One way to understand Myrlande Constant’s drapo (Vodou flags), presented at Luhring Augustine’s booth in The Art Show at the Park Avenue Armory (November 3-7), is to see them as a sort of riposte to increasing sociopolitical chaos in Port-au-Prince, the Haitian capital where the artist lives. This is all the more pertinent in view of the lawlessness that has reigned in the country for the past few years and contributed to the recent assassination of its president.

Constant is very well known for her unusually large scale, visually arresting figurative takes on traditional drapo, banners stitched with countless glittering beads or sequins and associated with a particular lakou (communal compound). But the exhibit’s guest curator, the abstract artist Tomm El-Saieh, opts for relatively small scale but no less astounding works — and just five of them. This makes for probably the most concise and crisp presentation in an art fair showcasing over 70 “leading” U.S.-based galleries. Thus, one may choose, perhaps, not to see anything untoward about the misspelled names the gallery assigns to her works, especially in view of the fact that it blithely overlooks in two such titles how the artist herself clearly spells the referenced mystical beings in her beaded inscriptions.

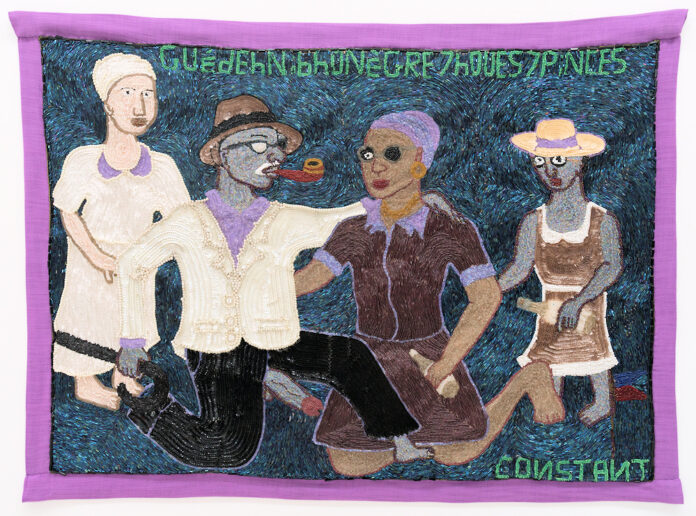

In the earliest drapo in the exhibit, “Ghuede,” [sic] (2003), Constant arrays two centrally kneeling gede figures flanked and overlooked by two stolid female associates. (A gede – the correct Kreyòl spelling – is one among a multitude of often humorously bawdy spirit-like entities who, aside from their pronounced disdain for all manners of human hypocrisy and, especially, prudishness, sees through both life and death.) Aside from being associated with gravedigger and cemeteries, gede spirits affirm procreation, a fact unabashedly stressed here by the pipe-smoking kneeling male seen in full but composed trance and symbolically exhibiting an erect penis. Though the work represents a dramatic instance of possession, Constant maintains a strict distance from mere prurience and sensationalism. It’s more a paradigm for self-possession, a heuristic affirmation of an ethos that is as abstract and mystical as it is socially pertinent.

Yet, as in her four other drapo, it’s the way that Constant technically maneuvers through the formal and symbolic elements of her work that inflects and drives home their meanings. For instance, the all-over, subtly glistening dark-blue background swirls that envelop the four figures in the so-called “Ghuede,” (“Guédeh,” in the artist’s own peculiar spelling), seem almost to erase the blue band of a small Haitian flag planted at the bottom right corner of the piece. At first glance, this inadvertent partial erasure induces one to conflate the red head of gede’s penis with the Haitian flag’s lower red band. Given that the celebration of the gede takes place in November and has long been de rigueur in Haiti’s more popular quarters and, increasingly, in its diaspora (a fact that presumably didn’t escape the show’s Haitian-born curator), this conflation speaks of an evident wish for the Haitian nation to hue more closely to gede’s tenets.

Two other pieces underscore gede’s topical relevance, the graphically tactile “Baron Lacroix” (2010) (“Baron Lacois,” in Constant’s inscription), and the forbidding “Baron Crimenel” [sic]. “Baron” (as in Bawon Lakwa in Kreyòl, not “Lacois”) is of course a rank title borrowed from French traditions to denote a number of gede potentates. Bawon Samdi is generally understood to be the supreme lwa (spirit or spiritual principle) of the underworld. In “Baron Lacroix,” the gede possessing the cross-carrying female rakishly flaunts his vaunted double vision through upside down sunglasses. But, beset by myriad, almost brail-like symbols, the figure’s bearing also conveys a plea for a more heartfelt and temperate sort of Vodou.

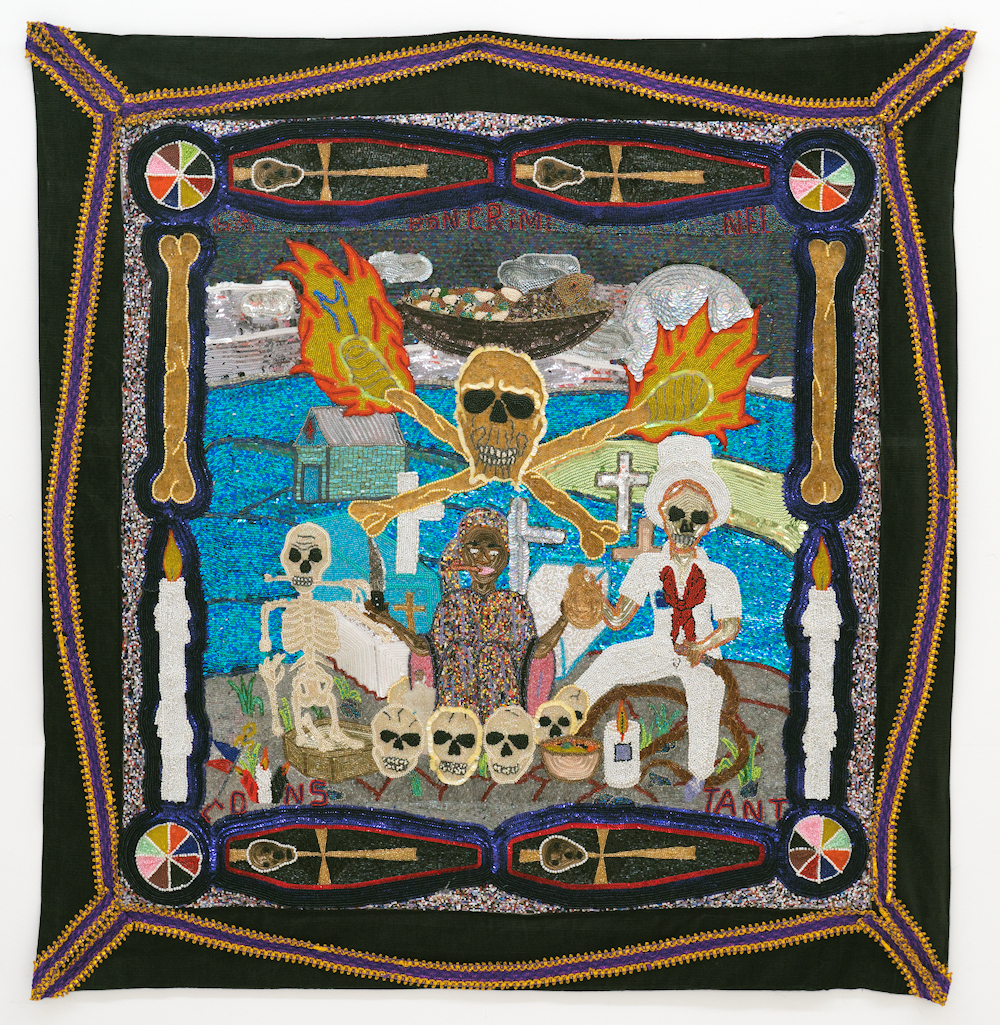

In contrast, in “Baron Criminel” (“Kriminèl” in Kreyòl), Constant dispenses with allusions to such moral persuasion. Created in 2021, when Port-au-Prince’s gangs were wreaking havoc, usually on the more dispossessed parts of a populace (who then often try to leave their homeland), Constant apparently deems it fitting to present a potent lesson – or warning – to all concerned. Baron Kriminèl is said to be wholly unconcerned with questions of good and evil. He’s the ontological epitome of death — not as an abstraction, but as an existential necessity. His particular purview is the efficient business of inflicting death on human life. The burden of ethical judgment lies strictly on the source requesting his intercession. Much more could be said of this fearsome entity – not least, of Constant’s rendering of him as an implacable trinity imbued with different sinister skills and power that she symbolically reintegrates in the form of a lurid skull and burning crossbones.

Constant’s artistic and, especially, spiritual persona is in the thick of all this. As in all five drapo, including the three depicting gede, the technical or less dramatic passages also corroborate her deep engagement with her themes. Note, for instance, how through her direct use of the very same bead colors in the contours or linear accents overlaying her inscriptions she unwaveringly establishes an affinity between her boldly stitched signature and the name of the lwa she represents. More specifically, in “Baron Criminel,” she splits the name of this eponymous lwa into would-be syllabic components and then squeezes these under a row of two horizontal coffins on the upper tier of the drapo. And as if to maintain a direct correspondence with or to vicariously partake in Kriminèl’s ineluctable power, after brutally severing the first syllable of her signature so as to insert votive offerings between “Co” and “ns,” she laterally distances this spit syllable from “tant.” Thus rendered, the two diametrically separated syllables of her signature are tantamount to codas to the top inscription “BA-RONCRiMi-NEL.” What’s well exemplified here — or, ironically, reversed, given that Kriminèl’s domain is the underworld – is the Vodou adage, “What’s above (or in the heavens) has its counterparts in what’s below on earth.”

the scene delineated in “Baron Criminel” seems to constitute a singular, self-contained world

In the context of Haitian art, an example of such complex, camouflaged commitment to convey meanings through written inscriptions that simultaneously suggest a deliberate flouting of one’s relative degree of literacy could be detected in the pioneering Hector Hyppolite’s handling of the lettering in a still life painting, in which he transposes Haiti’s national flag emblem into a sort of bouquet. Consisting of a palm tree flanked by bayonets, flags, cannons, etc., the emblem includes the slogan “L’Union Fait La Force,” which the artist arrays at the top of the picture and behind the palm tree, instead of in its usually lower or foreground position. Moreover, in the work, which was shown in the artist’s 2009 retrospective in Washington D.C., Hyppolite (1994-1948) splits the normally unified scroll on which the slogan appears in two separate pieces. He then saps the vigor in “Fait La Force” by abutting the words in an ungainly, disproportionate configuration — “FAiTLAFORce”: For lack of space in the forked tail end of the scroll, he squeezes in for the last two letters in “Force” a minuscule ‘ce.’

In contrast to Constant, however, rather than wholeheartedly aligning himself behind the theme being illustrated, this self-thought artist consciously or unconsciously botched a crucial part of the national emblem, as if to telegraph a certain distance from the slogan. For, despite the “circa 1948” date assigned to it in the retrospective’s catalog, the painting was most likely done in the earlier part of his brief three-year career (1946-1948) in Port-au-Prince. Indeed, aside from its rudimentary aspects, it was painted on cheap corrugated cardboard — not on cotton or Masonite, materials that the artist arguably could have readily afforded in his glory days. Nevertheless, around 1946, Hyppolite, also a ougan (Vodou priest, roughly) had begun to introduce himself reluctantly in the capital’s effervescent art scene, having been induced by his cosmopolitan benefactors to leave behind the socio-politically ostracized countryside where he had eked out a living by painting and decorating country houses. In short, it was also through his ostensible lack of lettering skills that he marooned himself, as it were, from what may very well have been then, to him, the hollowness of the nationalist project.

“Veve” is an enticingly glinting and expanding universe consisting of what looks somewhat like compacted, tensile gears.

Vodou in Haiti, having long been a persecuted belief-system, one might deduce from all this that there is a definite homespun, crypto-aesthetic vocabulary or approach that Constant and Hyppolite tap into to inflect the meanings of their work. But, in “Maitresse Dalia” (2021) (“Maitresse Daïla,” in Constant’s visibly beaded inscription, but “Mètrès Dayila” in Kreyòl), she dallies in great part with a more knowing mode of working. (I’m told by Haitian art consultant and ougan Jean- Daniel Lafontant that aside from being one of the lwa’s that escort Agwe, (lwa and naval captain who rules over the sea), Mètrès Daïla is quite popular in the southern region of Léogâne and Miragoâne. She’s perceived as Anacaona, the Taino princess and leader whom the Spaniards brutally executed in 1503. (Constant is originally from Léogâne.) So, if the perimeter of dangling tassels and drop beads as well as, say, the stark white inner band overlaid with dark-green leafy swirls framing the central scene in “Maitresse Daïla,” the exhibit’s largest work, come across as overdone and garish, it is arguably because their relative roughness and runaway aspects are not in keeping with the pleasingly well articulated, and sensuous passages she appends on this somewhat rigidly symmetrical composition. For instance, the large, shimmering pink heart, the distinctly tactile light-blue shawl on the enthroned Daïla, the crystal vases and cannons, etc. — these are all mostly foolproof in Constant’s handling, reasonably free from the tellingly untoward or would-be accidental touches seen in her lettering or abutting shapes and colors that favorably complicate and generate her meanings.

No such disjunction occurs in the potent, graphically abstract “Veve” (2010), the smallest work in the exhibit. (Veve are ritual diagrams representing lwa and are usually drawn on the ground with flour.) Whereas the scene delineated in “Baron Criminel” seems to constitute a singular, self-contained world, “Veve,” in contrast, is an enticingly glinting and expanding universe consisting of what looks somewhat like compacted, tensile gears. To access this domain, one has to invoke the lwa that the veve symbolically represents — Legba, the keeper of the gates to all worlds and to other lwa. And Constant of course is metaphorically assisting here, below the horizontal axis of the veve, on earth, as it were, by means of the little Haitian flag planted at the left bottom corner of the work. She’s relatively balanced and unbroken: This time, the supplemental “M” of her first name, in the requisite blue and red, crowns the flagpole, and the horizontal bands of the flag, as if prehensile, literally clutches what comes across as a helm — perhaps, that of Agwe’s ship, which is propped up by a blue and red “CONST.”

As an antidote to chaos, Constant and her lwa have charted a spiritual as well as structural direction for her nation.

André Juste

Philmont, NY

11/11/21

All Photos: Madeline Ruckle, © Myrlande Constant; Courtesy of the artist, CENTRAL FINE, Miami, and Luhring Augustine, New York.