The international press and some observers have trumpeted that Haiti’s Oct. 25 elections were a success. However, most Haitians would probably disagree, because they did not vote.

The international press and some observers have trumpeted that Haiti’s Oct. 25 elections were a success. However, most Haitians would probably disagree, because they did not vote.

In a random survey of the results at 76 voting bureaus in seven different voting centers around Port-au-Prince, Haïti Liberté found that only 14.7% of voters came to the polls. There were also clear indications of fraudulent voter tallies.

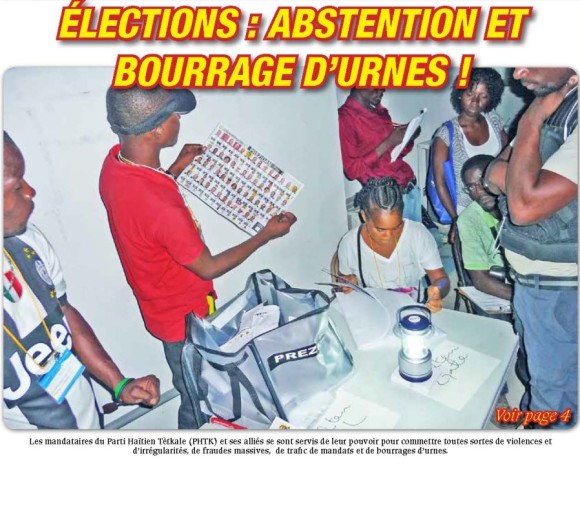

Voting centers had from dozens to hundreds of representatives from Haiti’s 128 registered political parties milling about and often squabbling with voting bureau personnel. Known as mandataires, these mostly paid representatives outnumbered voters at most centers.

It is true that there appears to have been less violence than occurred during the Aug. 9 first round of legislative contests, which were marred by mayhem, blatant intimidation, and fraud. But the level of violence during a vote cannot be the sole or even principal criteria for its success. Participation, calm, order, and transparency are equally important, and these were all lacking.

Haiti’s highly contested Provisional Electoral Council (CEP) says that the Aug. 9 election had only an 18% turnout, with only 6% in Port-au-Prince. Some observers say the true national turnout was much lower, closer to 5%.

The Oct. 25 election consisted of the legislative run-off, plus the first round for 54 presidential candidates and some 41,000 municipal races, mainly for 142 mayoral seats. Therefore, with the stakes much higher, why did turnout remain relatively low?

After the violence of Aug. 9 and during the days leading up to Oct. 25 (such as the killing of over 20 people in Cité Soleil the weekend before), many voters were afraid to venture out and vote.

Furthermore, many sectors of Haitian society, like the party Dessalines Coordination (KOD), boycotted the elections because they feel they are rigged and cannot be free, fair, and sovereign election with President Michel Martelly in power and Haiti under military occupation by 5,000 troops of the UN Mission to Stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH).

“There is the question of moral violence,” said Oxygène David of the popular organization Movement for Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity Among Haitians (MOLEGHAF). “The Haitian people’s democracy and sovereignty are being trampled by foreign imperialists who have taken over our electoral process, putting in whomever they please. This is maybe less visible to some than the killing which involves blood, but it is just as terrible.”

Long-time Haitian democracy activist Patrick Elie also did not vote, calling the elections “a comedy.”

“The elections in Haiti are becoming just like those in the U.S.,” he told Haïti Liberté. “It is money that decides the election, not the people.”

But perhaps the largest factor in voter disenfranchisement are the U.S.-inspired restrictions on how Haitians can vote. In the U.S., tens of thousands of poor and working-class voters, many of them black and Latino, are barred from voting rolls by restrictions against felons. Something similar is done in Haiti.

Haiti’s working poor are mobile, constantly on the move looking for work from town to town. Many are also small merchants and hawkers, who must travel great distances to sell their wares.

For instance, a metal worker named Peterson from Aux Cayes, interviewed by Haïti Liberté, found himself in Port-au-Prince putting iron grills on a house around election day, so he could not travel home to vote.

“I hope I get to vote in the run-off,” he said.

Multiply this situation by hundreds of thousands, and one starts to get the picture.

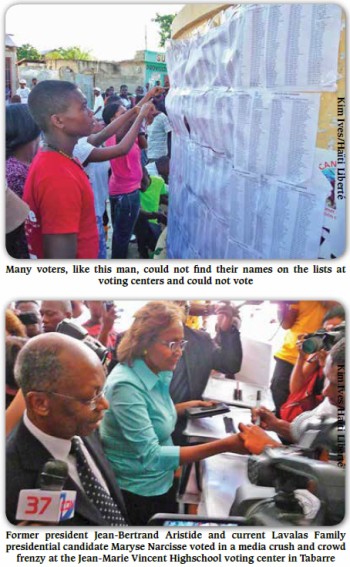

“Voting was much easier and logical in the historic 1990 election which brought Jean-Bertrand Aristide to power for the first time,” explained KOD leader Henriot Dorcent. “In that election, which was organized by Haitians without international direction like today, one registered to vote a month or two before the election, and then you went to the same place to vote. There was huge participation. Now you can only vote in the town where you got your electoral card. Then you go to these confusing, crowded voting centers with dozens of voting bureaus. Many people cannot get home to vote, many cannot travel the distance or navigate their way to the correct voting center, and many cannot find their names on the huge lists outside the voting centers.”

Despite their supposed success, the Oct. 25 elections had many confrontations and irregularities. So far, two days after the polling, the police have reported making 234 arrests, and voting centers and election materials were destroyed.

In the northern town of Au Borgne, elections were cancelled even before they began because unidentified vandals destroyed voting materials.

In Poirier, a locality of St. Marc, voting operations was also suspended following an altercation between two individuals and a police officer.

In Cap Haïtien, the Dessalines Children party of former Sen. Moïse Jean-Charles found a box of uncounted, discarded ballots for their candidate, which were taken to the city’s courthouse. The party alleges that the government’s party tried to destroy the ballots.

There was also trouble in Jacmel and the Artibonite Valley, where there were early arrests. Among the irregularities observers noted, some voters refused to allow poll-workers to apply indelible ink on their thumb, mandataires would not respect the electoral law and had shouting matches with CEP officials, some mandataires voted several times, some polling station workers themselves did not understand or apply the CEP’s instructions regarding accreditation credentials of mandataires and the rotation process, and thousands of voters could not find their names on the electoral lists.

In Petit Goâve, there was conflict between the partisans of two candidates for deputy: Jacques Stevenson Thimoléon of Martelly’s Bald Headed Haitian Party (PHTK) and Germain Fils Alexandre of former president René Préval’s Vérité platform. Heavy gunfire was heard around 10 a.m. near the voting center at the National School of Brothers, where a crowd accosted Thimoléon as he went to vote. Tensions then grew when Thimoléon spent too long in the polling station, according to some voters who were waiting in line. Then Thimoléon partisans are reported to have fired on the crowd, sparking panic. Earlier that morning, there had been disturbances in three localities of the 7th communal section of Petit Goâve: Vialet, Marose, and Delates. The Haitian National Police (PNH), which, unlike Aug. 9, were quick to intervene in cases of fraud or disorder, arrested about 30 people in Petit Goâve alone. They jailed for the day armed Thimoléon supporters trying to take material from polling stations.

In the capital’s northern suburb of Tabarre, police arrested two PHTK mandataires at the National School of Tabarre voting center at Tabarre 27. At the Jean-Marie Vincent Highschool voting center also in Tabarre, where former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide and Lavalas Family (FL) presidential candidate Maryse Narcisse voted together amidst a media crush and crowd frenzy, the police arrested Joris Duroselin, who took four ballots from voting bureau (BV) #49 and then returned to try to stuff the ballot box. The BV President and observers called the police to arrest him, drawing a huge crowd. He wore a pink plastic bracelet, a sign of support for President Martelly.

In Delmas, at the Father Froisset Mixed Institution voting center, police arrested a man with fake party representation credentials. Also, 100 voters were unable to find their names on the electoral roll at the National School of Beudot voting center.

In Cité Soleil, at the St. Anne’s School voting center, police arrested a man wearing a T-shirt identifying him as an election observer and equipped with several party mandates. The elections were disrupted on Aug. 9 at St. Anne’s, so security was reinforced by heavily armed officers from the PNH’s Corps for Intervention and Maintenance of Order (CIMO).

Also in Cité Soleil, some voters were denied entry to the voting center at the St. Vincent of Paul School Cultural Center, which caused great tension between them and the PNH.

“We had a difficult time this morning,” one policeman told Haïti Liberté in a crowded St. Vincent of Paul voting bureau in the early afternoon. “Things were getting out of hand but now have settled down.”

From Haïti Liberté’s random sampling in Port-au-Prince, it seems that four presidential candidates are in the lead of the reduced polling: 1) engineer Jude Célestin, Préval’s candidate for the Unity (Inite) platform in 2010, whom Washington pushed out of the run-off, overruling Haiti’s CEP, in favor of Martelly. 2) Banana exporter Jovenel Moïse, known as “nèg banann,” the candidate of Martelly’s party, whose campaign has had the most and largest billboards and posters around the country. 3) Maryse Narcisse, the Aristide-endorsed candidate of the Lavalas Family party. 4) Former outspoken senator Moïse Jean-Charles of the Dessalines Children, a break-off from the Lavalas Family.

Some voting bureaus’ tally sheets suggested fraud. For example, among the 56 BVs at the Elie Dubois National School voting center, the average participation was 12.3%, that is 56 people of the 470 that could vote. However, at voting bureaus #3 and #40, the tally sheets () reported that some 30.2% (142) and 27.9% (131) of the electors cast ballots respectively. One candidate received 82 votes at the first voting bureau and 40 votes at the second, while the four leading candidates generally received only between 7 to 19 votes at every neighboring voting bureau, with rarely more than a 5 point difference between them.