A Difficult Childhood for a Late-Bloomer

The tendency to read Merisier’s work mostly as it relates to that of great European artists and to its connection solely to Haitian themes, without the filter of his individuality and the specific social and art- historical context from which it emanates, might have seriously hampered the development of his art career. But if it seems that he made some headway relatively late in his life, it’s in great part because he was a late bloomer, which is hard to understand when one sees the bracing and prepossessing aspects of what could be taken as mere post-impressionist takes on the folksy imagery in his paintings from the late seventies to early eighties.

I have not seen any of his work predating his arrival in the United States in 1968. But Edgar François, an apparently skilled draftsman from Haiti’s Centre d’Art, described Merisier’s images in the 1982 exhibition as “coarse” and not unlike his old drawings and watercolors “back in Haiti.” This, ironically, is a promising description for the works in question. Indeed, one could already detect in Merisier’s small, loosely painted “Nature morte” (1972) – illustrated in Michel Philippe Lerebours’ 2018 Bref regard sur deux siècles de peinture haitienne (1804-2004) – the symbolic dramas and tenebrous gleams that the artist favors in his more mature works.

Merisier was part of the small but expanding middle class in the aftermath of the U.S. Occupation of Haiti

But unlike peers such as Spencer Depas and Lucner Lazard, reportedly quick studies who started to make their names for their forays in mainstream modernist styles in the late forties and to whom Merisier was quite close, especially in New York (and sought behind their backs to rival), he did not start to hit his stride until about the mid- or late seventies. Much of the explanations for this late blooming and its relation to the thematic content of his work have to be deduced from the circumstances in which the artist found himself both before and after he began, at 27 years old, to draw and paint along with his buddy Raphael Denis at The Foyer Des Arts Plastiques back in 1956.

Born in Port-au-Prince on Jun. 2, 1929 to parents who had relinquished their Catholicism to join the Episcopal Church, Merisier was part of the small but expanding middle class in the aftermath of the U.S. Occupation of Haiti (1915-1934). This was a period of steadily resurging national confidence and pride. Merisier’s father, Joseph, had a cigar business that worked well enough for him to feed his seven children and to drive a car. But a fire would destroy his shop, halting the family’s socio-economic progress and triggering in him, as Merisier put it, a “tèt tounen” (“a mental malady”). Joseph would die in 1938, from which time his wife Rita, a seamstress, would be so hard put to make ends meet that supposedly she would allow her church’s orphanage and school simply to hold on to daughters Marie and Jacqueline for a few years.

Merisier would have his first communion at his family’s church, the Cathédrale Ste. Trinité, in downtown Port-au-Prince and would become a choirboy there. He’d befriend another choirboy, Charles George who, a few years later, evolved into an engaging, principled role model whom Merisier would continue to admire for the rest of his life. In about the mid-forties, both he and George, who was about two years older, would drop out of Ste. Trinité, owing in great part to the “gwo eskandal” (“great scandal”) there involving sexual exploitation of youths and priests-in-training by, Merisier related, the foreign-born head of Haiti’s Episcopal Church, Bishop Charles Alfred Voegeli, and other local church higher-ups.

Voegeli’s tenure as Bishop ran from 1943 to when he was expelled in 1964 by François Duvalier, who was seeking to “indigenize” Haiti’s clergy. It roughly corresponds to the period that ranged from the exhilarating “black power” presidency of Dumarsais Estimé (1946-1950) and the rollicking, tourist-filled years of “iron pants” Paul Magloire (1950-1956) to the bloody years of François Duvalier’s dictatorship, which compelled Merisier to flee to the Bahamas in 1965. He would take full advantage of this post-World War II era, when he and many among those who were more or less alienated from the culture of the gwo pèp (the masses) sought to open up themselves to the country’s folklore and, by extension, Vodou, the belief-system of the peasant majority.

Vodou and the Catholic Church

Vodou still had some powerful foes in the Catholic Church and the elite. Nevertheless, Merisier would attend many Vodou ceremonies in the popular neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince. But it was mostly for the fun of it, he claimed, for he, nor anybody else in his family (except for his mother Rita), was particularly religious. Looking back, he related that Ste. Trinité was basically a place to enjoy great meals and, when outings to other Episcopal parishes were organized, great picnics and camaraderie. Merisier’s disposition as an adult and, as mirrored in his art and utterances, supports this detached, nonreligious attitude. His paintings are often psychologically charged and darkly tumultuous and the figures in them, even when they are depictions of manbo and oungan (loosely, Vodou priestesses and priests) performing rites, come across as more stoic or trapped in their existence than as spiritual, mystical beings.

It was perhaps Merisier’s open, liberal attitude, (somewhat like that of Bishop Voegeli), in combination with the relative socio-economic clout that accrued to him once he had picked up masonry as a trade and then landed a temporary construction gig in Aquin, that led to the circumstances in which he would father, quite reluctantly, he said, his only child, his son Jean Alix. This occurred even though he was always “careful and disciplined with women” being that, he asserted, they are a “necessary evil.” But this one Elvire Bienaimé, the mistress of an older “gran nèg milat” (“big shot mulatto”), had “kept after” him in Aquin, Merisier said, in spite of him not wanting any “rapò” (sexual relations) with her. After about a two-month rapò, however, she later gave birth to his son with whom, since then, he would want virtually nothing to do. (Charles George, too, Merisier said, was the unwanted son of a “gran nèg” with a much less well-off woman.)

Voegeli, not unlike Merisier, was the default beneficiary of creations he had not necessarily asked for. As the bishop of a well-heeled church with American backing, he had the openness of mind to allow (with much input from Rodman, the Centre d’Art‘s apologist) the walls of Ste. Trinité to be covered in the early 1950s with colorful murals of Black figures in biblical scenes executed by only and mostly self-taught, working class artists. (A photograph published in Art in America in December 1951 showing Rodman standing in front of wonderful adjacent murals executed at the Centre in 1949 by Roland Dorcély, Max Pinchinat, and Lucner Lazard indicates that Rodman was quite aware of the artistic talents of these formally educated painters.) And it wasn’t just art that fell on Voegeli’s lap, as it were. (Some of his Haitian art collection reportedly would constitute a sizeable portion of that of the country’s first art museum, Le Musée d’Art Haitien du Collège Saint Pierre.) Whether it was his free-spirited attitude, the supposed social capital ensuing from his white skin, his U.S.-backed clout, or a combination of all three, that allowed him to be “quite open about his homosexuality” (to quote from the book Song of Haiti), the power differential between him and most of those he interfaced with during his tenure as bishop made it easy for him to “go to all the parties with an entourage of young priests, like a flock of black birds, young charming and socially popular.”

George, meanwhile, would emerge as a consciousness-raising egalitarian, academic mentor, and cultural progressive. With Merisier soaking in the atmosphere mostly from the sidelines, George would regularly hold court at the salon gatherings in his home near Mache Anba in downtown Port-au-Prince, without slacking on his pro-union activities and, unbeknownst to Merisier back then, clandestine political work, including sabotage. Merisier saw George as a sort of demigod, but someone to be emulated vicariously in artistic and intellectual circles. So George may well have been aware of his friend privileging sympathy over actual, on-the- ground engagement in the struggle of Haiti’s oppressed classes. This perhaps explains why Merisier would learn only later on of George dying along with the Communist novelist Jacques Stephen Alexis in an unsuccessful invasion to topple Duvalier in 1961. If Merisier was not necessarily committed directly to the struggle of the gwo pèp, as an unwavering but distant disciple of George, he would hold his ground faithfully on the metaphorical battlefields of his paintings for the rest of his life.

Class, Sex, and Tourism

Haitian folklore would be a central part of his focus, but traditional western art genres, including portraits, still-lifes, landscapes, as well as figurative representation of nudes would remain prominent throughout his career. Nevertheless, Merisier would steadfastly foreground in his work Haiti’s gwo pèp, depicted as engrossed and engulfed in their daily routines: peasants farming, making merry, or appealing to their Vodou lwa (spirits), etc.. Though in his work he often depicts manbo and oungan and Vodou paraphernalia, etc., spiritually, he was hardly committed, certainly no more so than his Sophistiqué foils, Spencer Depas (1925-1990), Lucner Lazard (1928-1998), and Raphael Denis (1934-2012). (In fact, Depas also saw himself as an oungan, and Merisier was wowed by his overall machismo and upward social mobility and, also by the supposed fact that he once administered a ritual bath to a New York Times reporter. And whereas in Merisier’s paintings the psychological and dramatic spectacle of Vodou subject matter generally supersedes spirituality, in both Lazard’s and Denis’ works, an abiding tinge of contemplative spirituality is evident.)

Often, Merisier presents his figures in unrelieved, abject conditions, living in disquieting worlds, trapped and, as he used to suggest, no better than wild beasts or mere objects. His identification with the downtrodden figures who often populate his paintings is so consistent and thorough that they compete with and, at times, seem to beggar the stark reality of life in Haiti.

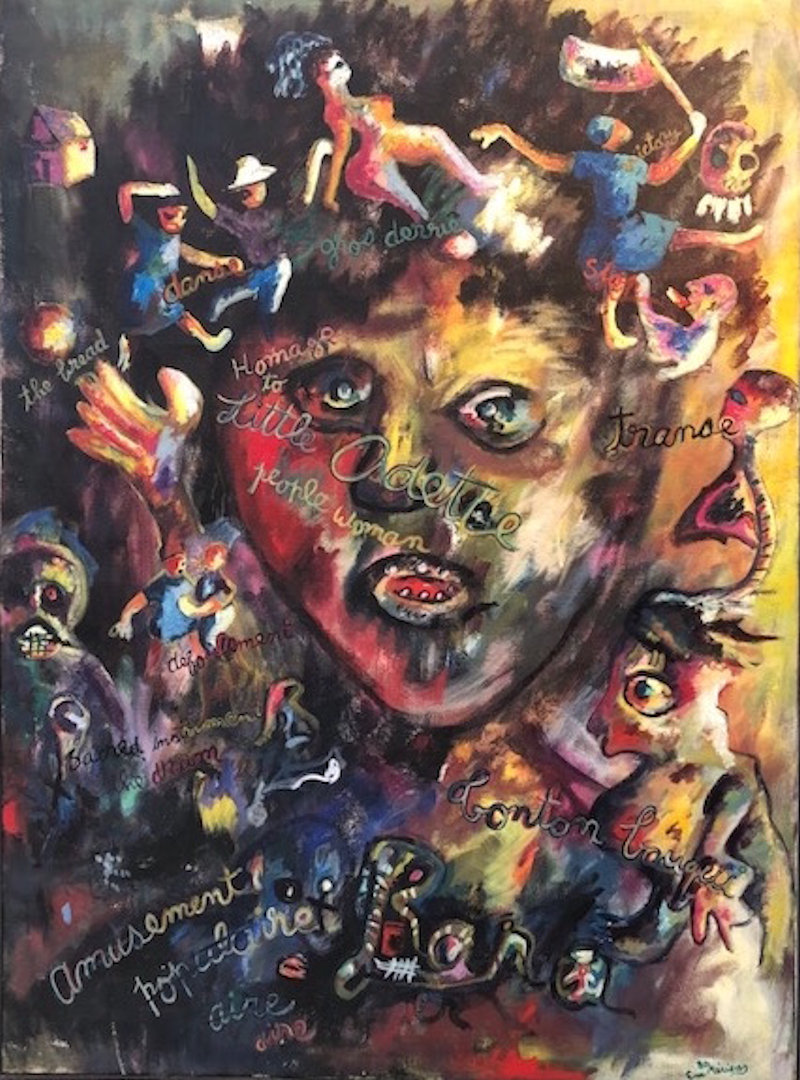

Yet, it’s worthwhile to probe a bit Merisier’s relationship with his concubine Odette Lamare during his post-Ste. Trinité period so as to illustrate his compartmentalized devotion to his gwo pèp. Indeed, years after living in New York, he would talk of her admiringly, as a noble femme du peuple (woman of the people), an icon of selflessness that ministered to his needs and basically kept him alive. To him, it was as if Odette had been his mother. To show his gratefulness and appreciation, he would send her money regularly and even memorialize her in one of his larger canvasses. Back then, in her crowded Portail Léogâne neighborhood, however, she lived a hardscrabble life as a lesivyè (laundress) in a single room dwelling, and he once beat on her for not following precisely his directives about some numbers she was supposed to bet on for him. (In New York, he kept stacks of legal pads with drawn-out number combinations carefully inscribed on every single line, and he would regularly spend an inordinate amount of money on lottery tickets.) For about 10 years Merisier relied on her for regular meals and for washing and ironing the white shirts that kept him “byen abiye” (“respectably dressed”), and though he hid at her place, sometimes for months. But when Duvalier’s goons were sniffing around for potential opponents, artists or just anyone rumored even to have met together, no one in his circles – not George, not his artists friends, not even his family, knew anything about her. It was not “this kind of relationship,” he related tersely, implying without any qualm that she was not the type one would present to polite society.

He was less forthcoming about his and George’s experience at Ste. Trinité. He let on that they never discussed what had – or had not – transpired sexually at the Church, and he never suggested that he or George was personally molested. But the psycho-sexual tension (or sublimation) in the themes or subject matter of his paintings, his repeated utterances against, not homosexuality, but sexual exploitation at the Church, his unabashed misogyny, his sometimes guarded private life back in Haiti and even in the New York area, etc. – all of this indicates that he was deeply marked by at least what he had witnessed or sensed, not just as an adolescent but afterwards in Port-au-Prince’s touristy, artsy scene of which the Centre d’Art was a focal point. Of course, aside from attracting tourists hankering for tropical thrills, back then Port-au-Prince drew to its shores a number of high-profile, free-spirited, or simply hard-driving celebrities looking to unwind, among them Hollywood figures such as Errol Flynn and “Gone with the Wind” producer David O. Selznick, and the writers John Goodwin and Truman Capote, whom Rodman once took to visit Hyppolite’s workplace. (Goodwin once threw a masked party, for which he asked an elite couple in Port-au-Prince to dress up as pimp and prostitute.) In short, in restricted more or less bourgeois circles, in which hedonistic tourists and the arts were part of the mix, there was reportedly an openness to sexual indulgences and preference that belied the staid, generally homophobic attitudes of the country’s small middle and upper classes.

the power differential between (white) foreigners and tourists and local Haitians at least in part facilitated sexual adventures.

For instance, the gay Dominican painter Xavier Amiama lived openly with his partner and, the artist Georges Remponeau recalled, the mostly upper crust artists of the Centre regularly attended parties at the couple’s home. Merisier himself related that back in Haiti he had a great friendship with a certain Salem (Dominican-born and raised but of Egyptian parentage), who was “très connu” (“well known”) as a gay person in Port-au-Prince. Among the scattered details Merisier proffered about Salem are that he used to go out at night, and that back in the Dominican Republic, he had sown clothes for the wife of the dictator Rafael Trujillo. Although he was not well-known as an artist in Haiti, his talents were such that, at times, he guided Amiama in his works. Perhaps that’s partly why Merisier, who said he had a tough time selling his own watercolors back then, once facilitated Salem selling four paintings to the musician and art dealer-collector Issa Saieh. Years later, Salem would end up in Philadelphia and, down on his luck with no home and no papers, he would visit Merisier in New York when he was married to Lucy French. He would feed his friend all weekend long, he said. It was during one such visit that Merisier took him to see Lazard and his wife, who supposedly were “very uncomfortable” with Salem’s presence.

But it was also apparently the power differential between (white) foreigners and tourists and local Haitians that at least in part facilitated sexual adventures. Tellingly, DeWitt Peters allegedly had a liaison with Merisier’s older brother Mortes, an aspiring self-taught artist whose still-life of fruits is in the collection at Ramapo College’s Selden Rodman Gallery. Peters founded the Centre d’Art in 1944 and ran it with the support of a few educated local artists, such as Remponeau and, then, Pierre Monosiet who, aside from being Peters’ alleged lover, would become from 1953 to 1963 the Centre‘s assistant director. (Still functioning, with much foreign support, compared with the Foyer which petered out in 1956 soon after Merisier had joined it, the Centre had the crucial backing of Rodman and, especially, the local Institut Haitiano-Americain. This entity was a vintage neocolonial outfit of the U.S. State Department that once actually threatened to withhold funding from the Centre if the original name, “Centre d’Art de l’Institut Haitiano-Americain,” was changed to “Le Centre d’Art.” And Rodman himself, a Yale graduate, poet, and writer who at first had a certain profile in leftist intellectual and literary circles in the United States, had worked for the CIA’s precursor, the OSS. during World War II.) Whether or not Merisier knew then or later in New York anything about Peter’s sexual escapades at the Centre and beyond, or about his encounters with Mortes in particular, he did not vouchsafe a word about it, except to suggest that his brother was unbearably cantankerous and inapproachable. Merisier, for much of his life, would remain mostly estranged from him and his family.

(To be continued)