New York-Schooled

Exactly when and the extent to which Merisier began to understand the role of DeWitt Peters or Selden Rodman is debatable. But he must have started to sense a certain correspondence between the politics of New York City’s art world and the Centre-Foyer dynamic at least since 1969. This was when he participated in a small mostly Sophistiqué show at The Brooklyn Museum Community Gallery. (This gallery was merely a roomy, but somewhat sequestered hallway space that led to the museum’s cafeteria and that condescending museum officials, under pressure from African American cultural activists in their struggle for power and against racism and exclusion, conceded in 1968. As if it could marginalize further the art that community leaders would choose to display in the Community Gallery, the museum’s leadership back then formally stated that its curators would have nothing to do with the choice of art exhibited in the set-aside space.)

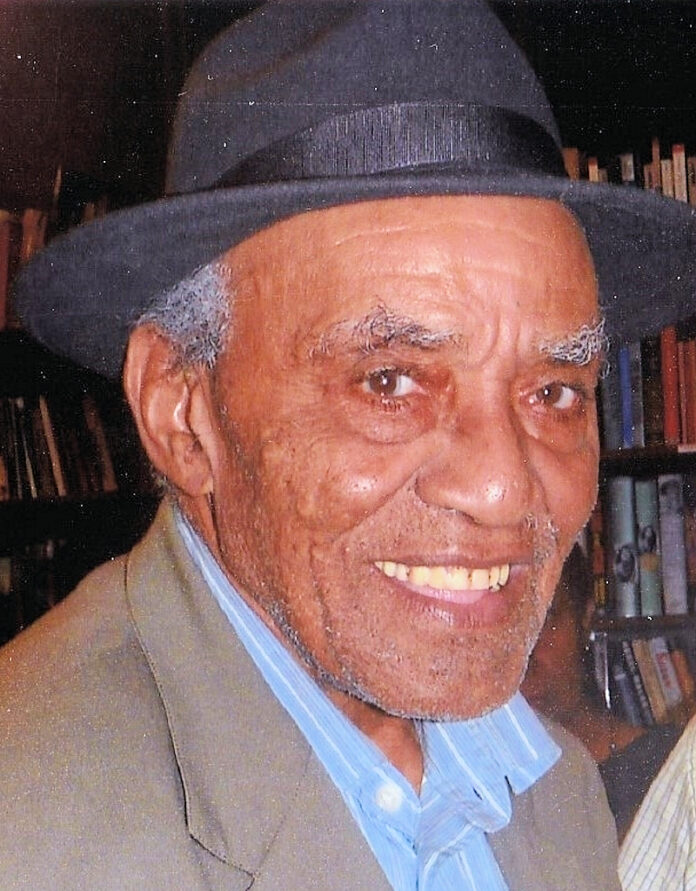

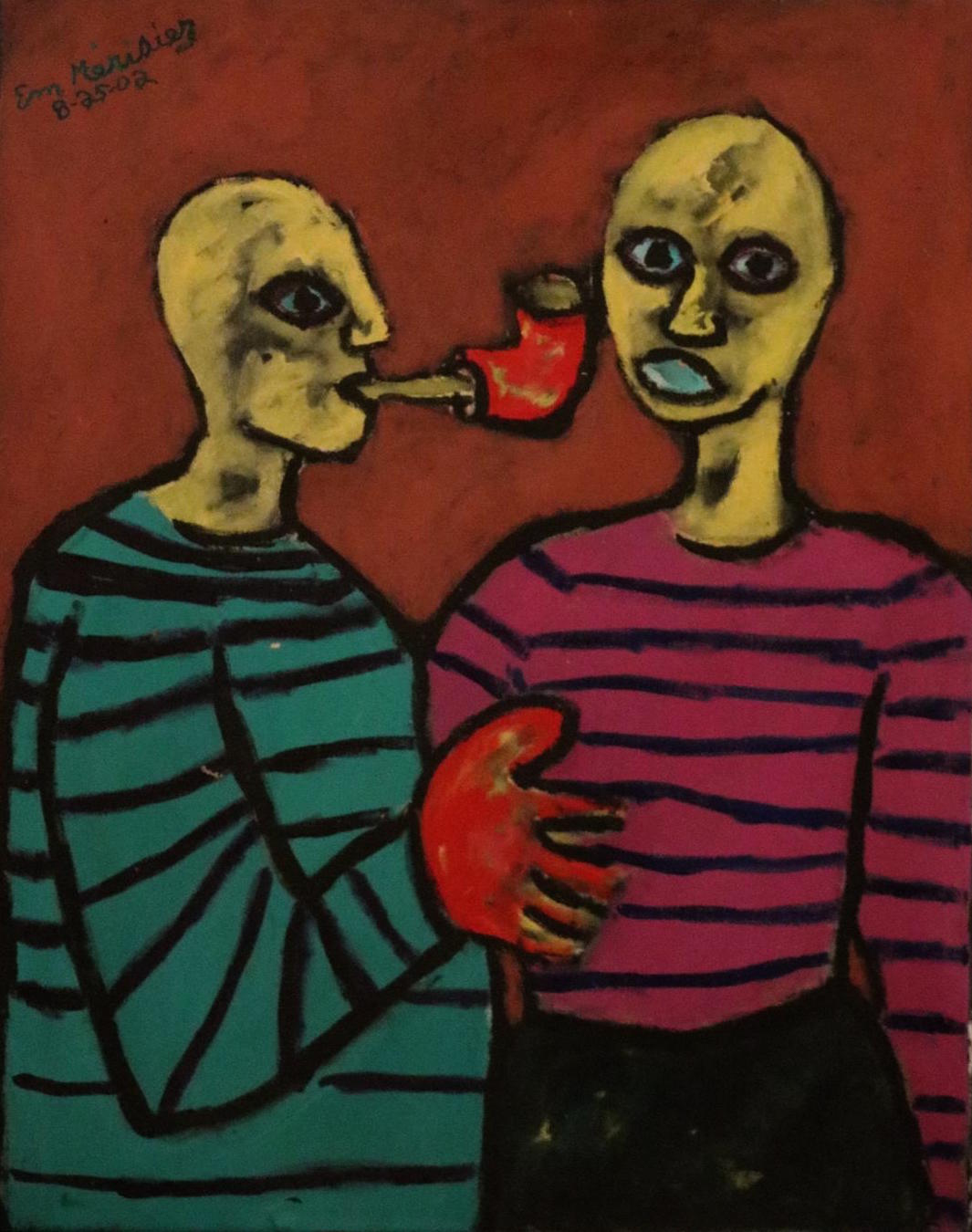

Apparently, the Museum of Natural History would tacitly follow a similar practice, as when about seven Haitian artists, including Raphael Denis and Jean Dominique Volcy, participated in 2004 in a one-day “ethnic” group show in a hallway near its permanent displays. (Volcy insisted that the paintings to be shown not be displayed on tables, as the museum’s liaison originally planned.) More importantly, the Queens Museum (or its public or community relations arm), where Lerebours and the socio-culturally influential artist Jean-Claude Garoute (Ti Ga) were honored on separate occasions, would also assume the same posture. In Ti Ga’s memorial, backed up by an informal or pick-up Haitian art show that museum curators apparently had nothing to do with, I recall Merisier gloatingly introducing to me with a wide grin on his face the exceedingly wild painting he himself had chosen to contribute to the event, as if to goad viewers: his 2002 “Nègre feuille.”

But if he was most likely not aware of the Brooklyn Museum’s racist maneuverings or, later on, simply unconcerned about the Queens Museum ghettoizing him and his compatriots, Merisier might have noticed that, according to Lerebours’ entries for each of the 15 artists in the Community Gallery show as well as the average listed prices for their works, he was at the very bottom of the pecking order since back in 1969. For instance, unlike Depas, Lazard and others, Merisier had not sojourned in Europe’s metropolises, with their great museums and cosmopolitan charms, and his art education was relatively thin, summarized in just one line about him attending the Foyer. By 1977, when he was excluded from a second similar show at the same Community Gallery, he must have begun seriously to question the course of his art career.

Indeed, the 1977 show was a ploy that must have blinded the local Sophistiqués to the fact that the Brooklyn Museum was in the process of preparing what was slated to open a mere nine months later in 1978 – in its main formal galleries, no less – what would then be the biggest or, probably, the most produced Haitian art show ever. (Depas, who was actually part of the governing body that oversaw the Community Gallery, once mused to me about his desire to show his work in the museum’s main galleries.) It was a triumph of sorts for the Foreign Haitian Art Establishment. For Rodman’s stamp was all over the show. Of the 53 artists presented, none of them was actually a Sophistiqué, although most of the Foyer artists were still active. (Three token modern artists living in Haiti were included: Bernard Séjourné and Jean-René Jérôme, School of Beauty painters who tend to romanticize or sensuously embellish with flowing lines imagined or cherry-picked local themes, and Valcin II, an artist of somewhat similar ilk, despite his political themes.)

At last, on some level, Merisier must have discerned the writing on the wall. He would continue to show his work wherever and whenever he could. Most of all, he would bide his time. He would attend the School of Visual Arts’ Division of Continuing Education after his daytime construction job, maintaining links with Haitian art dealers such as Gloria Frank and Léon Cholom and, as usual, visiting museums and galleries. (I ran into Merisier at the Guggenheim Museum’s 1980 exhibition “Expressionism: A German Intuition.”) Of course, he continued to visit the homes of his Foyer peers, taking in the often heated, booze-soaked art conversations and anti-Duvalier discussions. New York was then, before the advent of multiculturalism and neoexpressionism, still partly in the critical fold of minimalism and pop art and, thus, a dead end for the Sophistiqués. It’s apparently with mostly hindsight, when the career of his peers had seemingly plateaued, that Merisier, as if on more secure, more propitious turf, would impugn their capacity to carry out their program in the early Foyer years. Perhaps partly because of their various travels and their earliest open studio presentations and shows abroad and, especially, back in Haiti (with the resulting fact that, to this day, tourists there often take their purchased works with them – even during the course of an exhibition), the Sophistiqués, not unlike the Primitifs, had difficulties documenting or fully accounting for the trajectory of their development. But Merisier, who arranged for much of his work to be documented and sold some of it to just a few collectors in the New York/New Jersey area, would cite his peers’ relative lack of serious art experience in general – even with their sojourns in important art capitals: “Nan ki ben [atistik] yo te ye?” he would throw out. (“What significant art milieu were they really integrated in?”)

Merisier might have noticed that he was at the very bottom of the pecking order since back in 1969.

For instance, in one of the longer entries on high-profile individual Sophistiqués in Haiti et ses peintres, Lerebours drops the names of some famous artists that Lazard himself apparently told him he met in Paris in 1950 and in Mexico in 1956. But Lerebours provides no elaboration or concrete details about such encounters beyond, for instance, that Diego Rivera and Rufino Tamayo had “received” Lazard in Mexico or that “Chez Fernand Léger,” to whose place the writer Michel Leiris had introduced him, Lazard encountered Siqueiros who, “about to leave to Poland” (we’re needlessly apprised), conveyed his “aesthetic beliefs” to the 22- year-old artist.

Nevertheless, Merisier never talked much about Gallery Brochette, an exhibition space and meeting ground for many Sophistiqués and intellectuals that Roland Dorcély, Lazard, and Cédor, among others, launched in 1956 in the wake of a disintegrating Foyer. Among the 14 artists listed as being regulars at Brochette, Lerebours cites Merisier’s name, his only mention in Haiti et ses peintres, a rampantly comprehensive two-volume work. (As seen, Lerebours finally includes an early painting of Merisier in his Bref regard sur deux siècles de peinture haitienne, a very abbreviated and updated version of Haiti et ses peintres.)

Merisier also pointed out the fact that back then in Haiti, aside from the limited information one could draw from mere reproductions in books and magazines (and, one could add, even from a smattering of modern Cuban works exhibited in Port-au-Prince at about mid-century), virtually no actual models of the modern European art to be apprehended and emulated were available. Clearly, Merisier gradually realized that he was in a better position to strike out toward greater artistic heights than his peers had been capable of, even in their early days in New York. It’s no wonder, then, for his 1982 show he billed himself in the Art in America ad as well as in his invitation cards as Haiti’s “leading contemporary artist.”

As true as Merisier’s charges may be, and in fairness to the Foyer pioneers, theirs was tall order. They had scant local support at first. Tourist dollars and publicity was bestowed on the leading Primitifs at the Centre by its art-propaganda juggernaut, in the form of mostly Selden Rodman but also, among other (French) intellectuals, André Breton, and more recently, American film director Jonathan Demme. Although there have been some apparently modest Sophistiqué solo shows in Haiti over the years (judging just by a few underproduced catalogs), to my knowledge there have been no serious or probing exhibitions focusing on the artists’ earliest works or on their evolution as a group. Indeed, the modern art establishment is as much about artistic excellence backed up by pertinent critical discourse as it is about commodification and the juncture of national and international capital and power. (The art of the leading primitifs had some of this going for it, and it somewhat mirrored on a much smaller scale the post-World War II art boom in the United States.) Obviously, the more a given community or nation does not exercise its power and independence sufficiently, the more its resources – including human and artistic – will be neglected or exploited. Surely, it’s in the mirrors that all the arts together represent that a nation sees, reinvents, and asserts itself.

But Haiti and its dependent ruling class has done a poor job in “safeguarding” and “valuing” the “expression of her people,” to quote from Eleanor Christensen’s “The Art of Haiti.” For instance, the artistic precedents that might have helped Foyer leaders steer the course were by mid-century seemingly scattered, unaccounted for, or simply buried in art-historical memory – or, arguably, in plain sight. These included the figurative sculptures of the well trained Normil Charles (1871–1938), the small, but prescient historical portraits of Édouard Goldman (1870–1930), the plein-air works of the African American William Scott (1884-1964) who in just one exhibition in Haiti in 1931 had sold 27 paintings – and much more, including Pétion Savain’s early works. There was also the visual wealth to be found in Vodou, popular culture, and the country’s various crafts. Indeed, the very modest Musée D’Art Haitien du Collège St. Pierre, the country’s first art museum, would not be built until 1972. Thus, if in fact an inventory of art that’s available locally supersedes the need for external outreach or research in secondary sources, then the original Foyer artists’ idea of seeking the “light” of modern art in imported books or outside of the country was also somewhat hollow and unfortunate.

Breaking the Haitian Art Mold

More importantly, since theoretically among modern art’s hallmarks are its oppositional, autonomous, and original aspects, in retrospect, it was best to build on, or against, what was locally produced. Impugning the lures of mainstream modernism’s would-be universalist precepts, for instance, would almost automatically yield an art that’s oppositional, autonomous, and original – hence, modern. This is to a great extent what the original leading Primitifs did, whether consciously or not, despite many of them at first being given at least some rudimentary training in the western art tradition (as drawing from models) or were plied with brush, paint, and board/canvas – art-historically neutral materials but, as seen, in the hands of Hyppolite, also potentially modern. This is also what the maverick painter Dorcély, apparently did, extrapolating from a few of his rare reproductions and, especially, from the 2019 Frieze Art Fair in New York, where 14 of his compelling Primitif-inflected figurative works and landscapes (done in Paris around 1958) were exhibited.

The same could be said for the convincing early paintings of, among others, Pinchinat (before his art seemingly devolved into what comes across – in reproductions – as a facile type of cubism) and, potentially, for some of the figurative and abstract efforts of Lucien Price. Thus, Merisier’s critique of the Foyer Sophistiqués is unfairly overstated. Were the Local Haitian Art Establishment to have probed and showcased their efforts – especially in the earliest phases of their careers – in scholarly, well-documented exhibitions, it’s likely that we would witness an astonishing endeavor in modern art history.

Still, the hollow but socio-politically serviceable dichotomy between Primitif and Sophistiqué was long shattered by both camps in the Centre-Foyer dynamic, not least, also, by Luce Turnier in her earliest portraits. (She and a few other artists of modernist sensibility, including Antonio Joseph, had never separated themselves from the Centre, even if not necessarily for strictly art-theoretical or philosophical reasons.) In fact, it’s been evident that as early as during the U.S. Occupation of Haiti, the artist Édouard Goldman had already harmonized in his small, would-be portraits of eminent Haitian leaders and personalities both the can-do aesthetic approach of the Primitifs and the middlebrow, sensuous romance that generally characterizes the School of Beauty – the suave, local offshoot of the Sophistiqués.

For example, Goldman’s profile of Toussaint Louverture (copied from a familiar engraving) is not so much a portrait in the traditional sense. Rather, it’s as if in his performative approach he were playing dress-up: using as if a template-like cardboard effigy of Toussaint, he covers it up in Primitif garb (note the tap tap-like patterns and coloring on the figure’s torso and plumed hat). Instead of actually painting and rendering Toussaint’s face, he seems merely to have colorized it, ending up with a captioned, sanitized image that one could take for a staged civic lesson – so casual and preciously earnest it looks. Merisier’s approach to his art, in his appropriation of mainstream modernist as well as Primitif tropes – or, in other words, in his overall disregard for the idea of originality – is quite similar to Goldman’s, but with visceral oomph, instead of wholesomeness.

Generally, an ostensibly modern work created by one who asserts his or her Haitian-ness in the context of the Centre-Foyer dynamic must necessarily contain local or Primitif inflections. The obverse of this is also true: the deliberately Primitif-looking works of Merisier, who also asserts his allegiance to modern art, must also be inflected by modernist concerns. Besides, numerous contemporary Haitian artists who are worth their salt, ranging from Télémaque to the late Paul Gardère and Tessa Mars, often foreground Primitif art in their work. And it’s also likely that Peters, Rodman, and Bréton – all of whom suckled by modern literature or modernism in general – were able to apprehend the viability of Primitif art simply because its inherently modern aspects appealed to the schemas in their aesthetic memory. So, in a sense, they themselves could have superseded the Primitif-modern dichotomy and thereby contributed to the Haitian art scene’s more constructive and dynamic integration and, to that extent, loosen the country’s social stratification.

Of course, art communities and ruling classes must independently and at their own pace do this for themselves. But Rodman, and others who took their cues about Haitian art from him, piggy-backed on the very conditions that made the efflorescence of the Centre possible. He rode out the indigenist wave, the mostly bourgeois literary and cultural movement that was underway even before the 1928 publication of Jean Price Mars “Ainsi parla l’oncle,” and in the process, further polarized the mostly Francophile elite and the Vodou-inspired masses. Wielding expediently the idea – and not the actual historical ties of – “African Haiti,” as if to build critical support for Primitif art – which, as Lerebours points out in Haiti et ses peintres, Rodman at one point was actually selling and profiting from in his New York City gallery – he outmaneuvered the staid elite by thwarting the potential leadership role and critical discourse that could have ensued from its small, politically, and culturally progressive wing. For instance, though upper class figures such as Philippe Thoby-Marcelin, who was exiled in 1948 for his political activities, and Jacques Stephen Alexis, who was killed in 1961, did manage to add their voices to the critical discourse on Haitian art, socially and politically ambitious working class artists such as Dieudonné Cédor never quite managed to contribute their share.

Merisier hardly appreciated the dynamic of this double-edged sword wielded by the Foreign Haitian Art Establishment.

In short, Rodman and the Centre ultimately stymied the upward social mobility of the working-class Primitifs, whom they indirectly supported and encouraged so as to better control and leverage them as a mere art and cultural resource and, simultaneously, to keep the local (progressive) elite and its working class allies off-kilter and at arm’s length from this resource. So, as much as Rodman championed the leading Primitif artists, his paternalization and exploitation of them, together with his contempt for and condescension toward the local elite, commensurately stunted the growth of the potentially bourgeois and modernist clout of the Primitifs, who in great part were the offsprings of the “African Haiti” he pretended to sympathize with.

It’s clear that Merisier hardly appreciated the dynamic of this double-edged sword wielded by the Foreign Haitian Art Establishment. Or he simply turned a blind eye to it: “M ap pran kout baton nan men blan, men m pap pran l nan men nèg!” he more than once said. (“I may be beaten by the white man, but I won’t accept the same from a black man.”) Perhaps it was this logic, which itself, in its subtle semantic nuances, also smacks of a degree of self-hate as well as a will to rebel against the bourgeois pretensions of his compatriots, that impelled him to append in back of the invitation card for his 1982 show, “This exhibit is dedicated to the people of the United States” – not to his gwo pèp.

It follows, then, that he would tend to discount the Local Haitian Art Establishment, as represented to a great extent by Lerebours and others, such as Gérald Alexis. They generally aver the Sophistiqués’ goal of using Primitif art as a mere stepping stone to greater, more art-historically pedigreed heights. But, incredibly, that’s in great part what Merisier did, not just by dressing up primitif themes in the garbs of early European modernism, but ultimately by instrumentalizing the Primitif against the supposed universality of modern art itself. He produced his deliberately crude pictures of ungainly, disproportionate figures – the breakthrough paintings – around the period when he was also (needlessly) attending The Art Students League for classes in figure drawing in which, his sketch pads show, he was moderately competent. (Evidently, Merisier is much attracted to artsy ambiences, but guardedly so.) As an avowed Primitif Modèn – neither a Primitif nor a modernist in the molds of the original Centre d’Art and Foyer artists – he was too much a wayward maverick to attract the support of the Local Haitian Art Establishment, much less to be credited for fulfilling the original goals of the Foyer Sophistiqués. More importantly, because Merisier discounted the art of the Sophistiqués and never acknowledged that of the Primitifs as being really modern, he by default would end up in the fold of the Foreign Haitian Art Establishment.

To be continued