(Part 1)

This is part two of a three-part series by The Canada Files on Canadian imperialism in Haiti versus the fight of the Haitian grassroots to free themselves from Western occupation.

The “large coalition” which Montana’s spokespeople often refer to has shrunk considerably since their Accord was initially announced in August 2021. Labor unions and political parties have withdrawn support. It is unclear what fraction of the “civil society” organizations, unions, peasants groups, and human rights outfits which initially supported Montana continue to do so.

First, Fanmi Lavalas (FL) withdrew support for the BSA (Bureau de Suivi – the Montana Accord’s Monitoring Office, its governing body). They complained of factionalism in the selection process for the interim-elect President and Prime Minister.

Next, MOLEGHAF, an anti-imperialist popular organization withdrew support for the Montana Accord entirely. In a May 2022 interview with Haiti Liberté, MOLEGHAF’s leader Oxygène David explained that when they “left the Montana coalition, the union CNOH [National Confederation of Haitian Workers] left, and many popular organizations no longer recognize the Montana Accord.”

In David’s view, “the Montana Accord did nothing more than plunge the masses deeper into exclusion, poverty, and misery.” The leadership behind Montana “never believed in mass mobilization nor called for popular mobilization. Montana did nothing but put a brake on the popular mobilization. They have a wait-and-see attitude, waiting for the U.S. imperialists to give them a green-light and facilitate the political change they want.”

In an Aug. 1, 2022 press release, former senator Antonio Chéramy suggested Montana’s leadership drop the dialogue process with Washington and the PHTK because it was leading nowhere. Chéramy also proposed that BSA members convene all of the Montana Accord’s signatories to engage in mobilization movements capable of ousting Henry’s coalition.

Montana’s leadership does seem to have lost the support of major labor unions in Haiti. While these unions support the spirit of building a broad-based coalition, their January 2023 joint-declaration did not mention the Montana Accord.

Similarly, La plateforme d’organisations paysannes, a coalition of four peasants organizations named 4G Kontre (Four eyes meet), themselves signatories to the Montana Accord, pleaded with Montana’s leadership to complete negotiations with various groups in the coalition. In a January 2023 interview with Alterpresse, they argued this needed to organize “all types of mobilizations” demanding the “installation of a transitional government.”

Two weeks later, it was apparent 4G Kontre was exasperated with Montana’s leadership. In a Feb. 1, 2023 interview with Alterpresse, Chavannes Jean-Baptiste, a spokesperson for one of the peasants groups who make up 4G Kontre, said that, compared to Henry’s December 21 Accord, Montana has a “democratic basis.”

Nonetheless, Jean-Baptiste said “the most visible political protagonists are still unable to agree on an Accord between them.” He called for “a national awakening” that focused on “a major national dialogue, with a view to leading to a national agreement.”

Indicating that while 4G Kontre supported the initial coalition (Commission pour la Recherche d’une Solution Haïtienne à la Crise – CRSHC) and the Montana Accord, they had lost faith in Montana’s leadership.

These declarations, suggestions, and pleas seem to have been ignored by Fritz Alphonse Jean, Ted Saint Dic, Magali Comeau Denis, and other leaders in Montana’s two governing bodies – the BSA and CNT (National Transitional Council). They did refuse to continue negotiating with Henry. Rebuilding their coalition and building solidarity with the Haitian people, however, wasn’t in the cards.

As Prof. Chalmers Larose explained to Le Devoir in a recent interview, Montana’s “basic unity has been broken,” citing “tactical” differences between the members. Larose explained that the Montana “Accord has reached a phase of obsolescence.”

Other Haitian academics concur with this assessment. Speaking to Pascal Robert on the Mau Mau Hour podcast, Prof. Paul Mocombe commented that he does “not believe the Montana Accord represents the interests of the Haitian people.” Mocombe describes Montana leadership as a “group of technocrats who are looking to be in the good graces of the CORE group.”

While support for Montana’s leadership was crumbling in Haiti, interest abroad was growing.

By late 2022, U.S. think-tanks, diplomats, and journalists were actively promoting the Montana Accord as the best option for progress in Haiti, ignoring the reality that the coalition behind the Montana Accord had crumbled.

Montana’s rise in popularity in the West

Over the past 18 months, Montana’s popularity has increased among some in the halls of power outside Haiti, where it is seen as a preferable alternative to Henry’s lumbering and illegitimate rule.

Some prominent liberals and“Haiti watchers” in the U.S. and Canadian mainstream media view the Montana Accord as the best, or only, alternative to Henry. They seem unaware that Montana’s support has crumbled in Haiti.

Reporters like The Nation’s Amy Wilentz described the Montana Accord as “the Haitian Solution to the Crisis,” claiming the Accord’s coalition is a “vast network of Haitian organizations.” The Washington Post shared Wilentz’s enthusiastic support for Montana, suggesting that its leadership “deserve[s] a role in determining Haiti’s future; Washington could give them that.”

In Canada, Le Devoir’s Guy Taillefer argued that the Canadian government should support the Montana Accord, which he describes as a “broad coalition of political parties and civil society organizations.”

Consequently, while speaking on behalf of Montana, Jean is not challenged on the coalition’s current state. The narrative that Montana represents a current broad-consensus among Haitians is repeated over and over again, despite a lack of evidence.

Reporting on the Montana Accord’s popularity among Haitians has been scant over the past 18 months. The Haitian Times, for example, took over one year to publish a link to the text of the Accord itself. Coverage in the Haitian French language press provides few details and context for understanding the current state of Montana’s coalition, or the support this coalition has in Haiti and the diaspora. As one protestor at the Debout pour la Dignité demonstration explained: “It is not recognized by Haitians. It’s not going anywhere,” while another protestor said “I don’t even know what the Montana Accord is.”

Top U.S. diplomats have also chimed in on Montana. Former U.S. Ambassador to Haiti James Foley, who was actively involved in the 2004 coup against Aristide, claimed that the coalition behind Montana represents “an impressively broad spectrum of Haiti’s civil society” and a “singular hope for progress.”

Writing for the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), Susan Page, who led MINUJUSTH, the UN’s last Chapter 7 mission in Haiti and MINUSTAH’s successor, wrote that the U.S. “should view the Montana Accord as the natural starting point for its new strategic approach for Haiti precisely because it is a Haitian-formulated agreement.” By supporting the Montana Accord, “the United States could rally other bilateral and international partners, many of whom are part of the Core Group, that wield enormous power and influence in the country, to work directly with Haitian civil society actors.”

Despite the enthusiasm in Western capitals, the editors at Le Nouvelliste, Haiti’s establishment daily newspaper, seem to understand Montana leadership’s role as controlled opposition. For a year-end retrospective in January 2023, it published a front page caricature depicting three sinister individuals stirring a cauldron filled with the bodies of dead Haitians.

The cauldron’s three stirrers are Ariel Henry, Magalie Comeau Denis, and Canadian ambassador to Haiti Sébastien Carrière.

The Canadian parliament’s standing committee report on the crisis in Haiti

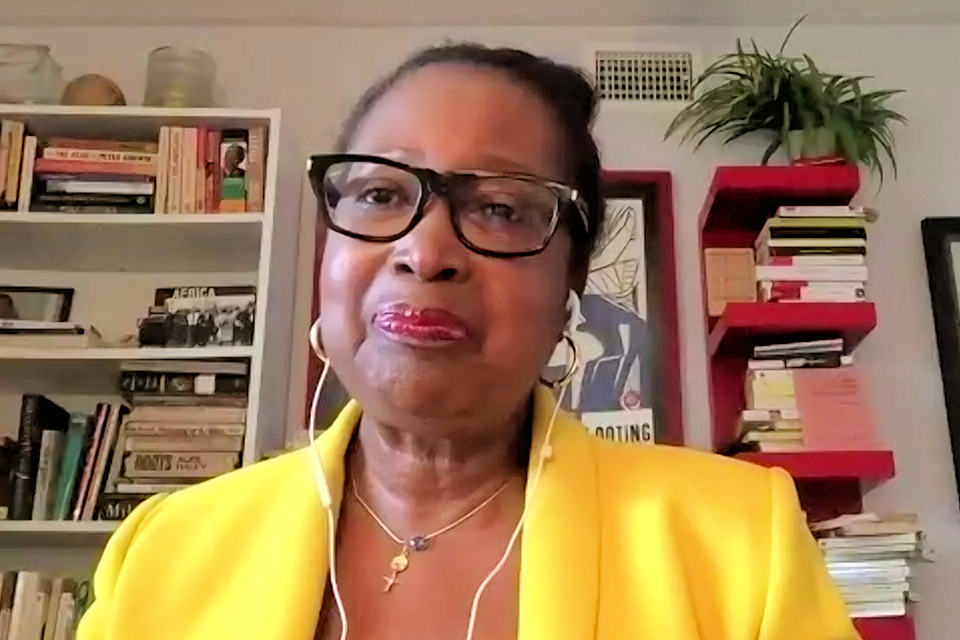

Monique Clesca, another spokesperson for the Montana Accord, who has a background in diplomacy, recently spoke to a Canadian Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development. She was one of several guests including Renata Segura (Associate Director of Latin America and Caribbean, International Crisis Group or ICG), Chantale Ismé, Prof. Chalmers LaRose, Lecturer at the Royal Military College of Canada, and Gédéon Jean, the Chief Executive Officer of the Centre d’analyse et de recherche en droits de l’homme (CARDH).

The Standing Committee produced a report with 11 recommendations for the Canadian government’s policy towards Haiti. In a recent podcast, Yves Engler accurately describes these recommendations as “whitewashing Canadian imperialism in Haiti.” Aidan Jonah, Editor-in-Chief of The Canada Files, concurred in an analysis, while listing the ways Canada has undermined Haitian democracy.

Segura’s presence is significant. ICG is funded by George Soros’ Open Society Foundation, which also funds the RNDDH and FOKAL, Haitian organizations that actively supported the 2004 coup. They did so largely because the coup-supporting elites – including FOKAL’s then director Michèle Duvivier Pierre-Louis – also supported implementing neoliberal policies in Haiti. In contrast, the Fanmi Lavalas’ goals were to build infrastructure, raise the minimum wage, and focus on access to basic healthcare.

Clesca’s presence at the Standing Committee is also significant. Recommendation 10 states “that the Government of Canada support[s] Haitian civil society and its leadership in finding a way out of the crisis and an appropriate democratic governance model that will benefit the people of Haiti.” In other words, the Canadian government is leaving the door open to backing a Montana-led transitional government.

Recommendation 3 states “that the Government of Canada continue to work with international partners to strengthen the capacity of the Haitian National Police Force.”

This is in line with Henry’s coalition and Montana’s leadership, both of which publicly endorse the “support the PNH” intervention framework. They simply disagree on who ought to be in power when the help arrives.

Trudeau’s reticence to lead a “multinational special military force” into Haiti may look like a rejection of foreign intervention as a solution. Trudeau, however, is simply unwilling to lead this intervention. The Standing Committee’s report relieved some of the pressure Trudeau has felt on the international stage to do so, as Recommendation 11 states that Canada should promise that “it will not participate in direct engagement in military operations on the ground in Haiti by Canadian Armed Forces.” This provided Trudeau with an easy out.

Domestic politics are a factor too. Trudeau has a minority government that is maintained by a coalition with the New Democratic Party. The NDP is officially opposed to a military intervention, stating that a “militarized approach is neither sufficient nor sustainable.” The NDP is in favor of the Montana Accord as a legitimate transitional government for Haiti.

Trudeau’s track record shows that he is more likely to engage in policies that are largely performative, such as supporting a fascist coup in Bolivia and an unelected leader in Venezuela, or presenting Canada as a safe-haven for refugees, while deporting Haitians back to Haiti by the hundreds.

Trudeau’s lack of interest in leading an international force belies a fundamental agreement on U.S. policy towards Haiti. He simply understands an intervention of Haiti is a commitment to occupy Haiti and that would likely lead to a quagmire.

His preferred framework for an intervention into and occupation of Haiti is outlined in the U.S. Global Fragility Act.

The Global Fragility Act

Canada quietly endorsed the Global Fragility Act (GFA) in early 2020. A single statement by the Canadian Embassy in the United States stated that Canada “celebrated the passage” of the GFA. The statement goes on to explain that the GFA “aligns with a number of Government of Canada development and foreign policy priorities.”

As journalist Kim Ives noted in a recent article, “although the GFA was passed with bipartisan support under Trump in 2019, it has remained under the radar.” He explains, the GFA is “essentially a new alliance of USAID ‘know-how’ with Pentagon muscle.”

Frances Z. Brown, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, views the GFA’s “bilateral agreements with fragile states” as a way to prevent China and Russia from “preying upon weak governance.”

The Biden administration released “The U.S. Strategy to Prevent Conflict and Promote Stability 10-Year Strategic Plan for Haiti” on Mar. 24, 2023, saying it had chosen Haiti for “its strategic relevance and proximity to the United States and the need for a more coordinated long-term approach to address drivers of instability in the country.”

To achieve this, the U.S. plans to “integrate U.S. diplomacy, development, and security-sector engagement in Haiti.” In other words, the State Department, its humanitarian arm, USAID, and the Pentagon will all work in close coordination.

Ives explains that “this means that the new DOS/USAID/DOD complex will effectively take over Haiti, if Washington gets its way, thereby returning the country from a neo-colony back into a virtual colony as it was from 1915 to 1934, when U.S. Marines occupied and ran it. Nonetheless, the U.S. would try to keep some Haitian window-dressing.”

Under the GFA, these “multi-year programs” are in fact ten-year “planned security assistance” programs.

In a prepared statement to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Jim Saenz, Deputy Assistant Secretary Defense for Counternarcotics and Stabilization Policy, explained that the Defense Department “will play a key role in planning and implementation” of the GFA. The “DoD’s role in GFA implementation is to support the efforts of the Department of State as the lead, and the USAID” to “ensure that the ten-year plans for the priority countries and regions align the relevant goals, objectives, plans, and benchmarks with DoD policy”, Saenz explained.

Unsurprisingly, Susan Page, the aforementioned ex-head of MINUJUSTH, endorsed the GFA, proposing in her piece for the CFR that “the United States and other partners should begin planning for multi-year development programs” with Montana leadership under the GFA.

The GFA’s broader context was explained when the act was rolled out. Frances Z. Brown, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, views the GFA’s “bilateral agreements with fragile states” as a way to prevent China and Russia from “preying upon weak governance,” reflecting the concern of many U.S. think tanks.

A successful “partnership” under the GFA between Haiti and Washington would ensure that Haiti remain under U.S. hegemony for decades. This would also block diplomacy and investment from countries like China which have, as recently as 2017, offered a $4.7 billion USD infrastructure project.

Washington is desperate to keep so-called “fragile states” like Haiti from developing diplomatic relationships with China and Russia and potentially joining in investment projects like the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, or BRICS.

Jovenel Moïse, who was assassinated two years ago, learned this lesson the hard way. Mired in corruption and increasingly isolated from Haiti’s oligarchs, Moïse established formal diplomatic relations with Moscow only one month before his assassination, accrediting Russian ambassador Sergey Melik-Bagdasarov. It was the first time Haiti had established diplomatic relations with Russia. Many argued that this could have been a factor which led Washington to green-light Moïse’s assassination.

Indeed, Washington has good reason to fear Haiti building diplomatic relations with Russia. It was common to see Haitians flying Russian flags in street protests over the past year. Haitian economist Boaz Anglade explains that Haitians see that “Putin has defied the West through the invasion of Ukraine and smell the advent of a new world order where no one country will be calling the shots.” In other words, a multipolar world may work in favor of Haitians. According to Anglade, “Haitians have been paying attention to global events and are sending a clear signal to the United States.”

This dynamic speaks directly to the class divide in Haiti. While sectors of Haiti’s bourgeoisie compete for approval, support, and funding from Washington, the Haitian lumpen proletariat and peasantry want to rid themselves of U.S. hegemonic rule. Haitians see the economic and social benefits of investments and trade deals with countries like Russia, China, and the BRICS generally.

Indeed, in a recent poll of Haitians, when asked who they would prefer to lead an intervention into Haiti, 44% of 2610 responses preferred Russia, compared to the United States at 19%. Canada’s favorability had dropped from 23% to 12%.

This is why Washington and the CORE group conspire to keep Haiti strait jacketed under U.S. hegemonic rule.

Manufacturing consent for the Global Fragility Act

Washington has been manufacturing consent through various National Endowment For Democracy (NED), USAID, and Open Society Foundation supported groups to nurture support for the GFA. NED-funded organizations such as Initiative de la Société Civile and OCAPH have endorsed the GFA.

Nou Pap Domi is a foundational member-organization of the Montana Accord coalition. One of its foremost members and spokespersons, Emmanuela Douyon, recently offered support for the GFA at a Dec. 15, 2022, Alliance for Peacebuilding conference.

Douyon previously worked for the National Democratic Institute (NDI), an arm of the NED, which in turn is funded by the U.S. State Department and USAID. Later, she received an NED grant to found Policité, a “think tank” that conducts surveys and offers consultation services.

Jeffsky Poincy, another analyst who spoke at the conference, said that he was “glad Haiti is part of the GFA.” Poincy is a program manager at Partners Global, a consultancy firm funded by the U.S. State Department, the Canadian government, the Open Society Foundation, and USAID.

Naed Jasmin Desiré is another example of a leader of a U.S.-funded organization that backs U.S. foreign policy in Haiti. Desiré co-founded Kafou Lespwa (KL) with multi-millionaire Haitian investor Charles Clermont. According to a USAID report, Kafou Lespwa used USAID funds to launch KL, which relies on NED funding for annual operations. Kafou Lespwa brings together disparate sectors of Haiti’s political class to build a consensus on how to “emerge from the current crisis.”

Among the Haitian elites, politicians, and leaders on the Kafou Lespwa “team” are: Clifford Apaid, the son of oligarch Andy Apaid who led the Group of 184 organization; Abdonel Doudou, an NED fellow and head of Jurimedia in Haiti; Edgar Leblanc Fils, OPL’s general coordinator; Fritz Alphonse Jean, the Montana Accord’s proposed interim President; Joel “Pasha” Vorbe, who sits on the FL’s executive council; Liné Balthazar, the PHTK’s President; Pascales Solanges of Nou Pap Domi, and Paul Altidor, the former Haitian ambassador to the U.S..

A lawyer by trade, Desiré was also involved early on in the coalition behind the Montana Accord, eventually becoming a member of the BSA, led by Magalie Comeau Denis and Ted Saint Dic. Desiré eventually became the CNT Secretary.

While Desiré’s view on the GFA is unknown, her KL co-founder Charles Claremont endorsed the GFA when he spoke at a NED conference in July 2022.

Montana’s leaders have yet to publicly endorse the GFA. Their modus operandi – seeking support and approval from Washington while eschewing building diplomatic relationships with other governments, regional organizations, or international organizations – suggests they will eventually announce this support, likely when Montana takes over, or is integrated into, a transitional government.

Haitian political party speaks out against Global Fragility Act

Meanwhile, political parties inside Haiti are sounding the alarm on the GFA. OPL general coordinator Edgar LeBlanc Fils, a Montana Accord front-runner for the position of interim President, worries that de facto PM Ariel Henry will try to negotiate “security assistance” from the U.S. under the GFA.

The OPL is one of many political parties that initially supported the Montana Accord. Whether or not they maintain that support is unclear. The OPL is a signatory to the Accord. But recently, the party signed a declaration with seven other political parties, including UNIR, LAPEH, GREH, PHTK, MOPOD, and Platfòm Pitit Desalin. Most of the parties are listed as members of Montana’s CNT, including the PHTK. Their desire to publish a declaration on Jan. 30, 2023, separate from Montana, suggests waning support.

The declaration states that the signatories “renew their commitment to favor the higher interests of the country over personal or particular interests and ambitions linked to the conquest and exercise of power.” While opposition to Henry’s December 21 Accord is stated directly by signatories, support for Montana is absent from the declaration.

PHTK President Liné Balthazar actually distanced himself from Henry months ago. It is unclear whether this is simply political maneuvering or authentic opposition to Henry’s de facto rule. The PHTK’s joint-declaration with left-of-center political parties like Pitit Desalin and MOPOD is noteworthy.

An Apr. 24, 2023 open letter to the UN Security Council President signed by several political party and civil society organizations also called out the threat of the GFA. Signatories include the leaders Oxygène David of MOLEGHAF and Jean Hénold Buteau of Alternative Socialiste. Referring to the GFA, the letter asked the Security Council president, Russia’s Vasily Nebenzya (the position of President of the Security council rotates monthly between 15 member countries), whether the United States’ policy to “impose a ten-year plan” on Haiti, which is a “violation of the right to self-determination of the Haitian people” ought to be raised.

Political parties have reshuffled their alliances several times since Jovenel Moïse refused to step down at the end of his term on Feb. 7, 2021. Their lack of success is due in part to the political class’ inability to build solidarity with the population and mobilize Haitians.

Haitians are clearly unwilling to wait for the political class to defend them from the endemic, depraved violence of armed criminal gangs and the politicians and oligarchs who support them. Since late April, tens of thousands of Haitians have coalesced into a leaderless nationwide movement called the “Bwa Kale” which has pursued, confronted, apprehended, and killed over 100 criminal gang members.

(Part 3)

An earlier version of this article was first published by The Canada Files. Travis Ross is a teacher based in Montreal, Québec. He is also the co-editor of the Canada-Haiti Information Project at canada-haiti.ca . Travis has written for Haiti Liberté, Black Agenda Report, TruthOut, and rabble.ca. He can be reached on Twitter.