Haitians in the Dominican Republic are demeaned, harassed, and victimized in both mundane and extraordinary ways, just like Palestinians in Israel or Latino, Asian, and Muslim immigrants in the U.S..

Pushed out of their homeland by the economic consequences of coups d’états, import dumping, and super-exploitation, officially 751,080 Haitians call the Dominican Republic home. This is 7.3% of the DR’s official population. There are hundreds of thousands of other Haitians who are deemed “illegal” and do not appear in statistics.

“Antihaitianismo,” or anti-Haitian racism, is but one glaring symptom of the Dominican elites’ mind-set, and their state, whose policies resemble apartheid, has a vested interest in persecuting and scapegoating Haitians in the DR and even their Dominican offspring.

“To Improve the Race”

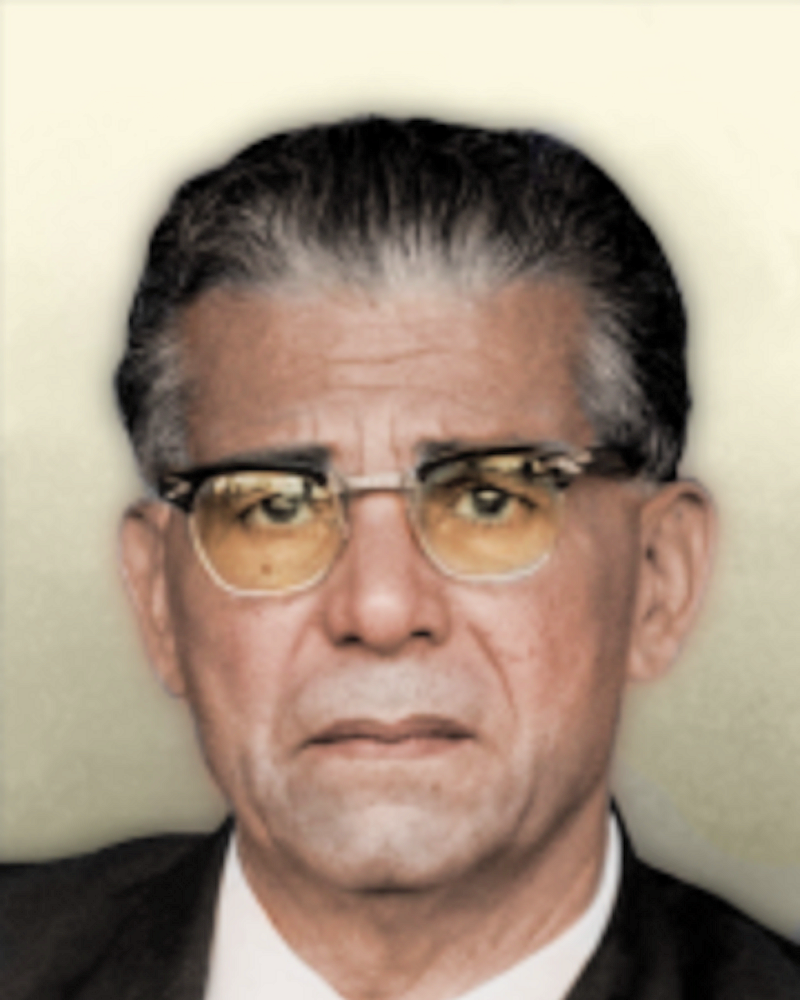

For decades, the Dominican people have been bombarded with both intense and subtle propaganda denigrating “Haitianidad” (being Haitian, often equated with being Black). Both dictator Rafael Trujillo (1930-1961) and his protégé Joaquín Balaguer (periodically president from 1960-1996) depicted Haitians as “the other” and were hispanophiles, exalting Spanish heritage and culture – that is, being white and European.

Military checkpoints line the routes from the Haitian border towards the DR’s interior.

As an example of “casual” anti-Haitianism, some Dominican parents jokingly threaten to send their kids in a sack to a Haitian bogeyman if they misbehave. Haitians are accused of stealing animals, or even children, and sacrificing them. In popular lore and the mass media, Haitians are identified with hunger, infectious disease, political turmoil, and “black magic.”

Imbued with a certain myth of their cultural and racial superiority (although many have African ancestry), most Dominicans have turned their backs on Haitian language, history, and culture. Talk about “good hair” and “improving the race” by marrying someone lighter-skinned is common.

Popular educators from groups like Acción Afro-Dominicana and Agenda Solidaridad work hard to reeducate Dominicans about the Haitian reality and raise awareness of the absurdity and danger of anti-Haitian hysteria.

Ideologues of Hate

Dominican Presidents Danilo Medina (2012-2020) and Luis Abinader (August 2020 to the present) have invested substantial financial and human resources into persecuting Haitians who came to the Dominican Republic. These presidents have engaged in the same practices as their predecessors dating back to Trujillo.

Military checkpoints, one every few miles, line the routes from the Haitian border towards the DR’s interior. National Guard searches of public transportation serve to publicly humiliate Haitian migrants and remind them of their status as unwanted visitors. The Dominican military aggressively searches through Haitians’ luggage and merchandise, mocking their language, dress, and skin color, and demanding that they pay ridiculous fines. Dominican state police have converted crossing the border and traveling into the interior into a business based on bribes. The most aggressive guards carry out illegal deportations and beatings if Haitians do not give in to extortion. Rhetoric about the need to patrol for Haitian arms, drug traffickers, and “illegals” serves as the eternal justification for this aggressivity.

Even Dominican citizens sometimes contribute to this persecution. One Sunday afternoon on a bus returning from the border town of Jimani, I witnessed a young Haitian man being forced from the front to the back of a bus on the charge that he had “el grajo,” or body odor. Dominican passengers waved their hands in front of their noses as if to say that he could not sit close to them. The man was robbed of his right to take the seat he wanted for an eight-hour bus trip.

In counterpoint, Dominicans are trained to be respectful, servile, and obedient to German, Spanish, Italian, and North American tourists. As long as Haitians are viewed as sub-human, they can more effectively be exploited. Racism provides the cloak and justification for their super-exploitation.

“La desmemorización” (The Removal of Historical Memory)

The Dominican state apparatus has assumed the leading role in labeling, stereotyping, and scapegoating the Haitian community. One of the foremost ideologues behind anti-Haitianism was Balaguer, who dedicated his intellectual and literary talents to defaming Haitians. In his book “La isla al revés” (The Island of Dreams), he stomps on the dignity of Haitians, absurdly blaming them for the spread of venereal diseases across the Dominican Republic, among other things. (Prostitution is common in the DR, with its tourist-based economy.) Balaguer stoked Dominican society’s historical paranoia that Haitians will try once again to unify the two countries under one government, as happened from 1822 to 1844. False historical accounts of Haitian rule are still used today to whip up anti-Haitian hysteria. In truth, the Haitian occupation brought freedom to Dominican slaves and broke up the monopoly of land and wealth by the Spanish colonists and Catholic Church. In the words of Dr. Silvio Torres-Saillant, “many marginalized Dominicans lived better with the unification than they did before under Spanish rule.”[1]

Any mention today of the 22 years during which the neighboring nations were united provokes wild tales of vicious Haitian soldiers throwing children into the air and chopping them up with their machetes as they fell. There must be resistance to and deep historical reexamination of this distorted historical memory to rescue the Dominican and Haitian people’s history of solidarity. Haiti never “colonized” the Dominican Republic.

What is Behind the Wall?

As the Haitian people continue to rise up in 2021 against dictatorship and neocolonialism, the Dominican Foreign Minister, Roberto Álvarez, announced that his country has embarked on the construction of a 118-mile wall along its border with Haiti. In his annual 2021 State of the Union address, President Luis Abinader lauded the wall without mentioning once the historic struggle the Haitian people are engaged in. The estimated cost is over $100 million dollars. In the grips of a pandemic, where tourism, construction, and remittances have taken a serious hit, it is shocking that this is Dominican government’s economic priority.

These same mouthpieces of the ruling consensus, who feign concern about the welfare of “the Dominican nation,” are silent when it comes to the class of millionaires who are the nation’s true masters. Ruling families like the Corripios, Bonettis, and Vicinis control over a billion dollars of investments in the central sectors of the Dominican economy like construction, tourism, cacao, energy, and telecommunications.

According to Oxfam, there are 265 millionaires in the Dominican Republic. To give a sense of what it means to be a millionaire in a country affected by widespread poverty and exclusion, a Dominican from the poorest 20% of the country would have to work 214 years to be able to earn what one of the 265 Dominican millionaires earns in a month. The study concludes: “The accumulated wealth of these 265 people is equivalent to 13 times the annual public investment in education, 17 times the public investment in health, or 49% of GDP.” Motivated by political opportunism, far-right careerists like Joaquín Balaguer, Vinicio Castillo, and Pelegrín Castillo have constantly attacked Haiti.

The Haitian people have long been blamed for many things in the Dominican Republic, including disease, unemployment, and social crises. The political actors who nurture these narratives do not want to address the gross class divide in the nation. Haitians provide the perfect diversion and scapegoat.

The two nations do not need a wall; they need economic, educational, and diplomatic bridges of solidarity. When the Haitian and Dominican people build these bridges, it will complete the unfinished revolution that the Mirabal sisters, Caamaño, Mamá Tingó, Orlando Martinez, and so many other Dominican revolutionaries fought and died for.

Danny Shaw teaches at the City University of New York and lived from 1997 to 2001 in the Dominican Republic, where he visits often.

Sources

[1] From a speech at a conference on Dominican Independence at The Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial & Educational Center in Uptown Manhattan in 2016.