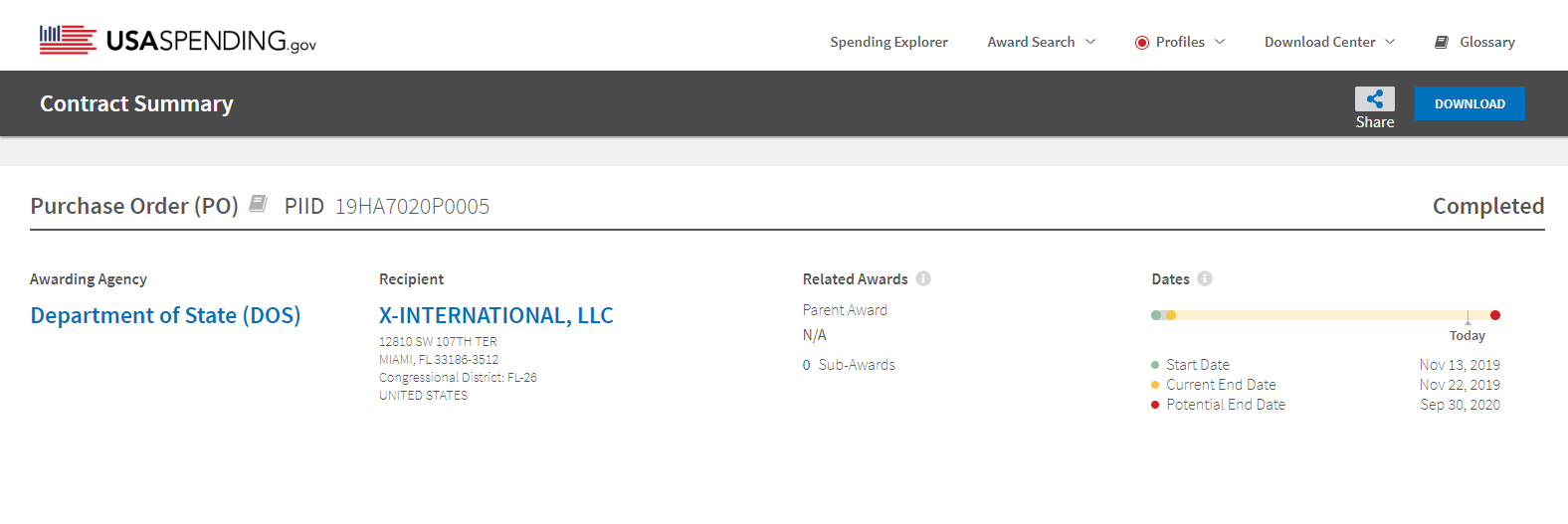

In November, 2019, as part of its support for the Haitian National Police (PNH), the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) awarded a $73,000 contract for the provision of “riot gear kit[s]” for the police’s crowd control unit, CIMO, according to information contained in the U.S. government’s contracting database.

Earlier this summer, CIMO and other PNH units used U.S.-manufactured tear gas to disperse activists who had assembled in front of the Justice Ministry rallying for the right to life amid a rapidly deteriorating security situation. The police repressed the protest even though the organizers had received proper legal clearance. It was an example of why such State Department contracts are concerning — not just because of how the riot gear can be used on the ground, but because of the firm that received the contract: X-International.

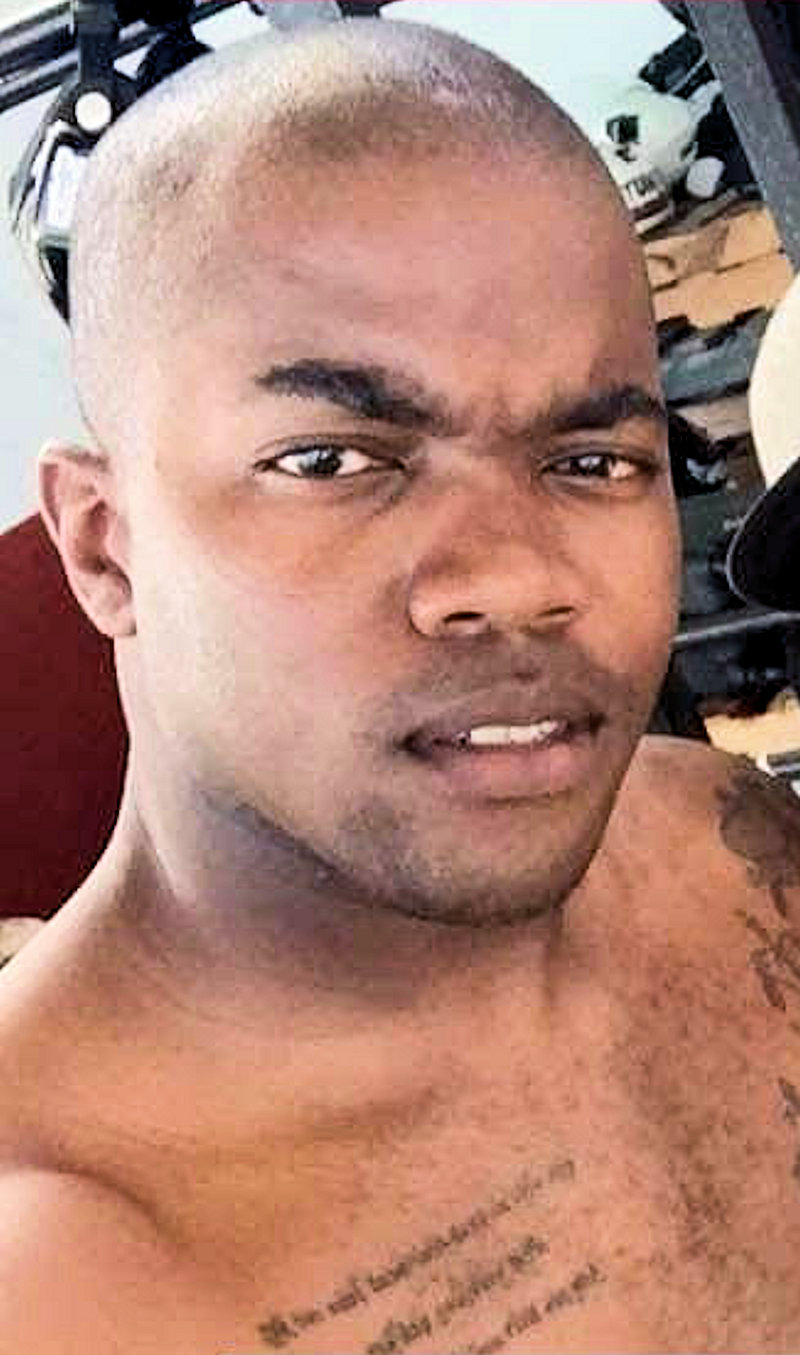

X-International, according to Florida corporate records, is owned by Carl Frédéric Martin, also known as “Kappa.” A Haitian-American and former member of the U.S. Navy, Martin has become increasingly involved in Haiti’s security forces over the last few years, though, his private ventures should raise even more troubling questions about the State Department contract.

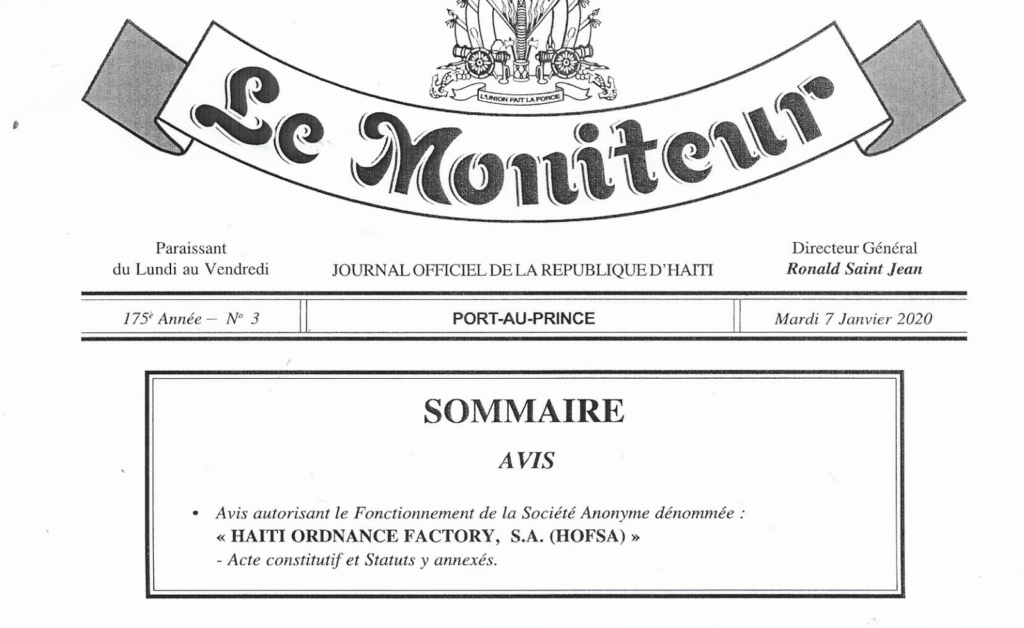

In June, local press reported that Martin, together with a relative of Dimitri Hérard — the head of Haiti’s palace guard — had formed a new company, Haiti Ordnance Factory S.A. (HOFSA). According to its corporate registration documents, the new company would be authorized to manufacture weapons and ammunition in Haiti. After news of the company’s existence broke, however, the government revoked its business license. But this was just one of Hérard and Martin’s new ventures.

In April 2020, before the controversy over HOFSA erupted in public, the two formed another company: Tradex Haiti S.A. Unlike HOFSA, Tradex is not authorized to manufacture weapons or ammunition, but is simply a security company that can buy and sell equipment. Hérard and Martin had been trying to break into the arms market for more than a year. Now, according to a source with knowledge of the industry in Haiti, the two are operating one of the most lucrative arms dealerships in the country.

The arrest of an arms dealer … and an opportunity

In late December 2019, the Haitian government arrested businessman Aby Larco, accusing him of being a significant source of arms trafficking in Haiti. Larco had operated a well-known weapons company for years, with contracts with the PNH and also frequently used by the U.S. embassy to repair firearms. But, prosecutors alleged, he was also an important supplier of black market weapons that wound up in the hands of criminal groups.

After Larco’s arrest, the government’s disarmament commission, created to help get weapons out of the hands of civilians, proclaimed it had a list of criminals who had received weapons from Larco. But more than eight months later, the case against Larco has stalled, and no information has been provided about possibly illegal weapon sales. Meanwhile, Larco’s arrest made space in the Haitian arms market for others to move in.

According to multiple sources close to the case, Hérard and Martin had been in discussion with Larco for many months with an eye to possibly working together. In the end, however, the sources say Larco rejected their overtures. Seven days after his arrest, HOFSA’s corporate registration was published in Le Moniteur. Though President Jovenel Moïse touted Larco’s arrest as a blow against the proliferation of illegal weapons, the government has remained quiet about the head of the palace guard moonlighting as a private arms dealer.

Hérard himself has been implicated in human rights abuses. The State Department’s own 2019 human rights report notes that Hérard “… shot and wounded two civilians in the Delmas 15 area of Port-au-Prince on June 10. Following this incident, several witnesses pursued Hérard’s vehicle toward his residence in Delmas 31. Upon arriving at the residence, Hérard and other PNH officers on the scene opened fire on the group of civilians, resulting in two others being wounded.”

Though Larco’s arrest may have created space for Martin and Hérard to enter the local market, Martin has been an arms dealer for much longer. Among those with knowledge of the local arms market, Martin is known for assembling weapons from disparate parts — in other words, manufacturing weapons that lack serial numbers and cannot be tracked. Some believe it was Martin who provided weapons to U.S. mercenaries arrested in Haiti in 2019. Martin was seen on the streets of the capital embedded with the police during the height of anti-government protests around the same time period. Dozens of protesters were killed, according to local human rights organizations.

Trump Quadruples U.S. Support to the PNH

In a recent report, the National Human Rights Defense Network reported that at least 111 civilians had been killed in gang violence in Cité Soleil in June and July. The December 2019 arrest of Larco, meanwhile, has done little to stem the illegal flow of weapons. In recent weeks, witnesses have seen armed civilians in Cité Soleil carrying automatic weapons that appear to bear the trademark of Carl Martin’s handiwork, raising the possibility that, willingly or not, his guns may be making their way into the hands of civilians. But even as allegations of rights abuses — and police complicity — pile up, the U.S. has deepened its support for the PNH.

Earlier this month, the State Department notified Congress that it was reallocating $8 million from last year’s budget to support the PNH. Since Trump took office, the U.S. has nearly quadrupled its support to Haiti’s police — from $2.8 million in 2016 to more than $12.4 million last year. With the recent reallocation, the figure this year will likely be even higher. U.S. funding for the Haitian police constitutes more than 10 percent of the institution’s overall budget.

The PNH, which recently celebrated its 25th anniversary, has been chronically underfunded, and many officers do not even receive regular paychecks. But, in the current environment, ramped up U.S. support for the police is unlikely to improve the rapidly devolving security situation. Rather, continued diplomatic and financial support from the Trump administration is likely to only harden the corrupt networks that perpetuate insecurity — with potentially deadly political consequences. The State Department award to X-International makes up only a small portion of overall U.S. support to the police, but nevertheless, it is emblematic of the various ways U.S. assistance empowers Haiti’s status quo.

This is a slightly abridged and edited version on an article first published on the Haiti Relief & Reconstruction Watch blog of CEPR.net.