“The truth is that there is a war in Haiti,” Haitian National Police (HNP) chief Léon Charles declared on Radio Métropole May 30, 2005. “This is an urban guerrilla war, and it is a situation that urgently needs a solution. We are working with MINUSTAH [the United Nations Mission to Stabilize Haiti] despite misunderstandings so that together we find a solution to these problems.”

Two months later, Léon Charles, a former soldier with the disbanded Armed Forces of Haiti (FAdH), would effectively be fired and exiled as a military attaché to the Haitian Embassy in Washington, DC.

“We have been frustrated with the HNP’s inability to deliver on even the simplest of agreements,” complained Ambassador Foley

His 17-month tenure as HNP chief from March 2004 (after the second coup d’état against President Jean-Bertrand Aristide on Feb. 29) until July 2005 was marked by widespread corruption and deadly repression of a fierce popular resistance movement against the U.S.-backed overthrow and the ensuing foreign military intervention – first by U.S., French, and Canadian soldiers and then by UN troops – that would last for almost 16 years.

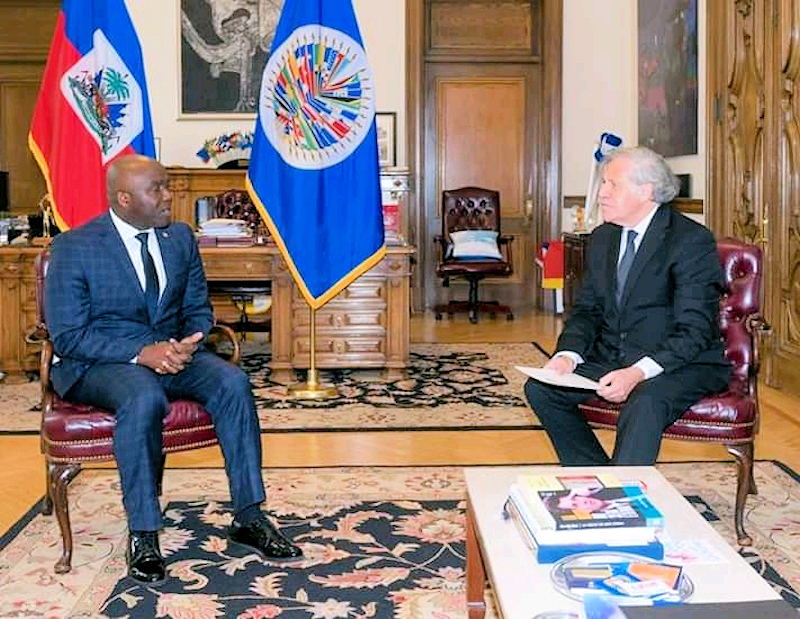

On Nov. 16, 2020, Léon Charles again took the reins at the HNP, after President Jovenel Moïse recalled him from Washington, where he had risen to the post of Alternate Haitian Ambassador to the Organization of American States (OAS). Outgoing chief Normil Rameau had been appointed only 15 months earlier. An HNP chief’s term is usually three years.

Portrait of a Police Chief

When U.S. troops led the first three months of military occupation in Haiti from Mar. 1 until May 31, 2004, they thought they had found their man.

“We have confidence in Mr. Léon Charles,” a certain U.S. Major Richard told Radio Métropole in Kreyòl on Mar. 26, 2004, talking about house-to-house searches for arms that U.S. troops were conducting throughout the capital with the HNP. “This guy is very educated and well-trained; he went to the U.S. Naval Academy in the U.S.. He familiarized himself with the response system that we have in our country. He was very anxious to work with us.”

But a year later, Washington was disenchanted. Five months of secret U.S. Embassy cables from March to July 2005, obtained by the publisher WikiLeaks, provide a candid glimpse into the dealings Charles had with U.S. officials. They reveal a resigned but strained relationship between the police chief and his U.S. handlers.

“We have been equally frustrated with the HNP’s inability to deliver on even the simplest of agreements,” complained Ambassador James Foley in a Jun. 7, 2005 secret cable after meeting with the UN Civilian Police (CIVPOL) force’s Canadian chief, David Beer, who was unhappy with the HNP. “Although Léon Charles remains the best among an uncertain list of alternatives, he is not well served by his deputies and is not entirely in control of the police force.”

“It remains difficult to get the HNP to conduct regular joint patrols with CIVPOL.”

“Clearly frustrated and fatigued,” Beer told Foley that the HNP’s collaboration with CIVPOL was not working. “Beer explained that his plans for HNP deployment along with CIVPOL have been stymied for months. He said CIVPOL had drafted a detailed plan in March for HNP deployment by station and rank up through 2006. Despite professed agreement by the HNP, however, the plan has not been put into practice… It remains difficult to get the HNP to conduct regular joint patrols with CIVPOL. Beer said, for example, that he has insisted that the Crowd Control Unit (CIMO) not be deployed without a CIVPOL escort, but the agreement is often ignored in practice,” resulting in several clashes where HNP officers fatally shot demonstrators (and sometimes vice versa).

Meanwhile, kidnapping was raging in Haiti, and Beer had proposed a “CIVPOL-HNP Joint Command Center (JCC) [which] might help jump-start cooperation with the HNP.” But after CIVPOL spent four months putting the JCC together, the HNP “suddenly scuttled the project” and a similar “special MINUSTAH-HNP Joint Anti-Kidnapping Unit created recently… has already foundered, Beer said. He claimed that after a few days the HNP officers assigned stopped coming and stopped sharing information.”

“Beer suggested that corruption, even in these special units, was endemic and that Charles was unwilling or unable to discipline or arrest officers that everybody knows are corrupt and colluding with the kidnappers,” Foley reported to Washington.

Neutralizing the “Bandits”

But Charles’ biggest chafe with Washington was over how to deal with Cité Soleil and Belair, two of Port-au-Prince’s most rebellious and heavily armed neighborhoods from which the “urban guerrilla war” was being waged by anti-coup, anti-occupation, pro-Aristide popular organizations which U.S. officials called “gangs” or “bandits.”

Charles wanted Washington to give him or allow him to buy more heavy weapons to combat rebels. He also wanted the MINUSTAH and CIVPOL troops, not the HNP, to take the lead in making incursions into Cité Soleil, in particular. He complained that “though MINUSTAH forces were better equipped and trained, MINUSTAH had insisted that the HNP be the first responder and the first to draw fire.”

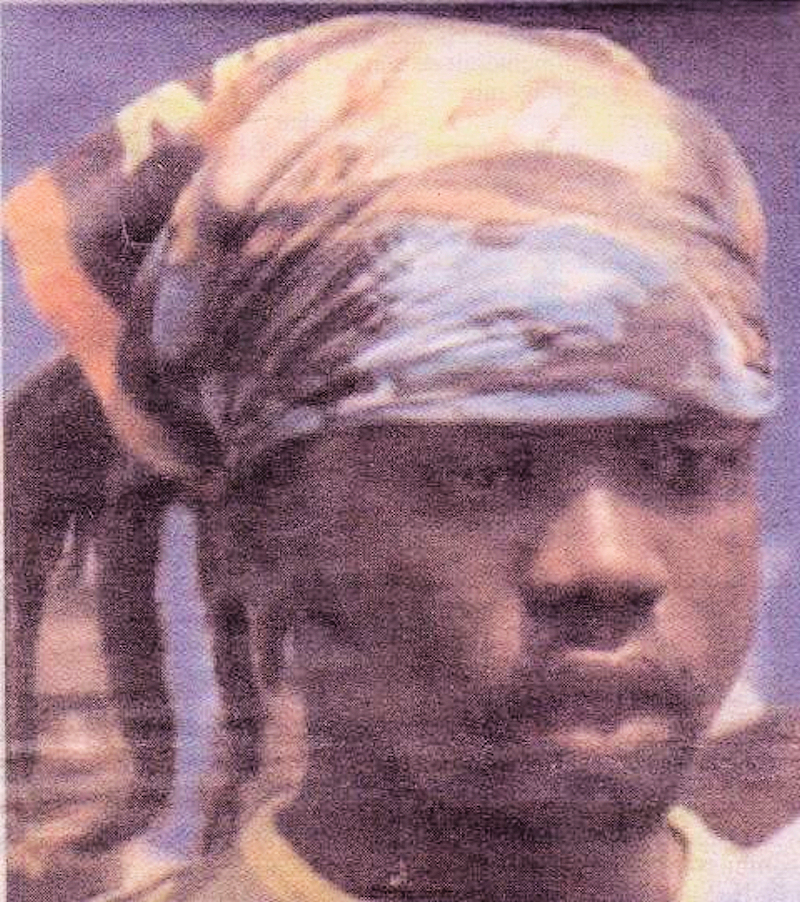

In a Mar. 30, 2005 secret cable, Foley related a Mar. 27 meeting in which “Charles described a joint MINUSTAH/HNP operation in Cite Soleil to control access into and out of the area for two weeks beginning March 31. The mission will establish checkpoints and provide a base for smaller operations inside the dense slum area to try to root out gang leaders, particularly Dred Wilme…”

Emmanuel Wilmer – known as Dred or Dread Wilme – was the most prominent, effective, and militant of popular leaders keeping the MINUSTAH and HNP at bay and out of Cité Soleil.

“Charles also confirmed MINUSTAH, CIVPOL and the HNP have established a special team to target the most wanted individuals,” like Dred Wilme, Foley wrote. “He said Special Intelligence Unit (SIU) Director Michael Lucius was assisting along with ten HNP officers detailed to the team.”

Michael Lucius was himself a questionable character, according to the Embassy. “Despite continuing concerns about his possible involvement in drug-trafficking, Lucius is certainly a more effective manager than his predecessor,” wrote U.S. Chargé d’Affaires Douglas Griffiths in a Jul. 6, 2005 secret cable, referring to Lucius’ recent reappointment (thanks to Charles’ nod) to head the Judicial Police (DCPJ), the #3 HNP post. But while at the SIU, Lucius’ job had been to infiltrate and spy on the rag-tag anti-imperialist resistance germinating in Haiti’s slums.

The Special Intelligence Unit of Léon Charles and Michael Lucius should not be confused with the Special Investigation Unit (also SIU) established by President Aristide “in late 1995 to investigate politically motivated crimes committed before, during, and after the period of military rule” from 1991 to 1994, as profiled in a September 1996 Human Rights Watch report “Thirst for Justice, A Decade of Impunity in Haiti.” Working in conjunction with international human rights lawyers, Aristide’s SIU was launched to investigate 77 murders, massacres, and disappearances from 1988 until 1995 carried out under military regimes, such as the Sep. 11, 1993 broad-daylight execution of democracy activist Antoine Izméry, the Oct. 14, 1993 deadly ambush of Justice Minister Guy Malary, the Apr. 23, 1994 Raboteau massacre, the Aug. 28, 1994 assassination of Father Jean-Marie Vincent, and the Sep. 11, 1988 St. Jean Bosco church massacre.

But Charles’ and Lucius’ SIU had the exact opposite purpose: it was a tool to pave the way for unspeakable human-rights crimes. After multiple deadly raids and skirmishes in Haiti’s shantytowns, the UN and HNP launched a devastating attack against Cité Soleil in the pre-dawn hours of Jul. 6, 2005, dropping grenades from a helicopter in the middle of the crowded shantytown and killing Dred Wilme.

“Acting under intense U.S. and Haitian elite pressure, 1,400 UN troops sealed off the pro-Aristide slum, firing 22,000 rounds and causing dozens of casualties in just one six-hour night-time raid,” explained Dan Coughlin in a Sep. 21, 2011 Haiti Liberté article based on leaked U.S. Embassy cables.

“What we found… when we went into the community the day after the operation was widespread evidence that the troops had carried out a massacre,” explained union and human rights activist Seth Donnelly on Democracy Now. “We found homes, … basically shacks of wood and tin, … riddled with machine gun blasts as well as tank fire. The holes in a lot of these homes were too large just to be bullets. They must have been tank-type shells penetrating the homes. We saw a church and a school completely riddled with machine gun blasts.”

ANI, a New SIN

The SIU, which helped establish such “targeting” in Cité Soleil, is being resurrected today, just as Léon Charles returns to the HNP. On Nov. 26, 2020, President Jovenel Moïse unilaterally decreed the formation of a new “National Intelligence Agency” or ANI. (This year, Moïse has been ruling by decree because he refused to organize elections and allowed Parliament to expire on Jan. 13, 2020.)

The new agency’s mission, announced in an unusually large 24-page edition of the government’s journal of record Le Moniteur, is “to collect and treat information concerning national security… [and] strengthen interior and exterior security… [by] preventing and repressing acts of terrorism and sectarian excesses… [which] undermine state security.”

The 23 clauses outlining the new agency’s mission also point to the ANI’s role “to provide the Head of State [President] a daily report on national security and the protection of the Nation’s fundamental interests.” Constitutionally, oversight of state security is supposed to be done by the Prime Minister (Chief of Government), who heads the Supreme Council of the National Police or CSPN. (President Moïse has already proposed rewriting the Haitian Constitution before new elections, which is illegal with Parliament disbanded.)

Some on social media have called the new agency a Haitian Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). But the final clause decreeing the ANI’s power suggests a more apt comparison: a Haitian Gestapo.

The ANI will “receive and carry out the mandate to investigate for justice, apprehend the persons wanted by the judicial authority, and bring them before the competent authorities.”

the ANI’s power suggests a more apt comparison: a Haitian Gestapo.

In short, this secret agency’s completely anonymous officers (Article 43) will have false identities (Article 44), carry guns (Article 51), be legally untouchable (Article 49), and have the power not just to spy and infiltrate but to arrest anybody engaged in “subversive” acts (Article 29) or threatening “state security” i.e. the power of President Jovenel Moïse. A similar role was played by the Duvalier regime’s Volunteers for National Security (VSN), popularly known as the Tonton Macoutes, an internationally infamous paramilitary force.

“They are putting in place the infrastructure to track, repress, and intimidate the huge demonstrations and outcry that are already building against Jovenel’s plan to remain in power beyond Feb. 7, 2021, the date the Constitution says he must step down,” said Berthony Dupont, the director of Haiti Liberté. “The completely illegal ANI will be one more weapon to beat back the opposition and popular movement clamoring for Jovenel’s departure.”

In the same issue of Le Moniteur containing the 19-page ANI decree, there is a five-page decree “for strengthening public security” which orders that people convicted of “terrorism” will be jailed for 30 to 50 years and pay a fine of 2 million to 200 million Haitian gourdes ($28,797 to $2,879,706).

“With the decrees for establishing ANI and strengthening public security, the regime has let all pretense drop and made its project clear,” said lawyer Jaccéus Joseph, the director of the Office of Human Rights Defense Organizations (BODDH). “They are preparing to reestablish the same Duvalierist Macoute dictatorship which ruled Haiti from 1957 to 1986, which gave itself the power to violate human rights, assassinate people, barge into their homes, kidnap them, and trample all laws and rights enshrined in the Constitution, including that of habeas corpus and the right to a fair trial.”

Perhaps the most direct inspiration for the ANI was the National Intelligence Service (SIN), formed and funded with up to $1 million yearly by the CIA after the 1986 overthrow of Jean-Claude Duvalier, at the peak of the anti-Duvalierist movement which drove the dictator from power. Run by FAdH officers, the SIN “engaged in drug trafficking and political violence,” explained Kathleen Marie Whitney in a 1996 article, “SIN, FRAPH, and the CIA: U.S. Covert Action in Haiti” in the Southwestern Journal of Law and Trade in the Americas. She found that the group produced no intelligence and instead used their training against political opponents.

The SIN Spawns a Death-Squad

The SIN eventually spun off the death-squad known as FRAPH (Revolutionary Front for Haiti’s Advancement and Progress) headed by Emmanuel “Toto” Constant, explained investigative journalist Allan Nairn in an Oct. 24, 1994 article “Behind Haiti’s Paramilitaries” in The Nation.

Col. Patrick Collins, the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) attaché in Haiti, first approached Constant while he “was teaching a training course at the headquarters of the CIA-run National Intelligence Service (SIN) and building a computer database for Haiti’s notorious rural Section Chiefs at the Bureau of Information and Coordination in the General Headquarters of the Haitian coup regime,” Nairn explained. “Constant said that Collins began pushing him to organize a front ‘that could balance the Aristide movement’ and do ‘intelligence’ work against it. He said that their discussions had begun soon after Aristide fell in September 1991. They resulted in Constant forming what later evolved into the FRAPH, a group that was known initially as the Haitian Resistance League.”

The FRAPH would later significantly contribute to the murder, massacre, rape, and disappearances of about 5,000 Haitians during the military coup that lasted from 1991 to 1994. Meanwhile, according to Whitney, the SIN itself murdered up to 5,000 members of democratic movements from 1986 to 1991.

“Using secret intelligence agencies to defend a constitutional republic is akin to the ancient medical practice of employing leeches to take blood from feverish patients,” said Morton Halperin, who acted as U.S. President Bill Clinton’s National Security advisor. “Secret intelligence agencies are designed to act routinely in ways that violate the laws or standards of society.”

The CIA supported the SIN until after the first coup on Sep. 30, 1991 against President Aristide.

“Toto” Constant, who was deported from the U.S. to Haiti on Jun. 23, 2020, is presumably still jailed in Haiti after spending 12 years in a U.S. jail for mortgage fraud. He was convicted in absentia of involvement in the 1994 Raboteau Massacre but now can request a retrial. The increasingly authoritarian moves by Jovenel Moïse and his political affinities with Léon Jeune make Constant’s release – and even pardon – still possible.

Embassy Questions Charles’ Capacity

Under Léon Charles in 2004 and 2005, the Haitian police became a virtual private army of Haiti’s bourgeoisie, which provided officers with weapons and money. Also, Justice Minister Bernard Gousse was “circumventing [CIVPOL commander] Beer’s controls” and sending out police units “on his direct order,” the cables explain.

Fearful that it was losing control of the police, the U.S. Embassy questioned Charles about the matter, as Ambassador Foley detailed in an Apr. 5, 2005 secret cable.

Léon Charles “flatly denied rumors that the IGOH [interim government of Haiti] was creating a separate fighting force, saying there were no plans he was aware of to create a ‘military police’ of any kind.”

Nonetheless, the U.S. Embassy was beginning to doubt Charles’ honesty and capacity to control the police when he was unable to account for weapons, had more salaries than police officers on his payroll, seemed prone to favoring fellow ex-FAdH soldiers’ integration into the HNP, and explained away repeated police killings of anti-coup demonstrators in Belair and Cité Soleil.

“The fleeting reply to requests for updates on human rights investigations demonstrate the HNP’s inability to perform internal investigations,” Foley summarized.

Léon Charles may take a similarly disingenuous approach if questioned about the formation and future conduct of the ANI, with which he will have to closely work.

“Version of Events” Challenged in 2020 and 2005

On the morning of Dec. 4, 2020, the HNP carried out its first major operation under Léon Charles’ new command, intervening in the Port-au-Prince neighborhood of God’s Village (Village de Dieu), a bleak, impoverished sea-side community which has been controlled by an armed group known as the Five Seconds Base for years. It has been a police no-go zone.

But heavily armed and armored HNP officers entered with tanks, explosives, and tear-gas. At a press conference later that day, Charles proclaimed the operation a success.

It fit his profile not only to make a show of force in Village de Dieu, just as he did in Belair and Cité Soleil 15 years ago, but also that his account of events would be contradicted by others.

Charles claimed that the HNP had regained control of the neighborhood, but the leader of Five Seconds, known as Izo, immediately took to Facebook to deny the account, saying his group had suffered no casualties and retained control of Village de Dieu.

Wherever the truth lies, the U.S. Embassy was also leery of Charles’ reports 15 years ago, as made clear in a May 6, 2005 secret cable by Deputy Chief of Mission Douglass Griffiths about police fatally shooting at least five people on Apr. 27, 2005.

“April 27 was the fourth occasion since February where the HNP used deadly force,” Griffiths reported. “Despite repeated requests, we have yet to see any objective written reports from the HNP that sufficiently articulate the grounds for using deadly force. Equally disturbing are HNP first-hand reports from the scene of these events. These are often confusing and irrational and fail to meet minimum police reporting requirements. The HNP continues to suffer from corruption among its ranks, a broken system of justice, substandard command and supervisory control, inadequate levels of training, and scant equipment resources.”

According to Charles’ “version of events” delivered to a high ranking State Department official on Apr. 29, an “unauthorized march left Bel Air around 11:00 a.m. and circled around the Presidential Palace before returning back to the Bel Air area and then proceeding on Delmas toward Bourdon (and the area around UNDP/MINUSTAH headquarters).” Demonstrators don’t need authorization to protest in Haiti but simply must notify police in advance of any planned demonstration.

“The police gave chase and opened fire on the fleeing suspects.”

According to Charles, “as the march neared Bourdon, hundreds of people crowded the streets and brought vehicular traffic to a standstill,” Griffiths continued. There was a mélée, and “police, monitoring the demonstration, heard several shots and witnessed a group of ten young men running in Bourdon near MINUSTAH Headquarters. The police gave chase and opened fire on the fleeing suspects. Several of the suspects were apprehended and two were shot and killed by the pursuing HNP units. Three other suspects were also shot and killed by the HNP, but it was not yet clear if they came from the same group that the police initially encountered. One 9mm pistol was recovered by the HNP not far from the deceased suspects.”

Charles told a different story when he spoke to the Embassy 10 days later, on May 9, Griffiths wrote in his May 13, 2005 secret cable.

“Charles… gave an updated recount of the incident on April 27 during which four people were killed in the vicinity of a pro-Lavalas demonstration near MINUSTAH headquarters… He said that CIMO units were not involved in the shooting. Instead, regular police officers from the Canapé Vert and Port-au-Prince stations were pursuing two groups of bandits in the area. Police exchanged gunfire with one group that had been attacking pedestrians and vehicles near the demonstration, resulting in the deaths of two suspected bandits, while simultaneously another police unit confronted a truck carrying a group that had fired at the Hotel Christopher [which doubled as UN headquarters], killing another two suspects. Charles said that both incidents occurred after the demonstration had already finished. CDA Griffiths stressed that it was important to issue a complete report of the incident. He noted that in the United States police officers were generally moved to desk jobs after being involved in a shooting, pending an investigation.”

Broadcast reports on Radio Solidarité and Radio Ginen, among others, completely contradicted both of Léon Charles’ reports to the U.S. Embassy. According to multiple witnesses, journalists, and even the principal organizer of the march, prominent activist Jean-Baptiste Jean-Philippe, known as “Samba Boukman” (assassinated in March 2012), the Haitian police fired unprovoked on peaceful demonstrators who were demanding the liberation of political prisoners, an end to political persecution, and the physical return of President Aristide to Haiti from exile in South Africa.

Well-known journalist Guyler C. Delva gave an on-the-scene report that “thousands and thousands of demonstrators” were still demonstrating when the police began shooting, killing five, and wounding many others, including several schoolchildren.

“The demonstration had arrived at Bourdon, and, according to witnesses, the police opened fire on the demonstrators,” Delva reported. “I spoke to a policeman who said there had been gunfire [from the demonstrators] and that they found a gun on a demonstrator. But others living in the area and marching in the demonstration said that is not at all true. There were no demonstrators who fired weapons. It was an entirely peaceful demonstration, according to the witnesses I spoke to.”

Delva then played an interview with Dorisma Ronel, 21, who was wounded by the cops. He also denied there had been any shots from the crowd.

Delva then described the men who had been killed. “There were three who all had died in the same place, there was another who fell about five or six meters away from them, and then there was another who was apparently running away and they killed him on the top of a hill. All five bodies are presently in the morgue.”

Meanwhile, Radio Ginen interviewed two schoolchildren, James Joseph and Clédanor Vania, who were wounded, and a third person, the same Dorisma Ronel, who was not in the protest but returning from the pharmacy when he was shot in the foot.

“We deplore and condemn the massacre the HNP committed against demonstrators on Apr. 27, 2005,” Samba Boukman declared on Radio Ginen. “We see that despite all our efforts to have the population trust the police, that does not prevent the HNP from continuing their summary executions of the population… It was the general direction of the police which ordered it.” Samba Boukman asserted that on Mon., Apr. 25, 2005, his messenger Joseph Roudy was harassed in police headquarters as he gave the letter notifying the police about the Apr. 27, 2005 demonstration.

In short, Samba Boukman and the many witnesses that day gave testimony that differed dramatically from Léon Charles’ account.

Trump vs. Biden Policies

Charles record from 2004 and 2005 may come back to haunt him. As Jake Johnston and Kira Paulemon note in a Nov. 30, 2020 article on the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) site: “Working with UN troops after the 2004 coup, the Haitian police were involved in a widespread, iron-fisted, and politically-motivated crackdown in Haiti’s capital that left thousands dead. As police chief, Charles also oversaw the reincorporation of former members of the military into the force despite questions over human rights vetting. Further, a human rights report from the University of Miami found that Charles ‘routinely [gave] orders to stop political demonstrations, and the police [did not] hesitate to perform for him.’”

Charles conduct during his decade and a half in Washington also does not suggest he’s become any tougher on corruption, for one thing.

In addition to acting as Haiti’s Alternate Ambassador to the OAS, Charles was also drawing a salary as the head of the Mixed Haitiano-Dominican Commission. The holding of two jobs is a violation of Haitian Foreign Ministry rules and ethics, a veteran Haitian diplomat told Haïti Liberté.

The State Department of President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo appeared to give President Jovenel Moïse a carte blanche in his illegal, corrupt, and repressive policies. However, the incoming administration of President Joseph Biden may reestablish after its Jan. 20, 2021 inauguration some of the neoliberal oversight guidelines and “redlines” evidenced in the WikiLeaked cables, to better control and justify support for patently corrupt authoritarians like Moïse.

If the new U.S. administration does try to reestablish some minimum of “decorum” to the out-of-control Haitian state, it may have implications for Léon Charles in his new job.

“The regime needed a guy who had a proven record of ruthlessly repressing the masses in the popular neighborhoods so they can stop the mass mobilization which is starting here,” Jaccéus explained. “He killed many, many people in the popular quarters when he was police chief in 2004 and 2005. He won’t hesitate to unleash the police on the masses and Jovenel’s political opposition again. He shares the regime’s ideological position: he is basically a Duvalierist, a Macoute. He has no problem with the dictatorship that the new decrees are announcing. This will all become very clear as Feb. 7, 2021 approaches.”

[…] https://haitiliberte.com/loyal-to-washington-new-police-chief-leon-charles-specializes-in-counter-in… […]