Last week, we learned how a cabal of Haitian police chiefs, who had been trained in Ecuador (therefore known as the “Ecuadorians”), attempted to organize a preemptive coup in October 2000 to prevent former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s reelection in November 2000 and return to power in February 2001

Their plot discovered by Haitian authorities, the police chiefs fled to the Dominican Republic, where they began to set up the Front pour la Libération et la Reconstruction Nationale (FLRN), of which Guy Philippe became the leader. Its goal was to remove Aristide from office through a coup.

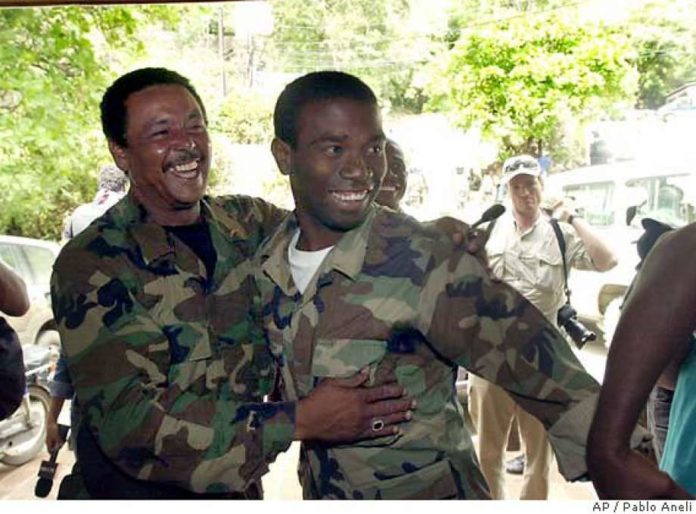

This week, we learn how Philippe connected with FRAPH death squad leader Louis Jodel Chamblain and former Haitian soldier Remissainthe Ravix to build the force, all with the connivance of Dominican authorities.

Kim Ives

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC SHELTERS CONSPIRATORS

The Oct. 23, 2000, edition of the Dominican daily Listín Diario reported that the Haitian police chiefs “crossed the border with the assistance of members of the Dominican Armed Forces in Dajabón and Monte Cristi.” (35) In Dajabón, which was home to thousands of Haitian migrant workers, few were likely happy to see Philippe and his fellow military men, especially as paramilitaries had often been used to attack striking workers, or to intimidate and assassinate trade unionists. Late at night, local workers encircled the hotel that the ex-military men were staying in; some were intent on lynching the men inside.

In response to the furor, Dominican soldiers intervened and evacuated Dragon, Philippe, and the others by helicopter to Santo Domingo, where the Dominican military held them in protective custody.(36) They were questioned by officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a hotbed staffed by anti-Aristide bureaucrats with career positions.(37)

Days after the ex-police officers’ arrests, Haitian foreign minister Fritz Longchamp traveled to the Dominican Republic to request their formal extradition. The Haitian president publicly and formally requested the surrender of the former police officers, and accused them of being involved in a planned coup d’état.(38) But Dominican authorities refused to hand over the coup plotters, claiming a right to grant them political asylum.(39)

Dominican officials quickly announced that the ex-police had been “given asylum in Ecuador,” a destination likely facilitated by U.S. officials who had helped train the Haitian military and were now operating an air base in the Ecuadorian port city of Manta.(40) But by early 2001, the ex-police officers were already back in the Dominican Republic with other former members of the FAd’H [Armed Forces of Haiti], such as former soldier Remissainthe Ravix, and getting tactical advice from the infamous [FRAPH] death squad leader Louis Jodel Chamblain.

Strategizing with a handful of elites from Haiti’s “civil society” opposition, Philippe acknowledges that from Santo Domingo they plotted new attacks against the Lavalas government and its supporters. Chamblain would also later admit, according to El Caribe, a Dominican paper, that “he and other rebel leaders trained a small number of forces in the Dominican Republic.”(41) At one point, a Dominican journalist found that Chamblain, who was working off and on with the FLRN at the time, openly wore a Dominican security uniform with a Dominican Policia National insignia.(42)

Chamblain had fled to the Dominican Republic with the return of democracy to Haiti in 1994. He was eventually found guilty in absentia of organizing the assassination of Antoine Izméry, a Haitian of Palestinian descent who was one of the few outspoken businessmen that had openly backed the democratically elected government. Izméry’s younger brother, Georges Izméry, was also murdered by paramilitaries, in 1992.(43) Chamblain had long-standing ties to the CIA and the DIA, and has continued to maintain ties with well-known figures of Haiti’s business community and extreme right wing.(44)

After an extremely brief stint in Ecuador, his old stomping grounds, Philippe returned to the Dominican Republic where he joined forces with a motley group of ex-military and Duvalierist criminals who had also fled justice in Haiti. Philippe proved adept at finding friends among some of the most eccentric, hardcore members of Haiti’s opposition, and in time would join forces with key members of the opposition’s leadership.(45) Gilbert Dragon, one of Philippe’s closest police comrades, was also a former member of the military. A U.S. embassy cable from early 2001 mentions that Dragon had likely stolen the evidence in a criminal case (either to sell it or because of his criminal connections to the suspect).The cable suggests the U.S. embassy’s growing concern about the police force it had formerly nurtured.(46) (…)

The paramilitaries built relations with many important Dominican officials. William Paez Piantini, head of the Haitian Relation Division of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Santo Domingo and an expert on the border region, made Guy Philippe a welcome guest at his home.(49) “I knew all of them [the paramilitaries]. Philippe was a good friend.”(50) Another official in the Dominican Foreign Ministry, a Haitian expatriate, Jean Bertin, the widower of the anti-Lavalas politician Mireille Durocher Bertin, states clearly that one of his main objectives was to expose and help overturn the Aristide government, as “it was a criminal regime.”(51) Bertin, working closely with Piantini and others in the Foreign Ministry, acknowledges that he had also met with some of the former military men. Ramon Alburquerque, a PRD politician and president of the Dominican Senate, adds as well, “Yes, I visited Guy Philippe’s home, sitting down together we all had talks. I know the neighborhood right where it is!”(52) The FLRN, whose members initially dubbed themselves the Armée sans maman (the motherless army), gradually took shape as the ex-police chiefs now lived freely in the Dominican capital, enjoying friendship and support from segments of the country’s political establishment.

Other Dominican officials acknowledged working with the paramilitaries as well, such as Dr. Luis Ventura Sanchez, financial and administrative manager for the National Council of Frontiers at the office of the Dominican government’s Secretary of State of Foreign Relations.(53) Sanchez, a confidant of Piantini and Jean Bertin, is one of many career bureaucrats within the Dominican Foreign Ministry who are not political appointees but have continued on under different Dominican administrations. In this way the ability for right-wing paramilitary elite networks to operate unhindered by (and at times in league with) state officials, became a phenomenon embedded within the Dominican state.

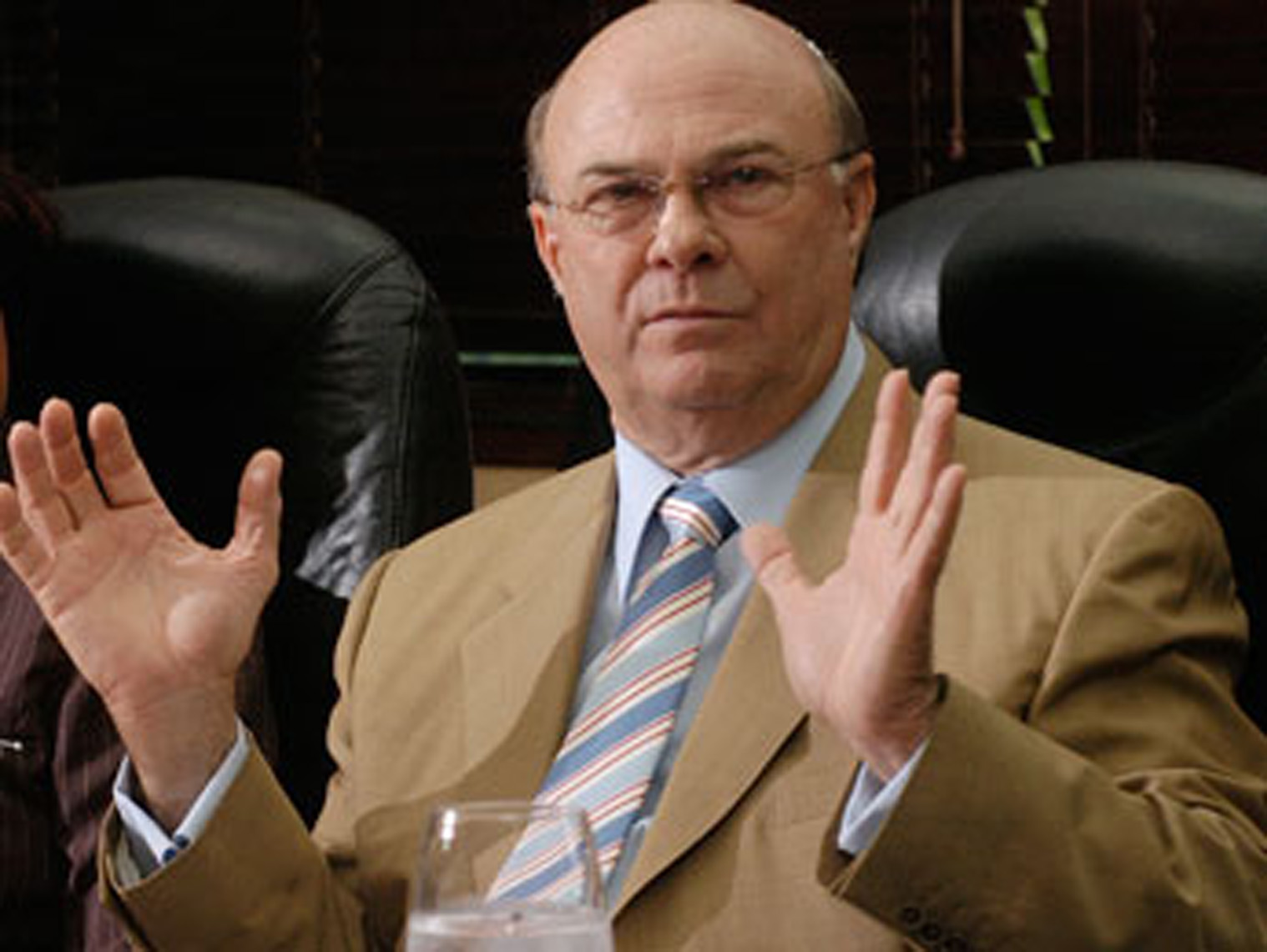

But how far up the Dominican chain of command did support for the FLRN go? Officials at the Dominican Foreign Ministry readily acknowledged to the author that a group within the Dominican military played a prominent role. Though with an obvious political bone to pick, spokesman for Dominican president Leonel Fernández, [former president Hipolito] Mejía’s successor, claimed that Guy Philippe had an agreement with Mejía, who “believed that Aristide was a communist who controlled much of the drug trafficking between the two countries.”(54) Mejía and his top Haiti advisor, Miguel Faruk, denied that the PRD administration ever provided support to the FLRN. However, Mejía acknowledges meeting with many of the Haitian leaders that Delise Herasme, a childhood friend (and controversial Dominican journalist), introduced to him “to improve Haitian-Dominican relations,” a laughable claim given how widely feared and despised some of these people were in Haiti.(55) Mejía claims that in “no way did the [Dominican] military under my administration work with these people” and – even more outlandishly – that throughout his administration “they [the paramilitaries] were never utilizing our territory.”(56)

Hugo Tolentino, a respected senior statesmen of the PRD and the first foreign minister of Mejía’s government, offers a much more plausible version of events: “It appears that President Mejía supported the paramilitaries early on.”(57) Under his supervision the Dominican embassy in Quito provided Philippe and some of his lieutenants safe haven after initially being carted off to Ecuador in 2001. But “it had to have been Mejía who ordered over my head for Philippe to be allowed to return [to the Dominican Republic]. Philippe had friends in high places in the government, you know.”(58) (…)

Dominican journalist Delis Herasme, who has had close ties to Mejía, also claims that Mejía had given the “go-ahead” for paramilitaries to operate in the country. Just as the Haitian paramilitaries were launching their most daring coup attempt in December 2001, Gaceta Oficial reported that under order No. 151-01 the Dominican government was “appointing Mr. Delis Herasme Olivero, Civil Assistant to the President of the Republic.”(63) By 2010, Herasme was identified in the Dominican media as a “leader” of Mejía’s PRD party.(64) Mejía acknowledges that Herasme brought “many businessmen and members of [Haiti’s] opposition” to meet with him while he was president.(65) Haitian death squad commander Louis Jodel Chamblain told me that Herasme was a friend and an important contact inside Dominican society, introducing the paramilitaries to important people.(66)

Herasme bragged to me in 2006 that he had insider information: “I know all of the politicians and military commanders that were involved. They were giving support early on to the 2001 coup [attempt]. Mejía did not object. But by 2004 he was too busy in his reelection campaign to give it attention.”(67) Herasme says that a gathering he hosted in his Santo Domingo home for the paramilitaries was also attended by officials from the Dominican Republic’s two most powerful political parties, the PRD and the PLD.(68)

Years later, a human rights delegation headed by former U.S. attorney general Ramsey Clark, Dr. Luis Barrios, a professor and Episcopal priest based in New York City, attorney Brian Concannon, and former U.S. Special Forces sergeant Stan Goff, investigating the activities of the paramilitaries in the Dominican Republic, turned up other interesting information as well. The group explained how it had received a “countless number of reports” that the FLRN paramilitaries had trained and armed themselves at or near Dominican military bases. Barrios: “President Mejía told a journalist we spoke with that ‘Guy Philippe is under my control. . . . ’ We have received many reports that this operation was used to train Haitian rebels.”(69)

The delegation learned that the paramilitaries had received training near San Isidro, on the outskirts of the country’s capital (and the location of the Dominican Republic’s main air force base); in Neiba, in the western province of Baoruco; in Haina, a city in the province of San Cristóbal directly to the west of the capital; and in the town of Hatillo, which is located in the north of the country in the province of Monte Cristi.(70) A Dominican narcotics investigator, wishing to remain anonymous, partially backed up the investigation’s findings, saying that the paramilitaries, with the approval of Mejía, trained in both Constanza and San Cristobal.(71)

Dominican General Nobles Espejo has similarly come forward, claiming that a sector within the Dominican military was directly backing the FLRN. After interviewing Espejo, Stan Goff concluded:

According to Espejo, a military base not too far from the border, called Constanza, was normally home to a battalion of what they call Castadores, which is like “Rangers” or “Shock Infantry.” One battalion was stationed here. At one point in the year 2000, they amplified that; they transferred two additional battalions of Castadores over to Constanza. They did this because the people of the town of Constanza already knew the people that were assigned there. Any new faces would stand out, but by bringing in two additional battalions from other bases into Constanza, they overwhelmed the community with a bunch of new soldiers and mixed in with those soldiers were the Haitian paramilitaries, who were wearing Dominican uniforms, integrated into the Dominican units, and receiving training with the Dominican military.(72) (…)

The St. Petersburg Times made a similar observation that paramilitaries enjoyed the “tacit support” of the Dominican military, as “some Dominican generals were worried about their own job security.”(79) With no Haitian military, Dominican nationalists could not justify their country’s inflated military spending. “Calls were growing in Santo Domingo to slash the size of their own notoriously bloated and corrupt armed forces. The Dominican generals believed that recreating the old military threat next door would boost their relevance.”(80) At the very least, it is clear that throughout 2001, 2002, and 2003 powerful authorities within the Dominican Republic gave shelter to the paramilitaries even as they carried out cross-border assaults into Haiti. Philippe claims that the Dominicans gave no such direct support but rather “adopted and received me when everyone else rejected me.”(81)

Direct ties between United States intelligence and the Pentagon with Haitian paramilitary forces at the turn of the century are blurrier. In recent years the U.S. military has been involved in a number of training exercises in the Dominican Republic – in Sierra Tierra, Yamasá, and allegedly in Barahona.(82)

It was widely reported that 200 members of a U.S. Special forces unit conducted operations in the Dominican Republic in February 2003, under the auspices of Operation Jaded Task. This was conducted in close proximity to the locations where the paramilitaries trained. Stan Goff has questioned why the operation involved such an “unusually large American military task force in a zone from which anti-Aristide guerrillas were carrying out regular attacks against Haitian government facilities. Its happening at that particular time raises some very serious questions.”(83) Roberto Lebrón, of the Dominican Republic’s Direccion Nacional de Control de Drogas (DNCD), an anti-narcotics enforcement unit of the Dominican police, stated that he has had suspicions about what the United States has been up to in the country.(84) (…)

In the closing weeks of 2000, as various segments of the Haitian opposition protested to the media that they had no connection to the coup-plotting police chiefs, some of their top leadership began to meet covertly with the new paramilitary force gathered in Santo Domingo. Guy Philippe said that soon after his initial failed coup d’état against Préval in December 2000, “leaders [of the Democratic Convergence] like Serge Gilles, Himmler Rébu and others came to the Dominican Republic to ask me to help them save the country.”(101) While Himmler Rébu, a former FAd’H colonel, was well placed to build warm relations with the FLRN leadership and help to unite their fractious group, Serge Gilles’s activities appear to have been important for building up ties with Dominican authorities. (…)

Notes

- “The Autopsy of a Failed Coup,” Haïti Progrès.“Listin” is an anglicism based on “listing” without the g that developed out of the first U.S. occupation of the Dominican Republic (1916–24). Thus the title of media outlet Listín Diario.

- According to the BBC and Radio Metropole, the ex-policemen rounded up at the border were Guy Philippe, Mésilor Lemais, Dormévil Jacques Patrick, Noël God Word, and former Superintendent Marie Jude Jean Jacques. BBC monitoring services reported that two other former officers had taken refugee in the Dominican embassy in Port-au-Prince: “Reliable sources told ‘Hoy’ [a Dominican media outlet] that the first two former police officers who will be sent to Ecuador are Fritz Gaspar Goudet and Didier Saide, as they both have relatives in that country. Goudet has a son there, and Saide was married in Ecuador. The relatives’ names were not reported. It was also learned that other former Haitian police officers were trained in Ecuador…. They all crossed the border with legal visas and are currently being safeguarded at a compound of the Armed Forces’ Secretariat.” BBC,“Government to send seven Haitians involved in alleged coup plot to Ecuador,” Oct. 31, 2000. Radio Metropole’s Jean-Michel Kawa reported some of their names slightly differently: “The policemen are Fritz Gaspard, Jr., Jude Jean-Jacques, Sade Didier, Noël Goodwork, Jacques Patrick Dambreville, and [name indistinct], according to information that has not yet been confirmed, but that I have received from reliable sources.” Radio Métropole, “Premier sacks policemen”; BBC, “Dominican Republic will not extradite to Haiti policemen allegedly part of plot,” October 27, 2000.

- The BBC reported that five former Haitian police officers had fled into the Dominican Republic, and that according to Dominican foreign minister Hugo Tolentino, the paramilitaries were “being held at an installation of the Armed Forces’ Secretariat” and were “not under arrest,” as “he believes that this is the best place for them.” The paramilitaries were questioned by Dominican authorities, reported Radio Métropole: “The six were taken to Santo Domingo, where they were questioned by members of the armed forces, specifically by Gen. Manuel Polanco Salvador and [name indistinct],” an employee at the Dominican Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Ibid. During the course of my interviews in Santo Domingo, I spoke with three officials at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs who acknowledged supporting and working closely with Guy Philippe.

- BBC, “Government to send seven Haitians involved in alleged coup plot to Ecuador,” October 31, 2000.

- Ibid.

- Michael Norton, “American Charged in Haiti,” Associated Press, Nov. 3, 2000.

- “El ejército dominicano informó a Aristide sobre los entrenamientos rebeldes en la frontera,” El Caribe, Feb. 28, 2004, available at http://ogm.elcaribe.com.

- Randall Robinson, An Unbroken Agony: Haiti, from Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President (New York Basic Civitas, 2007), 99, 102; Investigation Commission on Haiti, “Provisional Report” (2004).

- Paul Farmer, “Who Removed Aristide?” London Review Bookshop (2004), available at www.lrb.co.uk/v26/n08/farm01_.html.

- “Gangs Control Town as Haiti Crisis Heats Up,” Voice of America News, Feb. 16, 2004, available at http://www.theepochtimes.com/news/4-2-16/19865.html; Allan Nairn, “CIA linked to FRAPH, coup,” Haiti Info (1994); Louis-Jodel Chamblain, interview with author, Port-au-Prince 2007). In early 2011, with the return of Jean-Claude Duvalier, Chamblain immediately headed up the coordination of the former dictator’s personal security.

- See for example my interview with Judie C. Roy, Port-au-Prince (2006).

- Ambassador Brian Dean Curran, U.S. embassy, Port-au-Prince, Cable C97886, Feb. 23, 2001. The cable concludes that “Commissaire Dragon had a particularly unsavory reputation locally.”

- William Piantini, official at the Foreign Ministry of the Dominican Republic, interview with author, Santo Domingo (2007).

- Ibid. Piantini is also the author of a book on the history of Dominican-Haitian relations, Relaciones Dominico-Haitianas: 300 Anos de Historia. He is considered one of the top experts on the border region between the two countries.

- Jean Bertin, interview with author, Santo Domingo (2007).

- Ramon Alburquerque, former president of the Dominican senate, interview with author, Santo Domingo (2007).

- Dr. Luis Ventura Sanchez, interview with author, Santo Domingo (2007). I interviewed Piantini, Bertin, and Sanchez at their offices in the foreign ministry in Santo Domingo in 2007 when Lionel Fernandez was serving his second term as president.

- Narcotics investigator of the Dominican National Police Force, conversation with author (2006). He requested that his name not be published.

- Hipolito Mejía, interview with author, Santo Domingo (2007). I interviewed former president Mejía at one of his homes, 50 minutes from Santo Domingo. The hilltop mansion was heavily guarded by men wearing cowboy hats and toting submachine guns.

- Ibid.

- Hugo Tolentino, former Dominican foreign minister, interview with author, Santo Domingo (2006).

- Ibid.

- “Actos del poder legislativo,” Gaceta Oficial (2001), available at www.cama-radediputados.gov.do/masterlex/mlx/Originales/1B/503/568/56A/10 071 g.doc.

- However, by mid-2011 Delis Herasme had left the PRD and joined the BIS (Bloque Institutional Social Demócrata), a minuscule party led by Jose Francisco Peña Guaba who is the son of the late Jose Francisco Peña Gomez. The BIS split off from the PRD as part of an electoral alliance that supports Leonel Fernández. See “Peña Guaba compromete BISD apoyo aspiraciones presidenciales del MVP,” available at http://presenciadigitalrd.blogspot.com/2011/02/pena-guaba-compromete-bisd-apoyo.html.

- Mejía, interview with author.

- Delis Herasme, Dominican media pundit and political activist, interview with author, Santo Domingo (2006); Louis-Jodel Chamblain, cofounder of FRAPH, the Front pour l’Avancement et le Progrès Haitien,interview with author, Port-au-Prince (2007); Mejía, interview with author.

- Herasme, interview with author.

- Ibid.

- Randall Robinson, An Unbroken Agony: Haiti, from Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President (New York: Basic Civitas Books), 102; Barrios is an associate professor in psychology and ethnic studies at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York, and is also an associate priest at St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Manhattan

- The city of Haina, sometimes dubbed the “Dominican Chernobyl,” is considered one of the ten most polluted locations on the planet according to scientific studies conducted by the UN. Haina has one of the highest lead contaminations in the world, and scientists have found that most of its population carries some level of lead poisoning likely due to the automobile battery recycling smelter that was previously located in the city. See Blacksmith Institute, “Powerpoint of Blacksmith’s Work in Haina,” Blacksmith Institute (2007), available at http://www.blacksmithinstitute .org/haina.html; “New York Councilman to visit ‘Dominican Chernobyl,’ ” Dominican Today (2007), available at http://www.dominicantoday.com/dr/world/2007/7/21/24783/New-York-councilman-to-visit-Dominican-Chernobyl.

- Employee of the Dominican National Police Force, interview with author (2006).

- See Fenton, “The Invasion of Haiti.” I obtained a copy of the tape-recorded interview that Goff carried out with Espejo.

- David Adams, “Anatomy of a ragtag rebellion,” St. Petersburg Times, Apr. 12, 2004, available at www.sptimes.com/2004/04/12/Worldandnation/ Anatomy_of_aragtag_r.shtml.

- Ibid.

- Hallward, “Insurgency and Betrayal.”

- Anthony Fenton, “The Invasion of Haiti: An Interview with Stan Goff,” Znet, 2004, available at http://www.zcommunications.org/the-invasion-of-haiti-by-stan-goff.

- Ibid.

- Roberto Lebrón (Dominican government narco-nvestigator), email to author (2006).

- Peter Hallward, “Insurgency and Betrayal.”