What happens in Haiti doesn’t stay in Haiti. Sooner or later, it comes to places like Michigan’s Benton Harbor and Flint. Our destinies are linked.

Zbigniew Brzezinski, a Polish aristocrat who long puppeteered United States presidents from behind the curtains, has written: “America is too democratic at home to be autocratic abroad. This limits the use of America’s power, especially its capacity for military intimidation.” I concur. As long as the U.S. attempts to dominate the world and continues to dispense the violence commensurate with this ambition, it cannot expect to practice democracy at home.

Mr. Brzezinski reasoned that the main impediment to imperial ambitions is that people will not be willing to get killed in wars of conquest, but I believe there are more profound reasons why democracy cannot thrive under such circumstances. For one, the servants of empire develop a comfort with dictatorship that eventually compels them to cross the Rubicon, as they did in Roman times, and come home to continue the practice. Even more important, democracy cannot flourish where the rich are free to justify their money accumulation by rendering everyone and everything salable. A symptom of such pathology is the phenomenon of privatization.

Triple whammy

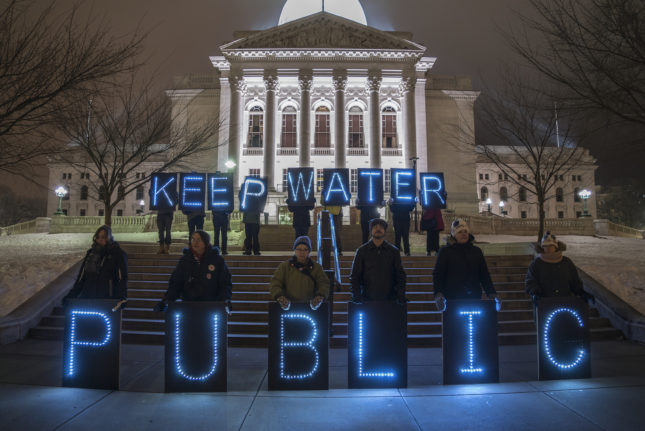

The battle has begun to privatize the functions of city governments, which really hold the commons and real wealth of any country. Water is at the center of this battle, and this includes waterfront property as well as drinking water. In Haiti, immediately after the earthquake of Jan. 12, 2010, Bill Clinton pressured the government to declare an 18-month state of emergency, during which he could govern all the reconstruction as the co-chair of the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC). There is little to show for more than $6 billion of aid funds to the IHRC besides a massive sweatshop complex, built for less than 3% of that amount, well away from the earthquake damage. Haiti’s mayors, the main impediments to the appropriation of land and water commons, were dismissed and replaced with Interim Agents appointed by a president who, in turn, had been installed by Hillary Clinton in May 2011 in a fraudulent election.

In Michigan, there was no earthquake as there had been in Haiti. Instead, the disaster was slow and cumulative. Though Clinton is credited for most of it, it had the approval of Republicans and Democrats.

First came the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) of January 1994, which eliminated tariffs and other trade barriers between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. Corporations like Whirlpool and General Motors moved their production to Mexico and abandoned those who had made their livelihoods for generations as predominantly unionized laborers.

The housing crash in 2008, due to the banking sector’s financial crimes, caused a rash of foreclosures. Finally, as more people fell into poverty, the federal government unraveled most social safety nets, including welfare and food stamps. The old manufacturing cities lost much of their population, together with their tax base. The residents who stayed, however, retained their power to vote despite being poor. Against this, the scions of corporate bosses, big property owners with plans of their own, continued to influence politics at the federal, state, and city levels. A clash between the poor and the rich of these cities became inevitable.

Ground zero, Benton Harbor

It is in Benton Harbor, a town of about 10,000 people on Lake Michigan, with 70% unemployment and a per-capita annual income of about $10,000, that the fight for America’s cities started. Whirlpool Corporation was the major employer and had its corporate offices there, when a plan was hatched to take 530 acres of the city, including a lakefront park, for conversion into a $500 million development called Harbor Shores, with multi-million dollar condos on the beach area and a Jack Nicklaus Signature Golf Course. In response, Reverend Edward Pinkney, a pastor and community leader, spearheaded the organization of the local 2008 elections and the recall of a mayor who had borrowed $3.2 million for the city, rather than require Whirlpool to pay its fair share of taxes. Opposition candidates won four commissioners seats and the mayoral seat: the five votes that were needed to control the City Commission.

Whirlpool got $3.87 million in tax breaks in 2010 and left Benton Harbor for Mexico in March 2011, but the corporate bosses’ influence remained. Soon thereafter, the state of Michigan declared Benton Harbor to be $5 million in debt and then orchestrated a land grab with Public Act 4: a new law that allowed the state government to appoint, for a city, an Emergency Manager (EM) that trumps all elected local officials.

According to Reverend Pinkney, Michigan governor Rick Snyder was beholden to Whirlpool, and Benton Harbor’s first EM, Joseph Harris, was a professional accountant close to Cornerstone Alliance, which is part of Whirlpool. The city’s water bills tripled and its jobs were outsourced, but Benton Harbor paid millions of dollars to demolish the houses of its poorer residents and got its golf course and lakefront condos for the rich. Reverend Pinkney was thrown in prison for up to 10 years on a bogus charge of tampering with the mayor-recall petition.

The fight for Flint

The rich of Michigan realized right away they had good thing in Public Act 4. The state began, almost immediately, to train hundreds of EMs for appointment to other cities. Governor Snyder ordered the city of Flint into receivership, also in 2011, and the state appointed an EM for it. With the departure of much of General Motors, which had begun there in 1908, the city had lost much of its tax base and had a budget deficit. Specifically, Flint went from about 200,000 people in the 1960s to about one half this number by 2011, when the median household income was around $25,000, and about 40% of the residents lived below the poverty line.

On Apr. 25, 2014, by order of its EM, Flint began to get its water from the Flint River using a formerly retired plant, instead of the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD), which had provided the city with treated water originating from Lake Huron. The reason for this decision is often given as a need to save money, but according to journalist Steve Neavling, in response to the potential loss of a major client, the DWSD made a number of proposals to Flint, including the offer of a deal that would have been 20% less expensive than switching. In fact, the DWSD suggested that there was a political aim to the switch. One possible such objective might have been to destabilize Detroit, in a domino effect, for the assignment of its own EM.

The story of Flint’s water contamination is no less tragic for being told many times. The corrosive water from the Flint River dislodged the protective scales from within the service water pipes and caused so much leaching of lead, that in some instances the water contained lead concentrations that would have been considered high even for toxic wastes! This happened because when residents complained about the brown coloration of the water, and later of infections with pathogenic Escherichia coli, the city hired two water-privatization companies, Veolia, and Lockwood, Andrews & Newman (LAN), to solve the problem. To save money, anticorrosives were not added to the water. The discoloration was treated by Veolia, which then declared the water safe to drink. Chlorination of the water in an attempt to disinfect it led to yet more leaching of lead. In addition the chlorine was removed by reactions with particles of iron in the water, and this led to growth of Legionella bacteria.

In the end, thousands of people were poisoned with lead, including 9,000 children under the age of six, and 12 people died from Legionnaire’s Disease. All these facts about Flint’s water became public, not because of government watchdogs, but because of the efforts of citizen scientists who got assistance from scientists to analyze the lead concentrations in water and the blood of Flint’s children.

Two former Flint EMs, Darnell Earley and Gerald Ambrose, as well as several Flint Department of Public Works employees, face criminal charges for their roles in the Flint debacle. In addition, Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette has filed a civil lawsuit in which Veolia and LAN are both alleged to have committed professional negligence and public nuisance, and Veolia is also alleged to have committed fraud. The city draws its water again from DWSD, but the damaged pipes continue to leach lead and, like Haitians who have come to depend on tanker-truck water for their food and drink, Flint residents subsist on bottled water.

Emergency Managers: a rich man’s antidote to local democracy

Michigan voters repealed Public Act 4 in 2012, which had disenfranchised the majority of the Michigan poor, who are overwhelmingly black, but the same year, the state passed Public Act 436, and this has been upheld after a court challenge. A fact sheet from Michigan State University Extension summarizes the law as follows:

“If an EM is appointed, this person is authorized to act for and in place of the local governing body and administrative officer of the community. The governing body only retains any powers authorized by the EM. The EM has broad powers to resolve the financial crisis and insure the fiscal accountability of the community to provide services for the health, safety and welfare of its residents.”

Like Bill Clinton in Haiti’s IHRC, EMs are appointed for 18 months with a possibility for indefinite renewal. Public Act 436 is a law that extracts all meaning from the word democracy and spits it out like so much trash onto a garbage heap. Nevertheless, many U.S. cities are trying to pass similar laws. In effect, the EM law says that you can only have what you’ve got so long as somebody rich and powerful doesn’t want it.

In a context of privatization, where everything can be bought and sold, groundwater, glacier water, rivers, and lakes may be sold, as can roads, bridges, parks, state houses, and museum artifacts. The rich, who would corral the sun and sky and put a meter on them if they could, are not treated as the threat they really are. Much lip service is given to the idea of water being a human right; if this repeated enough times, it will become another platitude. But life is not worth living if there is nothing one would die for. What is a human right but a right without which one would not be fully human, and life would not be worth living?

This is the third article of a series that examines how water is snatched from cities and privatized. Find Part I and Part II here. The original version of this article was published in News Junkie Post.