Prominent political activist, protest singer, and vodou priestess Annette “Sò An” Auguste, 73, died on Apr. 17, 2020 at the Bernard Mevs Hospital in Port-au-Prince, Haiti after a five year struggle with breast cancer.

“She had already died politically,” said Tony Jean-Thénor, a leader of the Veye Yo popular organization in Miami, referring to Sò An’s defection to the ranks of President Michel Martelly’s neo-Duvalierist Haitian Bald-Headed Party (PHTK) in 2015, when she unsuccessfully ran for Senator of the West Department under the party’s banner. “She was still physically living, but she no longer embodied the militancy she had once symbolized.”

For decades, Sò An (Sister Anne) had been an outspoken activist and leader in the democratic struggle against the Duvalier dictatorship and then in the progressive popular organizations and parties that sprang up after its 1986 fall.

She rose to become a leading member of the Lavalas Family Political Organization (FL), spending two years and three months in Pétionville’s filthy, crowded, rodent-infested jail as a political prisoner during the 2004-2006 coup d’état against former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

But she grew estranged from the FL after failing in a bid to reform its democratic mechanisms in the years between her release from jail and the 2010-2011 elections.

Born in Port-au-Prince on Aug. 30, 1946, Annette Auguste was the fourth of eight children (three girls, five boys) of André and Yvonne Auguste. Her father and most of her brothers were professional and semi-professional soccer players, with her younger brother Arsène Auguste being a member of Haiti’s 1974 National Team, which played valiantly in that year’s World Cup.

She lived in Haiti until 1977, when she immigrated to the U.S.. There, she set up a record and bric-a-brac store named “Poto Mitan” (meaning the center pole of a vodou temple) on Church Avenue and E. 47th Street in the middle of Brooklyn’s Little Haiti.

Having two of her five sons with Henri Robert (Bob) Ménélas, a musician with the popular Haitian konpa group Les Ambassadeurs, she also began to sing and record music herself.

Having been involved in vodou since she was a teenager, Sò An became a mambo (a vodou priestess), holding ceremonies at the peristil (vodou temple) in her Linden Avenue three-bedroom apartment.

Above all, she became deeply involved in Haitian political activities, taking part as an organizer, speaker, performer, and permit holder at demonstrations ranging from the community’s fight against being stigmatized as AIDS carriers in the early 1980s to the mobilizations against the Duvalier dictatorship and the first coup d’état against Aristide in 1991.

After that coup, she returned to Haiti in 1994, where she and singer Manno Charlemagne, her close friend who had sometimes stayed at her 899 East 37th Street home in Brooklyn, formed a popular organization (which later became a party) named Pouvwa Rasanbleman Òganizasyon Popilè (The Power of Popular Organizations Assembled ) or PROP.

In Haiti, as in New York, she had tremendous capacity and prestige as a street organizer, gradually becoming a Lavalas Family leader and abandoning PROP.

At the same time, she expanded her musical career, forming a all-women chorale group, Koral la, which gave rousing concerts at events like the 2003 Congress of the National Popular Party (PPN).

After the second coup against Aristide and the ensuing foreign military occupation, U.S. Marines arrested Auguste on May 10, 2004 after storming her Delmas 16 home in the middle of the night, blasting open her door with explosives, shooting dead her two dogs, handcuffing her 5-year-old grandson, and traumatizing her large family, including several other small children.

“It was only American soldiers who invaded my home, without an arrest warrant, and forcibly took me away in chains while the Haitian police sat passively in their cars outside,” she wrote in a statement from her cell after the arrest. “The [George W.] Bush government’s Marines said that they undertook this violent action against me and my family because I was planning to attack their forces and undermine security and stability in my homeland… How can they be so cynical when they know quite well it was they, along with the French government, who undermined Haiti’s stability by forcibly removing our constitutional president on Feb. 29, 2004?”

In the weeks following her arrest, pro-coup pundits, abetted by hack foreign journalists, peddled various versions of an outlandish rumor that Sò An had sacrificed a baby at a 2000 vodou ceremony to ensure Aristide’s five year presidency. “It’s sad and ridiculous the outright lies some people will stoop to,” Sò An told this journalist, who interviewed her in her jail cell in 2005.

As international outcry against her arrest grew, de facto Prime Minister Gérard Latortue’s government changed the charges against her to organizing an attack by counter-demonstrators against university students protesting Aristide’s government on Dec. 5, 2003.

But a judge dismissed the charges as groundless, and Sò An was finally released from prison on Aug. 14, 2006. With Aristide still exiled in South Africa, she became one of the FL’s leading representatives, sitting on the Executive Committee with Lionel Etienne, Jacques Mathelier, and Dr. Maryse Narcisse.

In late 2006, she toured various popular resistance bases in Belair and Cité Soleil, which were engaged in armed resistance against the occupation troops of the UN Mission to Stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH).

She also traveled back to New York, where she held mass meetings, encouraging the Haitian community to continue its pressure for Aristide’s return and for UN troops to leave. She also appeared at a few demonstrations, like one in May 2008 in Brooklyn demanding the conviction of former death-squad leader Emmanuel “Toto” Constant.

“U.S. forces captured lots of documents which proved how Toto Constant’s organization FRAPH was responsible for the death of many people in Haiti,” she told the crowd. “He was working for the CIA. The CIA brought him to the United States. Today we see that they give money more value than people” because Constant was being prosecuted for grand larceny and falsifying business documents rather than crimes against humanity. “We ask for justice for all the people that Toto Constant killed in Haiti,” she said.

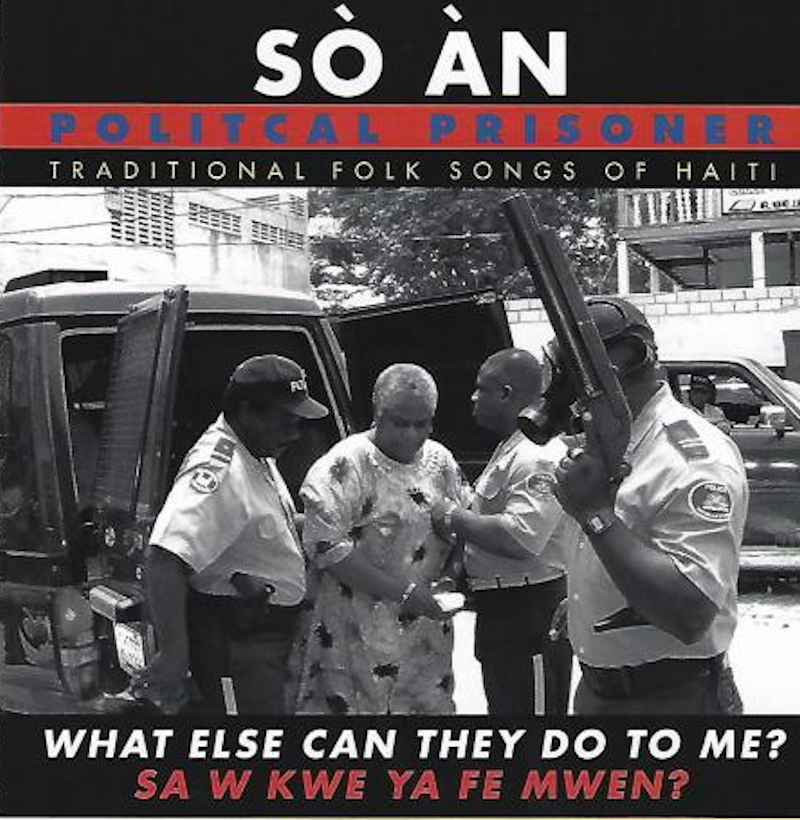

While she was in prison, Crowing Rooster Arts released in 2005 a CD of her songs with her chorale entitled “What Else Can They Do to Me?” In 2007, she recorded another album with Manno Charlemagne in New York, but it was never released.

In 2007, she also attended the hearings of Father Gérard Jean-Juste, who had also been jailed by the de facto regime on trumped-up charges.

But most of Sò An’s efforts were focused on rebuilding the Lavalas Family party and rewriting its charter. In alliance principally with Aristide’s former Prime Minister Yvon Neptune, who was also imprisoned during the coup, and FL’s former Chamber of Deputies President Yves Cristalin, she sought to create a way for the popular organizations which make up the party’s base to nominate their own representatives rather than having Aristide select them, which resulted in mid-level leaders often being unpopular with the party’s rank-and-file.

But Aristide was opposed to this approach, fearing the influence of President René Préval and chaos emerging in the party’s base. Behind the scenes, he delegated Narcisse to counter Sò An’s and Neptune’s initiative. Two rival currents emerged, proposing two different sets of candidates for upcoming elections.

“Two dueling factions of Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s Fanmi Lavalas party are pushing competing plans to reform the FL charter as they jockey for a claim to leadership of the party in advance of the late 2010 presidential elections,” wrote U.S. Ambassador to Haiti Janet Sanderson in a May 29, 2009 secret cable to Washington, obtained by Wikileaks and provided to Haïti Liberté. “Lavalas’s two largest factions look unlikely to resolve their differences anytime soon… The two groups’ public infighting redounds to the benefit of President Préval, who has seen his once formidable opponents squander their energy and credibility on internal disputes.”

Although the FL’s 13th anniversary celebration on Nov. 3, 2009 at the Aristide Foundation for Democracy featured Narcisse and Auguste raising their arms together on the stage in a show of unity, the rivalry continued.

Indeed, Préval capitalized on the FL’s rift to disqualify the party from the 2010-2011 presidential election, with the acquiescence of the U.S. and EU.

Former konpa singer Michel Martelly won that election thanks to aggressive support from Washington. He engaged in a concerted charm campaign to win over Sò An, with a high-profile visit to her Delmas 16 home. Bitter from her Lavalas Family split and grieving from her eldest son Ralph Samedi’s 2011 death from kidney failure (her second eldest son, Jean, died in 1997 from a gunshot; it was never clear if it was murder or suicide), she gave in to Martelly’s overtures and accepted to run for Senator of the West Department in the 2015 elections. Her once loyal followers abandoned her, appalled by her political about-face, and she lost that race.

It was around that time she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Her long-time partner and guitarist Wilfrid “Tido” Lavaud also suffered a stroke. Nonetheless, as she had for years, she continued to prepare meals for poor people in her neighborhood.

But these events all put immense pressure on Sò An, and her health declined. She received two months of medical treatment in Cuba, where she was advised to return. But she decided to remain in Haiti, where the cancer continued its relentless spread. She was hospitalized for a month before her death.

The PHTK has tried to reclaim her memory for their party’s propaganda, much as they did after the December 2017 death of Manno Charlemagne, who had a parallel flirtation with Martelly, creating similar dismay in the Lavalas masses.

But Sò An’s overwhelming legacy remains one of struggle against Haiti’s right-wing forces, although she succumbed to their bribes, flattery, and enticements in her final years.

Tido is now hospitalized in serious condition. The family has not told him, or Sò An’s two older sisters, Raymonde and Alma, about her death for fear that they too might die from the shock. The family is planning to hold Sò An’s funeral with only 20 people in Port-au-Prince on Fri., Apr. 24. The location is not being made public out of concerns for not attracting crowds during the coronavirus epidemic.

“It is heart-breaking for my brothers [Robert and Donald] and I that we cannot travel to Haiti for the funeral because there are no flights,” Réginald Auguste, who lives in Brooklyn, told Haïti Liberté. “We hope we can travel to Haiti this summer after the coronavirus crisis ebbs to do a ceremony.”

Perhaps the best words with which to remember Sò An come from a portion of the statement that she issued from prison.

“While I have been forced to sit in this jail cell, I have also seen the cynicism of some within our party, brought about by this campaign of repression, intimidation, and assassination. I understand their fear as I am myself a victim of this campaign, whose purpose is to destroy our hope and aspirations for building a Haiti where the poor are not simple tools upon which to build dreams of personal empire and wealth.

“I would remind all those who still consider themselves to represent Lavalas and Haiti’s poor majority to remember the lesson of the first occupation of our homeland by the Americans and our great martyr, Charlemagne Péralte [who led the peasant guerillas who fought the U.S. Marines]. Péralte made his peace with the Americans in good faith and disbanded his armed resistance against the occupation only to fall victim to their lies and ill intentions: he was kidnapped and assassinated. A similar fate threatens many Haitians today in Lavalas who believe in our national sovereignty and justice.”

Most of Sò An’s life was dedicated to taking such progressive, anti-imperialist stances. She will be remembered as a combatant for Haitian democracy, justice, and sovereignty, despite the moments of weakness to which she surrendered in her final years.