(The third of three parts)

(Part 1) (Part 2)

Haiti’s mineral wealth is still protected by a moratorium on mining activities imposed by the Haitian Senate five years ago, and a new mining law drafted in 2017 remains in a drawer somewhere. Nonetheless, tensions are rising between mining companies, the Haitian State, and civil society. For decades, many have salivated for the riches hidden in Haiti’s subsoil. Frustration is high. And in this uncertain climate, almost anything can happen.

A development opportunity, according to the Haitian State

Opinions are divided on what to do with and how to use Haiti’s mineral resources. Civil society and the Haitian state remain divided on the issue. And so far, there has never been a national debate.

For Haitian authorities, the development and exploitation of mineral and energy resources can “contribute to the development of conditions necessary for the growth of national wealth in the context of the country’s economic and social development plans.” This thesis has never been accompanied by any details.

If social benefits compared to costs will be so broad, why are studies on socio-economic and environmental effects never published?

Regarding the conflict between companies, we contacted the head of the office responsible for mining research, controlling mines and sand quarries, and developing energy resources, the engineer-geologist Claude Prépetit, director general of the Bureau of Mines and Energy (BME). He did not answer.

However, in a lecture given at the National School of Applied Geology (ENGA) in June 2018, Prépetit commented generally on the state of the sector to stop some rumors circulating in the media and in some communities. He continues to say that it is impossible to mine on the sly and that a metal mining operation is not taking place at this time.

“People say anything,” he said. “It is said that, despite the resolution, the companies continue to mine. It’s not true. There is no mining in Haiti. Since the Senate resolution in 2013, all companies have left. They are waiting for the state to say the word to return. Nonetheless, this resolution has no binding force, because it was not published in Le Moniteur. So, it has no legal force.”

Credit: Milo Milfort

Might this mixed message convince the companies to finally return to Haiti to start operations?

In a short email interview in June 2018 with Enquet’Action, Mr. Prépetit said to anyone who wants to hear him: “We are for the development of our mining potential, but it is necessary to create the necessary conditions so that the revenues generated by the mines can be used for the country’s development, particularly local sustainable development while taking into account the negative impacts on the environment, which must be minimized as much as possible. To this end, any mining should be subordinated to a strengthening of the State’s institutional capacities and to a strict respect of the laws in force “, he said, admitting openly that his position is idealistic.

A Colonial Project Denounced by Civil Society

The Resource Générale Corporation (RGC), which also is known as VCS Mining, says it wants to “help Haiti to become the Pearl of the West Indies again”. This was enough to reinforce the thesis of the Mining Justice Collective (Kolektif Jistis Min in Kreyòl) that the mining project is “colonial”, given that this nickname was attributed to the former Saint Domingue, a colony dedicated to the production of wealth for France based on slavery.

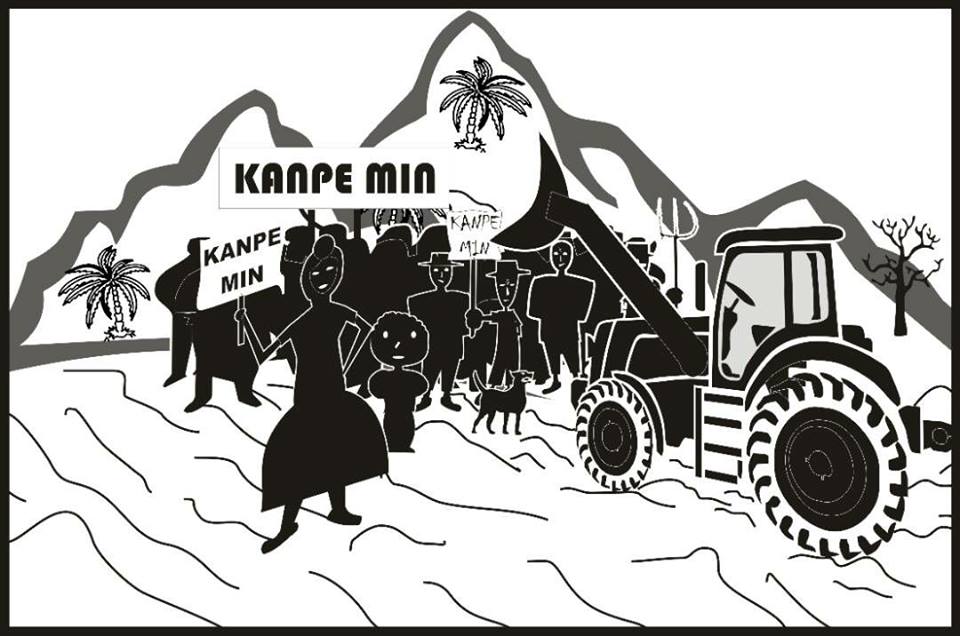

The KJM is a coalition of more than 20 Haitian social movement organizations fighting against open-pit mining – especially metal mines.

activists say no to “any mining project in Morne Pelé” and advocate instead for the establishment of agrarian reform, agricultural roads, hospitals, schools, reforestation, and drinking water.

“3D landed in communities to start working, despite the moratorium of the Haitian Senate,” said Peterson Dérolus, KJM’s head. “And communities have risen up to say no to mining. It was suddenly learned that the 3D Company is asking VCS to renegotiate their contract. Nobody is aware of the terms of the contract between them, despite the fact that it concerns the country’s resources.”

For Mr. Dérolus, VCS and 3D are multinational companies that have a long history behind them. The 3D firm, coming from Australia, is said to have already left many communities with great environmental difficulties. The same for VCS. He also denounces the fact that companies are constantly changing their names so as to confuse communities about their past experiences in other communities.

“The only thing the Haitian people have to gain from this conflict between companies is much more time to build their strength, either to stop projects or to delay them. Companies have nothing to lose. But the people and communities targeted, yes,” he says, adding that previous experiences show that mining companies are taking advantage of unclear situations to find lucrative contracts.

KJM’s head continues to believe that sometimes companies contribute to creating trouble in order to divert people’s attention, while they plunder resources.

“The mining project violates the country’s constitution, the right to information, the right to a healthy environment, and the right to life,” he says.

Haiti is far from being able to control an open-pit mine.

In several press reports, the KJM asserts that mining brings economic, environmental, and eco-systemic destruction, unemployment, impoverishment, and suffering in general wherever this scourge goes, but especially among workers, peasants, and farmers, the most impoverished popular classes.

At the same time, an open letter published this year by a dozen Haitian institutions and organizations – including churches and local authorities living in Morne Pelé in Haiti’s North – shows the communities’ “proven discontent with the mining companies’” project. In this letter addressed to Haiti’s local and national authorities, these activists say no to “any mining project in Morne Pelé” and advocate instead for the establishment of agrarian reform, agricultural roads, hospitals, schools, reforestation, and drinking water.

Job creation is often the leading argument advanced by mining companies and authorities to convince local people and communities to accept the development of a mining project. This developmental discourse focused on international capital is the pretext that is also used to establish free trade zones in Haiti in order to continue to exploit the poorest and to discourage any impetus for the development of national production.

For about 10 years now, this discourse has taken on new forms, presenting mining as the only way to get Haiti out of underdevelopment.

This argument is criticized by organizations of Haiti’s social movement. “This country’s history and that of other peoples show that these arguments are lies. These are words to confuse (vire lòlòj moun – in Kreyòl), poisoning the spirit and consciousness of people to continue to perpetuate these projects of plunder,” says the KJM, which is categorically against any exploitation of metal mines in Haiti.

Between the KJM’s radical position and the idealistic position of the Bureau of Mines and Energy (BME), one reality is clear: Haiti is far from being able to control an open-pit mine.

Perhaps it will never be possible to reconcile national interests with those of mining companies that believe only in wealth, but a change towards a progressive and popular system in Haiti is not for tomorrow in a country where the ability and will to change things is difficult.

In this cold war, will the KJM succeed in duplicating the Salvadoran model where in April 2017 the Salvadorean people banned the mining of metals like gold and silver, placing the environment (including water, forests, and food) and the health of their fellow citizens above financial considerations?

ENQUET’ACTION is an online media of journalistic investigation, of multimedia journalism, and of deep-digging journalism, created in February 2017 in Port-au-Prince and officially launched in June 2017. Focused on quality journalism that believes in free access to information, it aims to become an indispensable source of information for national and international media, as well as for the public. It was born from the desire to reconnect with the fundamentals of journalism that seeks the quest for truth to allow the press to truly play its role of counter-power.

Translated from the original French by Kim Ives