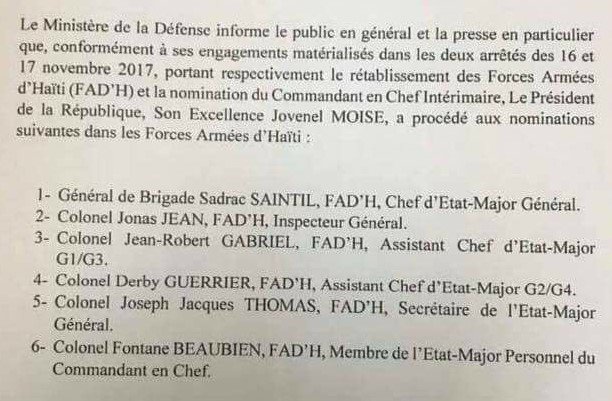

On Mar. 13, President Jovenel Moise appointed six individuals to the high command of the recently reinstated Haitian armed forces (FAdH). All of the appointees, now in their sixties, were majors or colonels in the former FAdH, disbanded in 1995 after a long history of involvement in coups, violent repression, and drug trafficking. At least three of the officers appear to have held senior positions within the early-‘90s military coup regime. One of them is a convicted intellectual author of a civilian massacre, and another was a member of a committee that sought to cover it up.

The makeup of the new leadership has raised concerns among human rights organizations over the trajectory of the new force and its commitment to the rule of law.

“The appointment confirms once again that the Haitian Armed Forces, remobilized by the [ruling Tét Kale party or PHTK] is a militia whose hidden mission is to have the Haitian people relive the darkest hours of bloodthirsty Duvalierism,” wrote the Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (BAI) in a press release, referencing the illegal arrests, forced disappearances, assassinations, and other abuses that characterized the Duvalier dictatorship.

Haitian Defense Minister Hervé Denis responded that the new high-command is “clean,” and that all were vetted for involvement in human rights abuses or drug trafficking.

In 1990, an outspoken liberation theologian priest, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, was elected in the first democratic election in the country’s history. But within months, a group of Haitian military officers – backed by many of the country’s wealthiest families – overthrew the new government, imposing a military dictatorship that would last three years. It was later revealed that the CIA had supported certain military elements involved in the coup, and that leaders of a paramilitary group that waged a campaign of terror against Aristide supporters and other activists were on the CIA payroll.

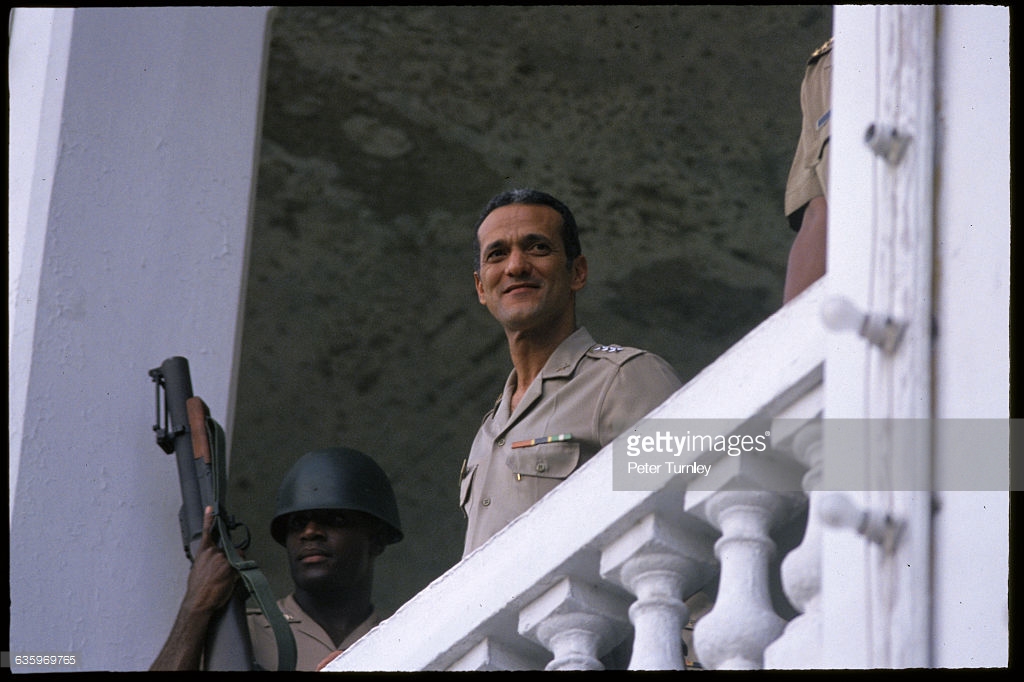

The group, FRAPH, helped to prop up the coup regime of Lieutenant General Raoul Cédras, while also at times appearing to undermine and sabotage the official actions of Clinton administration to restore democratic government to Haiti. Thousands of Haitians were murdered under the coup regime and hundreds of thousands fled the country.

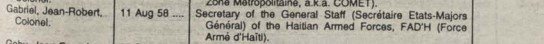

Colonel Jean-Robert Gabriel, the new FAdH’s assistant chief of staff, was the secretary of the general staff, and later a public spokesperson, for the Cédras regime.

Following the 1991 military coup, the U.S. and the international community implemented sanctions against the regime, eventually instituting an embargo. After Bill Clinton became president in January 1993, and increasingly in 1994, the Congressional Black Caucus played a leading role in pushing for a more aggressive role against the dictatorship, and solidarity groups in the U.S. and elsewhere also influenced policy.

In June 1993, the Clinton administration announced individual targeted sanctions against those determined to be a part of the “de facto regime in Haiti.” The initial sanction list, published in July 1993, named 83 individuals, including 29 military officers. Included in this initial list was Jean-Robert Gabriel.

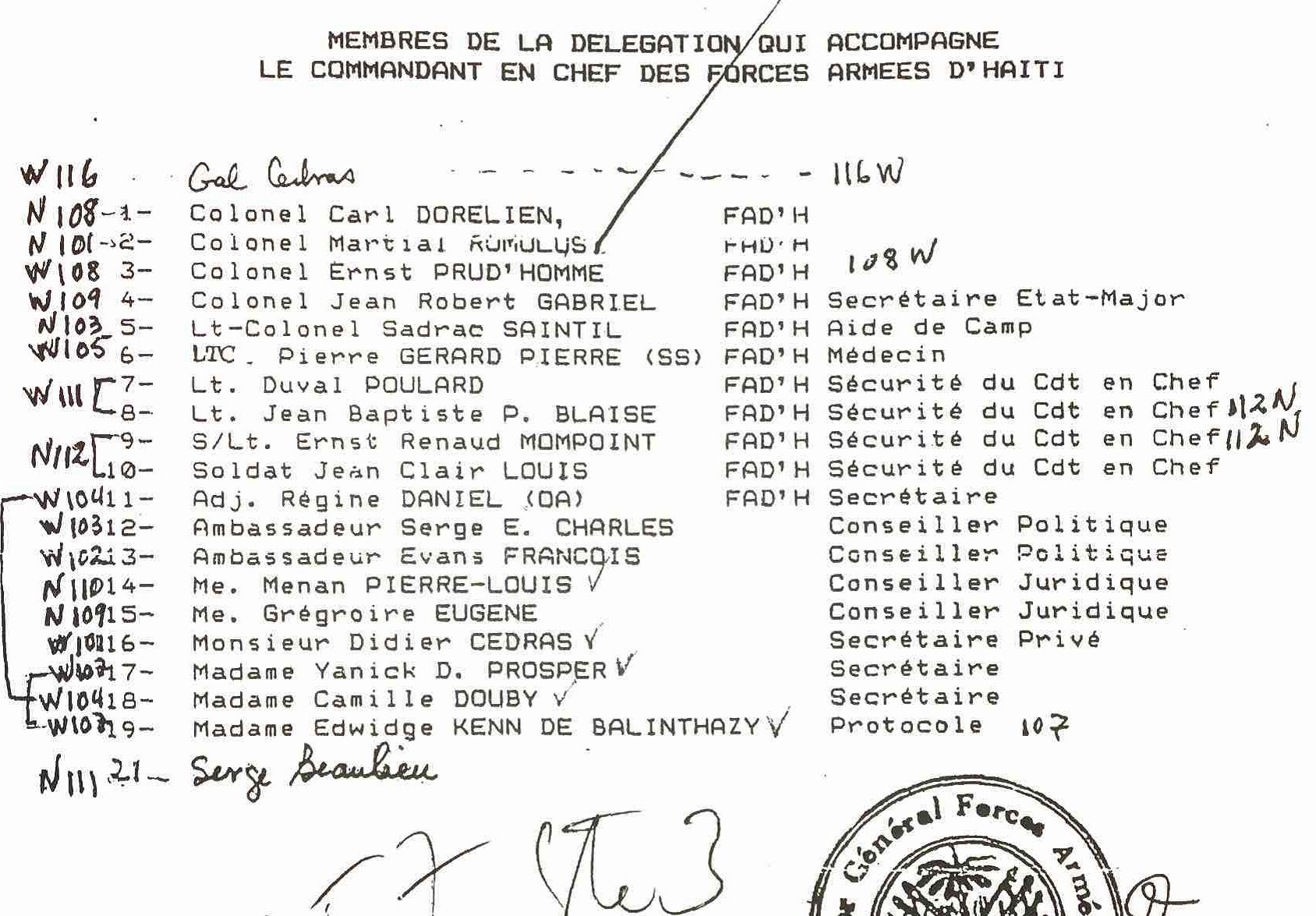

In 1993, the UN mediated indirect negotiations between Cédras and Aristide (who had taken up residence in Washington, DC to lobby for his restoration to office). Known as the Governors Island negotiations for the location where they took place, the eventual accord did little to immediately overturn the bloody coup. According to official documents, Gabriel, as well as the newly appointed chief of the general staff, Sadrac Saintil, were members of the delegation, indicating their senior positions within the Cédras regime.

The U.S. temporarily suspended some of the sanctions during the negotiations, but when it became clear that Cédras and his regime would not back down, the sanctions were expanded. In October 1993, the administration revoked U.S. visas and froze the U.S. assets of 41 officials who were determined to be thwarting a return to democratic rule and contributing to the violence in Haiti. Among the 41 individuals was Derby Guerrier, recently named as an assistant chief of staff in the reinstated armed forces ― and then a lieutenant colonel.

Guerrier held a U.S. passport, and a New Jersey address was listed next to his name. According to press reports at the time, Guerrier was the head of the military’s anti-drug unit. Though there is little public information about Guerrier, drug trafficking took off under the military regime.

A 1997 federal indictment in Miami alleged that Joseph-Michel François, a former military officer who helped topple Aristide in 1991 and later become the police chief under Cédras, “placed the political and military structure of the Republic of Haiti under his control” in order to facilitate drug shipments from Colombia. François, by that time, was living in exile in Honduras and managed to avoid accountability.

Back in 1994, with the situation in Haiti continuing to deteriorate, and more and more Haitians fleeing the country, the US expanded its sanctions policy. Some 550 military officers were added to the sanctions list, including all of those recently appointed to the FAdH’s new high command.

In April that year, around the same time the new sanctions were applied, Haitian military and paramilitary forces descended on the neighborhood of Raboteau, where many opposition supporters were apparently seeking refuge. At least eight, and likely far more, were assassinated.

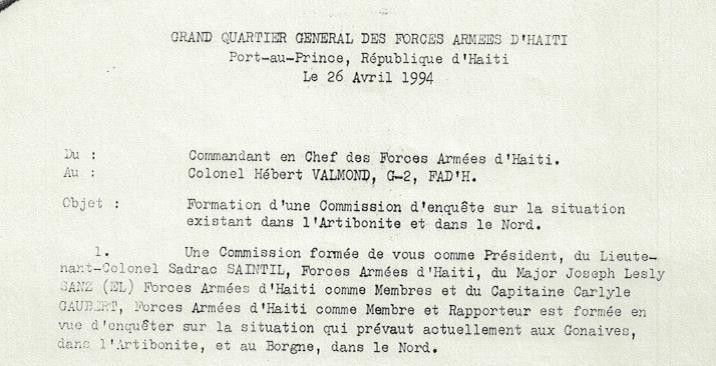

The next month a military-led commission of inquiry was tasked with investigating the allegations that a massacre had taken place in Raboteau. Cédras named Lieutenant Colonel Sadrac Saintil as one of four members, according to official documents made public as part of the Raboteau trial. Unsurprisingly, the commission found no evidence of a massacre and the FAdH high command accepted the commission’s recommendation that nobody be punished.

But in 2000, in a landmark human rights trial supported by the Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (the same organization now denouncing the new armed forces’ leadership), a Haitian court convicted 53 former officers and paramilitaries of involvement in the Raboteau massacre. Among the military officers convicted was Jean-Robert Gabriel. Though he was not implicated in direct involvement, he was charged under the theory of “command responsibility” due to his position within the top echelons of the Cédras regime.

“It’s the same type of case made against the Nazis and (Slobodan) Milosevic,” Brian Concannon, an American attorney who helped form the BAI in the early ‘90s and who worked the Raboteau case, told the St. Petersburg Times in 2002. Concannon is now the executive director of the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti (IJDH), a partner organization to the BAI.

The Haitian government has pushed back on Gabriel’s involvement in Raboteau. “What I can tell you in all honesty,” the Defense minister told the press, “the candidates were subjected to vetting, including Colonel Gabriel. There is nothing negative against him in the vetting with regard to human rights.”

In 2005, under a new de facto regime following Aristide’s second Washington-backed ouster (this one in 2004, and also backed by former military and paramilitary officers), the Haitian supreme court controversially vacated the sentences that had been handed down five years earlier. Most of those who had been convicted were on the run, including Jean-Robert Gabriel, who had taken up residence in Florida. Those that had been in jail escaped from prison years earlier.

After the convictions were overturned, Reed Brody of Human Rights Watch (who had previously worked with the BAI), commented: “In a country in which the poor have been killed and brutalized with impunity for centuries, Raboteau was perhaps the only time that justice was achieved after a massacre, and in a scrupulously fair trial … To overturn that verdict is to say that the only justice possible in Haiti is the justice of those with guns. It’s a sad day.”

By 2005 however, the Haitian Armed Forces had already been disbanded for 10 years.

On Nov. 18, 2017, 214th anniversary of the Battle of Vertières, the decisive battle in Haiti’s victorious fight for independence, current president Jovenel Moïse oversaw a military parade to celebrate the FAdH’s reestablishment. It was the culmination of a two-decade fight by former military officers and their civilian supporters that had received new life in 2010 with the election of Moïse’s predecessor, Michel “Sweet Micky” Martelly.

That’s the same nickname that François, the drug-trafficking former police chief, went by. He apparently got it from Martelly, then a popular musician, who has previously acknowledged his ties to François. During the Cédras regime, Martelly operated a nightclub that was frequented by his friends in the military.

While president, Martelly put the restoration of the military front and center in his party’s agenda. Martelly brought on the past dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier’s son as a counselor, and other officials with links to the Duvalier years populated the administration. “The army has always been a part of our policy…There is no way to have Haiti without an army,” a party representative told me in 2015.

On his way out of office, Martelly issued an executive decree reinstating the FAdH, but was unable to get it off the ground. That has changed under Moïse. Despite public opposition from the UN and the U.S. ― both of which have spent billions training the Haitian police ― Moïse has now fulfilled a major promise to a segment of the party’s supporters.

Moïse “vowed that the new military would be different” and would focus on protecting the country’s borders, responding to natural disasters, and civil engineering projects. But the appointment of six former FAdH officers to the new command ― all of whom are around the same age and were in same promotional class ― sends the wrong message, according to Concannon, the human rights lawyer.

“Filling the new High Command with people who played key leadership roles in Haiti’s de facto dictatorship demonstrates a determination to revive the brutal practices that caused so much suffering and undermined Haiti’s democracy and economy,” he said.

Rather than a modern force, the new military is starting to look a lot like the old one.

This article was originally published on the Haiti: Relief and Reconstruction Watch blog of the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR).