The last of three installments (Second part)

Chapter Three: Financial Occupations

The reaction to the [U.S. Marines’] removal of the gold [from the vaults of the Banque nationale de la République d’Haïti] was as [Arthur] Bailly-Blanchard [the U.S. Minister to Port-au-Prince] predicted. The news quickly spread throughout Port-au-Prince and was greeted with shock and disbelief. Editorials in Le Nouvelliste and Le Matin immediately speculated over the nature of the incident and its infringement of the sovereignty of the Haitian nation. The Haitian government sent commissioners to the bank to ascertain whether the bank funds were still available. The clerks of the BNRH refused to open the vaults, as ordered by their superiors in New York. [BNRH manager Henri] Desrue was accused of embezzlement and threatened with imprisonment. He wrote a desperate letter to [Henry H.] Wehrhane [of Hallgarten & Co.] asking for protection, while the State Department instructed Bailly-Blanchard to request protection from the Haitian government for the BNRH’s employees. The government then began legal proceedings against the bank, initiating a back-and-forth that would continue over the next few months as government officials attempted to both verify the amount remaining in the BNRH’s vaults and appropriate portions of it to maintain the functioning of the state. Ministers were called before the Haitian Chamber of Deputies to explain the situation while Solon Ménos, the minister of foreign affairs, sent a formal protest to the U.S. State Department.

In his protest, Ménos pointed out that the fund was property of the Haitian state, not the bank, and could not leave the treasury without consent of the government. Ménos argued that the “good faith of the Department of State has been abused,” and he sought an explanation. He… requested that the State Department “disown” the actions of the bank and order restitution to the Haitian government.

[U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings] Bryan’s response to Ménos was condescending and dismissive. He asserted the BNRH was a private bank, and the gold in question belonged to it with the specific purpose of retiring the paper currency under the 1910 loan agreement. He also claimed that various revolutionary governments had tried to seize the gold for their own purposes, making its status “precarious” and prompting the directors to remove it to a place where it was not only safe, but might draw interest “pending the retirement of the Haitian currency.” He further claimed that the [USS] Machias was deployed only because no other means of transportation was available and that armed U.S. Marines were landed because “American interests” were “gravely menaced.” (…)

Ménos was baffled. He was “surprised and pained” that the United States would interfere in Haiti’s internal affairs, and pointed out that the BNRH was a French corporation headquartered in Paris, charged with the treasury service of the Haitian state, and bequeathed the rights of Haitian citizenship. Based on these facts, the United States had no right to intervene. (…)

“The time to act is now,” U.S. president Woodrow Wilson wrote to Bryan on Apr. 5, 1915. Days before, Bryan had conferred with [U.S. diplomat] Robert Lansing on the “Haitien [sic] situation” and then solicited the president’s opinion. For Bryan, the situation had become an “embarrassment.” He felt that Bailly-Blanchard was not doing his job, and that the current Haitian president seemed amenable to signing a convention with the United States, whose terms included the U.S. control of Môle-Saint-Nicolas. Furthermore, he was frustrated with the state of the BNRH. The French still controlled 50% of its stock, while the rest was split evenly between U.S. and German interests. While the U.S. bankers wanted to remain in Haiti, they wanted to do so on condition of not only the protection of their interests in the bank and their other investments, but the control of Haiti’s customs receivership. Bryan… believed the United States should be assertive in its Haiti policy, assuming control of both the long-desired Môle-Saint-Nicolas and the finances of the country. Bryan quickly summoned Wehrhane and Farnham to Washington to discuss the matter and the possibilities of the “Americanization” of the BNRH, and, as Farnham later put it, “[the elimination], as far as possible, [of] European influences in the island.” (…)

Events in Port-au-Prince expedited the State Department’s goals for Haiti and for control of the BNRH. The night of Jul. 27, 1915, the BNRH’s William H. Williams was startled from his sleep at the Hotel Montaigne. Williams quickly dressed and, joined by the newly appointed American chargé d’affaires, Robert Beale Davis, Jr., went downtown in the direction of the bank as the sound of musket fire and machine guns echoed off the buildings. As dawn broke over the city, they learned that Haitian president Guillame Sam, whom the United States thought would be amenable to an agreement, had arrested and imprisoned 175 of his political opponents. As talk of a revolt against Sam grew, he ordered the massacre of the prisoners. Crowds filled the streets of Port-au-Prince and descended on the prison to account for their relatives. Fearing his life, Sam sought refuge in the French legation, only for his opponents to drag him into the street, killing him. Amid the upheaval, Davis made his way to the U.S. legation, telegraphed William Caperton, captain of the USS Washington, stationed at Cap-Haïtien. The Washington quickly sailed to Port-au-Prince, where Caperton disembarked [on Jul. 28] with 500 men, placing soldiers at the BNRH and other locations. The U.S. military occupation of Haiti had begun.

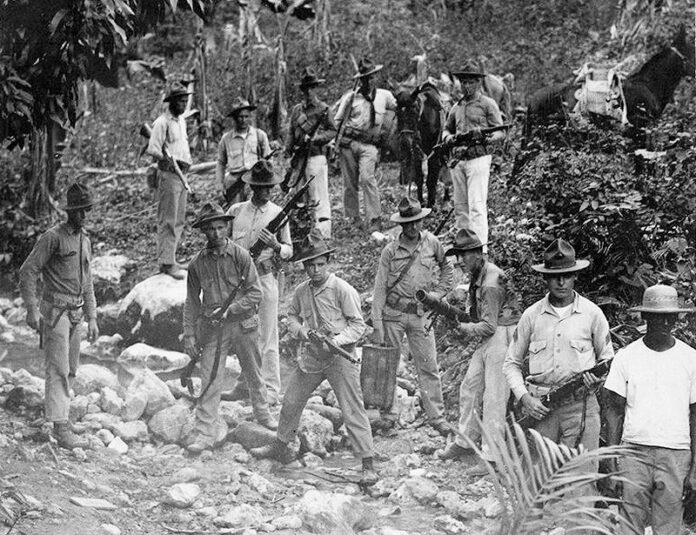

The U.S. occupation of Haiti was brutal in its administration. Haiti’s political classes were muzzled, and its assembly was deprived of power. Elections were staged, and a puppet president in the figure of Louis Borno, was installed. Martial law reigned, and the press was censored. For the Haitian elite, the experience was a humiliating one. Not only were they unceremoniously dethroned from their positions of political power, but the codes and cultures of white U.S. racism demoted them to the status of the black peasant. While at the beginning of the occupation there was a brief insurgency led by peasant insurrectionists, known as Cacos, lasting from July to November 1915, it was quickly crushed. To neutralize the potential threat of future insurrections, U.S. Marines methodically fanned into the countryside destroying villages in a slash-and-burn campaign and arresting or assassinating suspected Cacos.

A police state overseen by U.S. Marines was established; rule of law was enforced by a militia force, the Garde d’Haïti, whose lower officers were recruited from the Haitian populace. In 1917, work began on a 170-mile highway connecting Port-au-Prince via Bathon, Gonaïves, Ennery, and Saint-Marc to Cap-Haïtien, and then from Port-au-Prince toward the Dominican border to Hinche. This road-building project had two aims. It was initiated as an attempt to develop a communication and transportation infrastructure that would link the outlying regions of the country to the coastal cities and, following this, open up the country’s potential wealth in coal, sugarcane, bananas, and cotton to international markets. The United States also saw the road project as a means of promoting stability and maintaining military control through the surveillance and containment of the Cacos. U.S. officials recognized the isolated regions of the country, especially near the Dominican border, were a major contributor to the historical problem of insurrection. They correctly linked the geographic diffusion of the Maroons of the revolutionary era to the spread of the Caco revolts of the early 20th century.

Through the activation of the 1864 Haitian corvée law the U.S. Marines found the necessary labor for the road project. According to the corvée, peasants were required to work on local roads in lieu of paying road taxes. (“They had the option,” quipped General Smedley D. Butler, the U.S. Marine in command of the project, but “nobody had any money, so they reported for work.”) Those who refused to work or who tried to escape were tortured, jailed, or executed.

For many Haitians, the corvée appeared to be “a return to racial slavery,” while for the U.S. Marines, it was an extension of the chain gangs of the U.S. South. It sparked another revolt against the United States, led by Charlemagne Péralte, a former schoolteacher who had been conscripted into the road-building project. After his escape from the chain gang, Péralte set up a provisional government in Hinche and planned to seize the town of Grande Riviere. Péralte was betrayed by a Haitian within his camp and assassinated by U.S. Marines the night of Oct. 31, 1919. After Péralte’s death, Benoît Batraville took up the leadership of the rebellion and tried to seize the capital. Several hundred Cacos were slaughtered in the attempt, and Batraville, too, was betrayed. He was killed on May 20, 1920. “His death, it is believed, assures complete pacification,” a U.S. Navy report concluded. In all, some 3,000 Haitians were killed in the first five years of occupation as hunting Cacos and torturing peasants became a “sport” for the Marines. (…)

Indeed, for the City Bank, the U.S. occupation of Haiti was good business. While Haiti’s sovereignty was extinguished, the treaty forced on Haiti by the occupation authorities meant the regularization of customs collections — and hence regularization of interest payments on both the PCS Railroad and the floating debt — by a U.S.-nominated, Haitian-appointed receiver. John H. Allen believed that if the occupation was to become permanent, the City Bank should acquire the entire stock of the BNRH. He saw the rich possibility of the BNRH, arguing that if it were properly managed, it would “pay 20% or better.” Allen used the opportunity of the occupation to extend the City Bank’s control of Haitian commerce. He pushed the U.S. financial adviser to rewrite the BNRH’s contract to include a clause giving the bank a monopoly on the import and export of currency. (…)

Haiti’s political classes were muzzled, and its assembly was deprived of power.

The following spring, articles in the City Bank’s The Americas lauded the new regime and the new era in Haiti. At the same time the City Bank bought out the remaining German interests in the BNRH after they were seized by the French government. The bank used its stock-holding affiliate, the National City Company, as the vehicle for the purchase. The following year, the City Bank purchased the shares of Hallgarten, Speyer, and Ladenburg Thalmann. While the French remained the majority stockholders in the bank, control of its everyday operations was slowly shifting to the United States.

During the first five years of the U.S. occupation of Haiti, the City Bank was seen in the United States as an important presence, stabilizing and rehabilitating the finances of a backward, chronically revolutionary country that was ill prepared for self-government. But in 1920 perceptions of the occupation began to change. That fall, The Nation published a four-part series titled “Self-Determining Haiti,” written by James Weldon Johnson, the field secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People [NAACP]. Johnson had traveled to Haiti in the spring to investigate the conditions of the occupation. His assessment was searing. His articles presented a damning history of the occupation that placed the City Bank at its center.

“To know the reasons for the present political situation in Haiti,” Johnson wrote in the introduction to the series, “to understand why the United States landed and has for five years maintained military forces in that country, why some 3,000 Haitian men, women, and children have been shot down by American rifles and machine guns, it is necessary, among other things, to know that the National City Bank of New York is very much interested in Haiti. It is necessary to know that the National City Bank controls the National Bank of Haiti and is the depository for all of the Haitian national funds that are being collected by American officials, and that Mr. R. L. Farnham, vice-president of the National City Bank, is virtually the representative of the State Department in matters relating to the island republic.”

The occupation, Johnson asserted, was “of, by, and for the National City Bank of New York.” He argued that the City Bank exercised a force in Haiti that, “because of its deep and varied radications,” was “more powerful though less obvious, and more sinister,” than the State Department or the U.S. Marines. The City Bank, he claimed, was “constantly working to bring about a condition more suitable and profitable for itself” through its attempts to install a financial adviser and a receiver general who dictated how government revenue was collected and disbursed, by monopolizing access to credit and the importation of specie, by pushing a $30 million loan on the country, and by consolidating control of the BNRH. The City Bank, according to Johnson, tried to effect “a strangle hold on the financial life” of Haiti.

Behind this control, and, ultimately, behind the U.S. occupation, was the figure of Roger Farnham. As the point person for both the bank and the State Department in Haitian affairs, Farnham “was effectively instrumental in bringing about American intervention.” Johnson’s articles, along with others, shocked the U.S. public, a majority of whom had believed in the benevolence of the occupation, and prompted a number of investigations. An internal investigation by the U.S. Marine Corps responded to allegations of Marine atrocities by concluding that the Marines had acted in a moral manner and that their presence was entirely beneficial to the Haitian people. A congressional investigation was launched the following year, and its conclusions were much the same. (…)

Johnson’s efforts spurred the organization of Union Patriotique d’HaIti, a nationalist organization made up of Haiti’s elites, who, through the 1920s, protested the occupation through the press and diplomatic means. (…)

On Aug. 17, 1922, the BNRH had begun operating under a new charter, and its management and supervision were moved from Paris to 55 Wall Street. The City Bank’s acquisition and control of the BNRH was complete… The control of the BNRH and the finances of Haiti represented the fulfillment of the vision that Frank A. Vanderlip and the City Bank had had for Haiti as early as 1909, and signified a managerial triumph in attempts at diversifying and expanding the bank’s operations. For Haiti, such control represented the end of independence and, as the BNRH and the republic’s gold reserve became mere entries on the ledgers of the City Bank, a sign of a return to colonial servitude.

Peter James Hudson is assistant professor of history and African American studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. His book “Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean” is available from the University of Chicago Press.