(The first of three installments)

The United States has militarily invaded 84 of the 193 nations recognized by the United Nations, and been “militarily involved” in 191 of them, according to the 2014 book America Invades by historians Chris Kelly and Stuart Laycock.

Therefore, one can only observe with incredulity Washington’s outrage, bluster, sanctions, and hypocrisy over the past month (along with the incessant, histrionic barking of its lapdog media) as Russia has invaded Ukraine to stop and rollback the encroachment of the U.S.-dominated North American Treaty Organization (NATO), with thousands of troops and missiles, up to its borders. Furthermore, Russia’s “special military operation” aims to end Ukraine’s eight-year war (which has killed some 14,000 civilians) against its breakaway Donetsk and Luhansk provinces, root out provocative neo-Nazi units at the core of Ukraine’s military, and send a muscled message to U.S. and European imperialism. This comes after years of Russia’s unsuccessful diplomatic pleading for respect of its “red-lines.”

After U.S. Secretary of State James Baker pledged to Russia in 1989 during the collapse of the Soviet Union that NATO would not expand “one inch eastward,” Washington did just that, bringing the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Albania, and Croatia into the military alliance. Since the 2014 U.S.-fomented Maidan coup in Ukraine, Washington has unofficially “NATOized” Ukraine, placing missiles a mere six-minutes flight away from Moscow. Finally, having formed an alliance with China, Russia judged it was time to put its foot down, much as the U.S. did when the Soviet Union placed missiles in Cuba in 1962.

Meanwhile, most Haitians are rooting for Russia in its new game of chicken with the U.S., the actual instigator of and adversary in the Ukraine conflict. This is in part because Haitians have been the victim of three major U.S. military interventions (1915, 1994, 2004) over the past 107 years and harbor deep resentment to this day. “Bay kou bliye, pote màk sonje,” says the Kreyòl proverb. “He who gives the blow, forgets; he who bears the scar, remembers.”

The economic drivers behind the first U.S. Marine occupation are laid out in great detail in Peter James Hudson’s 2017 book Bankers and Empire, extended excerpts of which we published last summer.

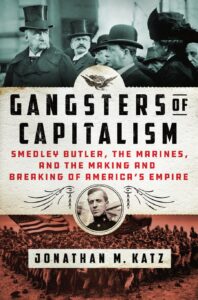

This January, former Associated Press Haiti correspondent Jonathan M. Katz produced a book which nicely complements Hudson’s history of U.S. finance capital’s imperial emergence: Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire (St. Martin’s Press, 2022).

Gangsters chronicles the bloody neo-colonial exploits of Marine Major General Smedley Butler. “From his first days as a 16-year-old recruit at the newly seized Guantánamo Bay, he blazed a path for empire,” the book’s jacket explains, “helping annex the Philippines and the land for the Panama Canal, leading troops in China (twice), and helping invade and occupy Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Mexico, and more. Yet in retirement, Butler turned into a warrior against war, imperialism, and big business, declaring: ‘I was a racketeer for capitalism.’”

For the next three weeks, we will publish extended excerpts from Gangsters’ chapter about Haiti, although the book follows Butler’s career through many other invasions. We encourage readers to learn about those too.

It is important to revisit the history of the U.S. empire’s expansion into Haiti for two reasons. First, it helps to recall and examine in detail the greed which motivated it and racism which laced it. Secondly, the first U.S. invasion of Haiti reveals very different motive forces than those behind Russia’s push into Ukraine today. The former war was fundamentally aggressive, while the latter is principally defensive.

Finally, in his 1935 pamphlet “War is a Racket,” Smedley Butler made observations startlingly applicable to the Ukraine crisis, which has brought us closer than ever to a third world war and nuclear annihilation. “Beautiful ideals were painted for our boys who were sent out to die,” Butler wrote of the First World War, the rhetoric and circumstances of which eerily parallel those of today’s conflict. “This was the ‘war to end all wars.’ This was the ‘war to make the world safe for democracy.’ No one mentioned to them, as they marched away, that their going and their dying would mean huge war profits.”

Kim Ives

(The views, analysis, and opinions expressed in this introduction to the excerpt presented below are those of Haïti Liberté and do not necessarily reflect those of Jonathan M. Katz, the author of Gangsters of Capitalism.)

On Dec. 16, 1914, a pair of U.S. Navy gunships slipped into Port-au-Prince Bay, the gateway to Haiti’s capital. They sat idling for a day, provoking nervous speculation among the city’s residents. The next afternoon, at approximately one o’clock, eight Americans were seen hustling toward the republic’s central bank, the Banque National de la Republique d’Haïti. They were Marines, disguised in civilian clothes. They chose the hour knowing that most people in the business district would be indoors on their lunch breaks, resting from the heat.

The undercover Marines burst into the bank, brandishing revolvers and canes. The Haitians inside were alarmed. For all appearances, the Caribbean republic’s most important bank was being robbed. And in fact, it was: some of the bank’s French and American clerks, apparently in on the plan, handed over 17 heavy wooden boxes, prepacked with gold bars, valued at roughly $30,000 each.

The Marines hoisted the boxes into a wooden wagon waiting outside. Then they rushed back toward the wharf, passing still more undercover Marines posted along the route. The boxes were loaded onto a motorboat and stacked under a weighted cargo net, surrounded by 25 more Marines armed with rifles. In short order, half a million dollars’ worth of Haitian gold — more than half of Haiti’s total government reserves — was aboard the U.S. gunboat Machias, headed for a vault on Wall Street.

Haitians were outraged. “How much was taken? By what rights?” the newspaper Le Matin demanded to know. The robbery was just the most recent example of a century of abuse by foreign powers since Haiti — the world’s first Black-run republic — won its freedom in one of history’s most spectacular events a century earlier: the 1791–1803 Haitian Revolution.

For overthrowing their oppressors and freeing themselves, Haitians had been rewarded by Europe and the United States with exclusion and economic isolation. In 1825, in exchange for belated diplomatic recognition (and under the threat of French naval bombardment), Haiti’s leaders agreed to pay their former enslavers in France a crippling indemnity of 150 million gold francs. To pay it off — which Haiti eventually did, in full — the country’s leaders accumulated even more foreign debt. In 1880, Haiti gave France’s Société Générale a charter for a central bank, hoping it might lead to relieving the burden. In 1910, President Taft’s secretary of state, Philander Knox, had negotiated a new agreement with Haiti in which French, Germans, and Americans would split the bank’s ownership shares.

The Haitian central bank’s new U.S. offices were located at 55 Wall Street, inside the headquarters of James Stillman’s National City Bank of New York (known today simply as Citibank). Supervising the operation was new City Bank vice president Roger Leslie Farnham — the journalist-turned-operative last seen as Sullivan & Cromwell’s point man in the Panama conspiracy. Within a few years, Farnham began advising Wilson’s secretary of state, William Jennings Bryan, on Haitian matters.

Bryan was eager for the advice. By the summer of 1914, Haiti’s cash-strapped government was in turmoil. The foreign-run Banque Nationale added to the burden by speculating with government revenues, destabilizing the Haitian gourde, and withholding funds from the Haitian state by prioritizing reimbursements to foreign backers when the government coffers were bare. As unrest spread, a series of unfortunate accidents befell Haiti’s presidents: One was killed when an ammunition depot exploded and destroyed his National Palace. The next died soon after, purportedly of poisoning. A succession of military coups followed.

The opening for more direct U.S. involvement in Haiti came thanks to a shocking turn of events in Europe. In July 1914, the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was assassinated while visiting his colony of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The political killing set off a showdown between competing European alliances that resulted in what would become known as the First World War. With France and Germany now busy killing each other across the Atlantic, Farnham saw a chance to take over Haiti’s central bank entirely. It was he who convinced Bryan to approve the heist. Once Haiti’s gold reserves were stashed away safely on Wall Street, Farnham got hungry for more.

Throughout late 1914, the Navy Department drew up detailed plans for an invasion and occupation of Haiti

Farnham knew that Bryan distrusted banks. (In 1896, the agrarian populist had famously accused East Coast bankers of intending to “crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”) So he appealed to Bryan’s overarching fear of getting sucked into the new European war. The banker showered the State Department with a stream of implausible rumors about German designs on Haiti, which, had they in the least been true, would have augured a Kaiserreich colony 600 miles off Florida.

That was the stick. The carrot was a promise that, if a U.S.-friendly puppet president were to be installed in Haiti, politically connected corporations including United Fruit would set up shop there. Most important, Farnham suggested to Bryan, a client government in Port-au-Prince could ensure U.S. control over the Môle Saint-Nicolas — the harbor facing Guantánamo across the Windward Passage, which was now a key sea lane for traveling to and from the recently opened Panama Canal.

Throughout late 1914, the Navy Department drew up detailed plans for an invasion and occupation of Haiti, down to where to build the baseball fields that off-duty Marines would use and where to buy rum. Taking over foreign cities had become so old hat for the U.S. military that it was developing an actual template: some of the plans were simply repurposed from the recent invasion of Mexico, with instructions reading: “rewrite letter inserting port au prince for vera cruz, mexico wherever it appears.”

The looting of the Banque Nationale proved a crucial step. The newspaper Le Matin observed, apparently fulsomely, that an “appalled public” was left to rely “on the wisdom of the [Haitian] government, which, firmly in its rights, will know how to defend the interests of the Republic.” Bryan’s dismissive reply to that government — in which he called the heist “merely a withdrawal of funds by the authorities of a private bank” — did not quiet the simmering rage.

Disgraced by the incident, yet another Haitian president was forced to resign. Farnham and Bryan were pleased with his replacement, a 56-year-old general named Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, who signaled openness to an arrangement with the United States — possibly a Dominican-style “receivership” in which a U.S. bank would take over the Haitian customs system.

But Sam would not get a chance to cut a deal. Accusing the new president of being a “thief” and “traitor” who “wants to give up our customhouse to the Americans,” a nationalist physician named Rosalvo Bobo channeled public outrage into an uprising in the north of Haiti. In response, Sam ordered the arrest and execution without trial of suspected sympathizers in the capital. Relatives of the slain prisoners, bereaved and furious, stormed the partially reconstructed National Palace. They chased Sam to the nearby French legation and killed him. Then they threw his corpse into the street, where it was dismembered by the mob.

Having destabilized Haiti’s government through an armed robbery, Woodrow Wilson then used the murder that came in its wake as a pretext to invade. The following day, Jul. 28, 1915, Wilson ordered Rear Admiral William Caperton aboard the USS Washington — which had been waiting off the coast of Haiti for months — to seize control of Port-au-Prince. By 5:45 p.m., 330 Marines and sailors were ashore just outside the capital. They marched in double columns into the center of the city, shooting and killing a handful of Haitian resisters. Port-au-Prince fell without a single American casualty.

Though Bobo fled the onslaught to nearby Cuba, his rebels in the north — known as “Cacos” — would not be defeated so easily. Caperton radioed for more Marines. Col. John Lejeune, acting in the absence of the commandant, ordered an advance base brigade of two regiments to deploy to Haiti.

Littleton Waller, the “Butcher of Samar” [in the Philippines], would command all U.S.ground forces in the Black Republic. To lead the First Battalion of his First Regiment, Waller chose his favorite Quaker Marine [,Smedley Butler].

In the fall of 1915, Smedley Butler set out with Waller and a Marine battalion across northern Haiti to dismantle the Caco resistance. They traveled on a fortified train through the fertile plains surrounding Cap-Haïtien, the republic’s main northern port and second-largest city. In the near distance rose the jungle-covered peaks of the Massif du Nord.

In letters to his “Dear Old Dad,” Thomas Butler, Smedley explained the purpose of the mission. Word was spreading across Haiti that the Americans had installed a new puppet president: a milquetoast former senator named Philippe Sudré Dartiguenave. Wilson’s new secretary of state, Robert Lansing, had dictated the terms of a new treaty to put Haiti’s entire economy under the control of a U.S.-appointed financial adviser. Anti-American sentiment was surging. Demonstrations broke out across the country. Caco insurgent attacks against the Marines increased in frequency and severity.

Some of the Navy brass had proposed bribing the Cacos into submission. Waller wanted a more violent response. The colonel, Butler told his father, “is of the old-fashioned school that believes the way to end a row with a savage monkey is to first go into the region or territory occupied by that monkey and find out how savage he is.”

The roots of Littleton Waller’s racism ran deep. Both sides of his tangled family tree had played instrumental roles in turning his home state of Virginia into a powerhouse of enslavement. His 18th-century ancestor Col. John Waller was a pioneer of the trade; among the people he claimed as property was “Toby” Waller, the African man identified in Alex Haley’s 1976 novel, Roots, as Kunta Kinte. Waller’s maternal grandfather was Virginia governor Littleton Waller Tazewell, who, after a bloody 1831 insurrection led by the enslaved rebel preacher Nat Turner, spent the rest of his life campaigning for the expulsion of Black people from the United States. Among those killed in Turner’s rebellion were the wife and children of a slaver named Levi Waller, likely a distant relative.

Waller, the Marine, was fiercely proud of that family history. (His full name, which he was not shy about using, was Littleton Waller Tazewell Waller.) As a teenager in the 1870s, he served in the Norfolk Light Artillery Blues, an ex-Confederate militia likely charged with enforcing “anti-vagrancy” laws meant to intimidate freed Black citizens. Waller saw his experience enforcing racial apartheid at home as the highest qualification for his work in the Caribbean. “I know the nigger and how to handle him. The same quality is going to be needed in San Domingo,” he told Lejeune as the Haiti operation began. One can imagine Waller smiling under his imperial mustache as he used the slave name of the country he was invading, as his ancestors and their French counterparts had done before him.

Terrified of Haiti’s capacity to inspire, white U.S. elites did everything they could to demonize the country and suppress the memory of its revolution.

Haiti and the idea of Black freedom it represented had played foundational roles in U.S. history. The loss of Saint-Domingue had ended Napoleon’s dream of a vast French American empire, forcing him to sell his planned breadbasket — the 530 million–acre Louisiana territory — to Thomas Jefferson at fire-sale prices. That new territory, and the fight over whether and how to extend slavery into it, helped foment the Civil War. Jefferson in turn lived in fear of “another Saint Domingo” consuming him, perhaps in his plantation bed outside Charlottesville.

And he was not alone: The future Commandant Lejeune grew up in Pointe Coupee, Louisiana, a town that carried the memory of a failed 1795 uprising in which enslaved African-Americans had tried to win their freedom by burning planters’ homes, before they were captured and beheaded. A leader of that uprising, an enslaved man named Jean Baptiste, had recruited others by promising: “We could do the same here as at Le Cap” — meaning the city later called Cap-Haïtien, which the Haitian revolutionaries had burned two years before.

Terrified of Haiti’s capacity to inspire, white U.S. elites did everything they could to demonize the country and suppress the memory of its revolution. But the model of self-emancipation through armed revolution and the reality of Black people in positions of national power continued to inspire uprisings throughout the American South, including Nat Turner’s.

At the Virginia Secession Convention of 1861, soon-to-be Confederate Gen. Henry L. Benning warned that, once slavery was abolished, America would have “black governors, black legislatures, black juries, black everything. . . . We will be completely exterminated, and the land will be left in the possession of the blacks, and then it will go back to a wilderness and become another Africa or Saint Domingo.” (Fort Benning, home of the reconstituted School of the Americas, is named after him.)

The Marine Corps was shaped by those histories as well. One of the most celebrated moments in Corps history was the 1859 arrest of the radical white abolitionist John Brown at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, by Marines under U.S. Army Col. Robert E. Lee. (A painting of Brown’s arrest hung in the Library of the Marine Corps when I was last there.) The failed raid, which has been called a dress rehearsal for the Civil War, was meant to inspire an uprising against slavery along the lines of the Haitian Revolution. One of Brown’s jailers reported that in the days before his hanging, the devout abolitionist consoled himself by reading a biography of the Haitian Revolution’s most famous leader, Toussaint Louverture.

(From Gangsters of Capitalism by Jonathan Katz. Copyright © 2022 by the author. All rights reserved. Click here to order the book.)