Hurricane Irma may have skirted it (causing major damage nonetheless), but it’s only a matter of time before another“natural” disaster devastates Haiti, which sits between two major earthquake faults and in the middle of the bowling alley down which the ever-warming Atlantic Ocean hurls its strengthening storms at North America’s East Coast.

Already Haiti has more non-governmental organizations (NGOs) than any other country on earth, but when the next disaster hits, they will again multiply like rabbits.

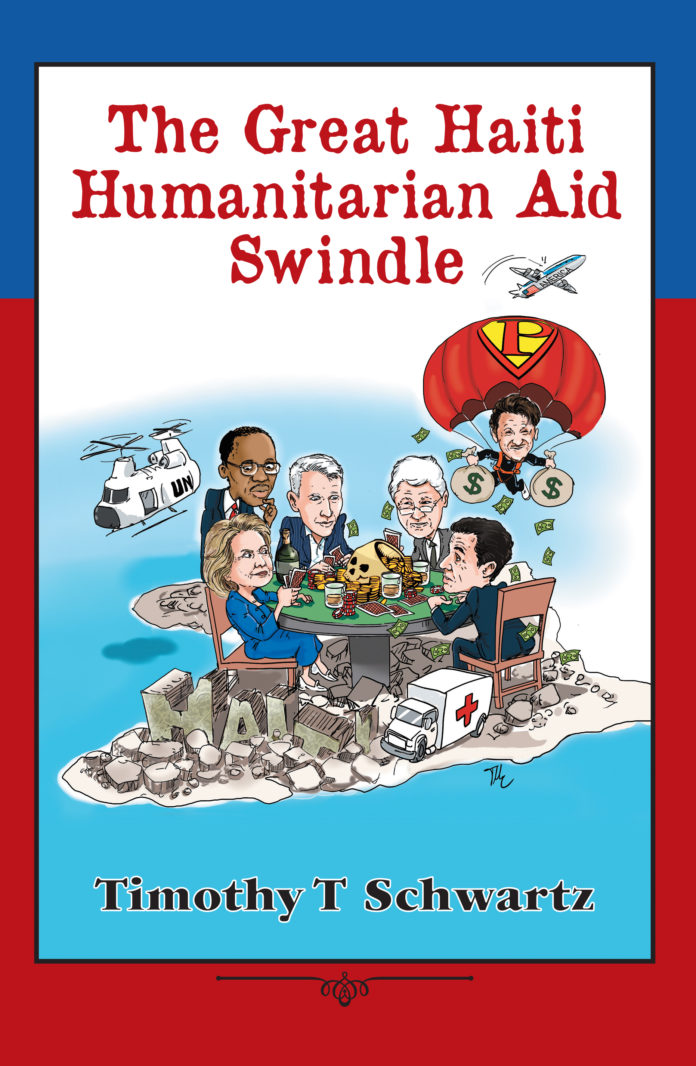

Dr. Timothy Schwartz has worked for many NGOs in Haiti over the past 27 years, and his new book – “The Great Haiti Humanitarian Aid Swindle” – begins with the most well-known recent disaster: the Jan. 12, 2010 7.0 magnitude earthquake, which struck just west of the capital, Port-au-Prince. This event provides the principal tableau for his merciless evisceration of “the world’s most respected humanitarian organizations,” assisted by “journalists from the world’s most esteemed news agencies,” which he argues “deceive and manipulate people overseas regarding what is really happening in Haiti,” the book’s jacket explains.

On hearing about the quake, Schwartz, an American with a Haitian wife and kids, immediately drove from the Dominican Republic with two friends to try to help. “Like so many foreigners who have lived and worked in Haiti, I am haunted by a sense of frustration and failure,” he writes. “An anthropologist and sometimes aid worker, I had spent much of the preceding 20 years watching the country sink ever deeper into misery and despair while I had done nothing tangible to help slow down the process.”

Such raw honesty and self-critique (which also laced his previous self-published but widely read book “Travesty in Haiti: A true account of Christian missions, orphanages, fraud, food aid and drug trafficking”) are what make Schwartz’s writing so compelling.

But the reader is also swept along by his sometimes entertaining, sometimes moving anecdotes and stories as well as a torrent of illuminating facts and figures, found on almost every one of “Swindle”’s 300 pages. Schwartz has exhaustively researched almost every assertion he makes so that the endnotes run for another 200 pages, and they are also fascinating reading.

“Swindle” goes a step further than “Travesty” in deeply plumbing the complex and contradictory dynamics between humanitarian, disaster, or development aid givers and recipients. This is best illustrated by his chapter on “orphans” where he writes that “I have never found an article that succinctly summed up the labyrinth of exploitation and conflict and confusion that swirled around the orphan crisis. But what we were seeing was a very specific mélange of interests and exploitation” between “those who want to adopt” and “the impoverished children themselves and – for the more than 80% of Haitian adoptees who have them – their parents.”

With this book, Schwartz fills this void by precisely “summing up the labyrinth” in a way that is clear, nonjudgmental, and yet compassionate. In addition to “orphans,” he also deconstructs myths around Haiti’s “rape epidemic” (“another massive delusion on the part of news outlets and humanitarian aid agencies in pursuit of readership and donations”) and the internally displaced persons (IDPs) who supposedly swelled to 2.3 million, with 1.5 million living in hundreds of tent camps (“Everyone in any position of authority knew damn well that many people in the camps were only pretending to be IDPs”).

Schwartz won his fame – or infamy, for some – in 2011 when he helped publish a Building Assessment and Rubble Removal (BARR) survey “involving 18 university educated surveyors, myself, and two other PhD’s.” Their job was “to estimate the number of people who had returned to their homes since the earthquake. To do that, I had to know how many people were killed.”

Until that time, the official Haitian government figure for the earthquake’s death toll was 316,000, a figure whose origin no Haitian official could explain. Using statistical methodology, Schwartz and his team found a very different result: “Based on the data, we estimated with a 99% probability, that the earthquake death toll was 46,190 to 84,961,” which, statistically speaking, “was like hitting the broad side of a barn with a softball at 30 feet.”

Rather than rejoicing that he’d proved that about 80% fewer people had actually died in the quake, government and humanitarian agency officials were furious with Schwartz, especially the U.S. State Department’s Agency for International Development (USAID), which had contracted him. “You tricked us!” one U.S. government official shouted at him. “No one authorized you to estimate the number of people killed.”

But Schwartz is a “numbers guy,” a retiring nerd (by his own account), who treats statistical accuracy with religious fervor, as he should. He has no ideological dog in the fight. If you fudge or fabricate figures, or even are sloppy in repeating or not verifying them (as many journalists and academics are), he is coming for you. He clearly treats the rise of the Lavalas governments as democratic and progressive, and the two coups (1991 and 2004) against President Jean-Bertrand Aristide (as well as Michel Martelly’s government) as reactionary, but he is not going to give you a pass simply because you are the former’s partisan. He devotes one chapter (“Politics of Data: The Pretender”) to criticizing University of Michigan researcher Athena Kolbe, who has been closely associated with Aristide over the years, particularly when she was a journalist known as Lynn Duff.

Sometimes, however, Schwartz displays a certain political agnosticism that looks a bit like blinders. When “popular politicians… sought to raise the minimum wage [of about $1 a day] and levy taxes” on the assembly industries of “Haitian factory owners and partners of multinationals [who] were, of course, among the wealthiest people in Haiti,” he explains “the struggle broke out into open violence and political turmoil” so that the “number of garment workers in Haiti went from 100,000 in 1990 to less than 20,000 in 1994.”

“I’m not taking sides here,” he then concludes. “I don’t care one way or another who was right or wrong; it’s not for me to decide.”

Despite such strained and questionable neutrality, Schwartz’s dogged pursuit of truth in portraying Haiti accurately is a revolutionary act. It is all the more commendable because he courageously bites the hand that feeds him in a manner that no other researcher of his caliber, engagement, and insider status has done.

And yet he is a conflicted whistleblower, at least with respect to the Haitians who try to game this corrupt humanitarian system. “Some, if not many, Haitians have disingenuously insinuated themselves into the aid pipeline, and … there is definitively something irksome about a movement veiled in exaggerations, untruths, and outright lies,” he writes.

“Whether we are talking about individuals who falsely claim to have been tortured or raped to get visas or … about parents who present their own children as orphans or child slaves, there is, then as now, a profound and defensible logic to what was happening across the entire spectrum of aid in Haiti, a logic underlying the emerging economies of deceit and falsehoods. With the U.S. neo-liberal policies, … many traditional economic opportunities for the poor in Haiti, such as production of agricultural exports, had disappeared. Faced with a dwindling economy, declining living standards, and massive amounts of aid provided from abroad but channeled through NGOs that define specific criteria to qualify as a victim – such as orphan, restavek, or rape survivor – those impoverished women who were lying and exaggerating were trying to survive and adapt to the emerging aid economy… It’s not enough to be poor… [or] to have had your government undermined and your economic livelihoods destroyed. You want a piece of the new pie? You’ve gotta be a victim, of some kind.”

“Swindle” nicely complements and reinforces Dady Chery’s 2015 “We Have Dared to Be Free,” particularly in explaining the absurdity of the humanitarian myth of “child slaves” or restaveks. This child domesticity institution is “one of the primary means of social mobility for poor rural Haitian children,” Schwartz notes. “In summary, the average restavek was, in terms of physical well-being, statistically better off than the average Haitian child living with his or her parents.”

The humanitarian sector “is the eighth largest economy in the world” and “is growing at an annual rate of 6 percent.” So it is timely that this book does a thorough and excellent job of outing everything from sacrosanct behemoths like UNICEF, CARE, and the Red Cross to smaller opportunist pop-up NGOs, most of whose directors “considered NGO’s above accountability,” despite that they “collude in corporate dumping, market takeovers, (…) tax evasion,… covert military operations, and even terrorism.”

Schwartz recognizes the difficulty of neutralizing these humanitarian agencies which have become “the executors of government plans that undermined the Haitian economy” through things like food and used clothes dumping, and massive aid injections to “institutions that were not part of the Haitian government” and therefore “turned Haitians away from solving their own problems.”

Schwartz proposes a central website to vet data, rate reports, and provide feedback, among other things. It sounds simple enough, but the devil is in the details and financing of such a site, not to mention the push-back from, inertia of, and sabotage by the humanitarian mafia. Already Schwartz has started to take a lot of heat, legal and otherwise, for his exposé of how “the humanitarian aid agencies and the international press that carries their message [have] demonized Haiti and the people who live there and turned it into a land of savages, rapists, satanic worshipers, and mud eaters.”

The hyperbolic portrayal of Haiti creates a kind of feedback loop. At the beginning of the book, Schwartz wonderfully relates his first-hand experience with U.S. earthquake first-responders and even soldiers who were terrified of the very people they were supposed to be helping. “Press reports of widespread violence stoked that fear,” but “it was almost completely untrue,” he writes.

Schwartz’s goal is best understood from the book’s dedication to “the millions of people who have donated money to help impoverished Haitians,… tens of thousands of rescue workers and sincere aid employees who have gone to Haiti to help,… the impoverished Haitians who are meant to benefit from aid, but the many, if not most, who do not benefit, and… future generations of Haitian children.” They all “deserve explanations for the wasted aid and… the exaggerations, misrepresentations, and outright lies about the Haitian people that came both after the 2010 earthquake and for decades before it.”

Truth-telling is almost as difficult as truth-finding in Haiti, but Schwartz has managed to do both, at great personal risk and expense to himself. One only hopes that those who want to truly help Haiti, as well as Haitians themselves, overcome their naivete to recognize and appreciate the enormous value of “The Great Haiti Humanitarian Aid Swindle,” and use the book to reform, tame, or banish this reckless, unaccountable, injurious aid world with so many thieves, liars, and imposters posing as saviors and saints.