Haiti’s Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake – a decade ago this week — was one of history’s great natural disasters. However, it was not as great as the world’s large humanitarian relief organizations and their allied media outlets would have us believe. It became a money-making tragedy.

That is the message of the following article by Haiti-based anthropologist Tim Schwartz. First published on his blog in May 2019, this piece is adapted from a chapter in his 2017 book “The Great Haiti Humanitarian Aid Swindle.” It has been abridged for Haïti Liberté.

Dr. Schwartz is probably best-known for scientifically estimating the quake’s death toll: 46,000 to 85,000, not the 300,000 often bandied about.

This article examines the charades surrounding the internally displaced persons (IDP) tent camps, which became the symbol of the quake’s aftermath.

Kim Ives

In the wake of the Jan. 12, 2010 Haiti earthquake, the world witnessed the growth of what would become the largest refugee crisis on the planet. If we can believe claims from the United Nations, the U.S., and the EU governments, and the humanitarian aid agencies that together received some $3 billion in donations from individual and corporate donors, the displaced population in Port-au-Prince reached 2.3 million people, 1.5 million of whom were in living in temporary camps located in the vicinity of metropolitan Port-au-Prince, the capital of Haiti.

That was six times the next largest complex of refugee camps in the world at the time, the 239,500 people in Dadaab complex of refugee camps in Kenya who had fled civil war in Somalia. But in the case of Haiti, people were not fleeing violence, they were supposedly displaced by the earthquake. Supposedly. The fact is that those organizations giving us the data could not be believed… The crisis was largely the creation of those very organization collecting the money on behalf of the “earthquake survivors.”

Specifically, the Haiti earthquake refugee crisis was the result of three forces:

- First and foremost, the radical exaggerations and hype from United Nations, representatives of the U.S. and EU and NGOs bent on collecting as much donated money as they possible could.

- Attempts on the part of impoverished Haitians to partake in the donations, aid they knew very well had been given in their names, as they had access to reports on the radio and to information from family in the U.S., Canada, and elsewhere.

- The attempts by many of those impoverished Haitians to use the earthquake crisis as an opportunity to appropriate land legally in the hands of elites, a process that has been common for the two centuries of Haitian history, but the opportunity for which has been intensified with the post-earthquake aid tsunami and presence of international aid agencies.

Being an Earthquake “Viktim”

“When they see us coming they run out with their sheets, and they throw up a tent.” It’s Jul. 9, [2010], seven months after the earthquake, and I am talking to Maria who is working in the camps.

Maria is middle class, fiftyish, from Honduras. I haven’t asked her for this information, she’s volunteering it. We are in a restaurant having dinner. My Foreign Service friend, Joseph, is with us, as well as another aid worker, a woman from Rwanda. I asked Maria about her job and she started telling me about the camps. “Many of these people, they have homes,” she says with a tone of exasperation. “In some areas we work they were not even affected by the earthquake.” World Vision, her employer, has assumed responsibility for 15 camps. She describes what happens after the aid workers arrive. [1]

“When we take over a camp or move people to places like we did on the border, every week there are 100 more people. They have their bed sheets over their rickety little wooden frames… No one is living there. But when they see a World Vision vehicle, they come running.”

Maria is not telling me anything I don’t already know. But what is surprising to me is that it’s so obvious even to her. She speaks no Kreyòl and no French. She has no special insight that would help her see or understand anything about Haiti that anyone else cannot see and understand. She has not been out living in camps or doing hard core research to get this information. She just visits camps as part of her job. Yet, that very day Nigel Fisher, UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Haiti, had declared in the United Nations official ‘6-Months After Report’, “a staggering 2.3 million internally displaced persons,” of which 1.5 million were living in camps. That would have been 46% of all 3.375 million people in the entire strike zone; 58% of those living in urban areas. But Fisher didn’t say anything about the fake tents. Maria doesn’t understand why. “It is,” she’s telling us, “obvious.” And it bothers her. “It is like no one cares whether the recipients need aid or not.”

Lest Maria and I be misunderstood, let me step back for a moment and explain something. Maria was not talking about the tents and makeshift shelters where people moved all the possessions they could scavenge from their collapsed home. There were many of those shelters. Tens of thousands.

Maria was describing another kind of shelter and camp; the kind that, if any aid worker or journalist had done the math or a survey — and I’m getting ready to recount that we did both — they would have known there were even more of. And they would have known that most were bogus. These shelters had no clothes hanging to dry on a line, no charcoal fires, no pots and pans, no people sleeping in them. If you poked your head inside one of them, you would more than likely have found them empty, and you would often have found a surface on which no one possibly could or would sleep: rocks on the floor, tree roots sticking up.

These were what my Foreign Service pal Joseph called “aid bait.” They sprang up throughout Port-au-Prince and in a 40-mile radius around the metropolitan area and even in some towns and cities as far as 100 miles away from the earthquake strike zone.

Haitian Vilmond Joegodson, who grew up in Cité Soleil, one of Port-au-Prince’s poorest neighborhoods, and who moved into several of the camps, described the process:

All that was needed was eight long sturdy branches and some sheets to hang from them to represent walls… The NGOs decided to visit them and to distribute whatever tents or tarps they still had. To qualify for those donations, or other aid, Haitians needed to have a place etched out in one of the camps and to have demonstrated some proof of residence.

Everyone kept their ears open to find out where the NGOs were distributing the tents most generously. The objective was to go to that camp and demonstrate a presence. Then wait. Sometimes people squatted in a number of camps at the same time in order to cover all their bases. [2]

Absurdity of the Numbers

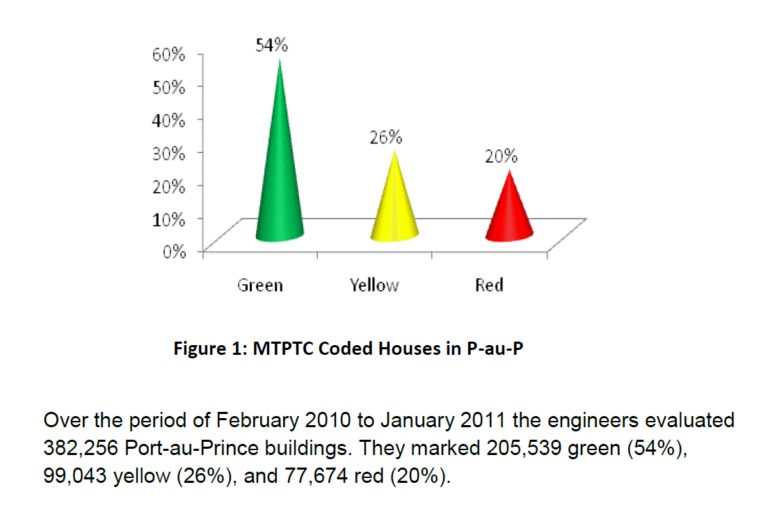

You did not have to take my or Maria’s or even Joegodson’s word for the fact that many of those people in the camps were not really “viktim” of the earthquake. By the time that Nigel Fisher was declaring 1.5 million people in 1,555 camps, it was already reasonably certain that it was not 70% of the buildings in Port-au-Prince that had collapsed. It was 7% of the buildings. Another 13% were damaged such that demolition of the structure was recommended. That meant that a total of 20% of the buildings were unfit for habitation. And that meant that no more than 29% of the population should have been what the authorities were calling IDPs (internally displaced persons); at least, not if the criteria for being an IDP was that the home you were living in was destroyed.

If we extend the definition of an unfit home to include the yellow houses — the 26% of houses that were damaged but still reparable — there could logically have been no more than 46% of the population homeless, which is closer to the 68% of the population the UN reported as IDPs. The remainder of the houses were “green” which meant that they had no significant structural damage. But there were still big problems with the calculations. [3]

For those of us who lived in Port-au-Prince, we knew that most homes abandoned after the earthquake had been reoccupied within a couple of months of the disaster. And once again, you didn’t have to take our word for it. In the BARR Survey, we found that at the height of the exodus exactly 68% of residents in the earthquake impacted region left their home. That extrapolates to 2,040,000 people. But not all of those people went to camps. The UN estimated that 24% of the IDP population had gone to the countryside or were living in the homes of family or friends. BARR, UN’s OCHA, and the University of Columbia working with Sweden’s Karolinska Institute all found similar figures. Others were living in the street in front of their home.

For those of us who lived in Port-au-Prince, we knew that most homes abandoned after the earthquake had been reoccupied within a couple of months of the disaster. And once again, you didn’t have to take our word for it. In the BARR Survey, we found that at the height of the exodus exactly 68% of residents in the earthquake impacted region left their home. That extrapolates to 2,040,000 people. But not all of those people went to camps. The UN estimated that 24% of the IDP population had gone to the countryside or were living in the homes of family or friends. BARR, UN’s OCHA, and the University of Columbia working with Sweden’s Karolinska Institute all found similar figures. Others were living in the street in front of their home.

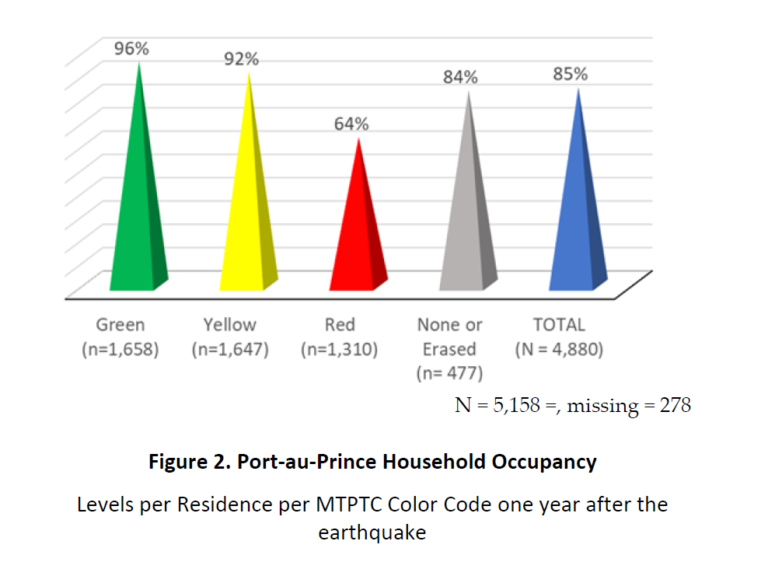

In short, less than half of the IDPs went to camps; or more precisely, 900,000 people or 30% of the total population in the earthquake strike area went to the camps. But they began returning home within weeks of the earthquake. BARR tells us that 70% of people who had left their homes had returned to them by July 2010, when IOM [the International Organization for Migration] — that organization that the UN had designated as responsible for coordinating aid to camps in Haiti — was estimating there were 1.5 million people in the camps. At the one-year anniversary of the earthquake, when IOM estimated there were still 1 million people in camps, BARR tells us that 85% of those people who had left their homes were back in them. Even the 78,000 red-tagged-structure residences — those recommended for demolition — had a re-occupancy rate of 64%. For the 100,000 yellow-tagged residences — those damaged but reparable — the reoccupation rate was 92%; and for the 206,000 green-tagged structures — those that were undamaged — the re-occupancy rate was 96% (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

In short, less than half of the IDPs went to camps; or more precisely, 900,000 people or 30% of the total population in the earthquake strike area went to the camps. But they began returning home within weeks of the earthquake. BARR tells us that 70% of people who had left their homes had returned to them by July 2010, when IOM [the International Organization for Migration] — that organization that the UN had designated as responsible for coordinating aid to camps in Haiti — was estimating there were 1.5 million people in the camps. At the one-year anniversary of the earthquake, when IOM estimated there were still 1 million people in camps, BARR tells us that 85% of those people who had left their homes were back in them. Even the 78,000 red-tagged-structure residences — those recommended for demolition — had a re-occupancy rate of 64%. For the 100,000 yellow-tagged residences — those damaged but reparable — the reoccupation rate was 92%; and for the 206,000 green-tagged structures — those that were undamaged — the re-occupancy rate was 96% (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

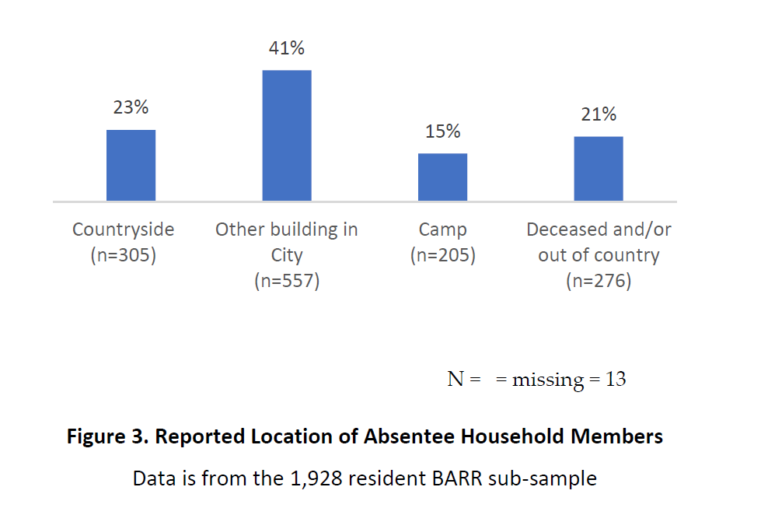

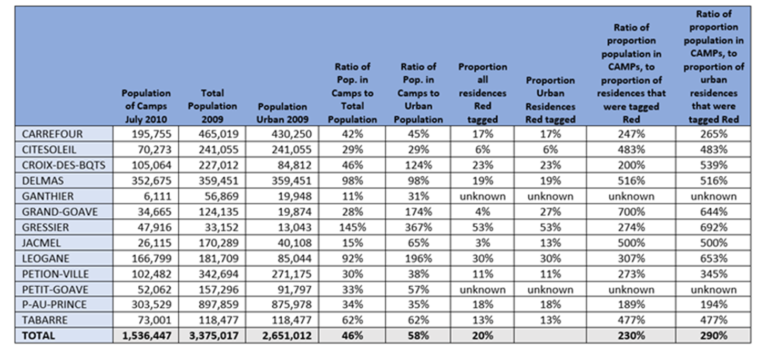

Even if we were to include all the missing variables from the survey for reasons of non-reporting, we had solid data that at least 80% of people had re-occupied their homes one year after the earthquake. So once again, even if we’re liberal about the estimate, at the one-year earthquake anniversary no more than 20% of the population —about 675,000 people — should have been IDPs. That’s not people in the camps; that’s IDPs, meaning people who had not returned home. Based on reports in the BARR survey, of the 1,356 residences with absentee members, only 15% of those absentees were still located in camps (see Figure 3). This meant that of people from the earthquake impacted area, no more than 101,250, people who had been living in Port-au-Prince at the time of the earthquake were living in camps. Yet, the camp counts from the government and IOM found – or claimed – that there were still 1 million people in camps. Some of these extra people could and certainly were from outside the earthquake strike area living in camps, but the point is that something was definitively out of whack with reality. In some Port-au-Prince area counties, there were more people claiming to live in camps than the total number of people living in the county when the earthquake hit. [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9]

Even if we were to include all the missing variables from the survey for reasons of non-reporting, we had solid data that at least 80% of people had re-occupied their homes one year after the earthquake. So once again, even if we’re liberal about the estimate, at the one-year earthquake anniversary no more than 20% of the population —about 675,000 people — should have been IDPs. That’s not people in the camps; that’s IDPs, meaning people who had not returned home. Based on reports in the BARR survey, of the 1,356 residences with absentee members, only 15% of those absentees were still located in camps (see Figure 3). This meant that of people from the earthquake impacted area, no more than 101,250, people who had been living in Port-au-Prince at the time of the earthquake were living in camps. Yet, the camp counts from the government and IOM found – or claimed – that there were still 1 million people in camps. Some of these extra people could and certainly were from outside the earthquake strike area living in camps, but the point is that something was definitively out of whack with reality. In some Port-au-Prince area counties, there were more people claiming to live in camps than the total number of people living in the county when the earthquake hit. [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9]

Even Without the Numbers, They Knew

So those are the numbers. But the fact is that you didn’t even need the numbers. Everyone in any position of authority knew damn well that many people in the camps were only pretending to be IDPs. One of the first things USAID/OFDA [Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance] representatives told me when they briefed me for the BARR Survey was about the massive opportunism. The two women who briefed me, one from OFDA and one a consultant for the U.S. State Department, told me point blank, “We know that a lot of the tents are empty.”

They explained that SOUTHCOM (U.S. Southern Command) had been into the camps at night with infrared goggles and many of the tents were empty. “And,” the woman working with OFDA added, “we know that people in the camps are splitting families to occupy multiple tents so that they can get more aid.” So when UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Haiti, Nigel Fisher, announced to the world that there were 1.5 million people living in camps, there is simply no way that he himself could have believed the figure was remotely accurate. Once again the leaders of the humanitarian aid effort were flat out lying to us. [10]

(Part 2)

Notes

[1] “I don’t think they are really hungry.” Maria, the woman from Honduras also said, and she was not being insensitive. She understands that they are poor. She has already said, “they are so poor, they are desperate.” But she’s perplexed, “It’s like this is what they do, it’s like some kind of opportunity.”

[2] For quotes and accounts from Joegodson see, Deralcine, Vilmond Joegodson and Paul Jackson. 2015. Rocks in the Water, Rocks in the Sun: A Memoir from the Heart of Haiti (Our Lives: Diary, Memoir, and Letters Series) Paperback – April 23, 2015.

[3] For the building structural evaluations see, Miyamoto, H. Kit Ph.D., S.E (Seismic Engineer)., and Amir Gilani, Ph.D., S.E 2011 Haiti Earthquake Structural Debris Assessment Based on MTPTC Damage and USAID Repair Assessments. Miyamoto International

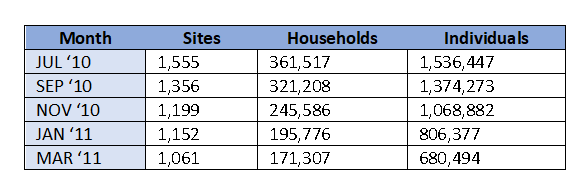

[4] Data from IOM on home returns by month and year for 2010 and 2011:

[5] Most of the controversy over the BARR Survey centered on the death count. But we also estimated that only 1 of every 20 people in the camps came from earthquake impacted homes. Indeed, that might have been the biggest reason that USAID in Washington had reacted so strongly to the release of the report. As Professor Mark Schuller would unwittingly admit when attacking it, “a red herring.” What was really at issue was the legitimacy of the camps. Schuller would write:

… the attention deflected away from this discussion of the “illegitimate” IDPs, was an insidious outcome. With the public debate focusing on what to most Haitian people I know consider a red herring—with nothing to be done about the dead, no one ultimately responsible for their deaths – the inflammatory and controversial allegations about living IDPs, whose rights were actively being challenged by a range of actors, became tacitly accepted by the lack of scrutiny.

….

To the oft-repeated quote – amplified and justified by the Schwartz report [the BARR] – of people suddenly appearing in unused tents whenever a distribution was made, my eight research teams spent five weeks in the same camp and noticed a constant level of comings and goings, economic activity, and social life. In other words, they were all “real” camps.

(see, Schuller, Mark. 2011. “Smoke and Mirrors: Deflecting Attention Away From Failure in Haiti’s IDP Camps,” Huffington Post. December. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/mark-schuller/haiti-idp-housing_b_1155996.html )

[6] If we had listened to the government death count estimates and the camp estimates, that would have meant this: in July 2010 there would have had 1.5 million people in Camps, 800,000 more in rural areas or homes of others, and another 316,000 dead, for a total of 2.616 million people out of a population of 3.4 million, 76% of the population. And yet the survey indicated that as of July, 75% were back home. So if 75% were back home, and 12% were dead, we had an extra 2 million people.

[7] Lest anything be misunderstood in the main text, here is what we found out from the BARR Survey and corroborated from data from Columbia University and Karolinska Institute, was that immediately following the earthquake, 68% of residents of greater Port-au-Prince left their homes. Of that we know that in the weeks immediately following the earthquake:

9% went to the homes of others

21% moved into the yard or the street in front of their home

26% (between 465,246 and 584,754) people left Port-au-Prince and went to stay with family in the countryside

44% concentrated in the spontaneous tent cities that appeared throughout the metropolitan areas.

What this means in terms of numbers is that between 866,412 to 894,588 ( p<.01) people went to camps.

But by July—when IOM and most newspapers and the Haitian government were reporting 1.5 million people in camps—75% of those who left Port-au-Prince were back in the city. And from the BARR Survey we knew that 66% of all those who had left their homes were back in their residence or in some kind of shelter on the property. That includes people who reported having gone to camps.

Corroborating the BARR findings, Colombia University and Sweden’s Karolinska Institute—the same ones who would use cell phone data to estimate earthquake deaths—found almost exactly the same figures for the geographical movement. In their case, they used cellular phone data to track the movements of people. They could not tell how many people were in camps or if someone had moved back to their residence prior to the earthquake, but they could tell how many left Port-au-Prince for rural areas and they could tell when they came back to the city. What they concluded was that 570,000 people had fled the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area for the provinces. There was also data from the United Nation’s organization OCHA, which was coordinating the aid effort and had sent staff to the provinces to count the migrants. They counted 511,405. So the three major surveys on migration found the same pattern, between 465,246 and 584,754 people left Port-au-Prince in the month after the earthquake. Moreover, studies by the same institutions of estimated return to the city of those IDPs were also very similar.

For the Cell Phone data see:

Bengtsson, Linus, Xin Lu, Richard Garfield, Anna Thorson, Johan von Schreeb. 2010. “Internal Population Displacement in Haiti Preliminary analyses of movement patterns of Digicel mobile phones: 1 January to 11 March 2010,” May 14. Karolinska Institute, Center for Disaster Medicine, and Columbia University, Schools of Nursing and Public Health.

For the OCHA data on populations movement see: United Nations/OCHA. 2010. “Haiti Earthquake – Population Movements out of Port-au-Prince – 8 February 2010.”

http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/rwb.nsf/db900sid/MNIN82GQYS?OpenDocument&query=population percent20movement&emid=EQ-2010-000009-HTI. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

[8] Here are the specific numbers from the USAID/BARR Survey of 5,158 residences regarding how many people were in camps. One year after the earthquake, IOM was still claiming 1 million, 88 percent of Port-au-Prince residents were back home. Based on that figure, the estimated number of legitimate IDPs was no more than 375,031 people.

[9] Regarding the veracity of asking people in the BARR Survey about being in camps: This did not mean, of course, that a respondent didn’t have a tent in a camp. The point is that they were unlikely to tell us if they did. But by the same token, there was no apparent reason why they would have reported themselves living in the house or yard when they were really living in a camp. Indeed, the beauty of the BARR Survey was that we had approached the issue from the other direction. Rather than counting people in the camps and asking if they really lived in the tent or if they really didn’t have house, we had gone to the source, houses. And that’s what made the BARR Survey and estimating the number of real IDPs foolproof. Indeed, it might have been the only way to do it. No one would ever be able to get the information from the camps because those in the camps who had a home, or who were renters who had lost nothing but no longer wanted to pay rent (and who can blame them), or who were capitalizing on an opportunity to migrate from the rural areas to Port-au-Prince, were not about to tell surveyors that they were trying to game the NGOs. It would have defeated the whole purpose of being in the camp. But because we went to houses, people had no reason to say they were in camps. In fact, if they were also in a camp, they were not going to say so at risk of impugning themselves. And so by doing that, by determining who was home and asking about the whereabouts of everyone else who had been in the residence at the time of the earthquake, we were working from the other direction. We asked the residents in the sampled houses where they went after the earthquake and where they were at the time of the BARR. If we couldn’t find any residents—as in the house was destroyed—we did the next best thing, we asked the neighbors. That made it a powerful way to go about estimating the camp population. And just like the death toll there was good reason to believe we had over-estimated. We were drawing on people in the hardest hit areas of Port-au-Prince. And just like the death count, the aid executives and activists were incensed. Yet, as I keep trying to emphasize, none of this means that there were not desperate people in Port-au-Prince. There were. They have been for a long time. Long before the earthquake. I’ll get back to that.

[10] One more of so many clear declarations from significant sources deeply entrenched in the relief effort and who contradicted the official claims of 2.3 million legitimately displaced persons came from Kit Miyamota, the Japanese seismic engineer who oversaw the USAID/UN/Haitian government house assessment program Miyamota recounted to me that,

When we repair yellow houses [damaged homes], we get to know the owners and renters very well since we stay there for an average of three days. Our Haitian engineers know their living status. After we repair yellow houses, approximately 100% of people return for 24 hours a day. But about 90% of them keep the unoccupied tents in the IDP camps since they hope to receive services and money to remove them. (Personal Communication by E-mail, 2011, published in USAID/BARR 2011)