Emmanuel Merisier produced expressionistic paintings melding European modernist primitivism and the familiar modern variant that his Haitian compatriots have cobbled together for over a century. In his twilight years, he forthrightly reconciled the psychic tensions in his art by tacking preponderantly toward his country’s aesthetic legacy.

Merisier died on Sun., May 3, 2020 at Saint Barnabas Hospital in West Orange, NJ. He was just short of 91 years old. He is survived by a son, Jean Alix, sisters Marie Merisier and Jacqueline Fragé and her children, nephews Eddy Agnant, and Joel Milord and their families. Abel Agnant, another nephew, passed away on Jun. 8, 2020.

Merisier had been in shaky health in the past five years since a stroke left him partially paralyzed. Wheelchair-bound since then, he had been cared for in a nursing home in Orange, NJ. He was transferred from there to Saint Barnabas on Apr. 23 reportedly for breathing difficulties stemming from pneumonia and then tested positive for the coronavirus.

An Art Career Begins

The earliest highlight of his career in New York was probably his 1982 solo exhibition, a gambit for which he spent some $3,000 of his own money to pay for a modest co-op gallery space on West 57th Street, then an art hub with many blue-chip galleries.

To gin up some interest in the art world, he had also placed an ad in Art in America that featured “The Wedding,” his painting of a stolid bride in white and a bestial groom surrounded, as if mockingly, by rara musicians.

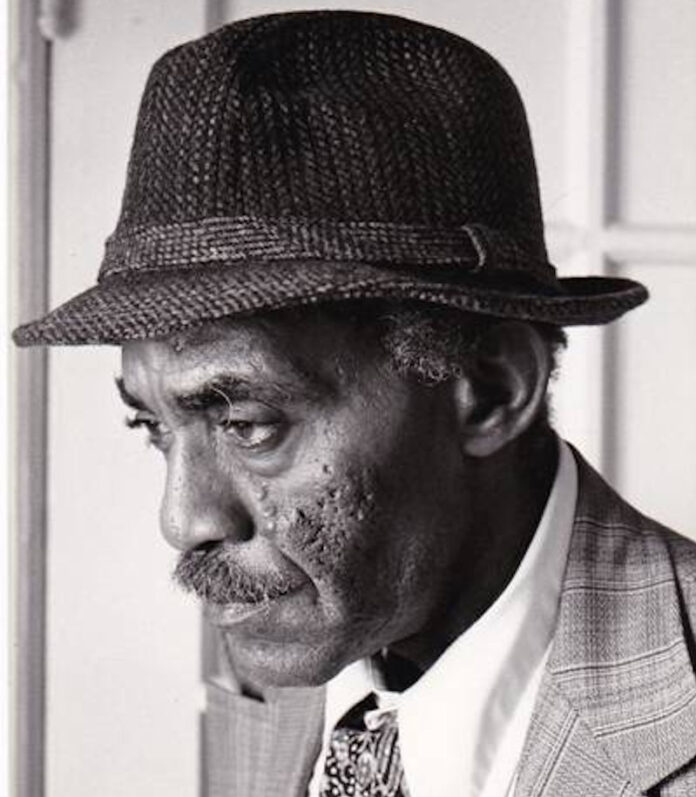

Sporting a polyester blazer, fedora, and often a garish red necktie, he would regularly roam the museums and galleries of Manhattan and beyond

(Merisier reportedly had raised eyebrows for his 1972 wedding to a noticeably older African American pianist named Lucy French. He would walk away from the union’s increasing constraints in about four years, forfeiting much of his possessions but, no small consolation to him, it landed him his green card.)

There were no sales or reviews, but he successfully tested the waters, he related, putting on notice everyone, including all his artist friends – particularly his Sophistiqué peers going back to mid-century Haiti – that he was dead serious in his commitment as an artist.

Time would prove him right – though not necessarily to his art “frienemies” who were wary of his sometimes unbearable indignation about perceived slights and who tended to see his work as too raw and “macabre,” hewing too closely to the would-be technically unsophisticated so-called Primitif art that burst on the fringes of the international art scene in the post-World War II era.

As inconsequential and crass as it could be deemed as an index of his hard-earned accomplishments, however, unlike any other artist of his generation – Sophistiqué or Primitif (including Hervé Télémaque, who from 1957 to 1961 frequented New York City’s then much more openly racist and exclusive art world) – Merisier was probably the only figure who, late in his career, managed to have three solo exhibitions (in addition to about as many significant group shows) in Black-run, art-focused Manhattan galleries. Indeed, pockets of New York City’s so-called mainstream as well as Black- and brown-run art world were his sustenance and refuge when he was away from his stuffy New Jersey apartment-cum-studio, whose decrepitude over time he would ignore and even play up as if to offset his artiste maudit stripes.

Sporting a bland, shrunken-sleeved polyester blazer, fedora, and often a garish red necktie (worn loosely folded at the neck, perhaps not unconsciously, in the manner of Hector Hyppolite in his self-portrait), he would regularly roam the museums and galleries of Manhattan and beyond, snatching up afterwards at The Strand, for instance, some art catalogs or a ponderous, well-illustrated monograph of his favorite European expressionists before trekking back home across the Hudson by train and bus. This, he did in all seasons until about his late seventies, even after hospitalization or, once after a winter fall, with his arm in a sling.

Art Show Politics

With all of his gallery- and museum-going, however, Merisier’s track record is sparse, compared with that of more prominent artists of the African diaspora who have made significant inroad in some of the more vaunted mainstream (usually White-run) art venues. Especially when it’s expedient to the ruling class and its would-be independent custodians of taste, art fashion does change and vary. Unless it’s on some level postmodernist or presented with a telegraphed distance or irony, ostensibly middlebrow and earnest Black, or brown, art that seems couched in well-established conventional or modern styles have been usually shunned – unless, say, its nationalist/Pan-Africanist quotient or implied traditional gender roles could be tempered, objectified, or somehow buffered by historicist considerations. Call it what has been deemed a conspiracy of the highbrow and lowbrow against the middlebrow.

But as slippery and socially determined as these characterizations are, Charles White’s unexpected 2019 retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art – not long ago a preserve for generally white male artists – exemplifies some of this contention. Furthermore, that MOMA, which has had Jacques-Enguerrand Gourgues’ Primitif “Magic Table” in its collection since the late forties, decided – some 70 years later – to hang in its revamped permanent collection an Hector Hyppolite painting of similar vintage (as well as a prescient 1962-1964 work by Télémaque), presents us with a crucial dilemma: Is it salutary meliorism or genuine progress we’re being presented with? Or is it yet another instance of the powers that be spelling out for us once again, through their rarified institutions and assigned gatekeepers, that they themselves, at their own glacial pace, will determine when and under what conditions we will be allowed a voice at the table – or, more precisely, their table. This very same dilemma presently haunts Merisier’s art and career and, therefore, must be teased out and brought to light.

It helped, of course, that there were Black-run or favorable venues in New York City and beyond that were open to Haitian art, and not necessarily as a niche field. Merisier would have significant solo shows at UFA Gallery (Chelsea, New York, 2003), The Selden Rodman Gallery (Ramapo College, NJ, 2004), The Hervé Méhu Gallery (New York, NY, 2007), The Waterloo Center For The Arts (Waterloo, IA, 2013), and The Little Haiti Cultural Complex (Miami, FL, 2018). He also had two other important showings, one at the home of Selden Rodman, the implacable champion and, paradoxically, inimical force against the social evolution of Primitif art (Oakland, NJ, 1994), and the other, at Wilmer Jennings Gallery at Kenkeleba (NY, NY, 2019) for which I was asked – and reservedly agreed – to choose the works and to contribute some writing for only his part of a three-person exhibition doubling as three separate solo shows. (Over the years, Wilmer Jennings/Kenkeleba had a special relationship with Merisier, whose presence at these two galleries stoked their director’s support in the form of exhibitions for many Haitian artists. Portions of Merisier’s paintings are in Kenkeleba’s storage and that of the Toussaint Louverture Foundation.)

Of course, the politics of how artists’ works are presented have a lot to do with how they are considered on many levels, with their overall clout and sales potential and with the degree to which consequential backers or collectors are engaged or vested in the process. (Merisier made two bold attempts to find venues in Haiti that would show his work, traveling there twice, in 1996 and 1997. But the Local Haitian Art Establishment didn’t oblige. That he could come across as alternately pesky, overly sensitive, as well as gratingly boastful about his artistic prowess might not have helped, for instance, when he tried to approach Les Ateliers Jerôme’s director Mireille Jérôme, or the formerly New York- and Port-au-Prince-based dealer Reynald Lally, whose interest in Merisier’s art I tried at least twice to kindle.

Seven Very Different Merisier Shows

Although Merisier’s exhibition at Wilmer Jennings – his last while still alive – was relatively coherent and well presented, viewers there were also presented with the works of Michelle Marcelin and Jean Dominique Volcy. The artists should have had their own separate shows so as to allow more space for a wider range of Merisier’s art to shine by itself in the hope of generating more casual as well as formal discussions about it.

Ironically, the gallery bringing all three artists together in adjacent spaces (after my selecting and writing about only his paintings) under the convenient umbrella title “Passion and Perseverance in Haitian Art” – without bothering in some objective way to actually interface their work, personalities, and backgrounds so as to probe and elicit the presumed cohesive dynamic in their art – merely gratuitously and superficially unites them in their struggles as artists, which is, perhaps, innocuous enough. But it’s usually foregrounded similarities and contrast between specific works, and/or groupings of them, that bring out the particularities and persuasive power of individual artists and, ultimately, their collective strength.

As for Rodman’s private home show, he would acquire from Merisier at least one of the works he showed and subsequently donated it to Ramapo College to supplement his mostly Haitian art collection housed there. Tellingly, as if the exhibition itself was his imprimatur on the artist, he didn’t bother to write a word about the paintings for the show’s opening and duration. So, if the purpose of his home show was not necessarily to shed some light on aspects of Merisier’s work and thinking, might one not be right to see it simply as a fillip to the renown of Rodman’s collection or as another superfluous capping of his great career? Merisier’s works at Ramapo’s Selden Rodman Gallery, although supplemented by a video (which I had helped produce independently about four years before I was apprised of the exhibition) and by an essay of mine (which had been used for the artist’s solo the year before at UFA Gallery), felt attenuated and constrained by all of the Haitian and related works hung salon style in the somewhat cramped space, the smallest among two other much more spacious galleries at Ramapo College.

Moreover, at least one of the artist’s only two or three atypically large-scale paintings – bold, successful statements with which he sought to assert his prowess and to anchor his career – had to be displayed high up above a lobby and isolated from the main part of the exhibition. This in itself diluted the cogency and potency of his presentation and undermined his ambition and avowed profession to be, in his words, a “Primitif Modèn” (or “modernist Primitif”), distinct from both European modernist primitivism and to the art of his Haitian heroes, the first-rate Primitifs. Yet, with his wall-size painting (his largest), Merisier also metaphorically broke out of the mold, as it were, of the Selden Rodman Gallery’s exhibition space, reserved, one might think, for what’s implied to be merely niche or lesser art.

Of Merisier’s few important solo shows, however, the ones at the UFA and Méhu galleries were the most effective in that they were objectively focused, the exhibited works having been chosen, apparently, solely by the gallery director in at least reasonable agreement with the artist. In contrast, the paintings in the Waterloo show had been ostensibly donated by the artist to the museum, provoking an unnerving soupçon of quid pro quo. (To some degree, this was also the case for Hervé Télémaque’s relatively small, and somewhat underproduced retrospective in 2015 at the Centre Pompidou – to which, viewers were told in an introductory wall text, the artist was to donate some additional works).

the wretched being the artist represents comes across as if it were stuck playing a role

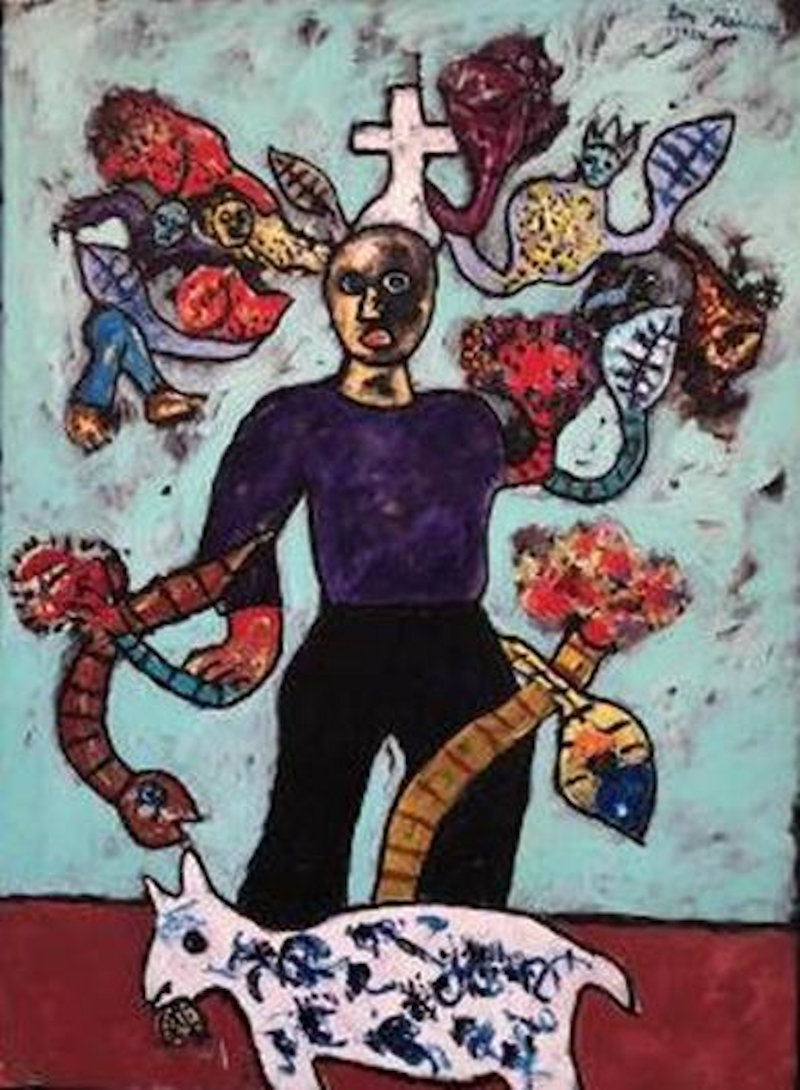

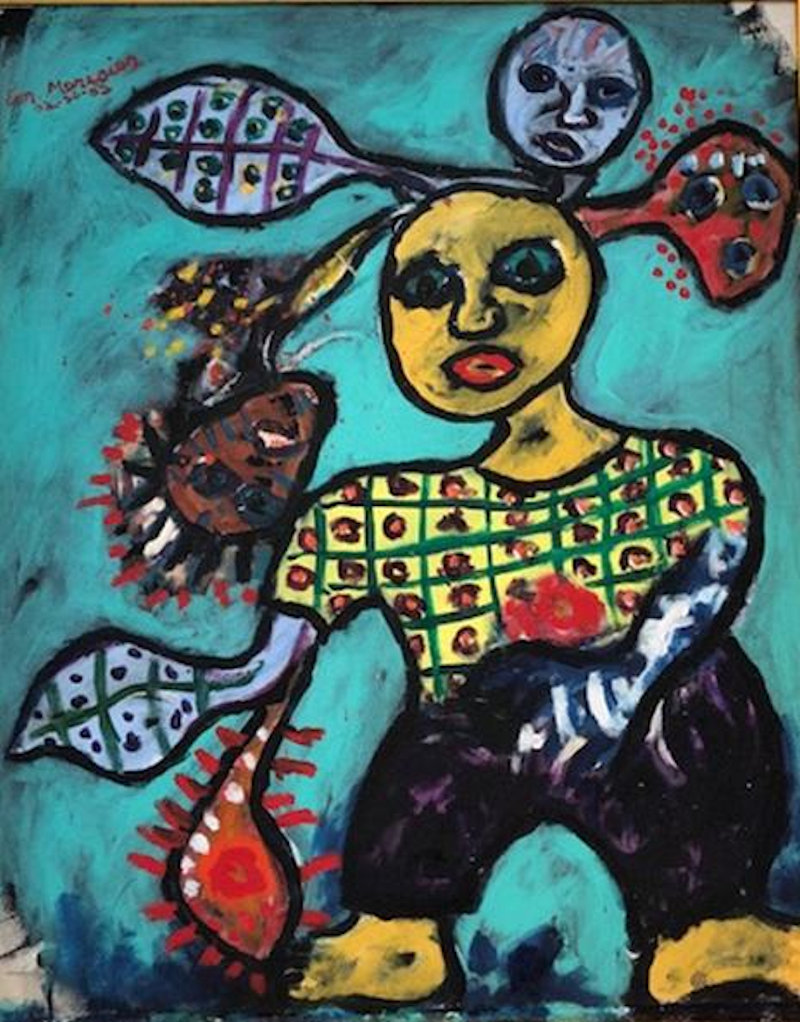

Interestingly, both the UFA and Mehu exhibitions, as in the works I chose for the Wilmer Jennings show, placed a strong emphasis on Merisier’s flat, breakthrough 2000-2002 paintings, with their halting and consistently heavy outlines – characteristics reminiscent of the way vèvè are drawn. (Vèvè are schematic, ritual line drawings made on the ground, often with flour loosed in short discontinuous motion from between forefinger and thumb.)

Six of these more austere, less painterly works of equal size (30″x24″) were hung in a cluster in Merisier’s exhibit at Little Haiti Cultural Complex. But the show’s curator, Alfredo Rivera, does not refer to them at all in his essay on the artist’s paintings. Rather, as if taking his cues from Merisier’s honest but also misleading titles for some of his work, Rivera presents, for instance, “In Memory of Wifredo Lam,” a larger, direct 2009 takeoff on one of the breakthrough paintings, (specifically, the exhibited 2002 “Nègre feuille,” or nèg fèy (bush negro)), as being concerned with a would-be dynamic interplay between tradition and modernity, evident in Lam’s art. In fact, Merisier is hardly dealing with tradition or modernity in “In Memory.” The painting is much more about a constructed socio-cultural identity that Merisier compounds artistically: (Nèg fèy is an epithet leveled at a vast array of those perceived to be countryside inhabitants so as to further alienate them from would-be “more civilized” city dwellers.) Milking mercilessly this pet theme in “In Memory,” Merisier delineates a figure sprouting some leaves so as to equate “negro” and “bush” and, simultaneously, without succumbing to postmodern irony, performatively objectifies the stereotype. In other words, the wretched being the artist represents comes across as if it were stuck playing a role, which the picture’s shallow background and stage-like foreground reinforce. Thus, Merisier locks in place and even dehistoricizes his stereotyped persona by conflating its abjectness with an estranged and vacant existence that he seems to will and impose on it. It’s as if he had projected himself into the process of mirroring his own particular distillation of the idea of nèg fèy, ending up with an indirectly generated, sacralized self-portrait. (Once, when we were having dinner at a shabby steak joint on Manhattan’s 86th Street, out of the blue Merisier blurted out to me, “M pa nèg ki sosyab” – “I’m not a sociable person.”)

In trying unduly to universalize and aggrandize Merisier by linking him with other great European artists and by presenting him mostly as a modernist or “master” in the mold of Lam – without bothering to delve into the contradictory motivations, pretenses, and culturally specific circumstances that undergird Merisier’s practice – the Little Haiti show, through Rivera’s essay, saps the artist’s personhood and stymies both the actual and potential originality of his art. What’s being perpetuated here smacks of the critical sham the Foreign Haitian Art Establishment (as represented especially by Rodman) often engaged in when it sought to incestuously ballyhoo what it had already constructed and staged itself, namely, the lofty stature of the leading Primitifs. For instance, in Where Art Is Joy, his definitive book on Haitian art, Rodman makes a reasonably serious case for the long life and great works of Philomé Obin. But one might also cringe at his (condescending) ovation to the artist for relating that, supposedly, after a visit to the Louvre, Obin had seen nothing there that “impressed [him] as much as [his] own paintings.”

(Part 2)