In June 2020, nine armed groups from Port-au-Prince’s poorest neighborhoods formed an alliance called the “G-9 Family and Allies.” Their spokesman, Jimmy “Barbecue” Cherizier, announced on Jun. 10 that the coalition’s launch was the beginning of “an armed revolution” against Haiti’s “stinking, rotten, corrupt system” serving the bourgeoisie, which was split in backing two rivals. One faction of the bourgeoisie, he explained, supports the clique surrounding President Jovenel Moïse, and the other faction backs his political opposition, headed by outspoken lawyer André Michel and former senator Youri Latortue, both of whom backed the 2004 coup d’état against President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

“The G-9 is not working for the regime, and the G-9 was not created by and is not working for the opposition,” Cherizier said. “It was created to never again have robberies, rapes, and kidnapping in our neighborhoods… but also for the ghettos to get their due,” schools, clinics, hospitals, services, running water, infrastructure, and “all the security which the rich neighborhoods get.”

The bourgeoisie has always cynically used people from Haiti’s slums as cannon fodder in their battles for political control of the state, Cherizier has explained in many radio interviews and YouTube videos. He vows that the poor masses will no longer fight among each other for the benefit of ruling class rivalries; they will only use their weapons to fight and throw off “the system” which is using, repressing, and impoverishing them.

Cherizier is a former 14-year veteran cop who was fired in December 2018 for not responding to a summons from his superiors.

The Demonization of the G-9

Dozens of G-9 “militants,” cheered on by hundreds of slum residents, marched through Port-au-Prince on Jul. 6, 2020.

The spectacle of many armed and organized youths firing their weapons in the air and declaring a “revolution” against the “system” threw terror and panic into the hearts of Haiti’s bourgeoisie and Washington.

“Haiti is not a banana republic where scoundrels, delinquents, and criminals can do whatever they want,” declared Justice Minister Lucmane Délile on Jul. 9 as he returned from abroad. He called the march an “extremely serious” development. “We will not accept this type of comedy in bad taste. I am asking the Haitian National Police [PNH] to do everything in their power to track these guys down like wild animals because that’s what they are, wild animals. They must get what they deserve as delinquents and criminals.”

Délile, a pro-coup actor from 2004, knew before his return to Haiti that he was going to be fired. In a ballyhooed government release of long-time pre-trial detainees, as Justice Minister, he had slipped very recent prisoners onto the list of those to be freed, causing a scandal. Also, in his Jul. 9 airport speech, he claimed that he alone could and would have stopped the G-9 march, effectively humiliating the Prime Minister and President.

So, the same day, Délile was, in fact, fired by presidential decree (Le Moniteur, #114 Jul. 9, 2020) and replaced by Rockefeller Vincent, the former director of the Unit for the Fight against Corruption (ULCC). The dismissal is often cited as the ultimate proof – however, circumstantial – of Moïse government support for the G-9.

“They have tried to buy us. But you can’t struggle against a system if you are taking money from it.”

That interpretation has been taken up by other “tools of the system,” as Cherizier calls them, seeking to demonize Cherizier and the G-9: journalists.

Insight Crime, a Washington, DC and Medellin, Colombia-based “think-tank and media organization” supported by the CIA-cutout National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and billionaire George Soros’ Open Society Foundations, published an often referenced article on Jul. 23, 2020 entitled “Is Haiti’s G-9 Gang Alliance a Ticking Time Bomb?”

“The G-9 alliance has reportedly benefitted from strong ties to the government of President Jovenel Moïse,” the article states, calling Cherizier the front’s “mastermind… tasked with enforcing the state-sponsored alliance.”

“The gang leaders are seemingly free from persecution so long as they help keep the peace in the neighborhoods they control,” the article continues. “In exchange, Moïse’s government has found in them loyal foot soldiers quelling insecurity, stamping out opposition voices, and shoring up political support across the capital.”

The author, Parker Asmann, even states without prudent adverbs, like “reportedly” or “seemingly,” that “the government is using the gangs to repress the opposition.” He offers no proof of the charge.

On Aug. 14, 2020, the Washington Post took up the campaign against Cherizier and the G-9 with the article “In Haiti, Coronavirus and a Man Named Barbecue Test the Rule of Law.”

Although long-time Haiti-hand co-author Ingrid Arnesen actually met with Cherizier, contributing to a slightly more nuanced piece, the article continues the same vilification.

“Cherizier and members of his consolidated gang are extorting businesses, hijacking fuel trucks, and kidnapping professionals and business owners for exorbitant ransoms as high as $1 million,” the article states, confounding Cherizier, a kidnapping opponent, with other groups from Village de Dieu and Grand Ravine clearly engaged in abductions for ransom. (In April 2020, before the G-9’s formation, Cherizier had even threatened in a video to mobilize 19 other policemen to make Village de Dieu “as I need it to be,” that is, free of kidnappers. “Izo,” the leader of Village de Dieu’s Five Seconds Base, replied: “We could go to Barbecue’s neighborhood too.”)

Another trope, particularly used by the bourgeois opposition’s leftist followers, is that the Haitian government’s National Commission for Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration (CNDDR) organized the “gangs” into the G-9 and pays them. The CNDDR’s spokesperson, Jean Rebel Dorcénat, categorically denies the charges. “I never said that I asked the gangs to unite,” he told the daily Le Nouvelliste, which had previously reported that he did.

Dorcénat also dismissed accusations that the G-9 is working for the government. “G-9 members have let me know that they are not supporting anyone,” Dorcénat told the daily, then asked: “If the government does not take into consideration the demands of the G-9 in their neighborhoods, why would the G-9 be at its service?”

Cherizier vs. the Human Rights “Tools of the System”

“They call us gangs and cry that we have guns,” Cherizier said in a Jul. 11, 2020 interview. “There is no bigger gang than that Syrian-Lebanese* mafia bourgeoisie which has taken the nation hostage. And no-one has more guns than they have. They have all the money, and we have none. They call us scoundrels and bandits, think we have no brain, and think they can do with us as they wish. They have tried to buy us. But you can’t struggle against a system if you are taking money from it… They can use their money to kill me, but I don’t need the money of those people. Today, diaspora, it’s on you that we are relying to return to this country, to invest in it. The bourgeoisie doesn’t invest here. They just suck the wealth out and send it to their houses and children overseas. But we ask you, diaspora, to bring what you can. This struggle is your struggle.”

Indeed, many Haitians across its diaspora, and across Haiti, are roused by Cherizier’s call, charisma, and courage. Others are scared by his ferocity or uncritically accept the reports of Haitian human rights groups like the National Network to Defend Human Rights (RNDDH) and the Open Eyes Foundation (FJKL), which are both close to the U.S. Embassy and the empire’s umpire Human Rights Watch (HRW) and were the first to paint him as responsible for the 2018 La Saline massacre.

“We have to denounce the phony human rights organizations, these political human rights organizations, which we have in this country,” Cherizier declares. “We have to invite some international organizations to come and investigate these groups here, for us to see if they too are tools of the system.”

Indeed, it is not the first time that human rights groups have run afoul of “gangs” and revealed themselves to play a political role, much as HRW and Amnesty International often do. In 2004, RNDDH accused the Aristide government of carrying out a “massacre” with its “gangs” in La Scierie, an area of the town of St. Marc. The assessment, which was later discredited, was based on a clash between two of the town’s popular organizations (“gangs”): Balewouze, which was pro-Aristide, and Ramicos, which was anti-Aristide.

Indeed, much of the political struggle in Haiti over the past two decades has been carried out by young toughs from the lumpen-proletariat in Haiti’s proliferating slums. In 2002-2003, as they defended the Aristide government, they were branded as “chimères” or ghosts. In 2004-2005, as Cité Soleil “gang” leaders like Dread Wilmer, Amaral Duclona, “Evans” and “Belony” resisted the coup d’état against Aristide and the ensuing foreign military occupation, they were castigated as “bandits” (as Charlemagne Péralte and his Caco guerrilla fighters were also stigmatized by U.S. Marines during the 1915-1934 U.S. military occupation of Haiti.)

Divisions within the Police

The struggle between haves and have-nots has seen gang warfare and kidnapping in many other countries throughout Latin America, particularly in Mexico, Colombia, and Brazil. Some Washington-backed repressive governments do use paramilitaries to carry out their terror and repression, particularly in Colombia, which also has police specialists to fight kidnapping. Indeed, the U.S. Embassy in Haiti arranged to have a team of anti-kidnapping experts flown in from Colombia to advise the Haitian police.

But therein lies another problem. The PNH itself is rent with divisions and dysfunction.

First there is the unusual appointment of Léon Charles as chief of police last November. After 15 years out of the country and stationed as a diplomat in Washington, DC, Charles was brought back to Haiti to replace Normil Rameau, who had only served 15 months of the usual three year term of a police director. Charles had carried out ruthless repression during his own 17 month stint as police chief in 2004-2005, but was ousted because he either fostered or could not curtail corruption and indiscipline, U.S. diplomatic cables obtained by Wikileaks show.

On top of that, Charles’ appointment by Moïse completely disregarded the usual chain of succession in the PNH hierarchy, injecting anger, resentment, and discord in the police leadership.

Furthermore, there is a struggle between rank-and-file police officers and the top brass. Just this past week, the officers heading the Haitian National Police Union (SPNH) were all fired because of their suspected links to a dissident police group, Phantom 509, which has carried out the storming of prisons and other violent actions, in which two policemen were killed this week.

“Gangs” and the Lumpen-Proletariat in the Class Struggle

While his critics have oddly branded him a collaborator of Jovenel Moïse, Cherizier says his political sympathies and models lie more with the Lavalas currents in Haiti today. He said he greatly admired “the Aristide of 1990″ as well as strident Jovenel Moïse-foe, former Aristide protégé, and outspoken senator Moïse Jean-Charles “if he would disassociate from the rotten opposition.” (Cherizier even denounces foremost opposition leader André Michel for his leadership role in the NED-supported “Group of 184″ coalition, which spearheaded the coup against Aristide in 2004.)

“I don’t know if we should call ourselves the true children of [Jean-Jacques] Dessalines, or children of [Alexandre] Pétion, or children of Capois LaMort,” Cherizier said, referring to leaders of Haiti’s 1804 revolution. “But we have one word to tell the world: we love Haiti, and we have to fight to change this system…. We don’t just need people who have arms although it is true that no revolution is made without arms, and … arms are the symbol of our resistance. We need anybody, doctors, lawyers, professionals, who can contribute to this struggle… We will put down our arms when we finish fighting against this stinking, rotten, corrupt system, which gives five families the power, the monopoly, the right to import rice, sugar, flour, iron, give electricity, as well as install the presidents, senators, and deputies.”

“we have one word to tell the world: we love Haiti, and we have to fight to change this system.”

In short, what appears today as a three-way struggle between the Moïse regime, opposition, and “gangs,” is in fact a two-way fight. Not the foolish, absurd characterization of a government-gang alliance against the bourgeois opposition and Haitian masses demanding that Jovenel step down, as the Constitution dictates.

Rather it is a two-way battle for economic justice, democracy, and sovereignty between Haiti’s heavily lumpenized proletariat and an infinitesimally small ruling bourgeoisie, which has fooled, sacrificed, and massacred them for too long.

In 1895, British Fabian socialist science fiction writer H.G. Wells published The Time Machine, in which the protagonist travels forward in time to the year A.D. 802,701. There he discovers a naïve, child-like race of human descendants called the Eloi, who live a luxurious and care-free existence, frolicking and eating fruit from trees during the day. But they pass the night in terror because another race of human descendants, the Morlock, come up occasionally from underground and kidnap them. In the Morlock’s dark subterranean world, the protagonist finds all the machinery that makes the paradise aboveground possible. It is Wells’ thinly-disguised allegory of the distant future of capitalism’s bourgeoisie and proletariat.

In their 1848 Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels described the lumpen-proletariat as “the dangerous class, the social scum,” which “is here and there thrust into the [progressive] movement by a proletarian revolution; [however,] in accordance with its whole way of life, it is more likely to sell out to reactionary intrigues.” For Marx, it is an “industrial reserve army” and “relative surplus population,” which many times survives off crime, large and petty, and serves often to keep wages low and break strikes.

But in the past century and a half, prominent revolutionary thinkers, beginning with Lenin, have begun to recognize the lumpen-proletariat’s revolutionary potential. Mao Tse-tung called the class “brave fighters but apt to be destructive,” concluding that “they can become a revolutionary force if given proper guidance.”

Amilcar Cabral faced in 1960s Guinea-Bissau a situation very similar to Haiti’s today. He described a “rootless” group which “might easily be called our lumpen-proletariat, if we had anything in Guiné we could properly call a proletariat.” The group consists “of a large number of young folk lately come from the countryside, and retaining links with it, who are at the same time beginning to live a European sort of life. They are usually without any training and live at the expense of their petty bourgeois or laboring families.” Nonetheless, Cabral’s PAIGC “concentrated particular attention” on this “rootless” lumpen-proletariat, and “they have played an important part in our liberation struggle.”

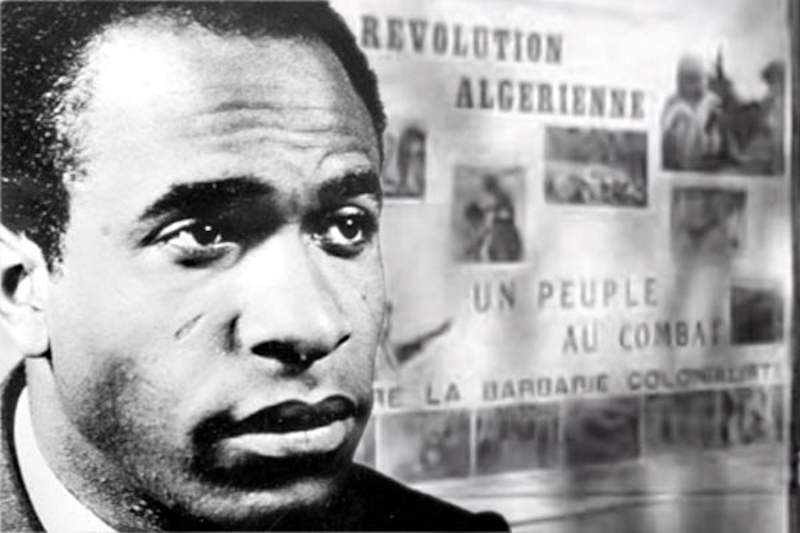

But it was the brilliant Martinique-born Algerian revolutionary theorist Frantz Fanon, who truly grasped the lumpen-proletariat’s revolutionary potential. In a post-colonial neo-colony like Haiti, “the key classes providing support for the revolution, for Fanon, are (1) the peasantry and (2) the lumpen-proletariat, though for either class to struggle with success they must unite with ‘urban intellectuals,’ a small number of whom ‘go to the people’,” explained Peter Worsley in the article “Frantz Fanon and the ‘Lumpen-proletariat.’” (Ironically, the title of Fanon’s most famous work, “The Wretched of the Earth” – Les damnés de la terre – was apparently culled from a poem by Jacques Roumain, the founder of Haiti’s Communist Party.)

The Future of the G-9

Currently in Haiti, the G-9 seems not to be developing into a functioning alliance, but rather fading, although Cherizier is working hard to create and maintain order in the once-feuding coalition. One Haitian analyst said: “It now seems not to be becoming a real organization, but more of a slogan.” The Mar. 12 killing in Village de Dieu of four police officers by the Five Seconds Base, which is not a G-9 member or “ally,” could cause a rift with Cherizier in Delmas 6. “Members of the G-9 must not engage in kidnapping or other kinds of crime,” he said. “We are trying to stop crime so people can live in peace.” However, Cherizier has not declared – at least not yet – that he intends to clean up Village de Dieu, as he said last year.

Cherizier has also been careful not to burn his bridges. He has declared that not all bourgeois, journalists, politicians, or human rights workers are bad. “There are honest, well-meaning ones among them, who side with the people,” he says. And he appeals to Haiti’s diaspora for financial, political, and material support and expertise. Even Village de Dieu’s “Izo,” the villain of the hour, has regretted the killing of the four police officers, held a televised funeral for them in Village de Dieu (he did not return the bodies to their families for “mystical reasons”), and called for dialogue rather that further fighting and bloodshed.

“It is clear that the living conditions of the gang leaders tend to push them to sell out to reaction, but there is nothing to indicate that they cannot do the opposite,” explained a Jul. 1, 2020 Haïti Liberté editorial. “So if they want to go another direction, let’s take them at their word and give them the benefit of the doubt. All those who would like to see the people of the oppressed neighborhoods have a minimum of peace should have only one position: to support them or even to accompany them to achieve this project. And this is what the inhabitants of the working-class ‘Grand-Ravines’ district did, greeting the [G-9] idea with cries of: ‘We want peace! We want peace!’ The settler masters always repressed their rebellious slaves by calling them bandits when they fought to free themselves from their domination.”

*Many refugees from the Mideast migrated to the Caribbean following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century. Over the last century, they have become some of Haiti’s most prominent bourgeois families, prompting some Haitians to use an ethnic and racialist (but by no means scientific or completely accurate) description of Haiti’s ruling class.

Great information shared.. really enjoyed reading this post thank you author for sharing this post .. appreciated

You deserve a star, outstanding.

I admire your work.

I just like the helpful information you provide in your articles

I like the efforts you have put in this, regards for all the great content.

I like the efforts you have put in this, regards for all the great content.

Interesting

Well-written

Black Lives Asia’s initiatives are fostering a sense of unity and solidarity among diverse communities.

Thank you for this well-structured and insightful post. It’s evident that you have a thorough understanding of the topic, and your explanations are clear and concise. Keep up the great work!

Engaging and thought-provoking, I thoroughly enjoyed reading it!

From start to finish, your content is simply amazing. You have a talent for making complex topics easy to understand and I always come away with valuable insights.

Keep up the fantastic work!

Keep up the amazing work! Can’t wait to see what you have in store for us next.

I just wanted to take a moment to express my gratitude for the great content you consistently produce. It’s informative, interesting, and always keeps me coming back for more!

great article very very thanks

Cool that really helps, thank you.

Keep up the fantastic work!

Thank you so much

Best article, wonderfull..

Your writing is so eloquent and persuasive You have a talent for getting your message across and inspiring meaningful change

Keep up the fantastic work!

Your posts are so beautifully written and always leave me feeling inspired and empowered Thank you for using your talents to make a positive impact

Keep up the fantastic work!

Keep up the fantastic work and continue to inspire us all!

This is exactly what I needed to read today Your words have given me a new perspective and renewed hope Thank you

I’m so impressed with your knowledge on this topic. You clearly did a lot of research.

Keep up the fantastic work and continue to inspire us all!

This article is a treasure trove of information. I am impressed by the level of research that has supported your viewpoints, and I appreciate how everything has been articulated concisely and coherently.