July 14 is Bastille Day. On that date in 1789, tens of thousands of poor people in Paris attacked a hated prison called the Bastille and began the French Revolution. The continual intervention of poor people in the cities and countryside — particularly in Paris — drove the revolution forward.

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels — the founders of communism — lived in that revolution’s afterglow. Lenin and the other leaders of the Russian Revolution studied the French Revolution. Lenin became chairperson of the Council of People’s Commissars, a term derived from the French “commissaire.”

Even the terms “left” and “right” derive from the French upheaval. When the National Assembly met in 1789, the supporters of the king seized the right portion of the chamber and forced revolutionaries to sit on the left. They did this because of an ancient prejudice against left-handed people.

The French Revolution started in Europe, but it belongs to the world. And there would have been no French Revolution without Haiti.

Capitalist riches from enslaved workers

The French Revolution was a capitalist, or bourgeois, revolution. It swept away all the old feudal rubbish, like the remnants of serfdom, that oppressed people. Even the formation of a national market, a necessity for capitalism, had to be fought for.

The capitalist class or bourgeoisie was not a new class. It began its rise centuries earlier in merchant trading. Its earliest attempts to challenge the old feudal order, usually under the guise of religious differences, were thrown back with bloody reprisals.

The Bourbon kings and the big nobles of France were aristocratic parasites who feasted while millions lived in rags. They were symbolized by Queen Marie Antoinette, who, when informed that people had no bread, exclaimed, “Let them eat cake!” referring to the burnt remnants of bread caked inside communal ovens.

During the 1700s, the Bourbon monarchy was increasingly challenged by the bourgeoisie. Its ideologues, led by Voltaire, questioned everything and led the great intellectual movement known as the Enlightenment. Voltaire campaigned against executing people on “the wheel,” a torture device to which people were tied while their bodies were broken, sometimes just for allegedly mocking a religious procession.

But what gave the bourgeoisie its newfound confidence to oppose the monarchy were the profits flowing into its coffers from the labor of people held in slavery.

As C.L.R. James pointed out in his classic “The Black Jacobins”: “Nearly all the industries which developed in France during the eighteenth century had their origin in goods or commodities destined either for the coast of Guinea or for America. The capital from the slave-trade fertilized them; though the bourgeoisie traded in other things than slaves, upon the success or failure of the traffic everything else depended.”

The livelihood of 2 to 6 million people in France — out of a total population of 25 million — depended on slavery and products grown by enslaved people. French possession of Haiti meant it owned the richest colony in the world. Its trade employed 24,000 French sailors on 750 ships.

While Britain had an export trade of 27 million British pounds, the French were close behind with 17 million. The wealth produced by the Haitian people in slavery accounted for nearly 11 million pounds alone.

Liberty seized by enslaved people

The French bourgeoisie declared “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” as the watchwords of their revolution. This is still the motto of France today.

But most French capitalists never wanted to abolish slavery or to grant liberty to Black people kidnapped from Africa who were worked to death in Haiti, Guadeloupe and Martinique.

At that time conditions were such in Haiti that the average life expectancy for a Black person on the island was 21 years. Then, news of the French Revolution reached Haiti and created a political ferment as it became known to people in slavery.

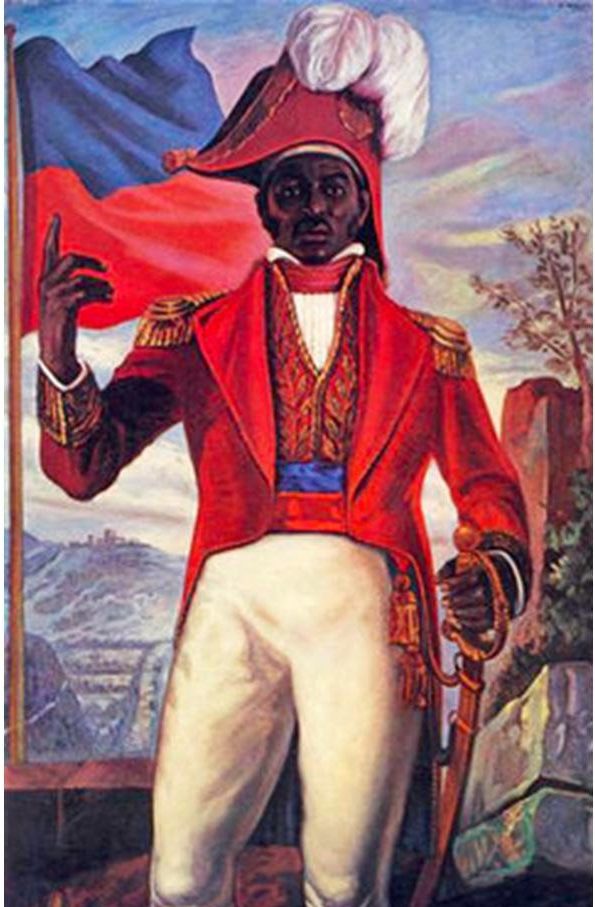

Dutty Boukman, an African originally enslaved in Jamaica, started a revolt in August 1791. Over 1,800 plantations were burned. Boukman was eventually killed, bravely fighting. But new leaders like Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines arose. The rising of Haiti’s enslaved people could not be stopped, and it found support among the French poor.

“The Blacks were taking their part in the destruction of European feudalism begun by the French Revolution,” James wrote, “and liberty and equality, the slogans of the revolution, meant far more to them than to any Frenchman.”

‘The aristocracy of the skin’

While the French Revolution was a bourgeois revolution, it was poor people in the cities and countryside who fought for it. In Europe, there was as yet no modern working class because there were no big industries. The Industrial Revolution had just started in Britain a few years before with the first cotton spinning machines.

Haiti was different. As James pointed out, “Working and living together in gangs of hundreds on the huge sugar-factories which covered the North Plain, they were closer to a modem proletariat [working class] than any group of workers in existence at the time.”

The French poor hated aristocrats and royalty like Marie Antoinette. But it was the “aristocracy of the skin,” as it became known, that became the most hated. Poor people in Paris found it detestable that people could be enslaved, branded and sold like cattle just because of their skin color.

The French poor hated aristocrats and royalty like Marie Antoinette. But it was the “aristocracy of the skin,” as it became known, that became the most hated. Poor people in Paris found it detestable that people could be enslaved, branded and sold like cattle just because of their skin color.

James wrote, “In these few months of their nearest approach to power [the French poor] did not forget the Blacks. They felt towards them as brothers, and the old slave-owners, whom they knew to be supporters of the counter-revolution, they hated as if Frenchmen themselves had suffered under the whip.

“It was not Paris alone but all revolutionary France. ‘Servants, peasants, workers, the laborers by the day in the fields all over France were filled with a virulent hatred against the ‘aristocracy of the skin’ [James was quoting a supporter of slavery]. There were many so moved by the sufferings of the slaves that they had long ceased to drink coffee, thinking of it as drenched with the blood and sweat of men turned into brutes.”

As the French Revolution went forward, those bourgeois political leaders who opposed radical measures became known as Girondists. They were named for the region surrounding the French port of Bordeaux. Like Liverpool in England, Bordeaux’s economic life depended on the slave trade.

The opponents of the Girondists were known as Jacobins. Most schoolbooks slander Jacobins like Maximilien Robespierre or other radicals like Jean-Paul Marat as bloodthirsty “terrorists.”

But most of the Girondist leaders who talked so grandly about liberty didn’t want to abolish slavery. It was only when Robespierre and the radical Jacobins were in power that slavery was formally ended in all French possessions by the decree of Feb. 4, 1794.

This was a historic measure by France’s National Convention, but it only confirmed the freedom that had already been seized by the enslaved people themselves.

Defending the revolutions

The French Revolution was opposed by all of feudal Europe and by Britain, its commercial rival. Like the Russian Revolution more than a century later, France was invaded on a dozen fronts. The Duke of Brunswick, commander of the Allied Army (principally Austrian and Prussian), issued a manifesto threatening the destruction of Paris.

Although Britain bankrolled some of the armies invading France, its own army was absent. That’s because it was invading Haiti. This move was a disaster for the British ruling class. “By the end of 1796, after three years of war, the British had lost in the West Indies 80,000 soldiers including 40,000 actually dead,” wrote James.

If the British army that invaded Haiti had marched on Paris along with other European powers, the French Revolution might have been crushed. By defending their own freedom in a battle with British invaders, the Haitian people also defended the freedom of 25 million people in France.

“It was the decree of abolition, the bravery of the Black [people], and the ability of their leaders, that had done it,” wrote James. “The great gesture of the French working people towards the Black slaves, against their own white ruling class, had helped to save their revolution from reactionary Europe. Held by Toussaint and his raw levies, singing the Marseillaise and the Ça ira [two revolutionary songs], Britain, the most powerful country in Europe, could not attack the revolution in France.”

In “A History of the British Army,” J.W. Fortescue concluded that people who had been enslaved “had practically destroyed the British Army.” He admitted that “the secret of England’s impotence for the first six years of the war may be said to lie in the two fatal words, St. Domingo [the old name for Haiti].”

Two centuries of revenge

After the French Revolution, the radical Jacobins were overthrown and many were executed. Napoleon Bonaparte eventually seized power and became a military dictator.

Napoleon defeated one European feudal army after another. But he couldn’t conquer Haiti. Napoleon sent an army to Haiti commanded by his brother-in-law, Charles Leclerc, and Toussaint Louverture was kidnapped and died in a French prison.

But as Leclerc wrote to a French government minister: “It is not enough to have taken away Toussaint, there are 2,000 leaders to be taken away.” Leclerc died in Haiti knowing he was defeated. (Aldon Lynn Nielsen, “C.L.R. James: A Critical Introduction”)

Despite massacres that included drowning a thousand Black people at a time, as well as public burnings and hangings, the French army suffered a worse defeat than the British. Out of 34,000 French troops, 24,000 died.

Dessalines declared Haiti’s independence on Jan. 1, 1804. But the world capitalist class has never forgiven Haiti for its revolution. U.S. slave masters had nightmares about leaders in the mold of Dessalines, like Nat Turner who led an 1831 uprising of enslaved people in Virginia. Haiti is still deliberately kept the poorest country in this hemisphere by the United States and other capitalist countries.

But the Haitian Revolution changed history forever.

Tear down the walls

French capitalists use Bastille Day to glorify French colonialism. But socialist revolutionaries should celebrate Bastille Day by demanding that the more than two million prisoners locked up in U.S. bastilles be freed, starting with Leonard Peltier, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Dr. Aafia Siddiqui, and the MOVE 9.

Bastille Day should also be celebrated because of the Iraqi Revolution that overthrew the U.S.- and British-backed monarchy on Bastille Day — July 14, 1958. Capitalists never forgave Haiti’s revolution and haven’t forgiven Iraq’s people for taking over their own oil. The Pentagon has invaded Iraq twice and still occupies it.

The U.S. capitalist class is as obsolete and useless as the French aristocracy was 228 years ago. Capitalists want to take away health care, privatize Social Security and cut wages even further. A socialist revolution is needed just to stop capitalism from cooking the earth.

The multinational working class in the United States will be forced to rise, as the French and Haitian masses did. An absolutely necessary requirement for success is that millions of white workers, part of this multinational class, break with racism. They need to see, and will see, that they are being used as political cattle by the wealthy and powerful, like Donald Trump, who actually despise them.

Tear down the Bastilles! Down with the aristocracy of the skin! Reparations for Haiti!

This article was first published in “Workers World” newspaper. It draws largely on C.L.R. James, “The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution.”