The United States under enslaver president Thomas Jefferson imposed a blockade of Haiti in 1806, which lasted until 1862. This was the first of a multitude of sanctions the U.S. has imposed on Haiti, which have hindered, distorted, and delayed its economic development.

Haiti’s historic lack of economic independence and development is the root cause of its current hunger crisis, in which, according to the United Nations World Food Program: “A record 4.9 million people are projected to be in acute hunger (Integrated Food Security Phase Classification 3 and above) in Haiti — that’s nearly half the country, including 1.8 million people in ‘emergency’ phase (IPC4).”

A woman from Cité Soleil, a Port-au-Prince neighborhood of 100,000 people considered the poorest neighborhood in Haiti, told the World Food Program what being in phase IPC4 meant to her personally: “Look at my belly; I haven’t eaten for two days,” she told WFP staff at an emergency food distribution in Cité Soleil.

Haiti, according to the WFP, depends on imports for half the food and 80% of the rice it consumes, making food prices in Haiti highly impacted by worldwide inflation. A series of natural disasters over the past two decades — severe storms, floods, landslides, drought, the devastating 2010 earthquake, the Category 4 Hurricane Matthew in 2016, and an earthquake which devastated the country’s southern regions in August 2021 — have added to Haiti’s misery.

But long before these natural disasters, the U.S. made two major interventions that set back Haiti’s economic development.

Decline of pigs and the pork industry

In 1981, swine fever broke out in Haiti and the Dominican Republic, which share the island of Hispaniola.

(In 2007, a pilot from North Carolina contacted Haïti Liberté alleging that in 1979 and 1980 he had been contracted by the CIA to fly a small single-engine Cessna airplane out of the Port-au-Prince airport to drop pelts infected with swine fever on several occasions over Cuba. The Cubans quickly eradicated the 1980 swine fever outbreak in their country by quarantining the infected pigs, however the virus was inadvertently released in Haiti via the infected pelts, the pilot claimed. Haïti Liberté has not yet been able to confirm the allegation but considers it plausible given the history of the U.S. war on Cuba. – Editor’s Note)

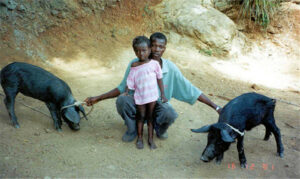

The U.S. Agriculture Department, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the International Development Bank, and the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA) came up with a plan that required Haitian farmers to kill every kochon kreyòl, as the small indigenous black Haitian pigs were called. Haitian farmers got replacement pigs from the U.S. that were not suited to be raised under local conditions — for example, they required concrete pens and special feeds which Haitian farmers could not afford. So the large white imported pigs – known as kochon grimèl – died off, and Haiti’s pork industry collapsed for many years. The kochon kreyòl was thought to have become extinct, but some of the stock survived the early 1980s extermination and, mated with pigs imports from Jamaica and other Caribbean islands, the breed has begun a resurgence. Nonetheless, the Washington-directed slaughter of 1982 and 1983 was yet another major deleterious impact on Haiti’s economic development.

Rice – domestic crop replaced by imports

Rice is a mainstay of the Haitian diet and an integral part of its African heritage. Until the early 1980s, Haiti produced enough rice, primarily in its central Artibonite Valley, that it could feed its own population and have enough left over to export. Under Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier in 1984, and especially after his fall in 1986, the U.S. Agency for International Development pushed a plan to lower the custom duties on rice imports so that U.S.-based firms could compete.

They pushed for food aid to end hunger in Haiti, but this aid flooded Haitian markets, driving Haitian peasants into bankruptcy. However the food aid program was very profitable for the U.S. firms, which produced and transported rice in particular.

Through all the turmoil that followed the “dechoukaj,” or uprooting of Jean-Claude Duvalier, U.S. rice producers from Miami managed to strengthen their hold in Haiti, which then became their fourth largest market. By 2004, rice exports to Haiti amounted to $80 million.

The U.S. political and economic hold on Haiti all but destroyed its rice production and hugely undermined Haiti’s economy.

Workers’ response

It is difficult to organize unions in a country where only 23% of the workers have a steady job (statista.com). Holding mass demonstrations that bring out tens of thousands of protesters into the streets has also become increasingly harder, given the political turmoil growing ever more deadly.

The Taiwanese-owned textile company Everest Apparel Haïti S.A., which is located in the new Caracol industrial park Bill and Hillary Clinton sponsored in northern Haiti, has been attacking the three unions which have organized in their plants.

The unions responded with two go-slow strikes on Mar. 23 and Mar. 28, with notice given to the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (Ministère des Affaires Sociales et du Travail-MAST) to make these slowdowns legal.

An earlier version of this article was published by Workers World.