Last week we presented the first part of Dr. Timothy Schwartz’s analysis of why and how giant tent-cities of earthquake victims sprang up from metropolitan Port-au-Prince to Léogâne in the weeks after Jan. 12, 2010.

Published on his blog in May 2019 and adapted from a chapter in his 2017 book “The Great Haiti Humanitarian Aid Swindle,” the full article delves in depth into the struggle for housing and land in those days after the earthquake and throughout Haiti’s history. It is very worth reading but has been abridged for Haïti Liberté.

(The French translation of “The Great Haiti Humanitarian Aid Swindle” was just published in December under the title “L’aide humanitaire en Haïti: La grande escroquerie” and is available on Amazon.)

We left off last week with Dr. Schwartz demonstrating how the humanitarian aid community knowingly lied to the world about how many people were living in the tent camps. This week we examine why.

Kim Ives

So Why the Lies?

What we were seeing with the growing camps was in part a scramble to get aid that the humanitarian organizations were giving away. But what the humanitarian aid professionals and the press seemed to miss was that for the poorest people it was more about escaping rent payments and gaining access to free land, i.e. land invasion. Just like the poor and middle class throughout the world, urban rents are a huge burden for those who have to pay them. The first goal of most independent household heads is to own their own home, and the earthquake presented a golden opportunity to get one. (…) It’s interesting and useful because it helps us make sense of Haiti and the impact of humanitarian aid. But just as interesting, for me (…) was the exaggeration, indeed, outright lying from the humanitarian sector. For despite the obvious mathematical distortions, despite the fact that even common aid workers like Maria were aghast at the scale of the opportunism, despite that behind closed doors we all went on at length about the rampant opportunism, the leaders of the humanitarian aid community, like UN director Nigel Fisher, kept a straight face while bewailing to the press and overseas public absurd numbers of homeless. In that respect it was very much like the orphans and rapes. And just as with the orphans and rapes, lurking behind it all was pursuit of money from sympathetic overseas donors.

The Money

The NGOs were pouring aid into the camps. Or at least they appeared to be. Olga Benoit, the director of SOFA, the largest women’s organization in Haiti, (…) recounted that, “it was like an invasion of NGOs. They went to the camps directly. This camp was for CRS [Catholic Relief Services], this camp for World Vision, this camp for Concern.”

Some might think that’s alright. Why not? Even if many people in the camps were not direct victims of the earthquake, they must have been in need. Yolette Jeanty of Kay Fanm, the second major feminist organization in Haiti tells us why that really wasn’t alright: “The great majority of ‘sinistre’ (desperate people) were and still are inside the neighborhoods. Those people didn’t want to go to the camps, they stayed home. Even those in the camps, many don’t sleep there. They go home to sleep. They only come to the camps during the day to get water or whatever they might be giving away. But the NGOs, they all go to the camps.”

By ignoring the neighborhoods, the humanitarian aid workers were able to avoid (…) security. In the weeks after the earthquake, the press had not only sold a lot of newspapers with sensational stories of gangs and street battles, they had also frightened the hell out of everyone, not least of all the humanitarian professionals working for NGOs and UN agencies. In 2013, criminologist Arnaud Dandoy wrote about the absurdity of what he calls “moral panic” among the humanitarian community in Haiti.

The typical NGO headquarters in Port-au-Prince was secured behind 10 foot walls topped with concertina wire. Its employees were restricted by curfews, forbidden to even roll down their windows in certain neighborhoods or enter others, precisely those neighborhoods most in need of humanitarian aid. The camps solved a lot of problems.

Despite the fact that the NGOs and the grassroots organizations such as KOFAVIV were reporting skyrocketing violence, the camps could be patrolled. UN soldiers were stationed at camps where NGOs worked. Security experts could monitor the situation. And at night, when things supposedly got really bad, the aid workers weren’t there. They went back to the elite districts, to their apartments and hotel rooms located, once again, behind high walls and in guarded compounds. [11]

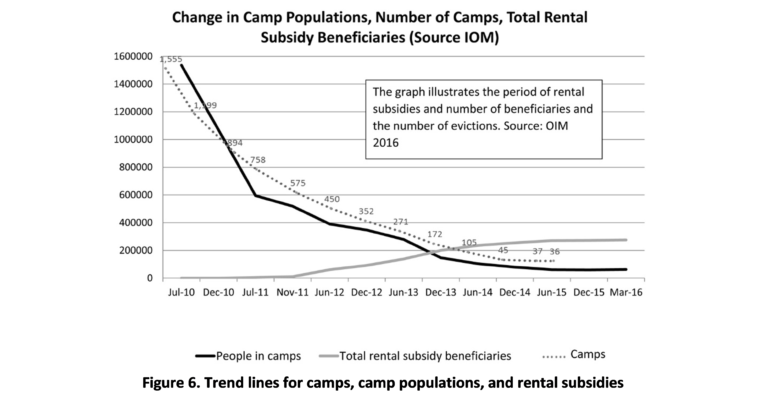

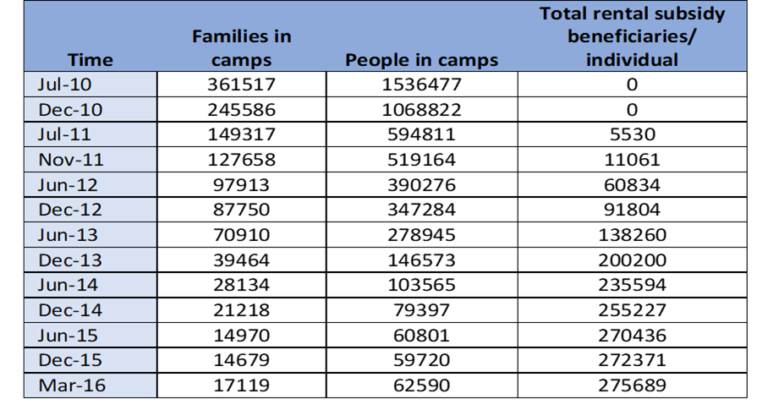

The problem with focusing on the camps, from a humanitarian perspective, is that they were missing a lot of the real victims. But what’s worse, from the perspective of helping, is that it was precisely the indiscriminate giving, the protection of the camps, and the carte-blanche certification of camp residents as legitimate that encouraged opportunists to pour into the camps. The camps grew for seven months after the earthquake, long after the last aftershock. They went from 370,000 people living “under improvised shelters” on Jan. 20, 2010 (IOM), to 700,000 on Jan. 31 (USAID 2010), to 1.3 million on Mar. 1 (UN 2010), to Nigel Fisher’s claim of 1.536 million in 1,555 camps on Jul. 9. Among those numbers were a lot of opportunists who sought to benefit from the aid, many of whom already had little grey concrete homes near the camps, homes that had not fallen down. And most of whom had some means of earning a living, however meager. And it’s unfair to those in need that such people would pretend to be victims left homeless by the earthquake. But more to the point here, it’s hard to overlook the fact that those who most benefitted from the lies and from permitting opportunists to indiscriminately pour into the camps were not the impoverished opportunists feigning to be homeless. Those who most benefitted from the lies were the foreign humanitarian aid agencies and their workers, many of whom were living in $50,000 per year hotel rooms and apartments. And it’s here where we can best understand why the United Nations and the NGOs were spewing untruths and omitting facts about the camps. [12]

The camps brought in donations. Whether deliberately or by default, the humanitarian aid organizations used the camps in much the same way as the people pretending to live in them: as aid bait to get overseas donors to give. The NGOs and UN agencies presented the camps to the overseas donors as a humanitarian aid smorgasbord of ills. Hundreds of thousands of vulnerable people in central locations with every imaginable need: food, water, shelter, security, lighting, sanitation, health, therapy. They were getting paid to take care of those ills. And by making a show of their efforts, taking lots of photo opportunities, it was as an easy solution to make it look like they were doing something. They didn’t have to go to the neighborhoods, didn’t have to implement rigorous mechanisms for vetting real victims from the pretenders. In this way the aid agencies essentially conspired with those pretending to live in the camps by not telling the truth about them and by wanton distribution of the aid. What makes it sad and distressing, if not criminal, is that those most in need, the weakest and most vulnerable who had gone to camps were, by and large, not getting aid. In the six years since the earthquake, I’ve listened to it over and over in focus groups:

“The camp committee took everything that was given for the camp. They took the tarpaulins and if you needed one you had to buy it from them for 250 or 300 gourdes. If not, you lived in the rain. Sometimes we saw trucks come with food. But they took everything to store at their houses. They didn’t give us anything. Some of these people had houses in good condition. The camps offered them more advantages than staying in their own houses.”

Erns Maire Claire (Female; 43 years; 3 children; teacher)

Focus Group for CCCM OCHA Cluster, Mar. 12, 2016

“What I saw happening was that they sold the food. Sometimes they made arrangements with other people and gave them food several times. These people sold the food and shared the money with them.”

Cadio Jean (Male, 43 years old; 4 children; mason/ironworker)

Focus Group for CCCM OCHA Cluster, Mar. 13, 2016

So there was waste and the NGOs were doing a lousy job getting the aid to the people who really needed it. There was massive embezzlement and hoarding. But if most of the people in the camps were not really earthquake victims and most were not getting anything from the humanitarian aid agencies, why did several hundred thousand people continue to live in camps for years after the earthquake? The answer is something that everyone seemed to speak about constantly but no one, not even journalists, seemed to realize was driving the camps. The answer is because they were renters and they hoped to get a piece of land and a home. Indeed, it was a consummation of Haitian historical trends, the invasion and expropriation of land, and most recently that of the invasion of Haiti by NGOs and the emergence of being a viktim as an opportunity to escape poverty. The poorest people and relative newcomers to the city were mobilizing their status as “earthquake victim” to seize land. (…)

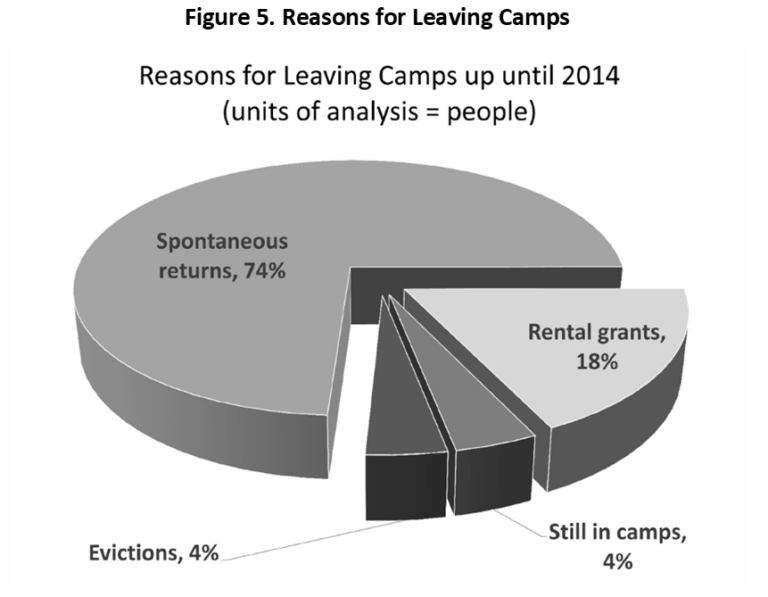

Spontaneously Disappearing IDPs

By December 2012, there were 347,284 people in the camps, down from the 1.5 million IOM had said were living in camps six months after the earthquake; 74% of them had simply left the camps, “spontaneously” according to IOM. It was not clear how many of the remaining thousands were holding out to see if they could keep the land they had their shelter on. Most revealing, over 90% of those who were still in the camps had been renters before the earthquake. But victims of the earthquake or not, the humanitarian aid agencies could not leave them as a reminder to the world of the failed post-earthquake relief effort. And so, a new plan was hatched.

In a strategy that critics denounced as “paying off the poor,” 80,000 families (representing 250,000 people) were given $500 toward a year’s rent. To make sure they really left the camps, the contract for the money was often given, not to the family, but to the owner of the rental unit where they were supposed to go live. The family had to move; then the tent was torn down; and then the money got transferred. Some 2 to 6 weeks after the move the aid agencies sent people in to verify if the people had really moved into the rental unit, and not simply partnered with a landlord to game the system. And in a move that seemed targeted to assure anyone who was lying to continue to do so—I by rewarding them for having lied in the first place–, they gave the recipients another $125—if they appeared to still be in the house.

How many really did move into the homes isn’t clear. The NGOs and UN claimed fantastic success rates. Red Cross evaluators found the results “extremely promising” explaining that “one year on, no grantees have returned to camps and 100% have autonomously found an accommodation solution. [59] Similar results can be found from evaluators for all the aid agencies, “100% satisfaction”, “90%” of all recipients really moved to the houses.” [60] [61]

How many really did move into the homes isn’t clear. The NGOs and UN claimed fantastic success rates. Red Cross evaluators found the results “extremely promising” explaining that “one year on, no grantees have returned to camps and 100% have autonomously found an accommodation solution. [59] Similar results can be found from evaluators for all the aid agencies, “100% satisfaction”, “90%” of all recipients really moved to the houses.” [60] [61]

Behind the scenes it wasn’t so pretty. In 2016, I was hired to lead a team of researchers for the United Nations Camp Coordination and Camp Management Cluster (CCCM Cluster), an agglomeration of 10 of the biggest humanitarian organizations involved in the rental subsidy program. Our task was to review their internal reports and then design and conduct a survey of 1,400 of those who had received rental subsidies.

The American Red Cross — under fire at the time for the now famous NPR investigation that revealed they had, despite getting $500 million in donations for Haiti earthquake victims, built a total of 6 houses — wouldn’t even give us the lists to find their beneficiaries. Neither did Sean Penn’s organization JP/HRO, which had spent some $8 million of World Bank funds to provide rental subsidies. When you read between the lines the deception was abundantly in evidence. Alexis Kervins, who managed the data for JP/HRO follow-up verifications, told me that 60% of the recipients had never even moved into the homes. In the survey we conducted for the CCCM Cluster, 80% of the phone numbers that the NGOs gave us on the contact lists were no good or no longer working.[62] The World Bank would note in its 2014, Rental Support Cash Grant Programs: Operations Manual that, “one interviewee gave some idea of the scale of the challenge when he noted that of 600 complaints received following registration at one camp, 70 were found to indeed live there.” In what was one of the few examples of a verifiable beneficiary list, Concern Worldwide wrote in an internal report that: “Over 3000 persons declared not having any ID during registration; however verification by local organization ACAT (contracted to provide birth certificates) found that the great majority of those persons do in fact have ID. ACAT’s verification brought down the number of paperless beneficiaries to 379 ….”[63]

In retrospect, the camps were one more version of the Great Haiti Aid Swindle. And just as with the rapes, orphans, the number dead, and all the other hyped afflictions the humanitarian aid agencies used to collect donations, they justified them with bad data, truth stretching and lies, all needed to fool the overseas public and legitimize the aid that was pouring in. The aid agencies knew what data was in their best interests and what was not. When the numbers didn’t add up, they came up with new numbers Was it impossible that 43% of the population were in camps? In one of the first major reports on the camps, U.S. university professor, activist-anthropologist and humanitarian aid researcher Mark

Schuller claimed that 70 to 85% of the people in Port-au-Prince had been renters before the earthquake. It was a number that got picked up by aid agencies and became part of the narrative. But Schuller had, deliberately or otherwise, mis-cited his colleagues Deepa Panchang and Mark Snyder who in a report had said, not 85%, but rather “up to 70%” of people were renters. And they were not referring to the population of Port-au-Prince.

They were referring to people living in the camps. Meanwhile, the real figure for proportion of the population that was renters at the time of the earthquake was, as seen, 40-50% of Port-au-Prince households, a figure that was available in several major and widely known studies. [64] [65] [66] [67] [68] [69] [70]

Another myth that justified camps was “skyrocketing rental costs.” Once again, this untruth came from the prolific Professor Schuller, who by this time had dubbed himself the “professor of NGOs” and was traveling to Washington DC to brief congressional committees on earthquake expenditures. Schuller cited UN data that rents had increased 300% since the earthquake, data that the aid agencies again latched on to.

Yet, using real income indicators, rental prices in Port-au-Prince slums where the same in 2010, 2011, and 2012 as they were in 1982 when author Joegodson’s father paid the equivalent of $209 for 1-year rental of a one-room, dirt floor shack with no latrine in Cité Soleil—one of Port-au-Prince’s poorest slums. As for the 300% increase in the cost of housing, Professor Schuller had been citing a UN report. But the UN wasn’t talking about the poor. They were talking about their own personnel who, along with NGO workers and consultants, were getting gouged while the rest of us who lived in Haiti, in popular neighborhoods, continued to pay the same rents.[71] [72] [73] [74]

Conclusion: Behind the Greed and Negligence

The misunderstandings, the failure to reach many of the most vulnerable, the lies about the numbers, the lies about opportunism, and the exploitation of the camps as “aid bait” to draw in donations were major features of the Haitian earthquake relief effort that should not be forgotten. Just as with the rescues, the orphans and the so-called rape epidemic, we shouldn’t allow politics, self-interest, and headline hunting journalists to impede our capacity to learn from the failures that came after the earthquake. But it’s important to make clear that the process is not some kind of conspiracy to mislead donors and benefit aid workers. Most aid workers who were present—from the lowest field worker to the highest directors—were as dismayed as I am with the waste, with the money that seemed to vanish, and with the failure to reach those who were most in need.

And many of the lowest level aid workers did not earn fat salaries. There were thousands of missionaries who earned nothing at all. There were people who paid to come to Haiti, who simply got tired of seeing the thousands of suffering Haitians on television, got off the couch, bought plane tickets, and came to Haiti to try do something about it. And even the high-level directors and administrators of humanitarian aid agencies are mostly good people who believe in what they are doing. I’ve known hundreds of them. The clear majority are compassionate people who set out to help, who wanted to change the world, alleviate poverty and suffering. But as they advance in the corporate world of charity, they get caught up in the industry of aid, the dreams get swept away and replaced by hope for a salary raise, a pension plan, a promotion, better working conditions, and the very real need to care for their own families. Turning on your employer and revealing that aid is failing is a fast way for an aid executive to lose those perks and get booted out of the business they and their families have come to depend on.

So it’s not the aid workers that we should blame for the failures. The issue is ultimately one of accountability. Those mega-aid institutions such as CARE International, Save the Children, and UNICEF depend on donations. The directors’ salaries and pension plans depend on those donations. The capacity for the organizations to be present in poor countries—no matter how wasteful and ineffective the organization is—all depends on getting donations. Their dependency on that money means the aid agencies must be pumping the public and the press with information that encourages people to give; their bureaucratic inefficiency means that there is never enough money; and the total absence of any mechanism to make the organizations accountable assures waste and failure to get the money to those for whom the aid was intended.

There are no institutional benefits to resolving these problems. There is no mechanism that assures that the organization that most effectively spends the money and helps people out of poverty will get the most money. On the contrary, It’s not about effectively spending the money; it’s about getting the money. The most donations go to those who exaggerate and lie the best. The profit motive is getting donors to give, selling images of extreme need and suffering: vulnerable children, orphans, child slaves, rape victims, homeless people. And they need that money to keep going, to keep the directors paid, keep the organization alive. It’s those needs that assure the problems will be exaggerated and the accomplishments, no matter how pathetic, will be hyped. It assures they will always hide the truth. And no matter how ineffective an aid agency is, those idealists working for the organization can always latch on to the belief that yes, there were mistakes in the past, but it’s all about to change, and they’re part of that change. But you can’t make change happen if the money stops. And in what becomes a fierce competition of making afflictions up, a type of arms race of lies, the money goes to those with the most fantastic tales. And so in the absence of any mechanism to vet those lies and censure those organizations behind the lies, the experts and professionals go right on pumping out untruths and sabotaging their own efforts to help the poor.

NOTES

[11] For Arnaud Dandoy’s analysis of “moral panic,” see, Insecurity and humanitarian aid in Haiti: an impossible dialogue? Analysis of humanitarian organisations’ security policies in Metropolitan Port-au-Prince. Groupe URD (Urgence – Réhabilitation – Développement)

[12] For Nigel Fisher claims see: UN Office of the Special Envoy for Haiti. 2010. “Haiti: 6 months after… UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti.” Published on July 09, 2010 http://reliefweb.int/report/haiti/haiti-6-months-after

[54] Regarding the documentary “Where Did all the Money Go” by Michelle Mitchell, my opinion of the film was that it was narrow, demagogic attack on the NGOs from a journalist who depended heavily on activists such as Scott Snyder and Professor Mark Schuller. The film nevertheless stirred up a storm in driving home the undisputable fact that people in the camps in fact got very little of the aid money. The next question was, of course, if the camps didn’t get it—and the NGOs were claiming that it was the camps that were getting most—then where did the money go. Indeed, it became almost a cliché: “Where did all the money go?”

[55] Ratnesar, Romesh. 2011. “Who Failed on Haiti’s Recovery?” Time, January 10. http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2041450,00.html

[56] Doucet, Isabeau. 2011. “The Nation: NGOs Have Failed Haiti,” NPR. January 13. http://www.npr.org/2011/01/13/132884795/the-nation-how-ngos-have-failed-hait

[57] Salmon, Felix. 2011. “Where Haiti’s money has gone,” Reuters, August 22. http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2011/08/22/where-haitis-money-has-gone/

[58] Schuller, Marc. 2011. “Smoke and Mirrors: Deflecting Attention Away From Failure in Haiti’s IDP Camps.” Huffington Post. December 22, 2011.

[59] See, Rana R., Condor J. and Juhn C. 2013. “External Evaluation of the Rental Support Cash Grant Approach Applied to Return and Relocation Programs in Haiti.” RSCG Programs – Operational Manual. Wolfgroup Performance Consultants.

[60] See: Socio-Dig. 2016. “Final Report for Comparative Assessment of Livelihood Approaches Across Humanitarian Organizations in Post-Earthquake Haiti Camp Resettlements.” Concern Worldwide. September 22.

[61] For data on the number of camps and population sizes of the camps see, United Nations. 2011. HAITI Camp Coordination Camp Management Cluster DTM v2.0 – Update – March 2011 1 DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX V2.0 UPDATE March 16, 2011. www.cliohaiti.org/index.php?page=document&op=pdf.

[62] A quick summary of findings from the survey we did on behalf of the CCCM cluster: Of the 20% of phone numbers that worked, we drew a sample of 1,400 people and we went to their rental home and interviewed each for over an hour. We asked detailed questions about everything from where they lived and what they owned before the earthquake to what they owned in the camp and now. We asked about medical care, people who had been sick and died. And we asked about occupations. What we found was more of the adult women in the sample (household head and/or spouse of male household head) were uneducated, and clearly many of the households were dirt poor. But the findings did not significantly differ from the rest of Port-au-Prince: 89% had phones, 53% had televisions; 14% of the women were traders, and 18% of those regularly traveling to the Dominican Republic to buy goods for resale, one unthinkingly reported that she goes to Miami to buy goods; 32% of the men and 13% of the women were skilled workers such as masons, electricians, tailors and seamstresses. There were 39 drivers, 18 motorcycle taxis, 23 civil servants, 16 fisherman, 19 school teachers, 1 policeman. None of the people we interviewed had been out of the camps for more than three years, most less than two years, but 8% had purchased land in Port-au-Prince; 32% already owned land in rural areas. As for the 40% who really were not doing well and had moved out of their rental unit, 30% moved into to homes with family and friends, 10% moved back into tents or camps. 20% no longer had a toilet or even an outhouse. And these were the people we could find. I could go on and on with this. But the bottom line was that there was nothing unusual about the population of camp dwellers. Overall they were not the poorest of the urban poor as illustrated by finding such as only 27% of the Subsidy Sample vs. a higher 30% of the general population was without a television at the time of the earthquake; 5 vs. 15% lived in a house with a dirt floor, and 4 vs. 15% were without a toilet. Not least of all the average rent that subsidy sample respondents reported paying per year at the time of the earthquake was 13,240 HTG (US$331), much lower than the US$40 annual rent that UN Habitat estimated in Site Soley in year 2009.

[63] For the quote regarding only 379 of 3,000 people claiming to have lost their ID cards being legitimate see, Concern Worldwide Report to the European Commission – Directorate General – Humanitarian aid and Civil protection – ECHO eSingle form for humanitarian aid actions App_version AgreementeSingle form for humanitarian aid actions App_version Agreement; page 6.

[64] The point is that those working for aid agencies deliberately pick and chose the data they would pass on to the press and in other cases outright twisted their own data to suit their narrative. Put another way, obvious facts, logical deductions, and representative statistical studies did not deter those bent on arguing that the camps were inhabited almost wholly by legitimate earthquake victims and homeless people. Instead of trying to understand the results and acknowledging widespread opportunism—something that would have put the humanitarian agencies on the track to helping those really in desperate need—the reaction to any contradiction was swift and defensive. IOM spokesman Leonard Doyle told The Miami Herald:

“It stretches the credibility to suggest that there are less than 100,000 [internally displaced persons] in camps when we physically counted 680,000 in March… A few camps in Port-au-Prince easily exceed their IDP number.”

No one had said that there were not real IDPs. No one had ever said that there were not 680,000 people in the camps at the time the BARR was published. Certainly not me. The issue was who were those people and how many of them were from destroyed homes. And more to the point regarding what can only be understood as yet one more twisting of the data to suit their needs, Doyle and everyone else working for IOM knew that what he said was not true. Five months before Doyle made the statement to the Miami Herald, IOM had done a survey of 1,152, camps and found that at least 25 of all tents in the camps were empty (See following endnote).

[65] In January and mid-February 2011, precisely while we were carrying out the BARR, and when IOM was reporting to the press that there were 806,377 IDPs in 1,152, camps, IOM and its partners ACTED had been completing another survey. Their field teams visited 1,152 IDP sites. What they found was that 92 of those sites had only empty tents. That’s almost 10% of all the sites. All empty tents. Of the 1,061 camps that did have tents with people living in them, 712 were found to contain at least some empty tents. What that meant varied. In one area (Ganthier), 73% of the 213 tents were empty. 155 empty tents were empty that hosted a total population of 58 Households. In the commune of Croix-Des-Bouquets, 6,525 tents located on 63 sites were empty; that’s 30% of all tents in that area. In the southern regions of Grand Goâve 736 empty tents located on 34 sites were empty: 49% of tents all tents in that area. In Léogâne, 1,770 tents located at 74 IDP sites were empty; 36% of all tents in that area. Overall, combining the empty tent cities with the empty tents, we can infer that 25% of all tents in the IDP sites that IOM checked were empty. As for how many of the 75% of the remainder had people how actually lived in those tents, we don’t know. But IOM did report that the average household size was 4.1 and in some areas as low as 3.3, compared to 5.2 to 5.8 for Port-au-Prince homes in general. To their credit, IOM interpreted this as suggesting that, “some IDPs have decided to keep some household members in the IDP sites so as to retain access to services in the sites, while other family members return or resettle elsewhere.”

All the proceeding came from an unpublished summary. But those interested in a reference and official summary may go to, United Nations. 2011. HAITI Camp Coordination Camp Management Cluster DTM v2.0 – Update – March 2011 1 DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX V2.0 UPDATE March 16, 2011 www.cliohaiti.org/index.php?page=document&op=pdf.

[66] After the BARR was published, Doyle wrote to me and complained,

I’m trying to square your figures with the DTM which recorded 680,000 camp residents in March and a fraction lower in an upcoming report. This is based on a direct headcount, usually at 6 am, when the researchers go to camps. Heads of family get a registration card. It seems hard to game that system as it’s an actual count.

(Personal communication, e-mail, May 30th, 2011)

He knew that people in the camps had not been registered during 6 a.m. head counts. IOM had set up tables whereupon people lined up and registered themselves.

[67] IOM did report that the average household size was 4.1 and in some areas as low as 3.3, compared to 5.2 to 5.8 for Port-au-Prince homes in general. To their credit, IOM interpreted this as suggesting that, “some IDPs have decided to keep some household members in the IDP sites so as to retain access to services in the sites, while other family members return or resettle elsewhere.

[68] The IOM/ACTED survey also found that 17% of respondents reported they wished to return to their original homes, 12% said they wanted to leave Port-au-Prince and go back to the countryside. Some 11% said they needed more information to decide, 10% said they wanted to go to a planned site, while 9% were prepared to return to their own home, even if it was not repaired. Finally, 19% said they had no place to go.

This survey provides factual-based evidence of the need to communicate more and in a better way with the earthquake affected population. All humanitarian partners need to better assess the information needs of these communities to be able to adapt and design relocation and return projects according to the needs and concerns expressed by displaced people.

See, ACTED. 2011. “Enquête IOM – ACTED. Intentions Des Deplaces Haïti.” May 8,-2012

[69] As seen elsewhere, activist-anthropologist Marc Schuller became one of the most ardent defenders of the ‘legitimacy’ of the camp residents and in doing so was an important bulwark of mis-information for the aid agencies. In a US National Science Foundation funded surveys that Schuller conducted in IDP camps, 3.5% of the respondents reported having immigrated to Port-au-Prince after the earthquake. Extrapolating that to the general population meant, Schuller was saying, meant if there were 100,000 people in camps, 3,500 were from areas outside of Port-au-Prince, i.e. had come from outlying cities and rural areas after the earthquake (most people in Port-au-Prince were in fact born outside the metropolitan area) . It’s a testament to the honesty of some of those people in the camps that they admitted they arrived after the earthquake. It also illustrates the extent to which the camps served—even without the aid—as an advantage to the poor, i.e. they did not have to pay rent. But Schuller used that finding to argue that::

To the concern about the free aid being a magnet pulling tens of thousands of people from the provinces, the survey showed only 3.5% came since 2010, with the mean year of migration to Port-au-Prince being 1993, which follows the general pattern of Haiti’s rural exodus. Simply put, all but 3.5% are “real” IDPs.

It’s a rather bizarre conclusion. Only people who arrived from the rural areas after the earthquake could be ‘fake’ IDPs? It also suggests a type of condescension on the part of Schuller to assume that the people in the camps were so simple that they would not have had the good sense to appear to surveyors that they had been displaced by the earthquake thereby assuring that they would partake in any aid and perhaps even be given land, a home, or at the very least one free year rent. Those that did say they arrived after the earthquake assured themselves of getting nothing in the end, except evicted.

[70] Regarding home ownership in Port-au-Prince: in fact, surveys before the earthquake estimated that 42% of Port-au-Prince residents were homeowners (see page 53 of FAFO 2003 Enquête Sur Les Conditions De Vie En Haïti ECVH – 2001 Volume I).). In the USAID/BARR (2011) survey we found that 70% of Port-au-Prince respondents claimed to own the house they lived in, 60% claimed to own the land, 93% of these had some kind of paper. Notable as well is that the USAID/BARR census of Ravine Pentad (2010)—one of the Port-au-Prince neighborhoods most impoverished and most severely damaged in the earthquake—found that 60% of respondents owned the house; 51% owned the house and land. The discrepancy in the differences between the USAID surveys and that of the 2001 ECVH is due to the latter not have differentiated between ownership of the house and ownership of the land. As seen in the USAID surveys, a common practice in popular neighborhoods is to build homes on rented land and subsequently purchase the land. Rents for land are typically 1/10 to 1/20 that of the rent for home. In a 2012 survey I designed and coordinated for CARE International we visited 800 randomly selected homes in Léogane and found that 72% of household heads reported they owned the land and the house. In a CARE funded survey of heavily urbanized Carrefour we found that 50% of 800 randomly selected household heads claimed to own the house and the land; 60% owned the house.

[71] For Schuller’s claim that the cost of housing had increased 300%, see: “UNSTABLE FOUNDATIONS: Impact of NGOs on Human Rights for Port-au-Prince’s Internally Displaced People.” Oct. 4, 2010, page 4.

[72] For Schuller’s mis-interpreted citation of 70-85% of Port-au-Prince population that was renters before the earthquake, see Deepa Panchang and Mark Snyder who had written are report entitled, “We Became Garbage To Them Inaction And Complicity In IDP Expulsions A Call To Action To the U.S. Government” (Aug. 14, 2010). As seen in the text, Panchang and Snyder—both highly productive activists in the months and years following the earthquake—had in fact not said 85%, but rather “up to 70%.” And they were not referring to the population of Port-au-Prince but rather to the population of the camps. Specifically, they cited IOM camp registrations as their source: Registration Update, Feb. 25-Jun. 25, 2010. “Haiti Camp Coordination Camp Management Cluster.” International Organization for Migration.

For Schuller’s claim that “An estimated 70-85% of Port-au-Prince residents did not own their home before the earthquake.”, see: “UNSTABLE FOUNDATIONS: Impact of NGOs on Human Rights for Port-au-Prince’s Internally Displaced People.” Oct. 4, 2010, page 4.

[73] In the case of Schuller it was more likely deliberate prevarication for a noble cause, helping the poor, which is respectable but presumptuous of Schuller to second guess the data and assume that he knew what was in the best interest of the poor.

[74] One World Bank report claimed that before the earthquake Haiti had a deficit of 500,000 residence units, which taken literally would have meant that 1/4 the entire population lacked a home—again, that’s before the earthquake. Given that there are 5.2 people per household, that would have amounted to 2.6 million people, about 1 million more than lived in Port-au-Prince before the earthquake and about 75% of all the people living in the entire strike region. I suppose it depends what one considers ‘residential unit.’ The report did not say. (see: World Bank. 2015. “Home Sweet Home: Housing programs and policies that support durable solutions for urban IDPs.” Page 3).