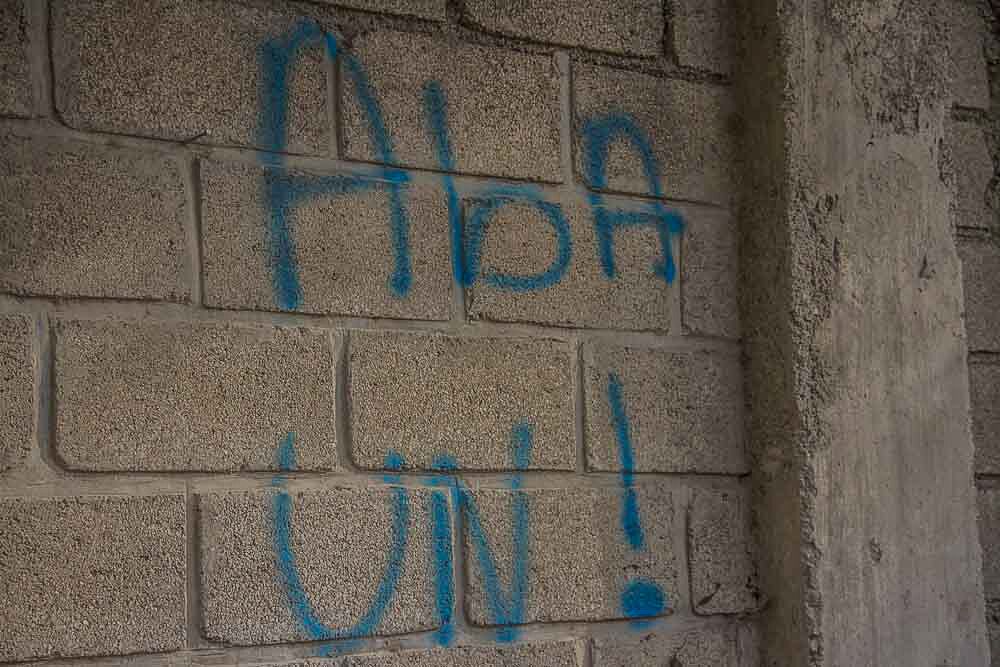

MINUSTAH is gone, replaced by MINUJUSTH. UN “peace-keepers” have a very controversial record in Haiti, having left many families devastated. Over 13 years, some “peacekeepers” have raped and taken advantage of people in precarious situations, sometimes even children. For the victims, they can only resort to lawsuits or personal appeals; Haitian authorities have undertaken no prosecutions. For the victims, there remains only a devastated life and the unanswered questions of children born from forced or forbidden relations with MINUSTAH troops.

“It destroyed me,” said Angela Jean Philippe, 30. “I even wrote a suicide letter to my parents. But, I changed my mind after the advice of a friend who took me in after I was forced to leave my family’s home due to the pressure of my sister, who insulted me day and night . I love children, but I did not want to have one in this [painful] situation.”

Credit: Milo Milfort

In tears, she explains that she was raped by a Nigerian soldier of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) one day when she went to a mission base at the request of a friend. “He did not use his firearm,” said Angela. “He forced me. I did not want it. I [hid] it from my family because they did not know I was going out [that night]. For them, I was in church.”

Her daughter comes to her during her interview for this article. Immediately, Angela asks her to leave for fear that she will hear the sad story that has upended her life.

“I cried almost every day,” she says. “I had to tell my family after they discovered my pregnancy. They were not happy because I had hidden it from them. I began to resign myself to my fate when the child was two years old.”

This aggression dates back to 2009. She was 22 years old and believes that she was immature. Years later, it was an empty and exhausted Angela whom we met in a poor neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, surrounded by her relatives, who continue to support her.

Credit: Milo Milfort

Although shame consumed her from the start, she did not sit idly by. She had to do the best she could for her child, born on Nov. 9, 2009. She complained to the Mission Conduct and Discipline section at the UN Log Base. “I did not file a complaint for rape, but for paternity and child support,” she said. “Rape is a crime, but I do not want everyone to know about it, and I do not want my daughter to learn about it.”

What she will tell her daughter in the future already haunts her. And the rare conversations they have had on the subject reopen a wound that is still raw. “Once I tried talking to my daughter. She was sad. I asked her, if she loved me. She replied: Yes. I told her: If you really love me, do not ask me about your father anymore. She said to me: Why? I replied: Your father is married, he has other children. He does not love you. Otherwise he would not abandon you. Since then, she has not spoken to me about her father anymore.”

The young mother cares more about the present moment. “She is small and smart. She was watching something on TV. Later, she asked me: ‘Mommy, what is rape?’” Angela relates, before sinking into silence.

Angela Jean Philippe (not her real name) is not the only Haitian woman who is victim of sexual abuse and exploitation. Her child, Belinda Jean Philippe (not her real name), 8, is not the only “MINUSTAH baby” left by the UN mission in Haiti. There are several dozen victims: men, women, and children.

The MINUSTAH soldiers are no longer there. They officially packed up on Oct. 15, 2017, after 13 years of a controversial mission. They leave behind victims of abuse and exploitation, children who will never know their fathers, and whole families branded with shame.

The total number of official allegations of SEA (Sexual Exploitation and Abuse – as the UN calls it) involving MINUSTAH, for the period 2007-2017, is 114, according to UN statistics. This is out of a global total of over 870 for “peacekeeping” missions worldwide.

UN soldiers accused are from Bangladesh, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Canada, Guatemala, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and Rwanda. Of the allegations, 35 are confirmed, out of a global total estimated at 143 between 2010 and 2017.

Some national governments have taken measures: there are 12 “imprisoned” persons, 8 of them on charges of sexual exploitation; 10 cases are pending; there have been five dismissals and one suspension. The UN says it has “repatriated” 31 guilty soldiers.

So out of 114 allegations concerning the UN mission in Haiti, only 82 investigations have been conducted out of a global total of 556. This means that 32 cases have not even been taken into account. Moreover, the UN statistics are not exhaustive. They tend to minimize the problem’s gravity. So the numbers should be taken with a grain of salt.

For example, many figures that the international press echoed at specific times seem to be forgotten by the United Nations. In 2007, more than 100 Sri Lankan soldiers from MINUSTAH were repatriated on suspicion of sexual abuse and exploitation – some of them on boys and girls between 2004 and 2007.

The UN announced an investigation, but so far, its results are not yet published.

MINUSTAH’s litany of sexual abuse and exploitation is long. In 2015, UN “peacekeepers” in Haiti were implicated in sexual exploitation cases, according to a report by the UN Office of Internal Oversight Services. Among other things, this document highlights the fact that 230 Haitian women (1/3 of whom are minors) say they have had dealings with “peacekeepers.” About seven women were reportedly aware of the UN policy prohibiting sexual relations with UN “peacekeepers,” but none were aware of a hotline for reporting abuse.

In addition, the mission states that there is no reliable data available for years prior to 2007, in an exclusive interview with ENQUET’ACTION. Yet 2004-2006 is a turning point in the denunciation of sexual abuse and exploitation committed by UN “peacekeepers.”

Did Peacekeepers Clean Up Some Areas?

The overwhelming majority of intimate/sexual relations between Haitians and UN soldiers are in exchange for food (cookies, juice, etc.), money, clothing, perfumes, cell phones, computers, care items for babies, etc. Poverty and vulnerability are indescribable in a country where nearly 60% of the population lives below the poverty line on $2.41US per day. Precarious employment contributes to feminizing poverty with only 30% of women in formal jobs and 71% of women without land or a home.

Easy prey because of their precarious situation, the victims of the “peacekeepers” were caught in a vicious circle. “The mothers of MINUSTAH babies in search of well-being, acquire many other children,” reports Angela Jean Philippe, who has met several other victims.

“The victims are numerous,” she said. “I cannot give [exact] numbers. Some are afraid. They are numerous in the provinces and come from everywhere to [make complaints] to the MINUSTAH’s office of discipline and conduct.”

The situation is much more worrying than we thought. The number of unreported cases seems to far exceed that of reported cases in UN official statistics. “The UN mission soldiers committed damage [sexual abuse and exploitation] in all the areas where they were,” she said. “They depart and leave us with many children.”

For example, the town of Léogane, located 32 km west of Port-au-Prince, has many victims, according to testimony collected on site. Some victims have children over 10 years old. “She always needs her father,” says shopkeeper Marie Ange Haitis, 40, a woman filled with affection which she lavishes on her child, Samantha Haitis, 9. “She would like to know him, nurtures the desire to see him and says she would like to have a dad like other children.” Intelligent and cheerful, the girl is distinctly different from the other two children in the family by her Métis traits.

Samantha is the result of 6-7 months of intimate relations between her mother and a Sri Lankan battalion soldier based in Braches in Léogâne – before he packed up in June 2007. “It was not rape, but it was not totally agreed,” she says, adding: “It’s not my fault that this happened. It is life that is the cause. I can do nothing. I always tell her that she is the daughter of a visiting soldier. She asks me why I made that choice. Because all children have a father, but she does not,” Haïtis said.

According to the UN and Sri Lankan officials, Samantha’s father accepted the paternity of the child without any DNA test and was “fired”. A one-time payment was made for the girl in 2016. This type of situation is rare. Haitis actually lodged a complaint against the soldier in the UN’s discipline and conduct section. “I was asked to keep the secret, to stop any prosecution against the guilty UN soldier and to tell Samantha that she has no father,” she said regretfully.

From 2007 to 2017, no less than 876 allegations were reported around the world concerning UN missions. At least 1/3 involve sexual exploitation. Nearly 1000 communications and requests for action were sent by the United Nations to Member States, for a total of at least 620 communications received. The phenomenon is global. However, romantic, sexual, or intimate relationships are forbidden by the United Nations. The vast majority of women and men in Haiti are unaware of it, but MINUSTAH soldiers and other so-called “peacekeepers” know it.

A Huge Denial of Human Rights!

A March 2016 document on sexual abuse and exploitation of women, girls, and young men by United Nations soldiers, and violations of the right to redress was submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Council by more than a dozen national and international organizations for the defense and promotion of human rights – including the Office of International Lawyers (BAI), Fanm Viktim Leve Kanpe (FAVILEK), and the Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti ( IJDH) – denouncing the UN mission and accusing it of violating the rights of Haitians.

Despite several protections in Haitian law and international laws on the rights of victims of sexual exploitation and violence, and mothers of abandoned children, they do not have access to remedies, they complain, while lambasting the Haitian state for not respecting its obligations to protect women against all forms of violence and exploitation based on gender. “The victims feel defeated knowing that they cannot reach the men who raped them when they leave Haiti; they will not have the right to see them in front of a judge,” complained these organizations. In most cases, children are stigmatized, and because of a lack of financial support from fathers, they do not go to school and are not well-fed. All this happens because the State does not make efforts to fight against impunity and parental irresponsibility, these organizations reported. “The immunity of United Nations personnel presents an absolutely critical barrier to accountability for the SEA and obtaining reparations for the victims, which makes a culture of impunity prevail,” they said.

Credit: Milo Milfort

Thus, victims, women and men, prefer to suffer in silence or hesitate to report abuse to the very institution that houses the perpetrators. Among other reasons, they cite: fear of reprisals, stigmatization by Haitian staff, the rejection of their complaints by security personnel, but also the lack of concrete follow-up for complaints already filed. “The wounds are far from healed,” complains Angela. “I feel bad every time I talk about it.” Despite the promises of her child’s father (who came to see her in June 2009 promising to assume his paternal responsibilities, yet he left a month later), complaints filed, investigations conducted by the UN in her neighborhood, she received nothing. Worse, so far, “I’ve never been called for DNA testing. I take care of my child alone. I consider that he [the father] is dead! ”

According to much information gathered in the field, the UN mission allegedly bribed female victims by offering them jobs to discourage them in their quest for justice and reparations. Some have even been humiliated by agents in the UN system.

In August 2016, mothers of children abandoned by MINUSTAH “peacekeepers” issued summonses seeking paternity, recovery of maintenance claims, and custody of their children to no less than nine soldiers, some of whom are from Uruguay, Argentina, and Sri Lanka. This, with the help of the Office of International Lawyers (BAI) and the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti (IJDH). These nine Haitian mothers allege they become pregnant and were then abandoned with the responsibility for their children. The applicants ask these blue helmets to assume their responsibilities as fathers towards their children.

More than a Year Later, No Answer

Ditto for the call for cooperation launched to Sandra Honoré, MINUSTAH’s head, and Pierrot Delienne, then Haitian Foreign Affairs Minister. Even less for the request that was sent to them to provide all the information that can identify the defendants and especially to deliver, as soon as possible, the results of DNA tests conducted in February 2014 on their children.

Faced with this total disregard, the victims will not sit idly by. “We will move for a summary judgement against them,” such is the next step in this battle, declared the BAI’s Mario Joseph, the applicants’ lawyer. “We do not know what will happen, but we are determined to go all the way,” said Mr. Joseph, who also defends cholera victims in Haiti. “It is terrible to see how the UN violates the rights of the people it should protect. Worse, even UNICEF says nothing. It’s as if the MINUSTAH babies are not children.”

The Haitian State in Silent Mode!

The Haitian state, or at least the various governments that have succeeded each other from 2004 to 2017, have never officially made any pronouncement or taken a position on the allegations of sexual abuse and exploitation by “peacekeepers.” Victims, like those of cholera, are left alone in their fight for recognition of paternity and alimony claims.

Credit: Milo Milfort

The Haitian state’s complicit silence in 2011, during the highly-publicized scandal of a Haitian teenager’s rape by at least five Uruguayan soldiers, is troubling and confusing. The act was filmed by the attackers and went viral on the Internet. The perpetrators have not been tried in Haiti. Four of them were convicted in Uruguay of private violence, a smaller charge.

It is only recently, on Oct. 16, 2017, that Antonio Rodrigue, Haiti’s Foreign Minister, during the official opening ceremony of the United Nations Mission for the Support of Justice in Haiti (MINUJUSTH), gave a confused statement on the subject. “It is also time to draw the necessary lessons from some not very laudable experiences of the last 13 years,” he said. “I want to refer in particular to cases of sexual abuse.” He added: “Strict commitment to regulations must be put in place to promote the implementation of the ‘zero tolerance’ [of sexual abuse] policy advocated by the UN Secretary-General.”

The Haitian State “validated this situation of impunity in practice, by not launching criminal proceedings against MINUSTAH personnel, not informing the victims of their rights or supporting them in the filing of civil complaints, and finally, by not demanding that the mission honor its obligation to transfer the prosecutions to local courts,” said national and international human rights organizations, including BAI and IJDH.

While human rights organizations criticize the Haitian authorities for their inaction, the UN sees the matter very differently. “Given that the aforementioned allegations involve international staff, the Haitian authorities should normally not be involved in the investigation,” MINUSTAH said, adding that for 13 years it has worked alongside and in support of national and local authorities in Haiti. “It is a partner in the [UN] organization’s efforts to combat sexual exploitation and abuse,” it said.

Reality proves the opposite.

The UN Missions Follow Each Other and Are Similar?

In addition to the crimes and sexual abuse against minors, men, and women, MINUSTAH is accused of introducing cholera into Haiti, which has killed as many as 10,000 people and sickened close to one million. Many international studies have confirmed this. This prompted the UN to partially admit its responsibilities in December 2016. Nevertheless, the plan to fight the disease is under-funded by the UN, and the victims continue to demand justice and reparations.

The MINUSTAH was established in June 2004 by UN Security Council Resolution 1542, succeeding an Interim Multinational Force (USA, Canada and France) that the UN had authorized in February 2004 after President Jean Bertrand Aristide’s forced departure into exile. MINUSTAH’s mission was “to restore a secure and stable atmosphere, to support the ongoing political process, to strengthen governmental institutions and the structures of the rule of law, and to promote and protect human rights.”

From 1990 to date, Haiti has received no less than nine missions of “support, maintenance, peace support or stabilization”:

1) United Nations Observer Group for the Verification of Elections in Haiti (ONUVEH) in 1990;

2) The International Civilian Mission in Haiti (MICIVIH) / 1993 – 1994

3) The United Nations Mission in Haiti (MINUHA) / 1993 – 1996

4) United Nations Support Mission in Haiti (MANUH) / 1996 – 1997

5) United Nations Transition Mission in Haiti (MITNUH) / 1997

6) The United Nations Civilian Police Mission in Haiti (MIPONUH) / 1997-2000

7) The International Civilian Support Mission in Haiti (MICAH) / 2000-2004

8) United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), which lasted 13 years (June 2004 – October 2017)

9) The latter will be followed by a new mission named the United Nations Mission for the Support of Justice in Haiti (MINUJUSTH) / October 2017 – April 2018)

MINUSTAH, What Is the Balance Sheet after 13 Years?

Faced with this succession of missions, the Haitian sociologist and professor at the State University of Haiti (UEH) Franck Séguy, who has done a lot of research on the issue, notes that contrary to the perception that saw in MINUSTAH a mission of peace, humanitarian aid, and development promotion, it was rather a “generator of sadness.” For him, “in these three areas [public security, political governance, and human rights], the failure of MINUSTAH is obvious to Haitians.”

Séguy says that this mission was useless in Haiti, as will perhaps be its successor. Transactional rape and sex, especially on minors, is another major blotch on the UN’s reputation. “As a real occupying force, the MINUSTAH uses rape as a weapon of war,” he writes in his text “Ocupación, cólera y negocios: las virtuosas actuaciones de la MINUSTAH “, in the book” Farsa neodesarrollista y las alternativas populares en America Latina y el Caribe “. “It humiliates, exploits, and dominates the most vulnerable people who come into contact with it to guarantee its survival, or simply because they are poor.”

“It is difficult to deny or conceal that MINUSTAH’s support has contributed more to weakening state institutions than to promoting democracy, the rule of law, and institutional development,” he concludes.

The UN Recognizes, but Does it Take Responsibility?

“The MINUSTAH is aware” that “acts of sexual exploitation and abuse are serious violations of human rights. They are contrary to the values and efforts of the organization in support of the authorities and the Haitian people,” a MINUSTAH official responded in an interview via e-mail. The organization is categorically opposed to abuse and exploitation, but also implicitly admits that some of its soldiers have violated people’s rights.

To address the problem, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has appointed Jane Connors as a victim advocate for the entire system on Aug. 25, 2017, to “ensure that the United Nations system provides tangible and sustainable assistance to victims of sexual exploitation and abuse.” She must also work with the other mission agencies on the implementation of the three-pronged eradication strategy (prevention, treatment, and support for victims).

According to the UN, Connors should work with government institutions, civil society, national and legal organizations, and human rights organizations to build support networks and ensure that local laws, including remedies for victims, be fully taken into account. Connors’ appointment did not get much attention in Haiti. We do not even talk about it. “Sexual exploitation and sexual abuse are in no way tolerated within MINUSTAH. There is no complacency or impunity,” said the mission in an interview made before its departure.

The problem with the continuity of MINUJUSTH’s working on processing allegations of sexual abuse and exploitation against MINUSTAH personnel is that the United Nations will continue to investigate themselves.

If this strategy helps to reduce the problem, it does not help solve it. MINUSTAH says it will “ensure that all allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse are immediately and fully addressed. The United Nations systematically follows each case to ensure justice and accountability.” However, further on, it recognizes that investigations into allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse are sometimes lengthy, in particular those conducted by Member States. “Remember, the investigation must be thorough and respect due process. It takes time, just like police investigations. The main point is that each claim is treated,” the spokesperson concedes. “The mission informs the victims of the outcome of the investigation. Victims should not be discouraged. The organization places the rights and dignity of victims at the center of our attention from the moment a complaint is received until there is a result.”

Should We Expect Better from MINUJUSTH?

MINUSTAH left Haiti on Oct. 15 but has been replaced by a smaller entity, which is the United Nations Mission for the Support of Justice in Haiti (MINUJUSTH). It has up to seven police units (980 people) and 295 non-incorporated police officers and is expected to last for at least six months until Apr. 15, 2018. The UN Security Council’s 15 members unanimously adopted Resolution 2350, presented by the United States.

MINUJUSTH is charged with “helping the Haitian government to strengthen the institutions of the rule of law in Haiti, to support and further develop the Haitian National Police, and to monitor the human rights situation in Haiti, [and] to report and analyze it.” The council also authorizes MINUJUSTH to “protect civilians threatened with imminent physical violence within its means and areas of deployment.”

The UN continues to make promises. “There will be continuity of case tracking. MINUJUSTH will continue to facilitate applications for paternity against former MINUSTAH staff in collaboration with UN headquarters and member states. There will be no stopping the efforts of an appropriate response to cases of sexual exploitation and abuse. A team of conduct and discipline receives and “treats” allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse against MINUSTAH personnel. It is supposed to monitor the continued assistance to victims.

Jocelyne Colas Noël, director of the Justice and Peace Commission of the Episcopal Conference believes that responsibilities must be taken. “These are not children without dads, but children who have a dad who refuses to assume his responsibilities or because he is not required to assume it. Soldiers on mission who depart and leave children behind constitutes a violation of these children’s rights to live well and in the company of their father and mother. These children are deprived of the opportunity to have a father who takes care of them,” she says. For her, this situation will have catastrophic impacts on children who are raised in a single-parent family away from their father’s attention. “They are children growing up unbalanced,” she warns.

ONUVEH, MICIVIH, MINUHA, MANUH, MITNUH, MIPONUH, MICAH, MINUSTAH, MINUJUSTH. The missions follow each other, will the damage be similar? Human rights activist Jocelyne Colas Noel points at the occupation and domination that hide behind the presence of international forces on Haitian territory. “I doubted very much that the Haitian state would defend the victims. This situation is part of the damage that the MINUSTAH leaves us. MINUJUSTH/MINUSTAH, unfortunately it’s the same family. MINUJUSTH arrives under the same conditions as MINUSTAH. The state never takes into consideration protests against their presence in the country. Instead of settling the question, it prefers to enter into their pattern of occupation. The occupant is only changing its name. It has lots of new names. It changes color every minute!”

The problem with the continuity of MINUJUSTH’s working on processing allegations of sexual abuse and exploitation against MINUSTAH personnel is that the United Nations will continue to investigate themselves. At no time was the possibility proposed of setting up an entity, appointing an expert or an independent commission to take over the investigation of the human rights abuses committed by UN personnel in Haiti.

This could to some extent reassure victims that the UN wants to change things in terms of transparency, as it does by appointing an independent expert on the human rights situation.

Until then, MINUJUSTH’s partiality and credibility is completely in question.

* ENQUET’ACTION is an online source of multimedia, deep-digging, investigative journalism, created in February 2017 in Port-au-Prince and officially launched in June 2017. Focused on quality journalism that believes in free access to information, it aims to become an indispensable source of information for national and international media, as well as for the public. It was born from the desire to reconnect with journalism’s fundamental mission of seeking the truth to allow the press to truly play its role of a counter-power.

(Translated from French by Kim Ives of Haïti Liberté)