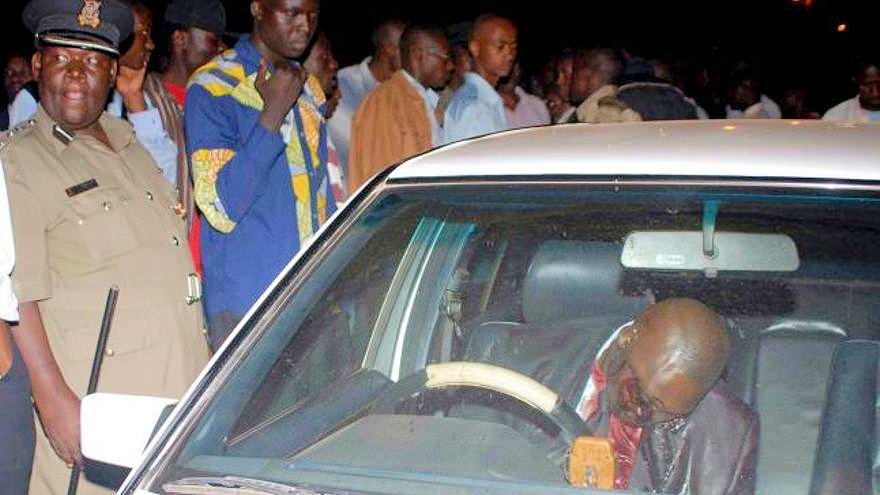

As Babu Owino landed at Nairobi’s Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, he called his wife to tell her he had arrived and would be home soon. However, the Kenyan parliamentarian that represents Embakasi East was soon handcuffed, blindfolded, thrown into a waiting vehicle, and taken to an unknown location by police. They held him incommunicado for three days, deprived of food and water, before presenting him to a judge after a habeas corpus application was made in court.

“I’m a messenger,” he declared. “You can kill the messenger, but you will never kill the message. If fighting for Kenyans will cost me my life, so be it. Since I was a student leader, I have been fighting for the interests of Kenyans, and I will continue fighting for them.”

Owino’s detention is just one example of the abuses Kenya’s police mete out, this one against an elected official no less.

But Owino was luckier than many Kenyans, walking away from the abduction with his life. Shadowy death squads with secretive ties to political figures have long operated within Kenya’s notoriously brutal police force and claimed thousands of victims.

Unless stopped by the Kenyan courts, parliament, or demonstrators, this terror will soon be exported to Haiti, where Nairobi will lead, with some 1,100 police special forces, a U.S.-organized invasion, which the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) blessed on Oct. 2, with Russia and China abstaining. The UN-deputized force, should it deploy, will be called the Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission.

UNSC Resolution 2699’s authors in Washington and Kenyan government officials have promised to avoid repeating the “mistakes” of the 2004-2017 MINUSTAH occupation, in which massacres were carried out against the civilian population and hundreds of children were raped by foreign soldiers with total impunity. But Kenya’s long history of operating death squads against its own population and partaking in ill-fated interventions abroad portend a humanitarian disaster for the Haitian people if they are soon under the Kenyan boot.

Police death squads terrorize Kenyans

“The Kenyan police are one of the most backwards,” explains Booker Ngesa Omole, a Communist Party of Kenya (CPK) militant. Kenyan cops have killed three CPK members this year, including one who Omole says was executed in his home in front of his parents. “They are a typical neo-colonial force.”

In 2008, the Kenyan human rights group Oscar Foundation published a report called Veil of Impunity which found that over 8,000 young people were reported to have disappeared or been executed since 2002. The report also described reports of “mass graves scattered all over the country… where most of the missing are believed to have been secretly buried after execution in cold blood.”

Much of this carnage was carried out by the “Kwekwe (Eagle) Squad,” which was formed in 2007 to battle the Mungiki, a secretive nationalist organization that modeled itself on the Mau Mau, who led an anti-colonial struggle in the 1950s.

“Mungiki emerged in response to historical injustices and inequalities in Kenya,” Omole said. “It gained significant popularity, especially in relation to land-related issues. However, this movement rapidly deteriorated when it was co-opted by the Kikuyu ruling elites for their political purposes.”

“The Kenyan police also leveraged the group’s existence to justify the extrajudicial killing of thousands of young, unemployed individuals on the mere suspicion of Mungiki membership,” Omole continued. “This period represented a grave example of mass extrajudicial executions.”

Disputes over the 2007 election erupted into violence, killing more than 1,000 and displacing 500,000, according to Human Rights Watch.

“This degenerated to a ‘police state’ with the formation of the infamous Kwekwe Squad,” the Oscar Foundation report states. “Following a series of beheadings, the government declared a shoot-to-kill order and ordered the police to conduct mass arrests of youths, some of whom were later found dead and dumped in Ngong forest.”

The Kwekwe Squad’s role was “to suppress the youth,” the Oscar Foundation continues, and it was “notorious for its acts of staged abductions and executions of innocent youths which occur with impunity.”

A separate 2008 report from the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, entitled The Cry of Blood, compiled at least 300 names of victims who had either been killed or disappeared, and 200 others who they were unable to identify.

When human rights groups began to conduct ballistics examinations on suspects who had been executed, the police changed their murder methods to include strangulation, drowning, mutilation, and bludgeoning, according to the report, accusing the police of crimes against humanity.

A 2009 report by the UN Special Rapporteur Philip Alston found that “death squads operating on the orders of senior police officials” killed 1,113 people following elections in December 2007.

The Oscar Foundation’s founder, Oscar Kamau Kingara, and fellow human rights investigator John Paul Oulo were assassinated, in 2009, reportedly by police, after providing information to Alston for his report.

The same year, police officer Bernard Kiriinya was murdered after recording video testimony saying that he witnessed the Kwekwe Squad strangle and hack to death 58 people. Others were poisoned to avoid ballistic investigations by human rights organizations. The bodies, he said, were left in a national park, to be eaten by hyenas, and in a sewage plant.

“All the non-commissioned officers in our squad were given 15,000 shillings ($190) each and the constables were given 10,000 shillings each as a sign of appreciation for ‘kazi mzuri’,” Kiriinya said, using the Swahili term for “’good work.”

In 2020, Wikiealks published a letter from a Kenyan policeman alleging that former First Lady Lucy Kibaki and retired Police Commissioner Major General Mohammed Hussein Ali ordered the Kwekwe Squad to murder several prominent politicians. It also killed “1,869 Mungiki, and 631 suspected robbers.” At least a dozen of the officers who carried out the killings died or disappeared, the letter said.

A 2021 Nation report called the Kwekwe Squad a “well-structured execution squad within the National Police Service (NPS) charged with the elimination of crime suspects.”

Following the 2007 election violence, Kenya formed the Waki Commission to reform the police. In March 2009, police announced that the fearsome Kwekwe Squad was formally disbanded, and in May, President Mwai Kibaki created the National Task Force on Police Reform. The following year, Kenya passed a new constitution, promising accountability and reform.

However, little changed. A 2016 report found that Kenyan police shot dead more than 1,200 people in the previous five years.

Even the U.S. State Department’s Kenya 2018 Rights Report noted “unlawful and politically motivated killings; forced disappearances; torture; harsh and life-threatening prison condition” among other crimes, and accused the government of paying lip service to reforms. “Impunity at all levels of government continued to be a serious problem, despite public statements by the president and deputy president.”

In 2019, the Director of Criminal Investigations met with families of the victims and promised to investigate the death squads.Though he disbanded the police’s “Flying Squad,” the killer cops were merely reshuffled to other police units. “Sting Squad Headquarters” and another death squad called the “Directorate of Criminal Investigations Special Service Unit” (SSU) replaced it.

From SSU’s inception in 2019 until September 2022, Amnesty International Kenya documented 559 cases of extra-judicial killings and 53 cases of enforced disappearances, linking the squad to most of the cases.

In October 2022, the charade was repeated. The SSU was disbanded, with President William Ruto stating that “the police changed and became killers instead of protectors of ordinary Kenyans.” As before, the killer cops were not charged but once again reshuffled and assigned to different units.

Amnesty International Kenya was skeptical of Ruto’s announcement, stating that “many other ‘special units’ accused of serious violations, such as the Flying Squad and Kwekwe Squad, have previously been disbanded without necessarily ending the violations.” AI called on him to “extend this action across all security and policing agencies, including the Kenya Forest Service, Kenya Wildlife Service, the Kenya Defence Forces, and the Anti-Terrorism Police Unit.”

In July 2019, HRW submitted a report to the UN Human Rights Council stating that Kenyan police and pro-government militias killed 100 people during election protests and that police extrajudicially executed 21 men and boys in Nairobi’s poor neighborhoods. HRW published an accompanying statement saying that Kenya failed to meet its promises to the UN.

U.S. maintains strong support for Kenya

Despite this dismal human rights record, Washington heavily funds and trains the Kenyan police, dating back decades.

This support was surely increased in the Sep. 25 security deal with Kenya, which U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin flew to Nairobi to sign, although details of the accord have not been made public yet.

In sync with U.S. designs, Kenyan military forces have long participated in military interventions abroad, from Yugoslavia to Somalia.

Kenyan Deputy Inspector General Police Administration Service Noor Gabow, who was shepherded around Port-au-Prince by State Department personnel and U.S. military forces during an August reconnaissance mission, is a graduate of the British government’s police training program. He spent five years in UN Missions in Sierra Leone and Bosnia where Kenyan forces stole and sold $100,000 worth of fuel, and frequented a brothel, according to the Washington Post.

Gabow is also Acting Mission Management Coordinator at the UN Police Division. He currently leads a paramilitary wing of the Kenyan National Police Service.

It’s no coincidence that Kenya’s police force is not only the most brutal on the African continent, but also the largest recipient of U.S. support.

“Kenya is routinely among the largest recipients of U.S. foreign aid and is a top recipient of U.S. security assistance in Africa,” a 2020 Congressional Research Service document states. “Alongside State Department-managed military aid, the Department of Defense has provided over $400 million in [counter terrorism] ‘train and equip’ support to Kenya in the past decade.”

A Wall Street Journal article described the U.S. embassy’s influence over police and security forces in Kenya. “We, for the most part, have operational control,” said Supervisory Special Agent Ryan Williams of the State Department Bureau of Diplomatic Security.

This control is maintained through a reward system, which is highly lucrative for Kenyan police.

“Kenyan officers who win positions in vetted units get upgraded training, the prestige of working in an elite squad and, depending on the unit, as much as twice their usual pay. U.S. agencies provide intelligence they might not share with ordinary Kenyan police,” the WSJ article explains.

“The benefits of such collaborations and partnerships are immense” commented Inspector Mike Mugo, a spokesman for the Kenyan Directorate of Criminal Investigations.

In February 2020, the FBI and the Department of State trained 42 Kenyan police and intelligence officers.

When dusk-to-dawn curfews were imposed under the pretext of combatting COVID-19, zealous cops in riot gear tear-gassed and brutalized laborers awaiting a ferry to return home after work, two hours before the evening curfew started. Slums and informal markets under lockdown received similar abuses as workers begged for mercy.

Those caught violating the curfews were subject to brutality, no matter the reason. Police beat to death motorcycle taxi driver Hamisi Juma Mbega, who was taking a pregnant woman to the hospital after curfew. They killed three other motorcycle taxi drivers who were protesting the arrest of a colleague for not wearing a mask.

Thirteen-year-old Yasin Hussein Moyo was standing on his home balcony when he was shot dead by police on an after-curfew patrol. While police insisted Moyo was not targeted and was hit by a stray bullet, they killed at least 24 anti-lockdown protesters providing no such justification.

Two brothers, 22-year-old Benson Njiru Ndwiga and 19-year-old Emmanuel Mutura Ndigwa, disappeared in police custody during curfew and were found two days later in a morgue.

In total, 167 people were killed or disappeared in 2020, according to the Missing Voices annual report.

In total, 167 people were killed or disappeared in 2020, according to the Missing Voices annual report.

In the lead up to the MSS, the trend of unrelenting Kenyan police crime has not changed.

In October 2022, video emerged of police executing two suspected criminals after forcing them to lie down on the ground.

This year – in a strikingly similar scenario to last year’s uprising in Haiti – massive protests against election irregularities and fuel price hikes, imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), erupted under the banner #Maandamano against President William Ruto. The cost of living has compelled at least one man to self-immolate in protest.

Kenyan police killed 35 protesters in July alone, according to the AP, compelling The UN Human Rights Office to issue a statement that it is “very concerned by the widespread violence, and allegations of unnecessary or disproportionate use of force, including the use of firearms, by police during protests in Kenya.”

According to the Kenyan NGO Missing Voices, in 2022, police killed 130 and disappeared 22 people, and in 2021 they killed 187 and disappeared 32.

Despite Human Rights Watch’s documentation of Kenyan forces terrorizing their own population, it blessed plans for the invasion of Haiti.

U.S. hides behind Kenyans

Washington has been careful to de-emphasize its role and couch the intervention as a multinational effort to assist the beleaguered Haitian National Police (PNH), but the mission is essentially a U.S. military operation. As I revealed for Redacted, U.S. Army Special Forces were deployed to Haiti nearly two months ago in a “train-and-equip” mission. U.S. soldiers will likely accompany the PNH units they train and thus see action.

The U.S.-trained forces will be complemented by personnel from more than a dozen other countries, including Spain, Jamaica, Barbados, Mongolia, Senegal, Guatemala, Peru, Italy, Antigua and Barbuda, Surinam, and the Bahamas. However, Kenya has pledged to provide 1,100 police officers, the bulk of the manpower. Kenyan parliamentarian Nelson Koech boasted that Kenya’s contribution will be highly-trained special forces, not traffic cops.

Washington has sought to highlight Kenya’s contribution, with its diplomats even branding the deployment as a gesture of Black solidarity. (Kenya’s President William Ruto and his then Foreign Minister Alfred Mutua said the deployment was motivated by “Pan-Africanism.”)

The Pentagon has been planning a variety of military operations for various scenarios since President Jovenel Moíse’s assassination on Jul. 7, 2021. As part of the proxy doctrine described by Antony Blinken as the Biden administration prepared to take office, it avoids direct military interventions and prefers to use secretive military operations and proxy forces.

The Biden administration sought to enlist Kenya only after Jamaica and Canada both declined to lead the mission, and Brazil agreed only to contribute financial support. According to a source close to the PNH, Nairobi was bribed with $50 million to provide personnel.

“Replacing local gangs with a foreign gang”

Matthew Hoh, a former U.S. Marine who worked in the Pentagon and State Department from 2002 to 2008, described the proposal of a UN-sanctioned Kenyan mission as based on the fallacy of counterinsurgency doctrine, which he witnessed during deployments to Afghanistan.

Local groups, even those engaged in criminal activity, he says, “have a constituency that a foreign force does not bring. So you’re basically going to be running into this problem of replacing local gangs with a foreign gang and expecting that the population is going to ally themselves with foreigners.”

Kenya’s long history of operating death squads against its own population portends a humanitarian disaster for the Haitian people

This doctrine has repeatedly failed to achieve its stated intentions.

“Overwhelmingly, and particularly since World War II, we’ve seen that it has not worked and will make a situation that is already bad for the people of Haiti even worse,” Hoh says.

Even if the UN-sanctioned force does manage to beat back the Haitian groups, Hoh warns that they would likely splinter into a patchwork of smaller armed groups that battle each other for territory, citing experiences in Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria.

“A foreign force that comes in functioning as light infantry to engage in gun battles with these gangs is going to be very nasty and very bloody,” he says. “That can lead to fragmentation and a devolving situation.”

Even if the Kenyan force is able to defeat the armed groups, he says, civilians will pay the price.

“That bloodletting is going to have a massive effect on the people, because we know that in this type of warfare, civilians are the casualties,” Hoh concluded.

Haitian cops also have death squads

The Kenyan death squads will just add to those already existing in Haiti.

Beyond the problems with counterinsurgency strategy, corruption runs rampant to the highest levels of authority. Vitel’homme Innocent, one of the most dangerous criminals in Haiti who has emerged over the last year as leader of the Kraze Barye (Break down the wall) gang, has publicly stated that he was formerly tied to André Michel, a key ally of de facto prime minister Ariel Henry. Michel has denied the connection, but a source that worked for months in Haiti’s Interior Ministry says Vitel’homme remains close to him and Henry.

As Haiti Liberté journalist Kim Ives and I documented in the series Another Vision: Inside Haiti’s Uprising, a policeman named Vierry murdered and dismembered Jameson Verly, then proceeded to play soccer with his head, simply for being from the neighborhood of Delmas 6. Verly’s sister, Guerdy Verly, commented that he was killed in order to “make Barbecue cry” – using the nickname of Jimmy Cherizier, the leader of the anti-crime federation the “FRG9 Family and Allies.”

Policemen and an affiliated gang from Belair also kidnapped, doused with gasoline, and set ablaze Lorbeca Brutus, a Delmas 6 resident, who told her rescuers that she too was targeted because she was from Cherizier’s neighborhood.

Despite their brutality, the Kenyans will likely not succeed

Corruption aside, Brookings Institute fellow Vanda Felbab-Brown publicly doubts that the MSS would have any efficacy, noting that half of the force of 1,000 Kenyan police would be devoted to protecting and securing installations and personnel, leaving a 2:1 or 1:1 gang/police balance.

She said that this comparatively small Kenyan force would be further disadvantaged inside Haiti’s sprawling slums, describing them as “ the most complex urban terrain environment we can imagine.”

Beyond that, the multinational force will have little understanding of Haiti’s geography, human terrain, intelligence, and will be hampered by an inability to replenish depleted forces over time, she said.

Furthermore, she noted that neither the Kenyans nor their backers have presented an exit strategy, and that whatever gains may be made, the PNH is incapable of maintaining control after a Kenyan departure.

“How can this intervention go right?” she concluded on Twitter.

Whatever the case, the MSS will surely increase in size and time deployed. “A recent assessment by Kenyan officials estimated that the project would take three years and require from 10,000 to 20,000 personnel, Mr. [Alfred] Mutua said,” reported the Oct. 4 New York Times citing Kenya’s recently demoted Foreign Minister.

Washington’s 10 year plan for Haiti

Despite the MSS’s unfavorable odds for success, its primary purpose appears to be to set the stage for a long-term U.S. military occupation. Haiti, an historically vanguard nation and target of the U.S. empire, is the test case for a recent piece of legislation called the Global Fragility Act, which is set to become U.S. imperialism’s worldwide strategy. The GFA requires Washington to design plans that last 10 years.

the imminent foreign intervention will achieve, at best, a stalemate which fails to dislodge the gangs and achieve its stated goals, or, at worst, a blood-soaked misadventure that would brutalize Haiti’s civilian population.

A State Department strategy document explains “The GFA calls for the United States Government to create a unified United States strategy that is intentional, cross-cutting, and measurable, and harnesses the full spectrum of United States diplomacy, assistance, and engagement over a 10-year horizon to help countries move from fragility to stability and from conflict to peace.” It adds that “In certain settings, the United States military can play a critical role in facilitating basic public order, responding to immediate needs of the population, and building the capacity of foreign security forces,” and that “The United States military will enhance its ability to support this Strategy through small-footprint, coordinated, partner-focused activities in line with DoD Policy Directive 3000.05 “Stabilization” and United States national security objectives.”

At the very least, in the words of the Council on Foreign Relations, U.S. imperialism’s preeminent think-tank, “Haiti needs to become a ward of the United Nations, a revived ‘trust territory.’”

With the vague, open-ended nature of the mission, and the incredible challenges of a foreign force waging counterinsurgency inside complex urban terrain, it is clear that the imminent foreign intervention is Haiti will achieve, at best, a stalemate which fails to dislodge the gangs and achieve its stated goals, or, at worst, a blood-soaked misadventure that would brutalize Haiti’s civilian population. Either way, military intervention will only reinforce the deeper social, political and economic crises birthed by decades of U.S. imperialism and which gave rise to the gang phenomenon in the first place and may provide the justification, however lame, for the long-term military occupation that the U.S. seeks.

This article was first published on Dan Cohen’s website Uncaptured.substack.com.

[…] were to happen, it would be a huge setback for Washington’s plans in Africa. Last Sep. 25, U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin was in Nairobi to ink a still shrouded security deal with Kenya, making it a key U.S. chess piece in East Africa. […]

[…] this were to happen, it would be a huge setback for Washington’s plans in Africa. Last Sep. 25, U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin was in Nairobi to ink a still shrouded security deal with Kenya, making it a key U.S. chess piece in East Africa. […]