On Mar. 1, 2016, the U.S. Appeals Court in New York heard oral arguments on whether the United Nations has immunity from a class action lawsuit charging its soldiers negligently dumped their sewage into Haiti’s largest river, thereby unleashing the world’s worst cholera epidemic.

In October 2010, an outpost of Nepalese blue-helmets, several scientific studies have found, allowed feces from their outhouses to flow into the headwaters of the Artibonite River, which is used for drinking, washing, and irrigation of Haiti’s rice fields. As a result, over the past five and half years, close to 10,000 Haitians have died from the fecally-transmitted cholera bacteria, and close to 900,000 have been sickened.

On Jan. 9, 2015, Judge J. Paul Oetken dismissed the claims made by lawyers from the Boston-based Institute for Democracy and Justice in Haiti (IJDH) and the Port-au-Prince-based Office of International Lawyers (BAI) on behalf of Haitian cholera victims and their families in the case known as Georges vs. United Nations. Despite vigorous arguments from the IJDH that its clients and Haitians in general had no other recourse to justice and compensation for the injuries they’ve endured, Judge Oetken found that “the United Nations, [the UN military occupation force] MINUSTAH, [UN Secretary General] Ban Ki-moon, and [then MINUSTAH chief] Edmond Mulet are absolutely immune from suit in this Court.”

But a three-judge panel for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second District has questions about that ruling and agreed to hear oral arguments from both the IJDH’s Beatrice Lindstrom, spearheading the appeal, and Assistant U.S. Attorney Ellen Blain, who had argued on behalf of the UN in the original Oct. 23, 2014 hearing before Oetken. The UN did not send any other lawyers to defend itself in either the 2015 or 2016 hearings. (“They are taking this absolute radical position that they are not subject to any law so they don’t even show up to court,” said IJDH’s executive director Brian Concannon, Jr.

Judges Gerard E. Lynch, Barrington Daniels Parker, Jr., and José A. Cabranes peppered Lindstrom and Blain with questions as they presented their arguments: Has the UN given any remedy? Assuming there is a condition precedent to immunity, who has the rights of enforcement? If this was a claim against the military, instead of Nepalese peacekeepers, would there be immunity? Since the UN is not present, never entered an appearance, and the U.S. Government is not a party, what would be the procedure if the plaintiff prevails? Is there any precedent in any jurisdiction, international cases too, for a tort claim against the actual UN – not UNESCO – the UN itself? Is this unprecedented?

the UN’s own experts issued a stinging condemnation of the UN’s conduct so far.

The hearing comes as public support for the plaintiffs continues to grow. In an October 2015 letter, made public last week, the UN’s own experts issued a stinging condemnation of the UN’s conduct so far. Four UN Special Rapporteurs and a UN Independent Expert wrote that the UN’s stonewalling of the cholera case has resulted in “the inability of the victims of the cholera outbreak to vindicate their rights and to obtain access to a remedy for the harms suffered to which human rights law entitles them.” The UN experts warned that the UN’s attempt to hide behind immunity “undermines the reputation of the United Nations, calls into question the ethical framework within which its peace-keeping forces operate, and challenges the credibility of the Organization as an entity that respects human rights.” They concluded that it is “essential that the victims of cholera have access to a transparent, independent and impartial mechanism that can review their claims… in order to ensure adequate reparation, including restitution, compensation, satisfaction and guarantees of non-repetition.”

In support of the appeal, 86 scholars, Haitian-American leaders, human rights experts, and former UN officials submitted six legal briefs in June 2015. In July 2015, 154 Haitian-American leaders and organizations sent a letter to U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Ban Ki-moon demanding UN accountability.

On Dec. 10, 2015 – Human Rights Day – over 2,000 letters from cholera victims and their families were delivered to the United Nations headquarters in. “ If the peacekeepers from MINUSTAH did not contaminate our water supply with fecal matter, I never would have been infected with this disease,” wrote Gérard St. Fleur in Kreyòl from Pierre Rouge, for example. “The MINUSTAH peacekeepers do not respect us and treat us worse than animals. For at least these reasons, I am asking for justice and reparation.”

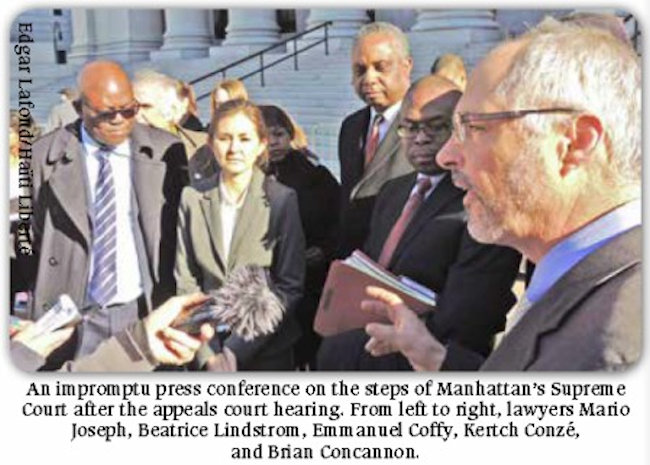

About 50 people – the press, law students, lawyers for parallel suits and amici briefs – packed the courtroom and the same-capacity overflow room outside. Haitian-American lawyers and cholera justice advocates Emmanuel Coffy from New Jersey and Kertch Conzé from Florida also attended the hearing.

The crux of this case is whether the UN can invoke the Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations (CPIUN) while refusing to provide a claims commission or other mechanism to address the cholera victims claims. The IJDH began this legal journey with a petition within the UN grievance system in November 2011. The UN answered 15 months later with a two-page letter saying any claims were “not receivable.”

“The question is about access to justice,” said Lindstrom during a court-step press conference after the hearing. “It is clear we are on the right side of history here. It’s just a question of the UN coming around and upholding its obligations that have been in effect since 1946.”

“I think that the United Nations is getting to the end of this absolute immunity,” said the BAI’s lead lawyer Mario Joseph. “We also think this hearing sends a message to the Haitian government, which, up until now, has not helped Haiti’s poorest people with their demands. The judges kept coming back to the question: where is the Haitian government? What is it doing?”

Should the judges find for the plaintiffs, Concannon says the case will likely be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court by the government. Asked about this eventuality by the judges at the Mar. 1 hearing, Blain said she didn’t know how things would proceed because the is just an amicus (i.e. legal “friend”) of the UN. The IJDH intends to appeal to the Supreme Court should they lose. Concannon foresees the appeals process taking months and the Supreme Court process potentially years.

“This case raises a fairly serious question about the U.S. relationship to the UN, and the UN’s relationship with the vulnerable population in countries where it has peace-keeping missions,” he said.

Overall, Concannon said he was “heartened… to see the judges asking very good questions both about the consequences of the UN’s ignoring its legal obligations but also bringing it back to the impact on the victims. We think this sent a message.”

Lindstrom echoed those sentiments. “I think the court certainly recognizes that there are extremely troubling consequences that flow from a recognition of immunity in this case, that are different from other cases where UN immunity has been accorded,” she said. “This is fundamentally a question about victims who have suffered real harm and have been denied any kind of due process whatsoever. That was the message that I think resounded extensively in the court today.”