On Sun., Feb. 23, the first day of Haiti’s famous annual three-day Mardi Gras Carnaval celebration, a six-hour gun battle between Haitian police and soldiers on Port-au-Prince’s central square signaled the dramatic return of the revolutionary uprising which all but paralyzed Haiti for three months last autumn.

Three people were killed in the firefight – one soldier, one policeman, and a 17-year-old boy – and at least 12 were wounded.

Just as common soldiers were drawn into the Russian Revolution a century ago, Haiti’s lower ranking police men and women are increasingly siding with the Haitian people in their demands that President Jovenel Moïse resign and that Haiti’s dysfunctional economic system be radically changed.

Since last October, Haitian National Police (PNH) “agents” (as police officers in Haiti are called) have held several large demonstrations to demand better salaries, work conditions, health care, and a union. In November, in defiance of police regulations, they formed the Union of Haiti’s National Police (SPNH), headed by an outspoken woman, Yannick Joseph, 34.

But the force’s high command, under the leadership of Police Chief Normil Rameau (whom Moïse appointed last August), announced an investigation and suspended Joseph and four other union-organizing cops on Feb. 7, sparking a rank-and-file mutiny.

That day, Joseph refused to surrender her PNH badge, uniform, and weapon, and SPNH partisans allegedly busted up the Police Inspector General’s office, spray-painted the union’s initials on police vehicles, and fired their weapons in the air.

“The SPNH is now engaged in working side by side with the population.”

On Mon., Feb. 17, hundreds of pro-union police men and women wearing red T-shirts marched from the international airport to police headquarters in Pétionville, where they held a militant rally.

“I am not afraid,” Yannick Joseph told the crowd. “My roots are not afraid because my birthday is Feb. 7, 1986 [the day dictator Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier was overthrown]. We have nothing more to fear today. The SPNH is now engaged in working side by side with the population. We will never fight against the people because we police agents are the children of poor market women.”

Later that evening, the Carnaval stands on the capital’s central square, Champ de Mars, were set ablaze. Haitian authorities accused the rebellious cops of the deed, but they denied responsibility.

The PNH leadership then definitively fired Joseph and her four comrades – Gédéon Monbrun, Abelson Gros Nègre (Agent 2), Jean Elder Lundi (police inspector), and Lens Lamarre (Agent 1) – on Tue., Feb. 18.

The pro-union police agents, backed by civilians, held another demonstration on the first day of Carnaval. When the marchers arrived at the Champ de Mars in front of the National Palace and the president’s reviewing stand, witnesses say that soldiers of the Armed Forces of Haiti (FAdH), guarding the stand and their headquarters, opened fire on policemen and women at around 1 p.m.. The police forces returned fire. Chaos in downtown Port-au-Prince ensued. Skirmishing continued throughout the afternoon as masked gunmen dashed around, taking cover to fire from behind trees, cars, concrete benches, and curbs. Crowds of civilian onlookers followed the action from a safe distance, sometimes exclaiming, jeering, or dashing into the fray.

“No money for police officers but enough money for carnival” was one of the protestors principal chants. The Moïse regime is reported to have spent up to 100 million gourdes (about US$1.12 million) for Carnaval.

One of several recently delivered armored vehicles of the Special Unit to Guard the National Palace (USGPN) rolled out into the square, apparently to intimidate the rebelling police. Instead, SPNH cops surrounded and took control of the vehicle, forcing its occupants to surrender.

In official statements, the Haitian government condemned the confrontation as “a coup attempt” and “an attack against freedom and democracy.”

“Terror reigned in certain areas,” one statement said. “Streets were obstructed and there was a war-like situation on the Champ de Mars, where heavy weapons fire was heard almost all day.”

Jovenel Moïse resurrected the FAdH in 2017. It had been established as a proxy force by the U.S. Marines after they ended their 19-year military occupation of Haiti in 1934. Former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide had demobilized the army in 1995 for its widespread human rights abuses, drug trafficking, and repeated role in carrying out coups d’état during the 20th century. It had remained demobilized for 22 years.

“there was a war-like situation on the Champ de Mars…”

After Sunday’s violence, Haitian authorities, in a rare move, cancelled Carnaval in the capital. In the northern city of Cap Haïtien, Jovenel’s mentor, former president Michel “Sweet Micky” Martelly had been scheduled to give a concert on Sat., Feb. 22, but it had to be cancelled due to palpable popular hostility against him and the government. Carnaval stands were also burned in Cap, and the Feb. 23 parade was cancelled due to gunfire and rain. Sweet Micky rode a float through town on Feb. 24, but the other bands boycotted the parade that day due to his presence. The final and third day of Mardi Gras, Feb. 25, saw the other bands’ floats make the “défilé” through town, but not Sweet Micky.

On Sunday, the FAdH issued a statement claiming it was attacked in its headquarters by the police, killing soldier Jean Baptiste Dorvil and wounding Corporal Lucien Cerdieu and soldier Audate Castin.

“We bitterly deplore such actions which can only be the work of individuals oriented towards the destruction of the country, and their own,” the Army’s statement said.

The fledgling Haitian Army has just over 500 soldiers, while the PNH is a force of about 16,000.

On Mon., Feb. 24, Police Chief Rameau held a press conference to announce the formation of a five-member Facilitation and Dialogue Commission, aimed at re-establishing “institutional stability and public peace.” The commission’s members are Inspector Generals Jean Gardy Muscadin and Smith Payot, curator Magalie Belneau, Jean Mary Rosa Leonard (Agent 4), and Michelson Fortuné (Agent 3). They are charged with submitting a report in two weeks.

The same day, the SPNH leadership indicated their willingness to negotiate with authorities, but with the precondition that the fired police union leaders be reinstated.

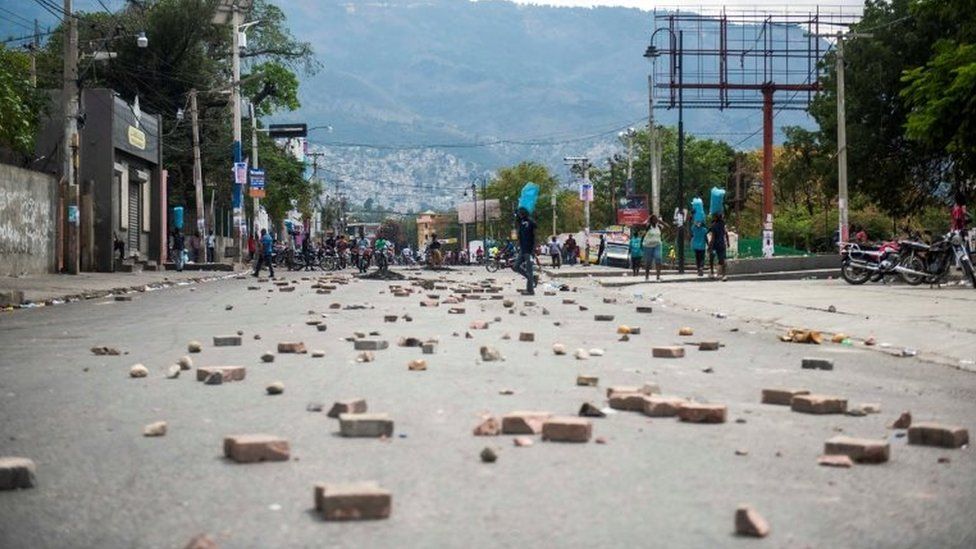

Also on Monday, demonstrators supporting the police and calling for Jovenel’s resignation blocked many streets in the capital by covering them with bricks, rocks, piles of burning tires, and overturned carts and furniture.

Tensions remain high in Haiti. With Washington’s backing, during the months of December and January, the Moïse regime carried out a charade of calling for dialogue and a “national unity” government, but the Haitian opposition and people rejected the overtures. Many saw it as a ploy to buy time until Jan. 13, when Moïse effectively dissolved the Parliament, thereby empowering himself to rule by decree.

Now Moïse stands alone to face the reflaring fury of the Haitian people, but this time, the masses are joined increasingly by rebellious police rank-and-file.