The PetroCaribe movement is gaining momentum every day, and there are so many important people involved that this affair is starting to look a little like the famous “Consolidation” trial of a century ago, in which many people – state clerks, ministers, parliamentarians, high-ranking officials, and even foreign citizens – were swept up in a huge state scandal.

As with the PetroCaribe Accord, the “Consolidation Trial’ took place after the country had taken a series of loans to “consolidate” or “stabilize” the Haitian economy. The loans were borrowed abroad but also from the Bank of the Republic of Haiti, headed at the time by French nationals. In fact, even though the bank was named as if it belonged to the Republic of Haiti, it was actually a private bank. So many loans had been taken out by different Haitian administrations that the debts were strangling the country.

But on Dec. 21, 1897, the government of Tiresias Simon Sam managed to settle this debt with his foreign creditors. But during the period of the economy’s consolidation, that is the period during which the government tried to free Haiti’s economy from foreign banks’ controlling grip by repaying the debt, some ministers and high officials made money off the deal, in other words, they enriched themselves on the back of the State through acts of corruption and embezzlement.

the Nord Alexis government ordered the arrest of all those who participated in this massive Treasury-depleting corruption scheme.

Taking advantage of debt financing, these high dignitaries filled their pockets by issuing fake treasury bills and other falsified documents, just like what happened with the use of PetroCaribe funds.

But after the fall of President Tiresias Simon Sam, an old general named Pierre Nord Alexis, known as Uncle North (Tonton Nò), took power. Very quickly, this illiterate old man, who had surrounded himself with high-level cadres, realized that Haiti’s elite, supported by France and in complicity with a good part of the State’s civil servants, senators, foreign ministers and traders, had embezzled considerable sums in the framework of the debt consolidation. This was in 1902.

Immediately, the general ordered an inquiry into the riches, lifestyle, and dealings of the former regime’s high officials. This investigation was conducted under the expertise of Commissioner Thimoclès Lafontant, and it made astounding discoveries of irregularities of an incredibly organized gang. Today, we would call it a criminal conspiracy.

Thus, after the revelations of the Special Commission of Inquiry’s report, in June 1903 the Nord Alexis government ordered the arrest of all those who participated in this massive Treasury-depleting corruption scheme. This series of arrests was followed by an extraordinary trial that still marks Haitian judicial annals.

While the Haitian population supported until the end the government’s actions during this trial known as the “Consolidation Trial,” also until the end the French government, in the name of protecting its nationals and those of Germany, tried to prevent the fraudsters from paying for their misdeeds.

The French and the Germans sent their warships to the waters off of Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves in an effort to intimidate Haiti during this historic trial. They tried everything to overthrow President Nord Alexis who, at the same time, celebrated with great pomp the centennial of Haiti’s independence on Jan. 1, 1904 at the Centennial Palace in Gonaïves.

The French and the Germans sent their warships to the waters off of Port-au-Prince and Gonaïves in an effort to intimidate Haiti during this historic trial.

Thus, against such opposition, the old general held firm and those whom the population called the “Consolidars” were tried and convicted between 1903 and 1904 on various charges. On Dec. 25, 1904, Christmas Day, the sentences of those convicted were handed down, including for several French nationals, among them the Director of the National Bank of Haiti, the French citizen Joseph de Myre-Mory, not to mention other bank managers (all foreign nationals, mostly French and German). Among the Haitians convicted were three of Haiti’s future heads of state. Their names were Cincinnatus Leconte, Tancrédus Auguste, and Vilbrun Guillaume-Sam.

This trial, which lasted more than a year (March 1903 – December 1904), is still considered today by historians as the largest and most famous trial that Haiti has known.

In spite of this very popular trial, President Nord Alexis was attacked and vilified by the opposition and Haitian elites, of course with France’s support, and they finally overthrew him on Dec. 2, 1908.

The “Consolidation Trial,” however, was not the only major trial against corruption and embezzlement of public funds in Haiti. Under Jean-Claude Duvalier’s dictatorship in 1975 there was another well-known trial. This so-called “Stamp Trial” was more like intellectual entertainment for law students and the curious rather than a real trial against traffickers and fraudsters.

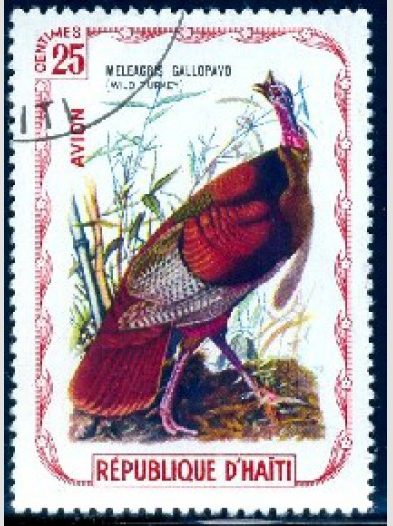

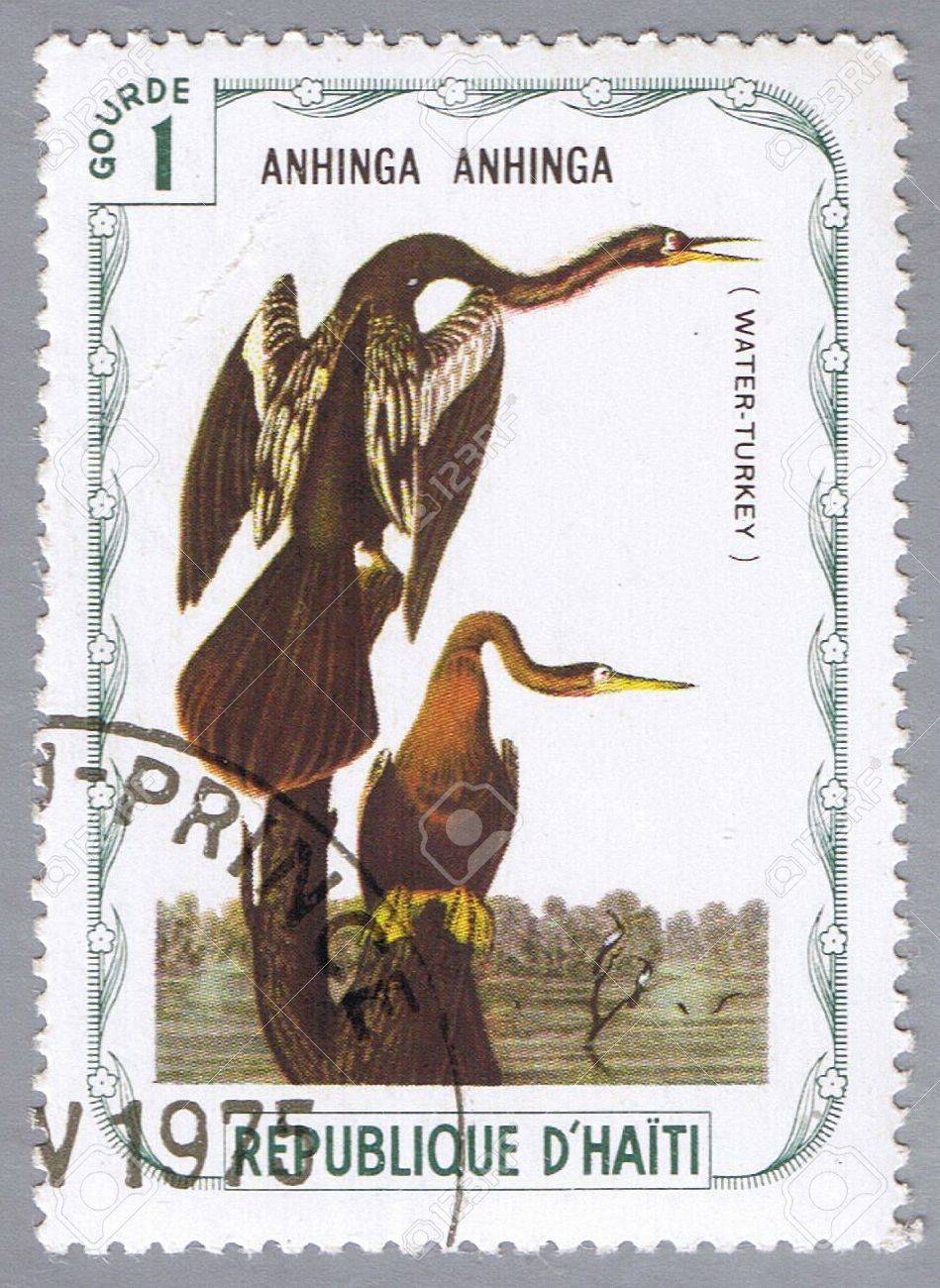

It all began with the publication of a book which paid tribute to the celebrated American painter and naturalist, John James Audubon. His famous book named “The Birds of America” was first published between 1827 and 1838.

Haiti also wanted to pay a tribute to this scholar of the American continent, who was born in Les Cayes in 1785. The government decided to print postage stamps drawn from the illustrations of Audubon’s famous work. The Haitian postal service had ordered stamps ranging from 5 centimes [in 1975, one U.S. cent] to 5 gourdes [in 1975, one U.S. dollar]. Because at that time the post office worked just as in any country, Jean-Claude Duvalier, who had succeeded his father François in 1971, also wanted to make his mark.

But as soon as Haitian authorities began printing these postage stamps, a pack of Duvalierist regime big shots, anxious to make a quick buck, set up a parallel trade in postage stamps to the detriment of the Haitian postal service. Except that, very quickly, their game was discovered. Thus, the Haitian Postal Administration had to withdraw stamps in circulation, and the Haitian government set in motion its police and justice system to identify the fraudsters. Very quickly, the culprits were identified by the regime’s secret police, immediately arrested, and imprisoned.

Among the most famous defendants, besides the Leroy family (Frantz, Marlène, Guy and Jean-Robert), we find Dr. Serge Fourcand, Pierre-Richard and Eugène Maximilian, Fritz Denis, René Exumé, and André Dérose Junior. All were accused of fraud and forgery. This trial attracted many people to the Port-au-Prince courthouse from Aug. 26 to Sep. 10, 1975, and it surprised the public, which was not used to this kind of public trial, especially since some big names of Duvalierism were accused.

For almost three weeks, the great tenors of the Port-au-Prince Bar and from across Haiti took to the podium to defend their clients or as representatives of the prosecution. Of the 10 defendants, one of whom was absent, three were acquitted and the others sentenced to between two and 15 years in prison. In reality, since they were all sons of the regime, some never set foot in a prison, and the others were quickly released. In fact, it was a trial purely for form. Some said it was a way for the regime to scare opponents of all kinds, but it had no intention of punishing its supporters.

Just as after the “Consolidation Trial,” some of those convicted in the “Stamp Trial” later returned to their places at the top in the Duvalierist hierarchy. These two trials did not come from the demands of the people or the opposition to the regimes in place. These were actions, certainly commendable, taken on the initiative of those in power. The people were not really involved in these lawsuits. So the culprits, whether they were the “Consolidars” in 1904 or the Stamp fraudsters in 1975, all had the opportunity to return to public life, either to be elected President of the Republic in the early 20th century or to reclaim their posts or functions under a different regime after their trial.

In the case of a PetroCaribe trial, things will necessarily be different. This trial, which is being forced by the demands and pressure of the opposition, socio-political actors, and the general public, will mark the end of the political and professional career of all those who will most certainly be condemned for corruption, embezzlement, fraud, forgery, etc.

This is why the PetroCaribe trial will be like a huge house-cleaning, and it will certainly affect Haitian society as a whole. The ramifications of this trial will be much more powerful than those of the “Consolidation,” and those convicted will undoubtedly be considered pariahs by the Haitian masses. It will be the first year of the new Republic.

Translated from the French original by Kim Ives.