There are four different phases of contemporary paramilitarism in Haiti: 1) the Tonton Macoutes (officially known as the Volontaires de la Sécurité Nationale or VSN), 1959–1986; 2) the Attachés, 1987–1991; 3) the FRAPH (Front révolutionnaire pour l’avancement et le progrès haïtien), 1992–1994; and 4) the FLRN (Front pour la libération et la reconstruction nationale), 2000–2005.

The size of each successive organization in comparison to its predecessor has decreased. By the mid-1980s, during the late days of the Duvalier regime, the army numbered around 10,000, the police force had around 6,000 officers, and another 36,000 were believed to be in the Macoute paramilitary force, with some of these and others serving as rural section chiefs and their assistants. Following the fall of the Duvalier dictatorship in 1986, as Kim Ives explains “the Attachés (1986–1989) came to number somewhere around 5,000, with the FRAPH numbering maybe slightly less under the [Cédras] defacto regime (1991–1994).”

As Peter Hallward observes, the most recent paramilitary formation, the FLRN (2000–2005), numbered only around a few hundred but then in the months surrounding the 2004 coup swelled to one or two thousand, some of whom were from the disbanded army.

-

The Tonton Macoutes (1959–1986)

The construction of Haiti’s modern military force and the strengthening of its rural auxiliary forces had already occurred under the U.S. occupation (1915–1934). That occupation ended only after these forces could reliably continue the occupation by proxy and, by the mid-20th century, these forces were used at different points to crush rising labor and popular political movements.

With the rise of the authoritarian Duvalierist regime in the late 1950s, the Tonton Macoutes (VSN) were formed as a countrywide paramilitary force to solidify the regime’s rule and violently repress potential dissidents. The VSN was formed at a key historical juncture, when leftist movements were on the rise in the Caribbean region following the Second World War. In reaction, U.S. policymakers sought to prop up the security forces of its allied regimes.

Between 1961 and 1962, the U.S. Marine military training mission provided training and weapons to the VSN, but by 1963, the mission was expelled by François Duvalier when its officials began to disapprove of the VSN’s challenge to Haitian army supremacy. Even still, U.S. officials came to tacitly support the death-squad apparatus that foiled several Cuban-inspired revolutionary invasions and uprisings.

As the regime’s brutal monopolization of power halted the ability of the country’s leftist and democratic forces to advance, it also solidified a violent web of nepotism and networks of patronage that reached from the top to the bottom of society.

Whereas repressive militias had existed in the past, what set the Tonton Macoutes apart is that the Macoute paramilitaries became a much more permanent and institutionalized force, setting up stations throughout the country’s urban and rural communities. Stations in cities and towns across the country could call upon anywhere from a few dozen to a few hundred Macoute paramilitaries. The group’s reproduction in society was tied directly to its operating and profiting as a repressive apparatus and as an ideological mechanism for the Duvalierist state. Similarly, the section chiefs and their assistants, who came mostly from landed peasant families, operated across the country as an arm of the regime. Tens of thousands were tortured and murdered by the VSN, with many others driven into exile as refugees.

As a social group, mostly from poor backgrounds, the Macoutes also included individuals from middle- and upper-class backgrounds who rose to the higher ranks. In an ethnographic study of one Port-au-Prince neighborhood (Bel Air), Michel Laguerre found that initially Macoutes had been gathered from a secret society, a literary association and a group of civil servants. Over time many of its forces came from poor urban and rural communities, the working class and peasantry. Laguerre observed that: “The salaries of the Tonton Macoutes vary depending on their positions in the hierarchy and their connection with officials in the government.” Some Tonton Macoutes worked for city officials or were higher paid if they worked directly for the National Palace. A secret network of informants and police within the Macoutes were remunerated by regime leaders behind closed doors and expected to monitor the force from within.

Some Macoute paramilitaries also served in Haiti’s army at different points in their career – forming a symbiotic relationship with the FAd’H (Forces Armées d’Haïti). As Jean-Germain Gros has explained, in some cases, “the sons of high-ranking Tonton Macoutes, who were not qualified to enter the military academy, or did not wish to submit to rigorous exercises, became officers anyway, after taking crash courses at camp d’application.”

By the 1970s and 1980s, some of the top echelons of Haiti’s military came to control and profit tremendously from transshipment points in the country for the narco-trade. Importantly, following Francois Duvalier’s death in 1971, the U.S. business investment and government aid to his son’s regime, Jean-Claude Duvalier, dramatically increased over the next 15 years, shifting the center-of-gravity of Haiti’s principal mode of production from semi-feudalism with some capitalist inroads, based on small peasant sharecroppers, to a client capitalism, based on assembly plants. These rapid and profound changes to Haitian society occurred alongside rising tensions from below, resulting in the breaking apart of Haiti’s authoritarian political scene. These changes occurred also as U.S. policymakers began to shift toward promoting new polyarchic political models, seen as more stable in the long- term. As such, the U.S. did nothing to stop Duvalier’s 1986 fall from power, while also recognizing his service by providing a C-130 to evacuate him with his fleet of sport cars to France.

The fall of Jean-Claude Duvalier in February 1986 was followed by a military regime which had to accept, in March 1987, a highly popular new constitution. While a victory over the old forces of reaction, the new constitution was also influenced in part by ideologues of Haiti’s bourgeoisie and landed oligarchy. While being forced to give in to some demands of the popular classes, dominant political and economic sectors now sought ways to steer a political transition away from despotism and toward a new bourgeois democracy. Even as the Haitian people mobilized in ways that fostered democratic inroads, powerful forces (such as U.S. government agencies) sought to slow and subvert this forward movement. The Tonton Macoute paramilitary force was disbanded, and the new constitution was promoted popularly on the basis of a clause that barred “zealous” Duvalierists (i.e. VSN leaders) from public office for a decade. These democratic advances would not have been achieved if not for the mass demonstrations and the fact that people were now refusing to accept the violent role of paramilitaries in their communities. Powerful supporters of Haiti’s state apparatus (such as within the U.S. foreign policy establishment) realized they needed to help facilitate a more palatable and stable political climate within the country. While most public and high-ranking supporters of Duvalier were forced out of political office, many of the old order’s networks and allies (though operating under new circumstances) remained burrowed within the state and powerful circles. Even though the Macoute force was formally disbanded, the importance of paramilitary forces would continue on but in a new phase.

-

The Attachés (1986–1991)

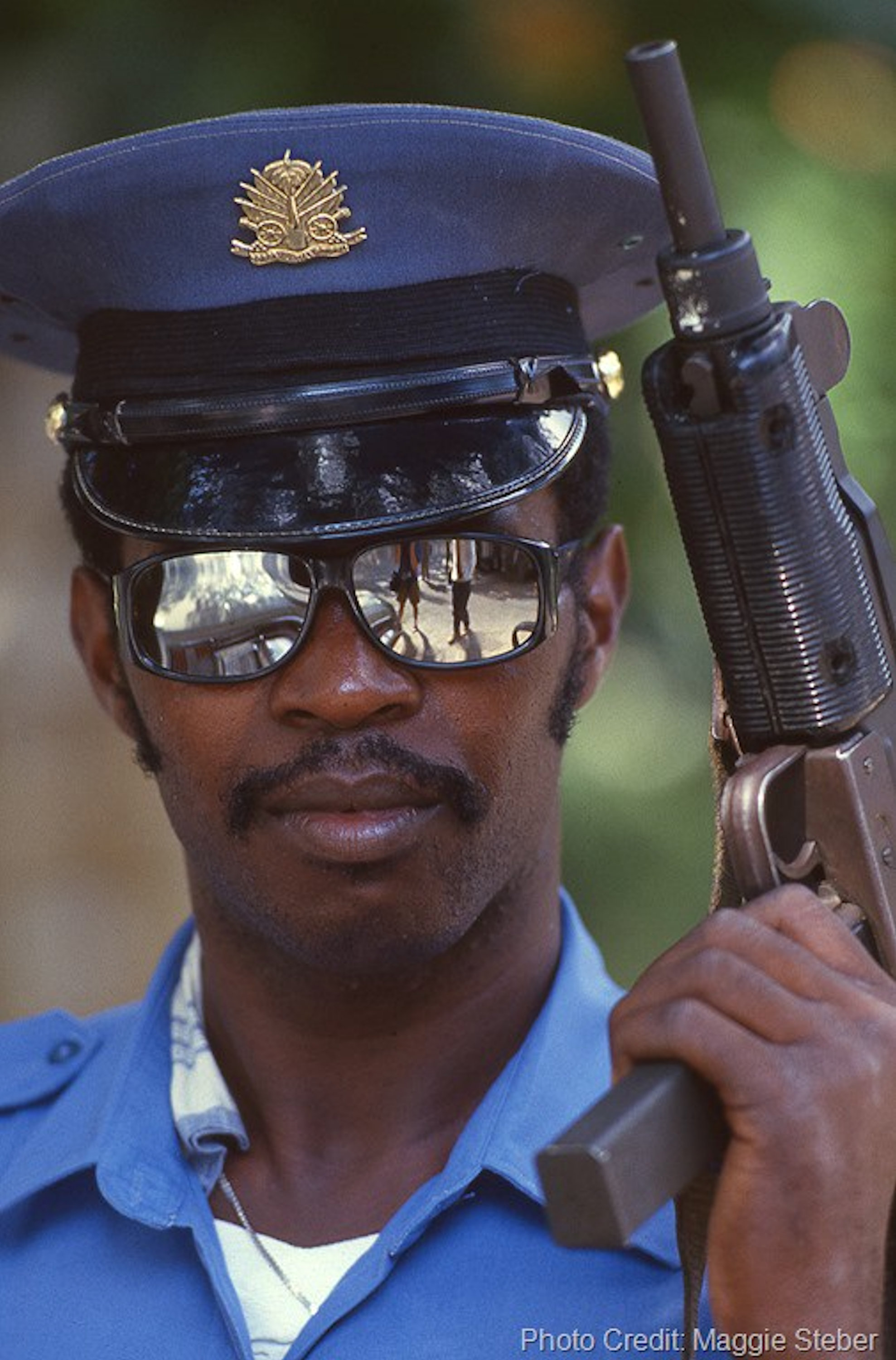

The Attachés, as they were dubbed under the regimes of Generals Henri Namphy and Prosper Avril following the fall of Jean-Claude Duvalier, were decreased-in-size and non-uniformed. These paramilitaries (“attached” to the Police) no longer operated under the regalia and publicized marches that the Duvalier dynasty had bestowed upon them. Nevertheless, they worked even more closely with the police and military (which were institutionally linked), especially because it became increasingly risky for the rightist paramilitaries to operate alone as the population began to mobilize and defend themselves and, in some instances, retaliate. The Attachés, as an apparatus for holding back the country’s burgeoning popular movements, conducted massacres and targeted killings (often operating alongside state forces). Most infamous of these were: the 1986 massacre of 15 people at Fort-Dimanche, the 1987 Jean-Rabel massacre of 139 peasants, the 1987 election day massacre at Ruelle Vaillant in which 34 were killed (with another 60 massacred in the Artibonite alone), and the 1988 massacre of 13 at Saint-Jean Bosco (launched against the church of a young parish priest, Jean-Bertrand Aristide).

After failed attempts at military-run “elections,” significant domestic and international pressure had built pushing for free and fair elections in the country. However, the reactionary nature of the paramilitaries and their sponsors was such that following the first widely hailed fair and free election in the country’s history on Dec. 16, 1990, in January 1991 the Attachés attempted (unsuccessfully) a coup to stop the inauguration of the newly elected government. With this coup attempt having failed and with the country’s re-energized pro-democracy movement catapulting itself and Aristide to political power, the Attachés were forced underground. Some of the paramilitaries left the country, as the military (at least publicly) distanced itself from them. The new constitutional government began to disband the Section Chiefs (chefs de section) and their network of assistants, who were the long-time rural auxiliaries that had enforced the rule of authoritarian governments for generations in Haiti’s countryside and border areas.

The move from dictatorship to democracy needs to be understood in light of the major socio-economic and political changes taking place with the winding down of the Cold War and the onset of the globalist phase of capitalism. Eventually, under growing pressure, both domestically and from abroad (especially from U.S. officials), and with an emergent transnational policy network exerting more influence, political and army elites in Port-au-Prince moved toward a transition process that would be overseen by the so-called “international community.” The plan was for elected governments (elected through the confines of an elite-run polyarchic system) to replace the unelected military regimes of the past. By backing carefully managed elections, U.S. technocrats with a slew of local allies, sought the stability through which they could create a welcoming, long-term climate for global capital. These neoliberal policies were supposed to bring about state austerity measures, privatization of public assets, the liberalization of trade, and the development of export processing zones. Since transnationally-oriented elites could not countenance electoral victories by political currents from the left, they have worked through various institutional apparatuses to promote their local elite counterparts (from among a strata of politicians, professionals, industrialists, agro-industrialists, and subcontractors). Segments of the dominant groups in Haiti, for instance, have undergone a transition from being internationally-oriented (such as being involved in forms of older traditional market activities) toward a transnational orientation (inserted into global systems of finance and production networks functionally integrated across borders). With Haiti’s grassroots popular forces successfully mobilizing in the country’s new open elections, different strategies (deploying both consensual and coercive forms of hegemony) would be needed to usher along an elite dominated transition.

In the 1990 election, a former World Bank economist Marc Bazin had been the preferred presidential candidate of top elites and the U.S. embassy. However, he was trounced in the elections by a social justice activist and former liberation theologian Jean-Bertrand Aristide. This necessitated the next make-over of Haiti’s paramilitary forces, although many figures were salvaged and retreaded from the previous two phases cited.

-

The FRAPH (1992–1994)

Only eight months after the inauguration of President Aristide’s administration in Haiti, in September 1991, the military carried out a coup d’état against his government. CIA officials, Haiti’s military brass, and some within les familles (a small collection of extremely wealthy families that make up the uppermost tier of Haitian society, many of Haitian-Levantine backgrounds) decided early during Aristide’s time in office that his reform agenda would not be tolerated. It then took some months to lay the groundwork for a coup that took place on Sep. 30, 1991.

Aristide’s election represented a challenge to the polyarchy model, as the popular mobilizations and demands did not fit with a smooth elitist-transition to a more consensual form of upper-class rule. The coup then represented both a clumsy attempt by the old order to re-impose itself, and an attempt by some U.S. policymakers to reset the country’s local political dynamics.

The main new paramilitary force came to be known as the FRAPH, a group used across the country to carry out assassinations and intimidation against activists from the Lavalas movement

Following the military coup, people from the “same collection of elites that had been cultivated by the U.S. political aid programs since the 1980s” (Robinson, Promoting Polyarchy) were put in charge of a new de facto regime. Yet, even with these new technocrats in place, the de facto regime failed to gain legitimacy in the eyes of the Haitian people.

As multiple human rights teams and journalists documented, the de facto regime imprisoned and massacred large numbers of youth and pro-democracy activists that organized against the coup.

The military regime relied increasingly on paramilitary forces. Reconfigured at a reduced size, paramilitary forces came out of hibernation. The main new paramilitary force came to be known as the FRAPH, a group used across the country to carry out assassinations and intimidation against activists from the Lavalas movement, many of whom were involved in liberation theology, urban and rural anti-coup organizations, and militant popular organizations. U.S. journalists and filmmakers documented how the CIA’s station chief in Port-au- Prince, John Kambourian, was providing direct cash payments to the FRAPH leadership and working as an interlocutor between the local bourgeoisie, the FRAPH, and the U.S. embassy. The illegality of the coup, the extreme violence and corruption of its enforcers, and the pro-democracy organizing of many Haitians (and international campaigns of solidarity as well as media and human rights reports) resulted in the de facto regime becoming widely and accurately recognized as a pariah and narco-state. Fragmentation among the country’s upper class heightened as some began to distance themselves from the regime. As a warning to bourgeoisie members turning publicly against the regime, democracy advocate and businessman Antoine Izméry was assassinated in September 1993. Faced with the unrestricted and embarrassing violence of a CIA-backed death-squad (and with increasing media attention), the U.S. State Department publicly backpedaled earlier “constructive engagement” with the regime.

While some dominant groups saw the permanent out-in-the-open paramilitary campaign as useful for re-solidifying the old authoritarian order, this clashed with the more sophisticated strategy of many transnational elites seeking a more stable and less brittle system of polyarchy. As William I. Robinson explains: “FRAPH added a new element to the Haitian political scene that served the anti-popular agenda in the short run but complicated the long-term transnational elite agenda for Haiti.”

While the FRAPH became a “well-organized instrument of repression, operating in a death-squad manner to continue the process of decimating popular sector organization, [it] also constituted the political institutionalization of forces bent on preserving an authoritarian political system,” Robinson wrote.

In late 1994, with the de facto regime facing mass demonstrations and increasing international isolation, the Clinton administration and UN intervened, pressuring its leaders to step down. U.S. intervention allowed for the elected government to return to office, but under a set of neoliberal conditions. These included the near elimination of agricultural tariffs, which would have the effect of continuing the destruction of local small-scale/family/peasant agricultural production in Haiti due to the inability of local farmers to compete with U.S. agribusiness. The de facto regime had already stopped enforcing the country’s tariffs, as “imported rice entered as contraband with bribes replacing customs duties.” (Theriot, “To Help Haiti.”) The U.S. and its allies essentially forced the returned government to codify a fact already accomplished on the ground.

The transition though did allow for an end to the paramilitary terror and allowed for Haiti’s popular movements to once again mobilize. Paramilitary groups went underground, with much of their top leadership going into hiding or exile. Haiti’s returned government instituted a truth-and-justice process, which though facing many setbacks, began to hold members of the paramilitary and military accountable for their crimes. As previously documented, a number of paramilitaries and high-profile financiers were arrested and for the first time in Haitian history faced trial and jail time.

In its most popular act, the Aristide government disbanded the country’s brutal army and rural Section Chiefs (both having become deeply entwined with the paramilitaries). Mobekk argues that the demobilization of the country’s military for the time being “removed the threat of institutionalized violence and diminished the possibility of military interference in the democratization process … also decreased the possibilities of organized FRAPH violence, since they had been closely connected with FAd’H.” In spite of this victory, the ex-army, paramilitaries, and their elite backers secretly maintained back channels among themselves. Some backers and top-tier leaders of the paramilitary forces remained active, even if no longer operating directly through Haiti’s state apparatus.

It soon became clear that U.S. officials were not pleased with the newly returned President’s move to demobilize Haiti’s armed forces, promote justice for the victims of paramilitary violence, and build a new police force. U.S. officials opposed Aristide’s preference for a police force made up of civilian trainees. They preferred instead to maintain a large part of the army and recycle other ex-FAd’H, by inserting them into the new police force. Importantly, some of Haiti’s army personnel had for many years held connections with the Pentagon and U.S. intelligence. A UN report concluded that “President Aristide’s decision in January of 1996 to dismantle the FAd’H was met with displeasure by the U.S.,” as the U.S. Defense Department wanted to maintain at least half of the force.

Consequently, the U.S. was successful in pushing dozens of ex-FAd’H, who remained in close contact with the U.S. embassy and intelligence, into Haiti’s new police force. Haiti’s reconstituted government also brought in around 100 ex-FAd’H members that it believed had left their old ways. Among the ex-FAd’H, some would cause significant problems in the years to come.

The disbanding of the military, while hugely popular with Haiti’s poor and securing the government’s stability, also set into motion some new problems. The first was that a portion of the ex-army was unwilling to reintegrate into society, feeling they would lose their privileged social position. Some of these became involved in private security agencies, others went into the private sector, while others continued to be involved in narco-trafficking, with some plotting against the constitutional government (finding benefactors among segments of the elite right-wing opposition). Attempting to manage this situation, UN officials (and, briefly, some U.S. officials) worked with the Haitian state promoting a training and placement program to set into motion a reintegration of ex-army men into Haitian society. However, as Mobekk explains: “The feeling of possessing power cannot easily be substituted, or channeled into retraining.”

Following the country’s first democratic transition of power, with René Préval’s first administration coming to office (1996–2001), there occurred (under U.S. pressure) a heightened insertion of ex-FAd’H into police ranks. A few of these individuals, from middle strata backgrounds, had attended Port-au-Prince’s prestigious upper-class school Saint-Louis de Gonzague, and had received military training by the U.S. in Ecuador.

A lack of resources, low pay, the machinations of the U.S.(which had helped facilitate former FAd’H allies present inside the police forces) and the corrupting influence of narco-traffickers led to continued crises within the police. These consisted of infighting and disorganization within the police, as narco-syndicates benefitted from bribing some within the police to secure their trafficking operations. As Brian Concannon, a U.S. attorney who began working in Haiti on human rights law in the 1990s, points out: at least a third of the police force could be counted on as professional officers loyal to the civilian government. Another third could be bought off or paid to turn their heads, with some of these sympathetic to those advocating for the return of the disbanded military. For the rest, it was less clear where their loyalties lay, with many wanting to avoid risk or waiting to see who would come out on top.

Such divisions appear to have been one factor for the failure of Haiti’s government to stave off a new concerted paramilitary campaign that was unleashed in the early 2000s. The paramilitary campaign benefitted from efforts by local opposition political parties, the U.S., Canada, and France, and officials within powerful international financial institutions (such as the World Bank) to further undermine the elected government.

Next week: the FLRN and Conclusion

(This article was adapted from Sprague-Silgado’s longer, foot-noted article earlier this year in the British scholarly journal, Third World Quarterly.)