(Français)

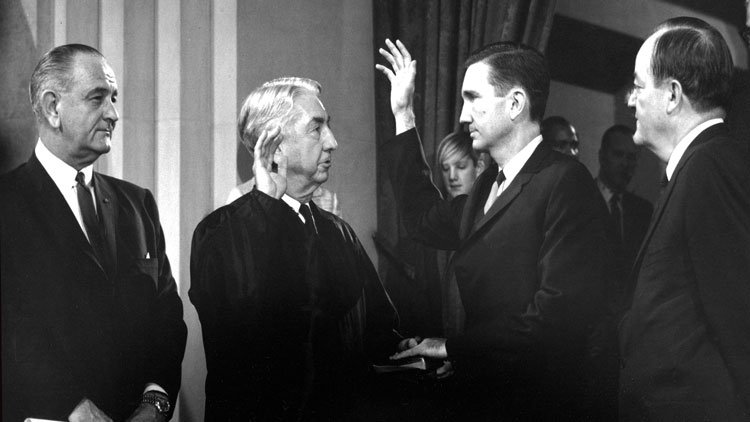

“It seems that, for the rest of my life,” Ramsey Clark said at the funeral of a U.S. revolutionary in 2005, “I will always be introduced as the former U.S. Attorney General.”

However, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson’s top lawyer from 1967 to 1969 will above all be remembered as one of history’s most prominent anti-imperialist, human rights, and peace activists, earning the love, respect, and admiration of millions around the globe.

After years of declining health, Ramsey Clark, 93, died peacefully at his Manhattan apartment on Apr. 9, 2021. He was born on Dec. 18, 1927 in Dallas, Texas, where he was raised.

A Solidarity Emissary

As part of his life’s mission to right wrongs, Ramsey brought his fame, credibility, and solidarity to over 120 countries, from Palestine to Cuba, Iraq to Nicaragua, and South Africa to Panama. But one nation to which he traveled often and had a very special bond was Haiti.

After Ramsey was fired by Republican President Richard Nixon (whose 1968 campaign had specifically targeted Ramsey and whom the Democrats blamed for their candidate Hubert Humphrey’s loss), he returned to a private law practice and made two unsuccessful bids to be the Democratic Party Senate candidate for New York State during the 1970s.

But his 1972 trip to North Vietnam, in defiance of a U.S. government travel ban, began a practice which came to define his life: decades of international solidarity excursions where he’d bring to a nation targeted by U.S. aggression the gravitas and support of a former Washington high official.

This role became all-consuming after he allied in 1989 with the Workers World Party (WWP) to form the Independent Commission of Inquiry on the U.S. Invasion of Panama. He led a delegation to Panama to uncover the true costs of that illegal war. The U.S. claimed only about 500 Panamanians died; Clark’s Independent Commission estimated the figure at least six times higher, over 3,000.

Two years later, on Sep. 30, 1991, the Haitian Army carried out a bloody coup d’état against President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who’d been elected in a landslide 10 months earlier. Three months later, in mid-December 1991, Ramsey Clark, in conjunction with Haïti Progrès newspaper and WWP, led the first large delegation to Haiti to investigate the coup as part of the newly formed Haiti Commission of Inquiry into the September 30th Coup d’État, fashioned after the successful Panama inquiry. The delegation’s investigation was featured in the acclaimed 1992 PBS documentary produced by Crowing Rooster Arts, Haiti: Killing the Dream.

Delegations to Haiti

Ramsey Clark had first visited Haiti as a U.S. Marine in 1946. He took on several Haitian clients with cases against the Duvalier dictatorship at his small but influential law firm at 36 E. 12th Street in New York during the 1970s and 1980s. Then he met Ben Dupuy, the founder of Haïti Progrès and leader of the Committee against Repression in Haiti, in New York in the early 1980s. He spoke at several demonstrations against the Duvalier dictatorship and in support of Haitian refugees.

After the dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier’s fall on Feb. 7, 1986, Ramsey traveled with Dupuy and another Haitian leader, Paul Adolphe, to Haiti to hold a press conference, the first by Haiti’s leftist exiles, at the Holiday Inn in March 1986, which also included Father Gérard Jean-Juste and future presidential candidate, lawyer Gérard Gourgue.

Following the ground-breaking 1991 delegation, Ramsey Clark took part in several other events to fight the on-going coup in Haiti. He traveled to several American cities as well as Montreal, Canada, where he spoke to huge audiences. He also met with Aristide when the exiled president visited Washington, offering his suggestions on how to aid the resistance to the coup.

After Aristide’s Oct. 15, 1994 return to Haiti, in November 1994, Ramsey traveled with the late Center for Constitutional Rights founder and lawyer Michael Ratner and lawyer Deborah Jackson to investigate human rights under the U.S. military occupation of Haiti, which began in September 1994.

“The coup continues,” Ramsey declared at the Haiti Commission delegation’s Dec. 2, 1994 press conference at the Oloffson Hotel in Port-au-Prince. “”The government must begin prosecutions, and yesterday is not too soon.”

“There is no effort at all to prosecute the thugs who made the murders of the coup,” Ratner added during the press conference. “The longer the criminals go unpunished the more likely that the people will take justice into their own hands. People want to know where is justice. Is it under a rock somewhere?”

Upon hearing the press conference over the radio, President Jean-Bertrand Aristide called it a “a strong cup of coffee” with regard to the crying need for justice following the coup. It led to the formation of the International Lawyers Office (BAI), which continues to prosecute human rights crimes in Haiti to this day.

The delegation’s investigation and findings were the subject of a 1995 Haiti Films documentary entitled “The Coup Continues.”

Washington did not allow Aristide to recoup the three years he spent exiled from 1991 to 1994. President René Préval was sworn in 1996 and quickly began to sell off, wholesale and piecemeal, Haiti’s state enterprises – flour mill, cement plant, telephone and electricity companies – as dictated by the U.S. and International Monetary Fund (IMF).

As a result, Haitian unions became engaged in a fierce struggle against privatization and for workers’ rights. In February 1997, Ramsey Clark led another “Emergency Workers Rights Delegation,” organized by the Haiti Support Network (HSN), which included Haitian unionist Ray Laforest from New York and Dominican unionist Angel Dominguez from Miami.

The delegation met with unions from the public enterprises threatened with privatization, such as Electricity of Haiti (EDH), the telephone company (TELECO), the post office, and the airport.

“The policies that are now being placed in position in Haiti, which are forced on the people of Haiti by foreign governments, primarily the government of the United States of America, by the IMF, by the World Bank, promise a disaster for the people of Haiti,” Ramsey said at a Feb. 21, 1997 press conference at the Holiday Inn. “The idea that foreigners can impose some type of new economic structure on the people of Haiti that is going to benefit them economically is a moral outrage and a falsehood. You [the Haitian people] are being forced for the benefit of foreign capital to sell the last assets the people really have. That privatization is grand larceny, it’s major theft. They are taking valuable assets from the people, for the people and by the people, and selling them to foreign capital so they can charge you higher prices for reduced service.”

In May 1998, Ramsey Clark attended, along with Ben Dupuy and Jean-Bertrand Aristide, an “International Conference on the Ownership and Control of the Media” in Athens, Greece, sponsored by the Andreas G. Papandreou Foundation. Ramsey Clark delivered a speech on “Media Manipulation of Foreign Policy.” Aristide spoke on “What the Media doesn’t print: Neoliberalism and structural adjustment policies.” Dupuy gave a talk entitled “The Attempted Character Assassination of Aristide.”

The Second Coup Against Aristide

In early 2004, as Washington-supported paramilitary, civil, and political fronts sought to again overthrow President Jean-Bertrand, who had been massively reelected in 2000 and returned to power in February 2001, the HSN and Ramsey Clark planned another delegation to Haiti to counter the right-wing assault at the end of February 2004. However, a few days before the delegation was to depart, Ramsey was hit by a car while crossing the street near his Manhattan home, breaking his foot, ankle, and nose. The delegation had to be postponed.

After the second coup d’état against President Aristide on Feb. 29, 2004, the revived Haiti Commission of Inquiry, led by Clark, joined with the Boston-based New England Coalition for Human Rights in Haiti to lead a joint delegation of 11 people to Haiti in September 2004 to investigate human rights violations and to meet with grassroots organizations and political prisoners, including former Prime Minister Yvon Neptune, former Interior Minister Jocelerme Privert, and singer-activist Annette “So Anne” Auguste.

The delegation included former U.S. Army Capt. Lawrence Rockwood, who was court-martialed at Ft. Drum in 1995 for trying to protect Haitian prisoners after deploying in Haiti on Sep. 19, 1994. Ramsey had been his attorney.

The delegation also included Haitian-American HSN member Karine Jean-Pierre, who later worked for the Obama White house as a Labor Department liaison and now serves as White House Deputy Press Secretary to Jen Psaki since January 2021.

“The history of Haiti will break your heart. Knowing it, the weak will despair, but the caring will strive to break the chains of tragedy.”

“We conducted over two dozen interviews with Lavalas Family and popular organization militants, as well as non-engaged Haitian citizens,” the two groups wrote in a joint statement for a Sep. 6, 2004 press conference at the Holiday Inn. “It is clear that lawlessness is being used to consolidate both the military and police forces and the political power of a de facto government which was established following the Feb. 29th coup d’état, in which Haiti’s democratically elected president was kidnapped. The repression we have observed here is solely and clearly designed to take power back from the democratically elected representatives of the people and restore that power to Haiti’s traditional ruling groups: foreign corporate interests, the comprador bourgeoisie, and landed oligarchy.”

Also in September 2004, the International Action Center (IAC), which Ramsey founded, published “Haiti: A Slave Revolution,” a book of essays by many authors about Haiti. “The history of Haiti will break your heart. Knowing it, the weak will despair, but the caring will strive to break the chains of tragedy.” Those were the opening lines of Ramsey’s opening chapter, entitled “Haiti’s Agonies and Exaltations.”

Ramsey Clark’s last delegation to Haiti was in October 2005, when the Haiti Commission of Inquiry visited Haiti for five days in concert with the International Tribunal on Haiti, which held hearings in 2005 and 2006 in Washington, DC, Boston, Miami, and Montreal. The tribunal was primarily investigating the war crimes of the United Nations occupation troops stationed in Haiti as the UN Mission to Stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH).

During its stay, the Commission met with eye-witnesses and the relatives of victims of UN and police massacres in Cité Soleil, Belair, Nazon, Solino, Carrefour, Canapé Vert, Pernal, and Belladères. Hours of testimony and evidence were videotaped, photographed, and recorded.

“It is absolutely imperative for the future of Haiti and to peace on earth that there be accountability for these crimes,” Ramsey said at the delegation’s Oct. 11, 2005 press conference at Port-au-Prince’s Holiday Inn. “If international forces under the auspices of the United Nations can come to Haiti and engage in systematic summary executions of its people, what place on earth will be safe from that power?”

A Man of Extraordinary Wisdom, Principle, and Eloquence

In May 2006, Ramsey Clark traveled to Montreal, Canada for the fourth International Tribunal on Haiti. At that hearing, he gave one of his most heartfelt and poetic tributes to the Haitian people. Here are extended excerpts.

“I’ve met with many heart-breaking stories from witnesses in Haiti – from Belair, Cité Soleil, outside of Port-au-Prince. Their faces are etched indelibly in my mind… We have to hope that that same spirit of Bolivar will provide protection to Haiti in a struggle which is more difficult than the struggle against Napoleon’s legions. Incredible that slaves without weapons could overpower the mightiest, and most effective and well-trained and well-directed armies of Europe and crush the legions of Napoleon. And today we see them facing the whole world that is dominated by wealth. This time, they’ve been up against the United Nations itself, acting subservient to the will, primarily, of the United States…

“The United Nations, which I staunchly support, needs the most radical types of reform if it is ever going to represent we the peoples of the nations of the earth as it purports to do, rather than two or three members of the Security Council, who are among the five permanent members who have a veto power over the rest of the world combined, individually…

“The Stephen Bikos of Haiti had to die because they were committed, they were courageous, they were intelligent, and they wouldn’t be stopped. We think they have failed. But we have to remember. We thought they had failed in 1990. We thought they’d failed in the second election of President Aristide. But unless there is accountability now, and unless we remove the same powers that assassinated Dessalines, and have twice removed President Aristide – and I mean the military, the paramilitaries, and the [death-squad] FRAPH, the Tonton Macoutes, all agents of the concentrated wealth of the island, of the multinational corporations which have interests there. We must prove there is no longer impunity for the actual agents of the power that intends to maintain the repression that has tormented what is to me the most authentic and the richest culture in the Western Hemisphere – perhaps because it has been so isolated – but nevertheless it shows the creativity, beauty, and potential of the human species.”

Remarkable in these words is not only Ramsey’s articulate passion, but that he was guided by principle. He cherished the UN as one of humanity’s great hopes at achieving world peace and prosperity, but he had begun to recognize that it was increasingly contributing to the opposite. In his final years, Ramsey did not flinch from holding the United Nations accountable for its crimes. His last speech in Haiti on Oct. 11, 2005 also reveals this and holds particular relevance for the current historical moment.

“I first came to Haiti in 1946, before probably anybody else in this room was born. Over the years, I’ve been back maybe a dozen times, but because of the nature of my work, never at a happy time.

“You have heard descriptions of terrible police and military violence against the people of Haiti. All who revere life and seek peace have to recognize that police and military violence against the people is the greatest of all crimes. Who will protect the people when the police and military are violating their rights?

“The very special context of this police and military violence against the people of Haiti has to be observed with the greatest care because it has happened in the wake of yet another U.S. regime change of the government of Haiti. Whatever might have happened if George Bush, and Dick Cheney and finally Colin Powell hadn’t said that Aristide has to go, we will never know. But what did happen because President Bush decided that Aristide has to go we know very well: systematic violence against the people of Haiti that is clearly, overwhelmingly politically motivated.

“You report in the press here regularly that there is a war against what they want to call gangs and bandits. What they are really talking about is Aristide supporters and the Lavalas. Very often they use the name Lavalas as a synonym for the gangs, the bandits. And they go out and commit summary executions against the people, to control the country for the future.

“We have to hope that that same spirit of Bolivar will provide protection to Haiti in a struggle which is more difficult than the struggle against Napoleon’s legions.”

“It is especially tragic to see the United Nations forces used in this way. The United Nations was created to end the scourge of war. Its first peace-keeping forces were unarmed. I remember the tragedy of seeing the bodies of six young men from Fiji wearing blue helmets and unarmed, killed by an Israeli invasion in southern Lebanon. Now what we see is MINUSTAH adopting the military tactics of Special Forces. We have to remember that soldiers come to love war too well. The United States has created an international militarism that mimics its tactics. You only have to look at Iraq today in towns like Falluja and elsewhere to see the systematic destruction of the resistance of the people…

“I served in the U.S. government for eight years in the 1960s. It was a period of civil rights. It began really for the government in 1961 with what we call the ‘Freedom Riders,’ with public school integration for the first time, so that African American and white children would go to the same school. The introduction of the first African American into the University of Mississippi in September 1962 cost several lives and thousands and thousands of rounds of ammunition fired to prevent the admission of one person into that university solely because of the color of his skin.

“For the next years, we addressed the problem of civil rights in the United States with the highest priority on the elimination of poverty. Gandhi correctly called poverty the greatest genocide. And in Malawi and Niger and other parts of Africa you see literally tens of millions of people at risk of starvation.

“But during the so-called War on Poverty in the United States, the expenditures for public education, for public healthcare, for social welfare, social security, housing and all the rest more than tripled. And then from rising expectations, beginning in August 1965, race riots broke out in our major cities. In Maryland in 1964, Los Angeles in 1965, Cleveland in 1966, Newark and Chicago in 1967. Then with the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. in April 1968, there were over 100 cities where race riots broke out spontaneously. Police repression was enormous. Hundreds of people were shot dead for the most serious offense of, perhaps, looting. People called for the shooting of looters. There was a picture of a 14-year-old kid who had been running down the street with a basket of apples, shot in the back and killed.

“The U.S. Department of Justice [which Ramsey Clark headed at that time] announced that its highest criminal law enforcement priority was the prosecution of police for violating the rights of citizens.

“And against the vehement opposition of the police and political power in the United States and the National Guard, we began to prosecute police in cities across the country who had killed citizens living in their own country.

“And that’s very much what’s happened here in Haiti. But you are afflicted not only with your own police, which have had their problems for generations, but with foreign military forces from many countries, acting under different commanders, under the auspices and direction of the United Nations, and they must be held accountable for their crimes.”

A Personal Note

I first saw and met Ramsey Clark in 1976 at a WESPAC meeting in White Plains, NY when he was running for New York’s Senate seat. Still a shy teenager, I was struck by his phenomenal oratory, his self-deprecating humility, and that he deigned to take time talking to me.

Although I met him again at numerous Haitian rallies in New York during the 1980s, it was on the December 1991 delegation to Haiti (where I acted as his top sergeant) that I began to truly get a sense of the man.

The delegation was fraught with logistical and security challenges, but Ramsey remained composed, focused, and courageous throughout.

There was a curfew in effect, and one evening, we had to return in our car two militants who had come to speak to our delegation at the Oloffson Hotel. It was too dangerous for them to walk home. Ramsey insisted on accompanying me on the drive up the hill to the Belair neighborhood where they lived, in case there was any trouble with authorities. As we drove up the hill, suddenly a car without headlights came hurtling down past us, followed by two men on a motorcycle shooting pistols at it. We were in the line of fire. I veered off to the side of the road and ducked my head under the dashboard. Ramsey, sitting in the passenger seat, never budged and remained completely calm.

On another night, some militants arrived very late, after Ramsey had retired, saying they could come at no other time. We sheepishly knocked on his door to ask if he would hear their story (about the Sept. 29, 1991 night massacre in front of the National Palace). Ramsey did not hesitate; he immediately dressed, and the meeting was held in his room.

(The Oloffson’s manager, Richard Morse, ended up naming a room after Ramsey Clark, No. 10 in the “maternity ward.”)

One of the people our delegation met with was the iconic protest singer Emmanuel “Manno” Charlemagne, who had taken refuge in the Argentinian Embassy in Pétionville. He sought safe passage out of the country with our delegation. When Ramsey broached the matter with the coup government, they insisted that $3,000 be paid before Manno would be allowed to leave. Ramsey gave Richard Morse his own personal check in return for $3,000 in cash. With the plane already on the runway, Ramsey and I traveled by taxi to a small government office in downtown Port-au-Prince, where the money was paid and a receipt procured. As often happens in Haiti, complications arose at the last minute, and Manno was unable to come to the airport to join the delegation for the flight back to the U.S.. Despite having several important obligations in his always packed schedule and the plane idling on the tarmac, Ramsey calmly deliberated for 10 minutes with delegation members about whether to stay behind to accompany Manno out. After several phone calls with Manno and others, he was satisfied that the singer could leave Haiti safely, which he did three weeks later.

Over the years, during delegation outings, Ramsey would often stand on the margins of a crowd which we were interviewing, looking off into the distance, a slight smile on his face. As I translated and took notes in the thick of it, I sometimes worried that he was not following what was being said. But then later, in meetings or press conferences, he would refer to details and statements that even I had forgotten, apparently summoned from his nearly photographic memory. Furthermore, he was able to summarize, in a few sentences, the essence of what dozens of interviews and experiences in a given day meant, and he knew how to fashion that testimony into a potent, memorable message, with historical and international context.

On the 1997 union delegation, he stood in the back of a flatbed truck with filmmaker Katharine “Keke” Kean outside Port-au-Prince’s SONAPI assembly industry park. “It never ceases to amaze me,” he remarked to her, watching the exhausted women workers stream out of the gates, “how much money there is to be made by exploiting the poorest of the poor.”

No matter how chaotic or dangerous events seemed to become, he always maintained an almost Zen-like composure. “Don’t worry too much about what you’re reading and hearing,” he once told me and a colleague with his laconic Texan drawl in his law office, as he prepared us for a particularly treacherous information-gathering mission during the first coup d’état. “Things always sound worse from a distance.”

He persevered through it all, despite great personal challenges and heartbreak, like the loss of his wife of 61 years, Georgia Welch Clark, in 2010 and of his son, Tom, 59, to cancer in 2013.

I, like so many journalists, activists, lawyers, and masses around the world, will miss his gentle serenity, profound morality, and great love for humanity that guided his heroic life, which, he once said, “is full of turbulence and conflict, and I never try to avoid either. In fact, I guess I seek them out because that’s where the chance to make a difference is.”

And make a difference, he did.