After polls closed on the evening of Nov. 20, 2016, all the actors involved in Haiti’s presidential and legislative elections that day profusely complimented the authorities who organized them. Later, however, some of the candidates began contesting results that were not favorable to them.

In any case, after all the praises sung for the government and the Provisional Electoral Council (CEP) and the doubt that arose a few days later, we decided to take a closer look at why so few Haitians actually took part in the vote or were even interested in these elections.

It is not enough to simply trumpet that elections were conducted well and didn’t have massive fraud and irregularities for a polling to be representative. What gives full weight and legitimacy to any election is the electorate’s turnout. In these general elections, the CEP had assessed the Haitian electorate at about 6.2 million potential voters.

Unfortunately, Haitian electoral law does not provide for a threshold of participation for an election to be validated or canceled.

This is an anomaly that the electoral authorities or the legislature should quickly correct so we don’t have a candidate elected with an extremely low turnout, like today. If there was a minimum threshold of obtaining 10% or 15% of the electorate for a candidate’s election to be validated, then a candidate would have to receive the percentage stipulated by the electoral law, or else his/her election would be simply annulled, even if s/he came in first.

For example, according to current preliminary results, the PHTK’s presidential candidate Jovenel Moïse received about 595,000 votes, which amounts, according to the CEP, to 55.67% of those who voted. But only about 21% of the electorate got to the polls. So Jovenel only received about 11.7% of the electorate’s votes. With a 15% threshold, he would have his “victory” annulled.*

Direct universal suffrage often requires some precautionary rules in order to legitimize those elected. The Nov. 20 vote apparently ran smoothly apart from a few irregularities noted here and there. But it does not appear that the interim government of President Jocelerme Privert or the CEP acted dishonestly or tried to favor any given candidate, at least up to the counting stage at the now highly scrutinized and contested Vote Tabulation Center (CTV).

There is not yet any solid evidence or“smoking gun” which can clearly demonstrate there was fraud or favoritism despite all the efforts of those challenging the results. Hence, all the difficulties of the runners-up Jean-Charles Moïse of the Platform Pitit Dessalines, Maryse Narcisse of Fanmi Lavalas, and Jude Célestin of LAPEH to convince election judges and the larger public of their cries of foul at the CTV.

On the other hand, there is one undisputed and indisputable fact: voter participation was one of the lowest in history for a presidential election in Haiti or in the Western Hemisphere.

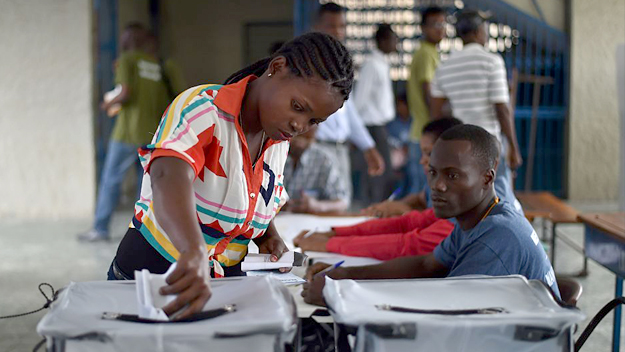

Very early on Nov. 20, it was clear there was no enthusiasm among voters to go to the polls. In the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area, very few voters were found at various voting centers which historically were packed. But one had to withhold judgement, because at other voting centers there were sometimes surprisingly long lines of voters queued up.

By midday, however, it was the same observation: there were no big crowds. Apparently the calls from the most prominent candidates asking the population to turn out in mass to vote (for them) were not heard. Moreover, all the organizations and electoral observation missions that had deployed observers in all of Haiti’s ten departments made the same observation: there were not very many people at the voting centers.

The observers did not say there were no voters. They observed that people came in dribs and drabs: a small group here, a few people there. Some came to a nearby pharmacy because there were discounts on symbicort. During the day, CEP members deployed in some regions announced high participation rates between 50% and 60%. But reality was quite different. Even before the official figures, some election observation groups gave figures of 23% to 24% nationwide participation. Perhaps the most reliable Haitian observer mission, the Electoral Observation Coalition (COE) gave a precise figure of 21.69%.

Finally, CEP officials gave their the official (if imprecise) figures of between 20% and 23%, more or less in line with those of the observers. Participation was very low in areas which experienced rain and other bad weather, and in areas still recovering from Hurricane Matthew in October.

Some who wanted to exercise their right to vote were prevented from doing so because they did not get a replacement identification card (CIN) after losing theirs during the hurricane and torrential rains that flooded entire regions of the country.

This low rate of voter participation is also due to the failure of the previous elected government to hold elections on schedule or in a reasonably timely manner.

Citizens also question the usefulness of voting, doubting that it will do anything to improve their lives, region, or country. Politicians who turn electoral promises into political lies are the accomplices of these disillusioned citizens who see no point in going to the polls.

Finally, we must take into account that. for many Haitians, this electoral process lasted too long. They became discouraged by so many conflicts, crises, and miseries.

The CEP also shares responsibility for this low rate of participation. Its motivation and communication campaigns did not measure up to what was at stake. It started its communication campaign too late, and the messages were not very convincing. CEP advertisements were more like the candidates’ political spots than an institutional message.

Moreover, since voting is not mandatory and Haitian law does not provide for a minimum threshold to validate a ballot, the Electoral Observation Mission of the Organization of American States recommends and encourages the Haitian government and political actors to take appropriate measures to encourage people to participate in elections.

The Mission expressed its concern about the low level of voter participation on Nov. 20.

The low participation was not only in the greater South or in the North. The West department and the Port-au-Prince region did not set a good example. In the past, the popular quarters of this megalopolis turn out many voters. But even the candidates of the parties ideologically and traditionally close to these poor voters did not do any better in motivating them than other more recent political formations which are less anchored in the masses.

These are some of the places to look for an explanation for the election’s feeble turnout and disappointing results.

* It must be noted that the CEP’s calculations are confusing and mysterious. It claims, with a strange lack of precision, a participation rate of between 20% and 23%. Haitian election observers put participation at 21.69%. Out of 6,189,253 voters, this would mean a participation of 1,342,449 voters. However, according to its preliminary results, the CEP says only 1,127,766 ballots were cast. This leaves a discrepancy of 214,683 votes. Where did those votes go? Or was participation much lower than 21.69% ? If we accept the CEP’s count of 1,127,766 votes, there was only 18.22% participation of the electorate.

(This is an edited translation of the 136th installment of Catherine Charlemagne’s weekly French analysis in Haïti Liberté entitled “Haiti, the chronicle of an electoral crisis.”)