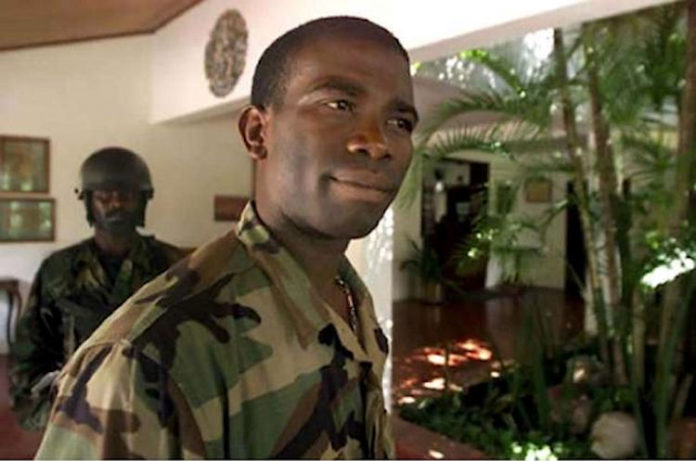

Former paramilitary leader Guy Philippe will be going to jail for money laundering in connection with drug trafficking. But his more serious crimes were murdering Haitians and Haitian democracy as the leader of the “armed opposition” during the Feb. 29, 2004 coup d’état against former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

In the early 1990s, Emmanuel “Toto” Constant headed another anti-Aristide paramilitary organization known as the Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti (FRAPH), which played a large role in killing an estimated 5,000 during the 1991-1994 coup d’état.

Like Philippe, Constant was never tried for his crimes against humanity. Instead, in 1996, the Clinton administration gave him de facto political asylum in the United States. However, in 2008, he was convicted in New York of mortgage fraud and is currently serving a 12-37 year prison sentence.

If he had gone to trial in May and been convicted, Philippe faced a life term for drug trafficking. Instead, he struck a plea deal with federal prosecutors whereby he will likely serve only 7.5 to 9 years in jail.

Although serving terms for lesser offenses, Constant and Philippe are both part of a murderous paramilitary continuum in Haiti that can be traced from François “Papa Doc” Duvalier’s Volunteers for National Security (VSN), commonly known as the Tonton Macoutes, to the death-squads that continue kidnapping and murder in Haiti today.

In 2012, University of California at Santa Barbara-researcher Jeb Sprague published “Paramilitarism and the Assault on Democracy in Haiti” (Monthly Review Press), which analyzes the history of Haitian paramilitarism and its leaders. Haïti Liberté is currently publishing in French a series by Sprague entitled: “Haïti: le capitalisme des paramilitaires.”

For the next three weeks, we will publish in English excerpts from “Paramilitarism and the Assault on Democracy in Haiti” to provide readers with background on Guy Philippe’s real crimes, which are much more serious than those for which he will do time in the U.S..

Kim Ives

From Chapter Three: “The Return of Paramilitarism: 2000–2001“

The earliest phase of the new paramilitary campaign to destabilize and topple Haiti’s democracy began in October 2000.

This chapter examines the first stage of this renewed campaign of paramilitary terror, beginning in 2000. Numerous interviews I conducted provided details on the formation and early activities of the paramilitary organization known as the Front pour la Libération et la Reconstruction Nationale. The FLRN was composed of individuals who had formerly served as police, military, and paramilitary forces in Haiti. Little has been written of FLRN activities in its early years of existence and about the role of a collection of hard-line Haitian rightists and Dominican government officials in supporting this paramilitary force. I provide a detailed account of the role that a small group of elites early on played in facilitating the paramilitary campaign.

THE INITIAL PLOT

Backed by Haiti’s popular movement to run again for president, Aristide announced his candidacy under the Fanmi Lavalas [FL] banner on Oct. 2, 2000, the deadline for candidates to register for the Nov. 26 presidential election. Haiti’s president was then René Préval, who had served as prime minister for Aristide’s earlier administration (from February 1991 until the coup d’état of September 1991). In 1990, Préval, along with his and Aristide’s close friend, progressive businessman Antoine Izméry, had encouraged Aristide to enter politics. But after 1995 Préval and Aristide began to drift apart as Préval veered to the right, supporting privatization and dropping some of the popular programs Aristide had promoted.

By 1:00 p.m. on Oct. 3, 2000, a large crowd of FL supporters had gathered in front of the Conseil Electoral Provisoire d’Haiti (CEP) offices on Delmas Avenue in Port-au-Prince. This gathering, many participants relatives or friends who had been victims of the various military dictatorships, celebrated the former president’s entrance into the race, which symbolized for them the return to more bold and progressive politics. However, when Delmas police chief Jacky Nau angered the FL crowd by roughing up a Lavalas militant, Ronald “Cadavre” Camille, the crowd reacted as Nau claimed he was only attempting to disarm Camille.

As it happened, both sides had reason to be upset and suspicious. Camille was a murky figure, allegedly involved in murder and other criminal activities, yet many in the crowd resented the brutal anti-democratic tactics of some members of the police, especially those from the ex-FAd’H contingent that served in the [Haitian National Police] HNP’s feared anti-gang unit. Camille, who had started dealing marijuana on the streets of Port-au-Prince at a young age, had been involved in protesting the Cédras regime in the early 1990s and had survived torture at the hands of the army.(1) But Nau, part of the group known as “the Ecuadorians” that now served as police chiefs, had become known for a particularly brutal brand of justice. He had grown up attending St-Louis de Gonzague, the private school in Port-au-Prince attended by some of Haiti’s most privileged children.

From a U.S. embassy cable: “Local radio reported that a group of musicians pulled ‘cadavre’ away and helped calm the situation.” (2) The standoff was resolved without anyone being physically harmed, but as Haiti Progrès reported afterward, Ronald “Cadavre” was “never called to account, and the infuriated Nau began meeting with another police commissioner, Guy Philippe, and other officers to discuss what should be done.” (3) Nau and Philippe, along with a few other dissident police chiefs (who were also ex-military), soon began laying the groundwork for a coup. Philippe claims he had been working on plans to bring down the government since the year prior. (4)

From the start, the conspirators were in contact with hard-line sectors of the elite, including some neo-Duvalierists and industrialists with strong ties in the Dominican Republic. Believing it was necessary to act quickly, the conspirators saw fit to carry out what they described as a “preventive coup,” overthrowing Préval before the inauguration of Aristide in early February of the following year. (5)

The group of anti-government police chiefs planned their attacks over three days in November. (6) The plotters held a preliminary meeting with U.S. officials, likely hoping to gauge their level of support for the action, which the U.S. embassy later claimed was an attempt on their part to “have the men drop the idea of a coup.” (7) The “putschists” reportedly told “U.S. officials that the coup was already too far along and that abandoning it would place the group in greater danger.” (8) The fact that U.S. officials were at a meeting with police chiefs plotting a coup underscores the close relationship that the U.S. embassy and intelligence agencies maintained with the ex-military and their elite backers. However, it is also clear that at the time senior U.S. policymakers in the Clinton administration did not want a coup. Hundreds of millions of dollars had been invested in Haiti over the past five years, even as Washington’s unease with Haitian political institutions had grown. Large programs had been put in place to rebuild Haitian institutions, and the Clinton administration, which had backed the restoration of democracy in 1994 (though manipulating it at the same time), was still in office. Refusing to back down, the coup plotters planned to execute President Préval, along with Aristide and rogue Lavalas senator Dany Toussaint, who traveled with a heavily armed security escort. (9) The rebel police chiefs and their backers then planned to put Minister of Finance Fred Joseph on trial.

The plan for the immediate aftermath of the coup d’état was to place a new government in the National Palace headed by Olivier Nadal, a wealthy opposition leader and onetime president of the Haitian Chamber of Commerce; Léon Manus, president of the CEP then living in the United States (Manus had received a U.S. visa when he claimed he had come under intimidation by the Préval government that same year); Guy Philippe, a police chief in Cap-Haïtien and the most charismatic and educated of the dissident police chiefs; and Jean-Claude Fignolé, a historian and longtime friend of the plotters (who allegedly helped pay for Guy Philippe’s schooling in Ecuador and St. Louis de Gonzague).

Philippe joined the FAd’H as a cadet in 1993 during the Cédras regime. He claims to have received a military scholarship from the Escuela Superior de Policia de Quito, where he trained from September 1992 until August 1995, learning the techniques necessary for what he describes as the “preservation and restoration of public order in a democratic state.” (10) Under U.S. auspices once the FAd’H was demobilized, Philippe was placed in 1995 in Haiti’s new \ police force. (11) With the police force torn by internal divisions and corruption and the Préval government under mounting U.S. pressure to rein in street gangs in some of Haiti’s poorest neighborhoods, Philippe played a key role in coordinating some of the operations meant to “pacify” these areas. (12) Philippe quickly came under criticism from human rights groups for his activities as police chief; his raids had resulted in numerous civilian casualties. (13) Philippe “owed [his] success to a reliance on violent methods,” with some policemen under Philippe’s command “accused of staging extra-judicial executions.” (14)

Philippe has alleged, in justification for his actions that under Aristide’s personal orders a number of opposition figures were executed, though such claims have never been substantiated. He claimed that Aristide was connected to the murder of Mireille Durocher Bertin, a politician who had supported the military regime and was assassinated in March of 1995. (15) This charge against Aristide has been made for years by Haiti’s ultra-right; the paramilitaries and their backers utilized such allegations to justify their own violent activities against Haiti’s government and popular classes. In the case of Bertin, a year-long FBI investigation after the killing never turned up any evidence connecting the killing to Aristide (in fact, evidence pointed toward other suspects and some of Bertin’s murky connections). Numerous groups would have profited from her death, and U.S. officials ended up claiming that a narco link between a friend of Bertin’s and a clique within the government may have been responsible (alleging, although never proving, that Dany Toussaint was one of those involved). (16) Whereas opponents of Lavalas have often blamed Aristide, his elected government, or the popular classes for violence during the period, the few high-profile acts of violence that have been linked to the Lavalas camp appear to be allegedly associated with a small group around Dany Toussaint. This is a fact that has largely gone ignored — as has the internal conflict in the police at this time, such as that between Toussaint’s group, the “Ecuadorians,” and others around onetime police chief Bob Manuel, who served as Secretary of State for Justice and Security under Préval’s government.

Even with all of these problems and contradictions, and under significant pressure and destabilization, the popular movement and much of its leadership proved resilient. Some of Aristide’s strongest support radiated from the slums where the rightist military was most despised, where the brutal operations of paramilitaries, the former army, and the anti-gang units of the police had cost many lives. Opposing the heavy-handed violent approach of Philippe and his ex-FAd’H counterparts in the new police force, Aristide and other Lavalas leaders advocated for an alternative solution, the construction of a civilian police force in conjunction with government-sponsored negotiations between warring factions in Haiti’s slums, with Aristide himself promoting peace talks between warring gangs in Cité Soleil and other poor neighborhoods. But such moves were extremely difficult to carry out, especially as elites and their mercenaries continued to ruthlessly assault the democratic movement. Claiming to have seen half a dozen murders of opposition members and the humiliation of his friend the Commissaire de Police Jacky Nau, Philippe says that by late 2000 there was “no doubt that I was ready to support the opposition to Aristide in all its forms.” (17) In mid-October 2000, news of Philippe’s planned coup began to leak out in Haïti Progrès:

A U.S. military officer earlier this month hosted meetings by men conspiring to make a coup d’état in Haiti in November… Haitian authorities learned of and foiled the plot last week… According to our confidential source, two meetings were held at the private residence of a U.S. Military Attaché in Haiti, a certain [U.S.] Major Douyon, on Oct. 8 and Oct. 11. At the first meeting, there was discussion of delivering U.S. visas to certain police chiefs. At the second meeting, there was a call for mutiny to take action against Lavalas demonstrators [chimères], with whom one police chief had trouble earlier this month. (18)

The U.S. officials participating in the meetings were Major Douyon, the U.S. military attaché in Haiti, and Leslie Alexander, U.S. chargé d’affaires. (19) Toward the end of October, the would-be coup plotters were betrayed. Officials within the U.S. embassy alerted Haitian authorities about the seditious meetings at Douyon’s home. Whereas conservative sectors within the U.S. government (GOP in congress, CIA, and Pentagon) had long backed campaigns to topple Haiti’s pro-democracy movement, the Clinton administration sought to maintain the status quo to some extent, allowing the elected Haitian government to remain in office while withdrawing some aid and funding projects routed through the government, a strategy meant to slowly starve the aid dependent Haitian state, thereby forcing it to step in line. Meanwhile, in an account confirmed by a senior U.S. official, the Washington Post reported that a coup was to take place in November. (20) The armed rightist sectors, the only force capable of carrying out such a strategy, continued to pose the greatest risk to Haiti’s democracy.

Aristide’s dissolution of the army in 1995 had created a large pool of eligible and resentful ex-military labor. Many of these soldiers had been trained in or by the U.S.. Many hundreds of them were later integrated into the (consequently) volatile and unreliable police force. No doubt the best and most efficient option would have been a single coordinated uprising by the PNH [HNP] itself, preferably before Aristide’s official return. (21)

Upon being alerted about the planned coup, national police director General Pierre Denizé summoned the police chiefs to a meeting: Guy Philippe; Jean-Jacques Nau; Gilbert Dragon, a police chief in Croix-des-Bouquets; Millard Jean Pierre, a chief in the upscale neighborhood of PétionVille; and police chief Riggens André of the Carrefour district. Following the meeting, Denizé reported back to the National Palace that they had all claimed to know nothing of the unauthorized meetings at the home of the U.S. military attaché. Soon after Préval returned to Port-au-Prince from a trip to Taiwan, he ordered an intensified investigation into the alleged coup plot. (22)

Meanwhile, peasants in Fermathe, an area in the mountains above Port-au-Prince, witnessed large movements of armed men — as many as 200 by one account. (23) Military training exercises had been spotted at the home of Patrick Dormeville, a former police official at Port-au-Prince’s Toussaint L’Ouverture International Airport. Radio Kiskeya reported that up to “600 policemen” were involved in the possible coup attempt. (24)

Grasping the advanced nature of the coup plot, Denizé called again for the five police chiefs to rendezvous at his office. Upon hearing this and obviously fearing arrest, Guy Philippe, Gilbert Dragon, and Nau fled. (25)

Leaving Port-au-Prince, Philippe explains that he and his comrades “drove as far as Ouanaminthe in [his] own Nissan Pathfinder.” (26) On the night of Oct. 17, six police chiefs, along with an unverified number of dissident police officers and former military men, fled Haiti across the Dominican border into the dusty border town of Dajabón, where industries employed low-cost Haitian labor. The town was heavily patrolled by Dominican police and private security forces. (27)

Notes

- From author’s 2011 interview with a onetime close friend of Camille who requested anonymity.

- Kenneth A. Duncan, U.S. embassy, Port-au-Prince, Cable 8D1713, Oct. 3, 2000.

- Edward Cody, “Haiti Torn by Hope and Hatred as Aristide Returns to Power,” Washington Post, Feb. 2, 2001.

- Referring to the plans for a coup, Philippe stated: “I had my strategy since about 1999.” Transcript of interview with Guy Philippe, Scoop FM 107.7 FM, Port-au-Prince (September 2011).

- A preemptive coup was attempted in January 1991, just before Aristide was inaugurated into his first term of office.

- “The Autopsy of a Failed Coup,” Haïti Progrès, Oct. 25–31, 2000.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Peter Hallward, “Insurgency and Betrayal: An Interview with Guy Philippe,” Haiti Analysis, Mar. 24, 2007, available at www.haitianalysis.blogspot.com. In his 2007 interview with Hallward, Guy Philippe claimed that his tell-all book, The Time of Dogs, or Le Temps des chiens, would be published in 2012. With the return to Haiti of Jean-Claude Duvalier in January 2011 and the political make-over of Michel Martelly, winning an “election” in which around 75% of registered voters did not participate, the time now appears ripe for Philippe to publish his book.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. Philippe states that Pasteur Leroy was part of a coup plot in 1996: “In 1996 I heard that there were plans being prepared for a coup d’état, and Léon Jeune and Pasteur Leroy were at the head of this movement. I was in Ouanaminthe at the time and did not play an important role in the police operation against it; on the other hand the police arrested Jeune in 1998, when I was police chief at Delmas.”

- Michael Karshan, conversation with the author, Port-au-Prince (2011). The FBI ran an intensive investigation into the killing and turned up nothing linking Aristide to the attack. Bertin’s involvement with people involved in the drug trade appears to be at the root of what happened. But Bertin had a lot of enemies herself. In 2007, I interviewed her widower, Jean Bertin, who had for some time been working for the foreign ministry of the Dominican Republic in Santo Domingo, operating closely with Dominican officials who had befriended the FLRN paramilitary leadership.

- Hallward, “Insurgency and Betrayal.”

- “The Autopsy of a Failed Coup,” Haïti Progrès. An aid to the Clinton administration’s special envoy to Port-au-Prince, Don Steinberg, relayed to Haitian prime minister Jacques Alexis “intelligence that Nau, Philippe, and others were discussing what could be the beginnings of a coup.” Several days later “Steinberg went to see Aristide at his home with the information, warning that Aristide and Préval could be assassination targets.” Steinberg reportedly handed over a dossier with notes from the meeting which outlined how a small group within Haiti’s police force, mostly former FAd’H, were planning a coup.

- Ibid.

- Cody, “Haiti Torn by Hope and Hatred as Aristide Returns to Power.”

- Hallward, Damming the Flood: Haiti, Aristide, and the Politics of Containment (London: Verso, 2008), 121.

- Cody, “Haiti Torn by Hope and Hatred as Aristide Returns to Power.” The human rights abuses carried out by the anti-gang unit of the HNP while under Philippe’s command during the late 1990s occurred mostly in the neighborhoods of Delmas 32, 33, and 75.

- “The Autopsy of a Failed Coup,” Haïti Progrès.

- Ibid.

- Only two police chiefs, Millard Jean Pierre and Riggens André, came to the meeting. Apparently the plotters needed more time to put their plans into action. From that moment, “the gravity of the situation became clear, since one of the fugitive chiefs conveyed to authorities that he and his cohorts were military tacticians and ready to defend themselves against any attempt to arrest them.” Reported in ibid.

- Hallward, “Insurgency and Betrayal.”

- “The Autopsy of a Failed Coup,” Haïti Progrès.

[…] overwhelmingly popular President Aristide over a bloody three year military campaign, which claimed the lives of hundreds of Haitian police officers, cadets, and […]

[…] overwhelmingly popular President Aristide over a bloody three year military campaign, which claimed the lives of hundreds of Haitian police officers, cadets, and […]