The gold mines planned for Haiti’s north come on the heels of centuries of foreign investment in – and extraction of – the country’s minerals as well as other natural and agricultural resources.

1492: Writing in his journal during his first voyage, Christopher Columbus said the people of what would later be called “Hispaniola” – today comprised of Haiti and the Dominican Republic – gave the sailors gold with “such generosity of heart and such joy that it was wonderful.” Every other entry has references like “great pieces of gold,” and “pieces of gold as large as the hand.” In the years that followed, hundreds of thousands, some say millions, of indigenous people died in gold mines and due to Spanish-borne diseases.

A decade after Columbus’ first trip, the Spanish crown was already getting its “royal fifth” (20% of all gold found) from the Caribbean, collecting 8,000 ducats (about 884 ounces) in 1503, and about 120,000 ducats (13,272 ounces) in 1518.

1697-1804: The labor of an estimated 800,000 African slaves earned the French colony the nickname “Pearl of the Antilles” because of the massive wealth produced for the French crown and French investors exporting sugar, coffee and indigo. According to some researchers, by 1789 the colony exported one-half the world’s coffee and accounted for about 40% of France’s foreign trade.

1857: U.S. sea captain Peter Duncan proclaimed La Navasse Island, off Haiti’s lower “arm,” a “U.S. territory” under the 1856 U.S. Guano Island Act, which proclaimed that any U.S. citizen could take “peaceable possession” of any guano-rich “island, rock or key” that is “not within the lawful jurisdiction of any other Government.” Guano – bird dung – was in high demand as a fertilizer.

La Navasse was part of Haiti, but no matter. The U.S. claimed the island and a company town was built to “mine” the dung. Today, the company is long gone, but La Navasse is still considered a U.S. territory by Washington. But Haiti still claims La Navasse and lists the island as national territory in its 1987 Constitution.

1910: Hayti Mines Company, based in New York, bought Compagnie Minière de Terre-Neuve. Over 10 years, the company exported 436 tons of copper ore. No more information is available.

1911: W.R. Grace backed U.S. entrepreneur James MacDonald, allowing him to take over Haiti’s National Railroad Company. In exchange for promising to build a railway from Port-au-Prince to the northern city of Cap-Haïtien, MacDonald was given 50-year concessions for all the land alongside the eventual 320-kilometer railway line for banana plantations – two kilometers in each direction – as well as a 50-year monopoly on banana exports. The MacDonald Company issued US$35 million worth of bonds which were 60% guaranteed by the Haitian government. MacDonald failed and fled. During the 1915-1934 U.S. occupation, the Haitian government was forced to pay out over $4 million to investors.

1915-1934: U.S. occupation of Haiti. Explained President Woodrow Wilson in 1913: “Our responsibility to the American people demands that we assist American investors in Haiti.” In 1914, U.S. Marines seized Haiti’s gold reserves, and within months U.S. Marines invaded again to begin the longest of all U.S. military occupations.

After a puppet parliament passed a law allowing foreigners to own land, over 1,000 square kilometers of land were granted to U.S. companies between 1917 and 1927, and another 1,000 square kilometers were sold to U.S. companies after 1928. U.S. pineapple, sugar, banana, and sisal companies expelled tens of thousands of farming families from their plots. Firms included familiar names like United Fruit and Standard Fruit, but also Haitian Products Co., Haitian American Sugar Co., etc. Most U.S. plantations ended in failure.

This period also saw massive migration of Haitian laborers, illegally and legally, to Cuba and the Dominican Republic in search of work. Total numbers are not known but from 1915 to 1930, between 5,000 and 20,000 mostly male labors legally went to Cuba each year.

1935: Standard Fruit and Steamship Company signed a 10-year contract, which was renewed for another five years. The New Orleans-based firm was given a monopoly over all banana exports for the first 10 years, and over most exports for the period 1945-1950. By 1945, in the Artibonite Valley alone, the company controlled 3,900 hectares directly and bought bananas from farmers on another 5,000 hectares. Growers who refused to plant bananas often faced repression and torched fields. Bananas became one of the country’s major exports by 1945, but the corruption of government authorities and other factors contributed to a gradual decline.

1941: The Haitian American Agricultural Development Company (SHADA in French) was formed in order to supply the U.S. government with rubber and sisal (for rope) for World War II. The firm got a US$5 million loan from the U.S. Export-Import Bank and a concession of some 60,000 hectares of farmland and pine forest for the dual purpose of logging and planting rubber and cryptostegia, a rubber bush. In addition, SHADA got over 130,000 hectares of land in the north and northeast, which it logged completely, in order to set up sisal plantations. Farmers thrown off their land received a pittance in compensation – between $5 and $25 per carreau (1.29 hectares). A million fruit trees in Haiti’s southwest alone (Grande Anse) were cut down. In just one year, 1943, over 30,000 families were expelled from their lands.

The rubber project closed down in 1945, with a $6.8 million loss. Other SHADA projects lost over $2 million that year, too. SHADA is considered the worst fiasco “development” project in Haitian history.

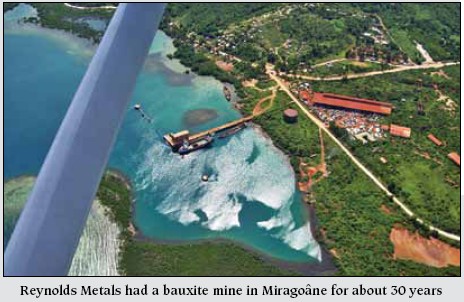

1944: Reynolds Haitian Mines, Inc., obtained an exclusive monopoly on bauxite and a concession to mine near Miragoâne. Over about 40 years,13.3 million tons of bauxite was sent up to Corpus Christi, Texas. Haitian bauxite accounted for almost one-fifth of Reynolds’ bauxite acquisition in the years between 1959 and 1982. Reynolds was given access to 150,000 hectares. Thousands of families were expelled.

1944: Reynolds Haitian Mines, Inc., obtained an exclusive monopoly on bauxite and a concession to mine near Miragoâne. Over about 40 years,13.3 million tons of bauxite was sent up to Corpus Christi, Texas. Haitian bauxite accounted for almost one-fifth of Reynolds’ bauxite acquisition in the years between 1959 and 1982. Reynolds was given access to 150,000 hectares. Thousands of families were expelled.

The Haitian government got royalties of 90 US cents on the metric ton at first, then US$1.29. When Haiti and other countries formed the International Bauxite Association (IBA) in 1974, royalties went up again, but within six years, Reynolds had pulled out, having extracted most of the bauxite and also in search of countries with lower royalties. Over its four decades in Haiti, Reynolds built one eight-mile road and employed about 300 people.

1955: The Société d’Exploitation et de Développement Economique et Naturel (SEDREN), owned by the Canadian company Consolidated Halliwell, obtained a concession to mine copper in the region of Mémé (Terre-Neuve/Gonaïves). Over 12 years (1960-1972), SEDREN exported 1.5 million tons of copper ore valued at about $83.5 million. The government got about US$3 million.

At its high point – 1971 – the mining industry (Reynolds and SEDREN together) employed only 889 people, who were paid only the minimum wage – less than 70 US cents a day at the time. All skilled labor came from overseas.

Haitian economist Fred Doura has called Haiti’s economy a dependent and “extraverted” characterized by enclaves. Speaking of mining, he wrote: “The extractive industry in Haiti is a typical example of an ‘enclave’ industry under foreign domination where two North American transnationals exploited the minerals bauxite and copper… [T]he impact was practically null on the economy.” [Économie d’Haïti – dépendence, crise et développement (2001)]

Sociologist and historian Alex Dupuy agrees with Doura’s assessment. “Historically, foreign investments have not had positive impacts on the Haitian population in general,” the Wesleyan professor explained to HGW in a telephone interview in February 2012. “Usually a few members of the Haitian elite benefit, the state takes its part, and then the profits all go to the company.”

“Peasants have good reason to be distrustful of any and all proposals of foreign investment in Haiti, because they know very well how these projects have gone in the past,” Dupuy added. “They are here to invest for themselves, not for the country, not for the peasants. They appropriate peasants’ lands, taking away their only means of livelihood. So why should peasants trust them, or the central government in Port-au-Prince, or anyone else?”