reynold Deeb, and Reuven Bigio, son of Gilbert Bigio, a Haitian oligarch who is also the richest man in the Caribbean.

This seemed to indicate that Haiti’s oligarchs were siding with the Montana Accord. Following Ariel Henry’s announcement of a renewed accord and coalition on Dec. 21, 2022 (hence named the “December 21” Accord or “Karibe Accord” after the hotel where the announcement was made), a collective of Chambers of Commerce outside of Port-au-Prince seemed to understand this wasn’t the case. They published a statement on Dec. 30, 2022 refusing to support Henry’s new Accord. The statement also denounced what they deemed a “centralized” and “criminal economy” which “the vast majority of politicians and their beneficiaries in the Port-au-Prince business sector – the true kingmakers – have nurtured and strengthened for decades.”

In February 2023, Laurent Saint-Cyr was selected by Ariel Henry to represent the business community on his High Transitional Council (HCT), indicating that Haiti’s ruling business elite – Haiti’s oligarchs – continue to support Henry.

During the 16 month period between the birth of the Montana Accord and that of Henry’s December 21 Accord, Saint Dic was focused on appealing to Washington for legitimacy. In a Sep. 7, 2022 article for Just Security, Saint-Dic argued that “U.S. officials should do everything in their power to seize this fragile opportunity to support and create space for Haitians engaged in an extraordinary effort to rebuild democracy.”

Saint Dic said that the U.S. has a “powerful and important role in helping get democracy back on track in Haiti.” Seemingly requesting a military intervention on behalf of the Montana group, he stated that: the “United States should use creative and aggressive tactics to intercept criminal activity in Haiti.”

These statements reveal Montana’s strategy for attaining power in Haiti: appealing to Washington for legitimacy and control of a transitional government. Comeau Denis and other Montana representatives met over, and over again with U.S. diplomats and government officials. Every step of the way they were told to negotiate with Henry and to “broaden the consensus.”

They got nowhere. The impulse to appeal to Washington for legitimacy as a path to install a Montana-led transitional government eroded their support inside Haiti.

Saint Dic’s focus on getting support from Haiti’s oligarchs while appealing to the Biden administration is a sign of what Haitians can expect from an interim government led by Montana: a devotion to neoliberal policies and U.S. imperial domination, while offering occasional nods to the Haitian Constitution.

Considering Saint Dic’s enthusiasm for collaborating with Haiti’s oligarchs, it is unclear exactly why support shifted so quickly back to Ariel Henry after announcing the December 21 Accord and the HCT. Upon its announcement, Washington showed renewed enthusiasm for Henry and his HCT, while continuing to call for a “broadening of the consensus.”

The loss of support clearly surprised Montana’s leadership.

According to Alterpresse, Saint Dic responded to Washington’s renewed support for Henry by saying Haitians must have the sovereignty to choose their own leader, “not the white people who will name them or decide when they should leave by means of a tweet.” Saint Dic was referring to the tweet by BINUH on behalf of the CORE group that installed Henry as Prime Minister.

He also disingenuously stated in the interview that Montana is “an opposition force in relation to international power, in relation to American power.”

This reversal in rhetoric would have been significant in 2021, before the coalition behind the Accord began to unravel. Considering the circumstances, however, it appears to be little more than a burst of frustration from a leader who spent 18 months appealing to Washington with nothing to show for it.

(Part 2)

An earlier version of this article was first published by The Canada Files. Travis Ross is a teacher based in Montreal, Québec. He is also the co-editor of the Canada-Haiti Information Project at canada-haiti.ca . Travis has written for Haiti Liberté, Black Agenda Report, TruthOut, and rabble.ca. He can be reached on Twitter.

[…] the “January 30th Agreement” – are opposed to the MSS with Henry in power and insist that a transitional government must be put in place before the MSS enters […]