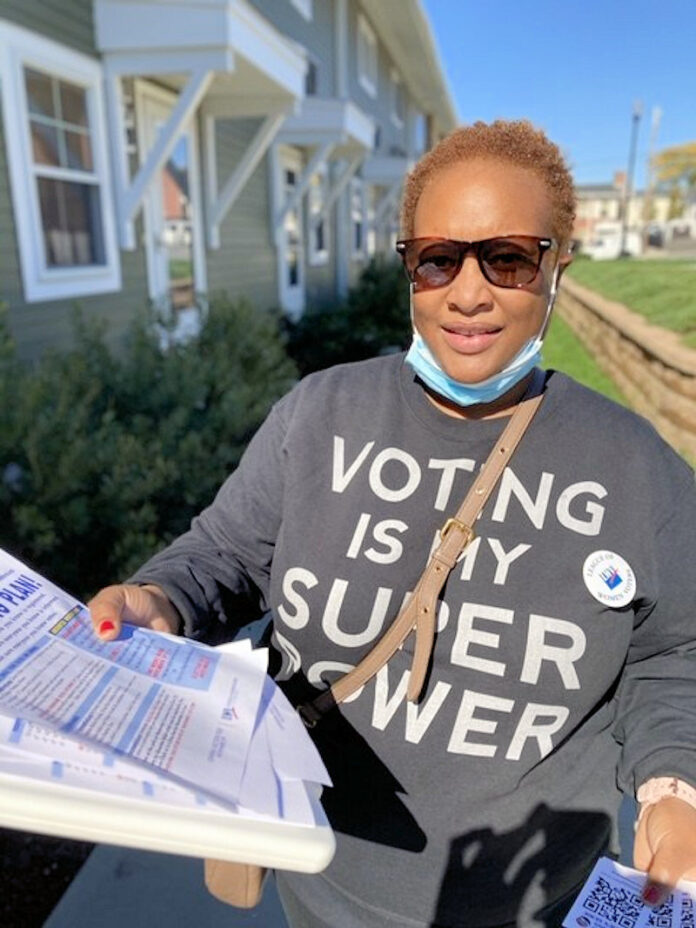

As the Nov. 3 election day fast approaches, Connecticut resident Bianca Shinn-Desras is doing everything she can to galvanize her state’s Haitian-American community. Taking a boots-on-the-ground approach, Shinn-Desras and other volunteers are knocking on doors in the state’s small Haitian enclaves to provide information on how to vote, combating misinformation on Facebook and WhatsApp, and working with pastors to deliver useful updates to their congregations.

“Connecticut is one of 10 states in the U.S. that has a large Haitian population,” said Shinn-Desras, who lives in Stamford. “It’s often neglected because it’s not Florida or New York, but it is in that corridor — between New York, Massachusetts and the Northeast — and that’s powerful.”

Connecticut’s dynamic Haitian-American residents are intensely involved in turning out the vote in their communities.

At an estimated 20,000, Haitian-Americans in the Constitution State are few compared to New York and Florida, where they are a visible voting bloc. Nonetheless, Connecticut’s dynamic Haitian-American residents are intensely involved in turning out the vote in their communities.

Without accurate, easily accessible data to support their participation, however, numerous advocates and academics have said, the community will miss out on resources it is due. Census data, they say, doesn’t reflect the true larger numbers of Haitians.

The lack of data has left many, like Shinn-Desras, who is an associate data strategist for a non-profit, calling for a deeper level of detail about voters.

“This is inequity in data collection,” said Shinn-Desras, 39. “You have a population that you’re not gaining information about, not providing open data, and it’s a problematic practice.”

Feeling invisible

Statistics from election boards in nine states with large Haitian populations, as well as official numbers by the U.S. Census Bureau, do not reflect the visible political participation of Haitian-American communities across the country. The majority of local and statewide election boards only record voter statistics by race, not by ancestry or ethnicity.

In politically active Connecticut, the state only provides a voter’s gender.

The absence of data on Haitian-American voters feels as though Connecticut is treating them like a forgotten population, Shinn-Desras said. Were these statistics to become available, she would use them in promoting political discourse and engagement throughout her community.

“In the future, we definitely have to be able to capture the data because, while we are Black Americans, our ethnicity is still very important,” Shinn-Desras said. “We need to be able to capture that, and I think by not having that, we’re losing momentum.”

Others say different generations participate in politics in their own way, making the need for data a necessity to guide effective voter outreach toward each group. The methods used across generations, for one, could be adjusted with the appropriate data to support outreach.

“There is the question of transnational identity, where many Haitian immigrants continue to remain focused on Haiti and not on the realities in America,” said Georges Fouron, a professor at SUNY Stony Brook who has written about Haitian political participation in the United States. “This is not the case with the second and third generation. I’m not basing my hope on the immigrants themselves, but instead on the children and grandchildren.”

Increased visibility and participation

Despite feeling overlooked, many Haitian-Americans actively work to influence voter turnout by mobilizing their community in the U.S. and even by working through loved ones in Haiti.

In South Carolina, with an estimated 1,106 Haitians, Patrick Gué is currently in the process of helping to form an association, tentatively known as the American Haitian Organization, to start combining political participation efforts by individual Haitians.

“Our Haitian community has to continue to call each other in our state and in our country to motivate us to vote,” said Gué, a Greenville County pastor. “We are even calling people in Haiti to reach out to their friends and family who are U.S. citizens to encourage them to vote.”

An increasing number of Haitian-Americans are beginning to run for office as commissioners and mayors in small cities.

In Georgia, which has a Haitian-American community of 30,763, Haitian-Americans were intensely focused on completing the Census as one way to build cohesion across the state.

“We’re engaging with voters by ensuring that we can count them,” said Saurel Quettan of the Georgia Haitian-American Chamber of Commerce.

With people living in the exurbs, the lengthy commutes make uniting the community a challenge, Quettan said. Nonetheless, the Atlanta resident said, he is optimistic about the growing level of Haitian-American political engagement.

An increasing number of Haitian-Americans are beginning to run for office as commissioners and mayors in small cities he said. Recently, community members walked to a polling site to encourage participation in the elections.

Such increased visibility is part of the solution to be recognized as a significant voting bloc.

“We need to [focus] on ourselves here and encourage each other to vote, so we can continue to participate in the political arena,” said Gué, a Cap-Haïtien native. “If we are organized and start to do things in the community, politicians will see that and come to us.”

The original version of this article was published on the Haitian Times website.