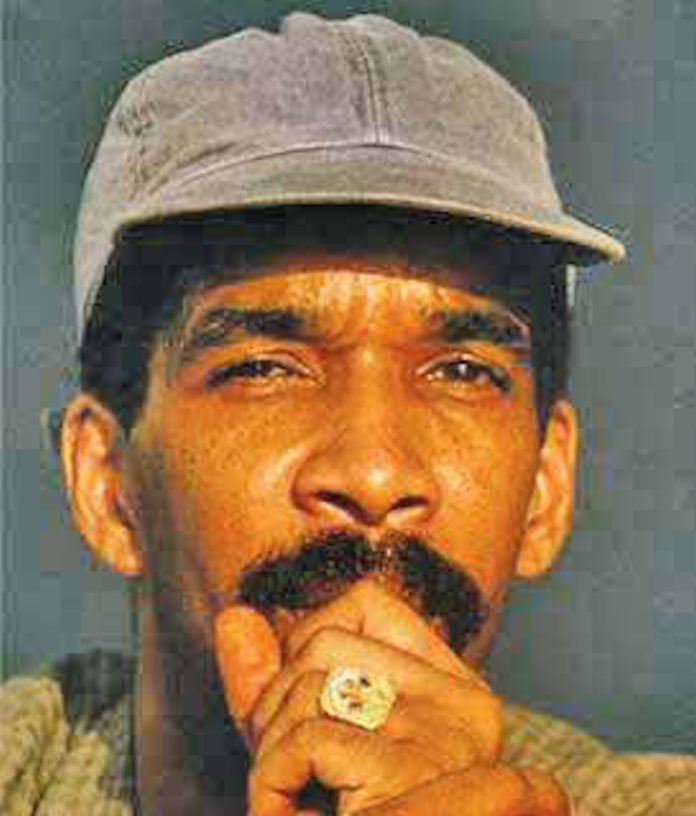

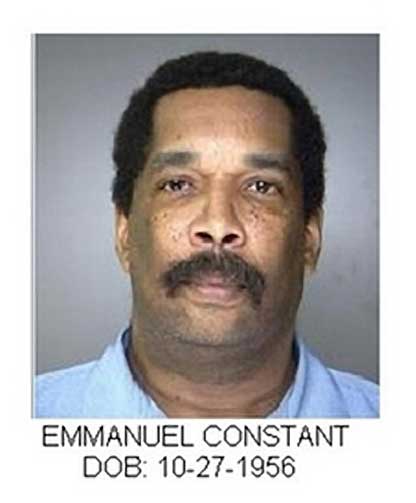

Alarm and indignation are growing over former CIA agent and death-squad leader Emmanuel “Toto” Constant’s deportation by the U.S. back to Haiti last month.

Haitian police arrested Constant when he stepped off the plane on Jun. 23, but now it remains to be seen if Haitian authorities will bring him to justice for the many crimes against humanity of which he is accused.

“Is Haiti’s justice system up to the job” of retrying Constant? That was the question asked by a Jul. 5 Washington Post editorial.

Constant was convicted in absentia in 2000 for crimes against humanity committed when his Revolutionary Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti (FRAPH) helped carry out a massacre in the Gonaïves’ neighborhood of Raboteau in April 1994. But now he is entitled to a new trial.

The Post already recognizes that “Haiti’s judicial system is fragile at best, and [President Jovenel] Moïse’s own commitment to human rights and justice is highly suspect: He named another man convicted in the Raboteau massacre to a top position in the country’s reconstituted army — an institution that itself has a bloodstained history. If Mr. Constant goes free or is subject to a trial manipulated in his favor, it will be a conclusive sign that impunity once again has triumphed over rule of law in Haiti.”

We’ve heard such pious concerns before… from the U.S. Embassy in Haiti, no less.

In secret diplomatic cables provided by the media organization WikiLeaks to Haïti Liberté in 2011, we learn that the de facto government assured the U.S. Embassy that it would not release another convicted FRAPH leader, Louis-Jodel Chamblain, the death-squad’s #2.

“The Gonaïves prosecutor and the chief judge of the Gonaïves court have connived in an effort to get Chamblain released illegally, but the IGOH [Interim Government of Haiti] has pledged not to do so,” reported the U.S. Embassy’s Chargé d’Affaires Douglas Griffiths in a May 13, 2005 cable classified “Confidential.”

Bear in mind, the IGOH of Prime Minister Gérard Latortue was patently installed by Washington following the Feb. 29, 2004 coup d’état it engineered against former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Latortue was Washington’s puppet.

After riding triumphantly into the capital with the armed “rebels” who helped overthrow Aristide, Chamblain turned himself in to Latortue’s government in April 2004. In a sham overnight trial, he was acquitted of the September 1993 murder of Lavalas businessman activist Antoine Izméry, but his 2000 conviction in absentia for involvement in the 1994 Raboteau massacre still stood.

Pierre Espérance of the National Network for the Defense of Human Rights (RNDDH) confirmed for the embassy a United Nations report “that the chief prosecutor and chief of the court in Gonaïves had collaborated to produce a release order for Chamblain,” wrote Griffiths. “He said the chief prosecutor (Commissaire du Gouvernement) for Port-au-Prince would have to approve any Chamblain release, and had given assurances that he would not do so. Charge [Griffiths] raised this issue with Prime Minister Latortue May 11. Latortue assured us that Chamblain would not be released, saying Minister of Justice [Bernard] Gousse agreed with him on this. He repeated this twice, saying Chamblain would not be released as long as he was Prime Minister.”

But three months later, on Aug. 11, 2005, Chamblain was released from prison. He walks freely and prominently in Haiti to this day.

Could “Toto” Constant also walk? It’s very possible, given that Haiti’s justice system today is even more corrupt and dysfunctional than it was 15 years ago.

In a May 25, 2005 secret Embassy cable, U.S. Ambassador to Haiti James Foley related the May 20 presentation of Thierry Fagart, the UN Human Rights Representative, to the “Core Group,” the pro-U.S. ambassadors to Haiti.

“Fagart warned the Core Group that there was good reason to believe that Louis Jodel Chamblain might be freed even sooner following the May 3 decision by the Supreme Court to annul part of the Raboteau case,” Foley wrote.

On that date, the Supreme court had issued “an unexpected ruling” which overturned “on procedural grounds, … the convictions of the 15 people who were actually present during the [Raboteau trial] proceedings,” Griffiths had explained in his May 13 cable. Griffiths had opined that “there may indeed be technical merit to the Supreme Court’s decision” but worried that “it has nonetheless reinforced perceptions that the judiciary under the current government [of Gérard Latortue] is biased against Lavalas partisans and more focused on procedural matters than on justice.”

Furthermore, “legal experts were puzzled at the decision to go further and order the accused set free,” Griffiths continued. “Normal procedure would have been for the Supreme Court to annul the lower court ruling and then either re-try the case(s) itself or send them back to the Gonaïves court for (proper) retrial. The Supreme Court did neither, instead ordering the prisoners freed if there were no other cause.”

One of those let off the hook by the Supreme Court was former Haitian Army Lt. Col. Jean-Robert Gabriel, the very man who now holds “a top position in the country’s reconstituted army,” as the Washington Post lamented this week.

In his May 20, 2005 presentation to the Core Group, “Fagart concluded that it was evident that the justice system was under the influence of ‘some bad characters’,” a remark which MINUSTAH Chief Juan Gabriel Valdès “labeled ‘the understatement of the year’,” according to Foley. (The MINUSTAH or United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti was the first of two international military forces which occupied Haiti from 2004 to 2019.)

Another factor working in Constant’s favor is the disappearance of about 60,000 pages of internal FRAPH documents seized by U.S. troops after they occupied Haiti in September 1994. They captured the trove in an early October 1994 raid on FRAPH’s Port-au-Prince headquarters. After a concerted legal and political campaign by the Haitian government and human right groups, President Bill Clinton finally agreed to return the documents (even though many names were reportedly redacted) to Haiti seven years later, on Jan. 20, 2001, his last day in office.

“But he extracted a promise from President René Préval that they would only be used in a court case,” explains Brian Concannon, an attorney who worked for years prosecuting the FRAPH in conjunction with Mario Joseph of the International Lawyers Office (BAI) in Port-au-Prince. “Préval, and subsequently Aristide, took the promise very seriously – they did not want to give the U.S. the slightest chance to claim that Haiti hadn’t kept its word. So both said the BAI could only get a look at the documents if we went in with a judge. For three years we tried to get a judge to go in with us, with no luck.”

With 20/20 hindsight, Concannon now regrets that the BAI had not persisted more forcefully. “The urgency had passed with the completion of the Raboteau trial,” he said. The BAI had been the principal architect of that prosecution. “We had other cases where the documents would have been helpful, but they were all fairly early in the proceedings, so there was not a deadline.”

The BAI might have thought it had more than three years to get to the documents, but then the Feb. 29, 2004 coup intervened. The last thing Concannon knew of the documents, “they were in a locked room in the basement of the National Palace on Mar. 1, 2004.”

Nobody seems to know what happened to them after that. Were they hidden or destroyed by the armed “rebels” led by Guy Philippe and Louis Jodel Chamblain after they entered Port-au-Prince on Mar. 1, 2004, or by the U.S. Marines who secured the National Palace at about the same time? Or did the Latortue government do something with them? Were they recovered after the 2010 earthquake partially destroyed the National Palace?

“We at the BAI intend to write a letter to Jovenel Moïse asking for the whereabouts of the documents and that they be turned over to Haitian prosecutors for Constant’s trial,” Mario Joseph told Haïti Liberté.

“The question of Justice appears to mean nothing for the current leaders as high profile criminals and lawbreakers, one way or another, are going free, circulating in the streets without concern while their victims continue to cry out for justice,” wrote Pierre Espérance’s RNDDH on Aug. 13, 2005, two days after Chamblain’s release. “Fourteen years after the coup d’état against then President Aristide in 1991, RNDDH remarks that several of those implicated in crimes committed during the three years that followed continue to benefit from blatant impunity… For RNDDH, last week’s release of Louis Jodel Chamblain is a slap in the faces of the victims of the Raboteau killings, the victims of [the] Cité Soleil [massacre in 1993], and all the victims of the 1991-1994 coup d’état years.”

Now, almost 29 years after the 1991 coup d’état, Espérance points out that Haiti’s justice system is even more crooked and ineffective.

“Toto Constant has his government in power,” he told Haïti Liberté. “We can’t be overly optimistic. We have to remember that with everything that happened during the 1991-1994 coup d’état, Michel Martelly was a part of it.” Martelly is a konpa musician who, as Haiti’s president from 2011 to 2016, mentored and hand-picked Jovenel Moïse to be his successor.

However, at the same time, Espérance points to Article 7 of the Apr. 7, 1998 judicial reform law passed under President Préval which states that “the crimes committed from September 30, 1991 to October 15, 1994 are and remain without any statute of limitations.” (Le Moniteur # 61, Aug. 17, 1998).

For Espérance, the documentary evidence used to condemn Constant in absentia during the 2000 Raboteau trial will be thoroughly sufficient to convict him again.

“A Haitian prosecutor’s order on [Jul. 24] to jail death squad leader Emmanuel Constant is a promising first step toward long-delayed justice for Constant’s victims,” wrote Concannon and Joseph in a Jun. 25 op-ed in the Miami Herald. “But actually achieving justice will require many more steps by both Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse and President Trump, and their administrations. Our 25 years of experience pursuing cases against Constant and other human-rights violators leads to deep concerns about whether either government will take those steps.”

“The United States is Moïse’s international ally, and it should use that relationship to ensure that Haiti makes sincere efforts to prosecute Constant,” the op-ed concluded. “The United States should also compensate for the opportunity missed in 2000 by providing financial and technical support to the prosecution, and the extensive information on Constant’s activities that its intelligence services collected. Anything less would convert justice delayed into justice denied.”