(Français)

A prominent Haitian businessman and a top U.S. Embassy official urged UN occupation troops to attack a crowded Haitian slum, fully expecting that “unintended civilian casualties” would occur, according to secret diplomatic cables provided by WikiLeaks to Haiti Liberté.

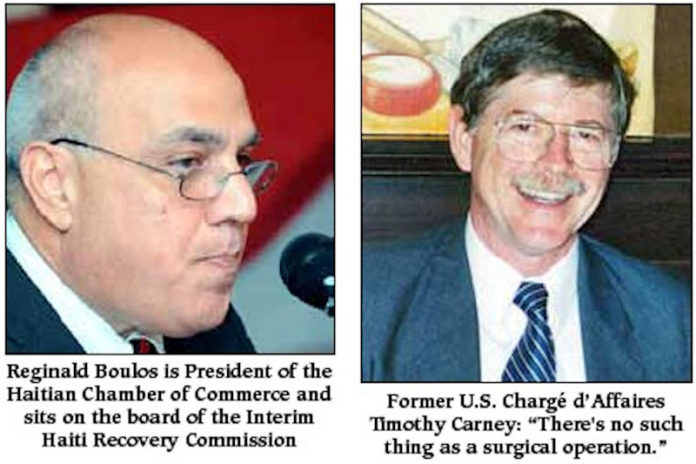

Haitian Chamber of Commerce President Reginald Boulos, now a voting member of the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC), met with U.S. Embassy Chargé d’Affaires Timothy Carney on Jan. 4, 2006. Both the Embassy and Haiti’s private sector leaders were upset with the UN mission’s reluctance to launch a violent crackdown on armed groups in Cité Soleil, a vast waterside slum in Port-au-Prince.

At the meeting, “Boulos argued that MINUSTAH [or UN Mission to Stabilize Haiti, as the UN force is known] could take back the slum if it were to work systematically, section by section, in securing the area.”

Carney “cautioned that such an operation would inevitably cause unintended civilian casualties given the crowded conditions and flimsy construction of tightly packed housing in Cité Soleil,” according to the Jan. 6, 2006 cable, which Carney wrote.

Rather than suggest an alternative that would avoid “inevitable” civilian deaths, Carney continued, “Therefore, the private sector associations must be willing to quickly assist in the aftermath of such an operation, including providing financial support to families of potential victims.”

“Boulos agreed,” saying “that he and other groups were prepared to go in immediately with social programs and social spending,” the cable said.

Carney says that he has no regrets “whatsoever” about the advice he gave Boulos and the UN

The battle for Cité Soleil continued for the next year and a half, producing scores of “unintended civilian casualties.” Today, Carney, now retired, says that he has no regrets “whatsoever” about the advice he gave Boulos and the UN, although he admits to learning that “there’s no such thing as a surgical operation.”

Also at the meeting between Boulos and Carney were Rene-Max Auguste, president of the American Chamber of Commerce, Gladys Coupet, president of the Haitian bankers association, and Carl Auguste Boisson, president of the petroleum distributors association.

The private sector leaders also “pleaded with the Charge for the USG [U.S. Government] to provide ammunition to the police,” and “Boulos began reading off a specific list of ammunition.” But Carney said the police needed more training, not ammunition.

Six days later, Boulos complained to an NPR reporter, “Please understand that we appreciate the work that MINUSTAH is doing so far, but it’s not enough.” He alleged that there had been a “massive distribution of weapons over the last two weeks in Cité Soleil,” adding that gangs are able to “pick up people, kill people and go back inside, and nobody can go after them.”

As Haiti Liberté has previously reported, Boulos took it upon himself to arm the de facto government’s police force, which violently repressed protests demanding exiled President Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s return, killing scores of demonstrators and bystanders.

Haitian business magnate Fritz Mevs told the U.S. Embassy that Boulos had “distributed arms to the police and had called on others [in the private sector] to do so in order to provide cover to his own actions,” according to another WikiLeaked cable (see Haïti Liberté, Vol. 4, No. 49, Jun. 22, 2011).

Andy Apaid, Haiti’s foremost sweatshop owner, was a leader, along with Boulos, of the Group of 184. The so-called “civil society” coalition, spawned and supported by the U.S. government’s National Endowment for Democracy (NED), helped lead a destabilization campaign against Aristide until his ouster in a 2004 U.S.-backed coup d’état.

A Jul. 24, 2006 cable confirms press reports that Apaid financed an anti-Aristide gang in Cité Soleil led by Thomas Robenson, alias Labanyè, a gang-leader who defected from the Lavalas movement to the pro-coup camp before he was killed by his own lieutenants.

Carney was U.S. Ambassador to Haiti from 1997 to 1999. He later became Chairman of the Board for the Haiti Democracy Project (HDP), a right-wing pro-coup think-tank co-founded in 2002 by Reginald Boulos’ brother, Rudolph. Carney left HDP to become U.S. Chargé d’Affaires in Haiti from August 2005 to February 2006. He is now Vice-President of the Clinton Bush Haiti Fund, established after the Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake.

The military campaign to crush the armed resistance groups in Cité Soleil, which Boulos and Carney discussed, eventually did succeed, but resulted in many “unintended civilian casualties” as Carney predicted.

It had begun on July 6, 2005, when UN troops mounted a massive assault on the slum, firing over 22,000 bullets in about seven hours and killing coup resistance leader Emmanuel “Drèd” Wilmer (see Haïti Liberté, Vol. 4, No. 49, Jun. 22, 2011).

Of the 27 people who came to a Doctors Without Borders hospital with gunshot wounds that day, three-quarters were women and children. Cité Soleil residents told a labor delegation from San Francisco and journalist Jean Baptiste Jean Ristil that MINUSTAH had indiscriminately fired on their homes, killing women, children and infants. The death toll was at least 23, and possibly as many as 50, according to the delegation.

Haitian journalist Guy Delva “saw seven bodies in one house alone, including two babies and one older woman in her 60s.”

U.S. Ambassador to Haiti James Foley admitted in a Jul. 26, 2005 cable obtained by Professor Keith Yearman through a FOIA request, “It remains unclear how aggressive MINUSTAH was, though 22,000 rounds is a large amount of ammunition to have killed only six people [the UN’s official death toll].”

“The foreigners came in shooting for hours without interruption and killed 10 people,” Johnny Claircidor, a Cité Soleil resident, told Reuters after another bloody MINUSTAH operation in Dec. 22, 2006.

“They came here to terrorize the population,” said resident Rose Martel, referring to the police and U.N. troops, reported Reuters. “I don’t think they really killed the bandits, unless they consider all of us as bandits,” she said.

Some 300,000 people live in Cité Soleil’s tiny shacks and houses lining narrow alleys and streets. Many MINUSTAH military forays into Haiti’s slums caused scores of deaths in “collateral damage” from 2005 through 2007.

Cité Soleil’s citizens remain stigmatized to this day by outsiders. The area is routinely labeled as a “red zone” (meaning “not to be visited”) for foreign aid workers.

The seaside slum was one of the most-affected areas in the capital when a cholera outbreak reached Port-au-Prince last fall. The water-borne illness can kill a person within hours. Some bodies lay in the street for days before being picked up, while the Doctors Without Borders hospital was overwhelmed.

The epidemic continues throughout the country, surging whenever rainfall increases. A new six-month cholera Rapid Response Project is being launched, funded by UNICEF and led by the International Rescue Committee in consultation with other water- and sanitation-oriented humanitarian organizations.

The project specifically excludes Cité Soleil from its “list of areas for intervention” due to “security issues,” according to UN Cluster meeting notes obtained by Haiti Liberté.

The purse strings to billions of dollars in humanitarian aid pledged for Haiti’s “recovery” are currently controlled by the IHRC. Boulos is one of 14 voting Haitian members; the other 14 voting members are representatives of foreign governments and international banks.

In a “fact versus fiction” press sheet, the IHRC claims it is “an unprecedented agency in that it has given Haitians a seat at the decision-making table and a strong voice in dictating the course that their nation takes towards short-term recovery and long-term prosperity.”

Boulos was never elected to his “seat at the decision-making table” but was named to it by Haiti’s “business community,” which has one vote on the IHRC board, as does Haiti’s Prime Minister. The appointment was fortuitous for Boulos because he “continues to harbor short-term and long-term ambitions to become prime minister and otherwise exercise key influence in Haitian politics,” explains a Dec. 20, 2005 cable by Carney entitled “Reginald Boulos Aims to Engineer Préval’s Defeat.”

The cable describes another meeting with Carney where Boulos explained his efforts, which proved unsuccessful, to “engineer” the defeat of former Haitian President René Préval in a Feb. 7, 2006 presidential election.

“Boulos believes that a second Préval presidency would be a ‘disaster’ for the country,” Carney wrote, and that “Préval was responsible for gross abuses of law and order during his presidency and could not be trusted.”

Furthermore, “Boulos confirmed that Préval had made a special effort to reach out to him,” the cable continues, “but that Boulos had resisted those overtures. Boulos remained deeply skeptical that Préval had altered his approach to governance [from his 1996-2001 term] or would improve his performance as president.”

Carney “cautioned that such an operation would inevitably cause unintended civilian casualties given the crowded conditions and flimsy construction of tightly packed housing in Cité Soleil.”

Boulos also accused Préval of “support of gang leaders and widespread corruption within his government” and warned Carney that “Préval may be too weak not to allow Aristide and his circle back into Haitian politics.”

Despite his efforts, “Boulos acknowledged his disappointment that after three months of negotiation he had been unable to form a more solid [political] alliance to oppose Préval,” Carney wrote.

Carney appreciated Boulos, whom he described as “refreshingly straightforward and candid.” He knew both Reginald and his brother Rudolph, who was for three years a Senator for Haiti’s Northeast province until he was ejected from the Senate in 2009 when his colleagues learned that he had lied in denying that he was a U.S. citizen, which made him ineligible for the post.

Asked in a telephone interview last month if he had any regrets about approving of an assault on Cité Soleil instead of finding an alternative, Carney replied “none whatsoever.” Asked if he expected innocent people to be hurt or killed in the UN troops’ take-over of Cité Soleil, he said that was in “the back of my mind, sure” and that he knew “yes, there would be consequences including deaths and injuries but the situation required the reestablishment of security.”

He added that “one of the things that you learn, perhaps not as quickly as you should in this business, is that there’s no such thing as a surgical operation.” Nonetheless, when asked if he felt it was necessary to violently crackdown on the gangs, knowing there would be collateral damage, he replied, “absolutely, no question.”

Carney criticized the first MINUSTAH leader, Chilean diplomat Juan Gabriel Valdés, for his “belief that none of the Latin American troops would ever fire on bad elements in Cité Soleil,” asserting that “he was proved wrong, as [Valdés’ successor] Edmund Mulet demonstrated several months later, when MINUSTAH did clean out Cité Soleil after Préval’s re-election” in 2006, overcoming Valdés’ “reluctance… to engage.”

The former U.S. diplomat also believed that the government of de facto Prime Minister Gérard Latortue “was clearly an unusual structure” but that it was “constitutional” and “had the necessary authority… to take measures with MINUSTAH to ensure law and order everywhere in the country including in Cité Soleil.”

One of Haiti’s foremost Constitutional and human rights lawyers, Mario Joseph, who heads the Office of International Lawyers (BAI), scoffs at this claim. “The Latortue government was clearly and completely unconstitutional,” he said. “The Bush administration and other powers behind the 2004 coup concocted a Tripartite Commission and a Council of Sages, which have nothing to do with the Constitution. They took power through a violent coup and then they cooked up a legal ruse to cover their crime.”

Carney said he “did know much of [Haiti’s] business community” and admits that “there’s definitely a huge predatory element still there.” He maintained close contact with Haiti’s pro-coup business leaders even when he was not in the U.S. Embassy, saying he “did talk at length with Andy Apaid of [the] Group of 184 just before Aristide was forced out” on Feb. 29, 2004.

“We always knew it, but finally the WikiLeaks cables confirm it,” said Tony Jean-Thénor of the Miami community group Veye Yo, founded by the late Father Gérard Jean-Juste, when shown the cables cited in this report. “The U.S. Embassy meets with members of Haiti’s bourgeoisie to plot against the people, even armed attacks, and then they try to pose as the saviors.” Ironically, “these same bourgeois end up deciding the country’s future although they never get in that position by a transparent vote from the people. It is always by a coup, a trick election, or being appointed by a foreign power.”

[…] reported by Haiti Liberté, Boulos also took it upon himself to arm the de facto regime’s police force, which violently […]