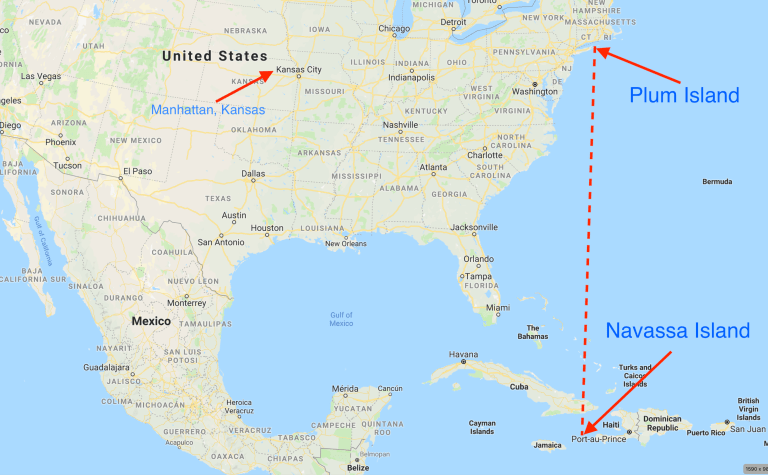

Navassa Island (Ile de la Navasse) is located in the center of the Caribbean Sea, 46 miles west of the Haitian town of Jérémie. Spain ceded the small two-square-mile uninhabited island to France under the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, and it became part of Haiti after its 1804 independence.

But in 1858, the United States under President James Buchanan, laid claim to the island through the Guano Islands’ Act, under which Washington gave itself the right to seize any uninhabited island on earth in order to mine huge deposits of bird dung (guano) for its value as a nitrogen-rich element in fertilizer and gunpowder, both key to the U.S.’s 19th century development.

Haiti has never recognized the U.S. seizure of La Navasse, so it remains disputed territory.

This has not stopped the U.S. from unilaterally using the island. After mining guano there until 1901, the U.S. built a lighthouse on La Navasse which functioned from 1917 until 1996. A U.S. Navy Seal Team in helicopters also used the island as a staging area for its Feb. 29, 2004 kidnapping of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide from his home in Tabarre, outside Port-au-Prince, Haïti Liberté learned from an anonymous source involved in the operation.

As the following article published this week by CovertAction Magazine explains, La Navasse was also apparently used by the U.S. to launch a biological attack against Cuba in 1971, when the CIA tried, unsuccessfully, to unleash an African Swine Fever Virus epidemic there.

Today, Washington is again co-opting Haiti for aggression, using the hugely unpopular regime of Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse as its principal Caribbean ally in its campaign to oust Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro. Although the Duvalier dictatorship may have been unaware that the U.S. was using Haiti to launch an attack on Cuba in 1971, this article reveals how La Navasse, a speck of Haitian territory, has been exploited as a resource and a platform in Washington’s efforts to control the Caribbean.

Kim Ives

“Cuban Outbreak of Swine Fever Linked to CIA” headlined a Jan. 9, 1977, article by Drew Featherston and John Cummings in Newsday, a Long Island, New York, daily paper. It began:

“With at least the tacit backing of U.S. Central Intelligence Agency officials, operatives linked to anti-Castro terrorists introduced African swine fever virus into Cuba in 1971. Six weeks later an outbreak of the disease forced the slaughter of 500,000 pigs to prevent a nationwide animal epidemic.

“A U.S. intelligence source told Newsday he was given the virus in a sealed, unmarked container at a U.S. Army base and CIA training ground in the Panama Canal Zone, with instructions to turn it over to the anti-Castro group.

“The 1971 outbreak, the first and only time the disease has hit the Western Hemisphere, was labeled the ‘most alarming event’ of 1971 by the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization. African swine fever is a highly contagious and usually lethal viral disease that infects only pigs and, unlike swine flu, cannot be transmitted to humans. There were no human deaths in the outbreak, but all production of pork, a Cuban staple, came to a halt, apparently for several months…

“The U.S. intelligence source said that early in 1971 he was given the virus in a sealed, unmarked container at Ft. Gulick, an Army base in the Panama Canal Zone. The CIA also operated a paramilitary training center for career personnel and mercenaries at Ft. Gulick…

“Another man involved in the operation, a Cuban exile who asked not to be identified, said he was on the trawler where the virus was put aboard at a rendezvous point off Bocas del Toro, Panama. He said the trawler carried the virus to Navassa Island, a tiny, deserted, U.S.-owned island between Jamaica and Haiti. From there, after the trawler made a brief stopover, the container was taken to Cuba and given to other operatives on the southern coast near the U.S. Navy base at Guantanamo Bay in late March, according to the source on the trawler.”

It was an explosive story, reprinted in newspapers across the country. The CIA officially denied it six days later, in response to a request from the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, but the Newsday reporters had cited so many corroborating sources, with such specific details, that the denial was not widely believed.

The most compelling reason for trusting the credibility of the Newsday report was that the only place in the Western Hemisphere where the virus was known to have been kept before the outbreak in Cuba was at the secret Plum Island Animal Disease Center (PIADC) laboratory off the eastern tip of Long Island, where local Newsday reporters had been cultivating sources since the one and only time reporters had been allowed inside in October 1971.

AP

Plum Island had hosted the U.S. Army Chemical Corps base at Fort Terry from 1952 to 1956. According to Deadly Cultures: Biological Weapons since 1945 by Mark Wheelis and Lajos Rózsa, the mission at Fort Terry was “to establish and pursue a program of research and development of certain anti-animal (BW) agents.” (a.k.a. biological weapons) The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) took over from the Army in 1956.

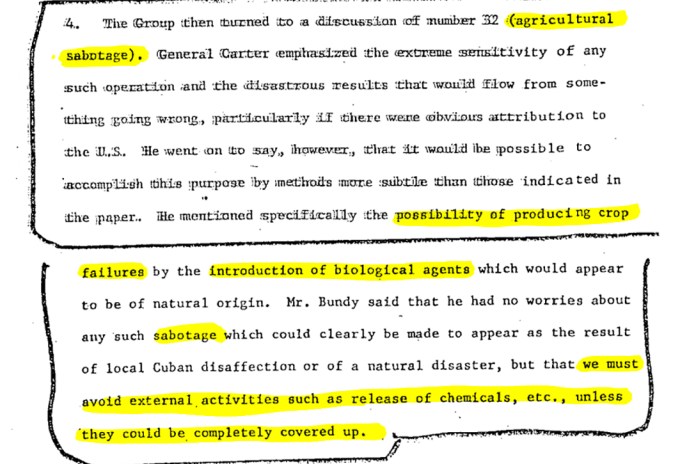

President Richard Nixon ordered biological weapons research to cease in 1969, but in 1975 the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence revealed that the CIA had continued to maintain a stockpile of biological agents and toxins in violation of the order.

Newsday had made no mention of Plum Island, perhaps to protect its reporters’ sources, but other reporters quickly made the connection. In the 2004 book, Lab 257 by Michael Christopher Carroll, the author wrote:

“According to the federal government, Plum Island is the only location in the United States where African swine fever virus is permitted. No one will say on the record that the virus for the Cuban mission was prepared on Plum Island and sent to Fort Gulick. However, given the frequent traffic between Plum Island and Fort Detrick, Maryland samples – with or without the USDA’s knowledge of the ultimate purpose – could have been sent to Fort Detrick for transshipment to Fort Gulick. . . .”

Norman Covert, Fort Detrick’s historian, shows how the CIA could easily have been involved – and unwittingly co-opted Plum Island. “There were CIA people who infiltrated the [Fort Detrick] laboratories. They did their own work with LSD and other psycho-illnesses. They had their own cell there—they worked on their own, and I suspect a very small circle of people knew that.” This type of information isolation—informing people of project details on a need-to-know basis—is the brand of secrecy that might have been used to poison Cuba’s food supply with germs. Compartmentalization of each step made Plum Island an unknowing accomplice when it trafficked in viruses between Fort Detrick and elsewhere.

Efforts to explain away the outbreak as a natural occurrence do not hold up to close examination. The theory that food wastes from Spanish aircraft were fed to domestic pigs fails to address that Cuba, like the United States, had always kept their nation disease-free through strict importation quarantines. Cuban investigators claim ASFV broke out simultaneously in two distant locations; germ warfare experts say that contemporaneous sites of infection are unnatural and point to a deliberately caused outbreak. Because it is impossible to disprove, the logic of a methodical scientist dictates that a germ warfare attack cannot be ruled out. CIA assassination plots (some of which involved germs) and the Bay of Pigs invasion stand as acknowledged covert acts by the United States government to force regime change upon Cuba.

Forty-nine years after the biological warfare attack on Cuba, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) continues to operate the Plum Island center while DHS builds a new home for the laboratory at Manhattan, Kansas, scheduled to open in 2021, to be known as the National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility (NBAF).

USDA will own, manage, and operate the new facility, as it formerly did at Plum Island. According to the DHS website, “The federal government will execute a plan to provide for seamless transition of the agricultural defense mission from PIADC to the NBAF that includes an overlap of operations to make certain there is no interruption of the critical science mission and operational capabilities.”

Today, as in 1977, the government officially denies sponsoring an offensive biological warfare program. Further, today, as then, it asserts claims of security that prevent any effective independent verification and critical oversight. But a scarcely noticed detail of the Newsday report offers grounds for a fresh look at the evidence of the 1971 attack:

“…the trawler carried the virus to Navassa Island, a tiny, deserted, U.S.-owned island between Jamaica and Haiti. From there, after the trawler made a brief stopover, the container was taken to Cuba…”

Despite Haiti’s objection since 1858, Navassa Island is the original United States overseas possession claimed in 1857 and officially declared a U.S. “appurtenance” in 1859. My Navassa research file includes a previously unreported document that lends circumstantial support to the Newsday story – a 1986 typescript draft of an article by U.S. Coast Guard lighthouse historian Neil Hurley titled “Navassa Island Light, ‘Where Chickens Only Miraculously Survive the Attacks of Lizards.’”

When Hurley’s article appeared in the Winter 1988 issue of The Keeper’s Log, under the title “Navassa Lighthouse,” these two sentences from his earlier draft were omitted: “In 1971, a U.S. Navy Research team visited the Island to look for animal diseases that could be transmitted to man. They found one bird carrying malaria.”

It might be a coincidence, but it seems remarkable that the Navy was investigating the possible presence of biological toxins on Navassa Island at about the time that agents were reported to have brought dangerous microbes to Navassa for a biological attack on Cuba.

By itself, the two-sentence unpublished excerpt from Hurley’s monograph doesn’t amount to much. However, two U.S. Navy missions to Swan Island off the coast of Honduras in 1960 and 1961 provided essential logistical support for the CIA’s communication and propaganda center for the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion.

The unpublished lines in Hurley’s typescript leave this lingering question unanswered: Did the 1971 U.S. Navy mission to Navassa Island provide support for an African swine fever attack on Cuba, a decade after two Navy missions transported supplies to another Caribbean island for the CIA’s failed invasion of Cuba?

Ken Lawrence is an investigative journalist and veteran writer for CovertAction Magazine. Since the magazine’s founding in the late 1970s, Lawrence regularly penned the popular column “Sources and Methods.”

Here’s a good one for you Jack and I might be able to add to the story you just sent me. In 1985 two cuban guys came to hear me perform in palm springs at sinatra’s favorite restaurant named Patti Z’s – is where i sang for his wedding anniversary. These two guys where hired by the cia to try to kill castro using some kind of poison and they were found out and locked up and our government paid a hundred and seventy five thousand dollars each to get them freed and back to america. One of the guys made a drug run for the philadelphia mafia family and they put him on a 85 foot forward a fishing trawler and drop him off in aruba in the caribbean and from there they went to colombia and there nearly got their butts shot off while they were trying to load the ship with hundreds of bags of marijuana and a battle took place on the beach as they watched from their ship and people were getting shot so they left with only half a load. On the way back to florida we were hit by a hurricane and they had to abandon the boat. my cuban friends name was octavio gomez. In his hurry to get off the boat and swim to and island i forgot his wallet and when the coast guard down the ship adrift they found his wallet. When he arrived back to miami to is home he received a call from the philly buffy a saying he bouched the deal and they also told them the feds we’re looking for him. He and his wife and two kids jumped in their car and then ended in palm springs. The story doesn’t end there…. the guys asked me if i would put them together in a meeting at my house with sinatra’s chef Al Bonita who was my adopted godfather. He only killed one guy i know of in brooklyn and service 7 years. At my house the cubans laid a brick of cocaine and they ask for 54,000 dollars and bonita responded saying they would only pay 20k. The deal fell through. Then the cubans showed me a warehouse filled to the roof with green plastic trash bags full of the weed. Gomez was scared to death as well as his family so i arranged to have them go to sacramento california and meet with the assistant pastor of a huge assembly of god church with 5,000 members . i once performed there. they hid him away and his family and later he became a minister. I am guessing the guys had to do with navassa island.

During the time i was getting ready to sue america a california attorney living and practice in in jamaica and who owned a scuba dive shop contacted me and said he was interested to represent me in my lawsuit against. I agreed. said he would some phone calls to DC. Next day you called me that to say he was inform to back away from me. He told me in about 1976 it was hired by the cia and some other kind folks he died with other drivers around navassa to see if nuclear submarines could hide in the underwater catacombs under the islands it and he said the subs were too big.

How’s that for the making of a book you and i could write and have it turned into a major film