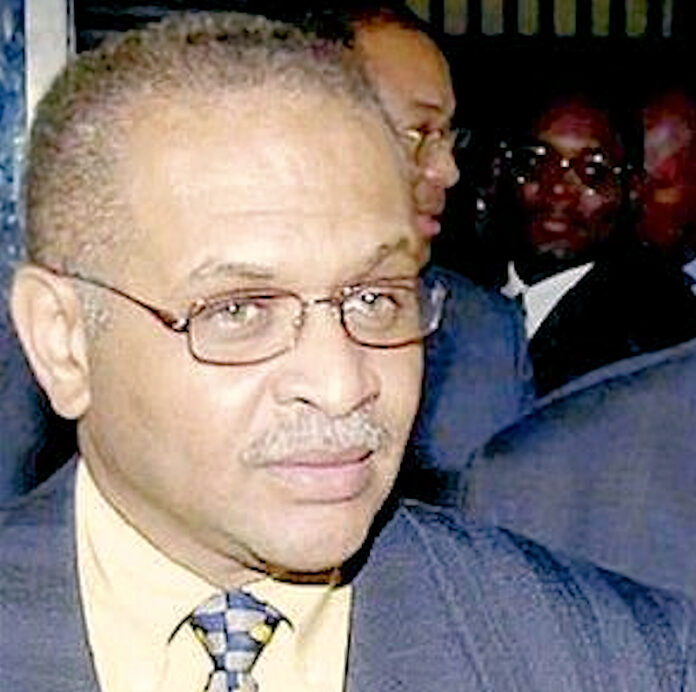

At 10 p.m. on Tuesday night, the Haitian Senate voted not to ratify former de facto Justice Minister Bernard Honorat Gousse to be President Michel Martelly’s Prime Minister.

The vote came after hours of rancorous, sometime chaotic, debate, and two brief closed sessions requested by Senators Youri Latortue and André Riché, both Gousse/Martelly supporters.

In June, Haitian deputies rejected Martelly’s first nominee, businessman Daniel-Gérard Rouzier, making this the new president’s second political defeat since he came to office on May 14.

This evening’s debate reached a stalemate around the “technical” stage of the Prime Minister’s review. A nine-member Senate commission submitted a report on whether Gousse was qualified to fill the post, according to six criteria from the Constitution’s Article 157. The commission reviewed whether Gousse was: Haitian-born, never having renounced his nationality; 30 years old or more; unconvicted of any crimes; an owner of property in Haiti and practicing a profession there; a resident of Haiti for the last five consecutive years; and “relieved of his responsibilities if he has been handling public funds,” as the Constitution stipulates.

the whole struggle was between those who wanted Gousse to have his moment in the spotlight and those who did not.

The commission determined that there was “controversy” around the final criteria. They found that it was not the Parliament but Prime Minister Gérard Latortue’s de facto government (installed after the 2004 coup against former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide) which “discharged” Gousse from his Justice Ministry in 2005, that is, which certified that he did not engage in corruption or other illegal activities. But as Senator Jean Baptiste Bien-Aimé, a commission member, argued in the session, “the executive branch cannot discharge someone from the executive branch.”

For that reason, the commission effectively kicked the final determination on Gousse’s eligibility back to the full 30-seat Senate for a general vote.

Senators allied to Martelly and Gousse insisted that the commission had to give a yes-or-no verdict on Gousse’s qualifications. Sen. Latortue, who was Gousse’s most vocal partisan during the debate, asked the report to be sent back to the commission.

Pro-Gousse senators also argued that former Prime Minister Jacques Edouard Alexis was ratified on the basis of an “executive discharge” in June 2006 under President René Préval. Some anti-Gousse senators said that ratification was unjustified; others argued that Alexis’ circumstances were different.

An absolute majority of 16 senators from Préval’s Unity party had formed a block vowing to vote down Gousse’s nomination. As Unity’s leader, former Senate president Joseph Lambert said, “the vote on Mr. Gousse must be and should be political.” He compared Gousse’s nomination to the hypothetical nomination of Roger Lafontant, a former Tonton Macoute chief and leader of a failed January 1991 coup. “A majority of senators would vote against that too, for political reasons,” he said.

Latortue and Riché were joined by Senators Anick Joseph, Steven Benoit, and Mélius Hyppolite, among others, in condemning the commission and the Group of 16 for introducing political considerations into the “technical” stage of the ratification process.

But Sen. Moise Jean-Charles took the podium to say that the hours of debate were nothing but “theater” because Gousse’s defeat was already guaranteed. Jean-Charles also asserted that Gousse had at one point even withdrawn his candidacy, knowing it was doomed. The charge prompted Latortue to call for the second closed-door session.

If Gousse had been cleared through the technical stage, he would have then had an opportunity to present to the Parliament and the nation his “general policy” declaration. That would have been followed by a debate and a vote, in which he would have also been rejected.

The pro-Gousse senators accused the Group of 16 of intransigence, illegal procedures, and holding Haiti hostage to their political agenda.

But the whole struggle this Tuesday was between those who wanted Gousse to have his moment in the spotlight and those who did not. The Group of 16 had written an open letter to President Martelly asking for him to withdraw the nomination, saying that Gousse was unacceptable for the “repression, arbitrary arrests and killings in the neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince” that were carried out under his auspices in 2004 and 2005. Some 4,000 people died from putsch-related violence during the 2004-2006 coup d’état, according to a study in the British medical journal The Lancet.

On the day of the debate, lawyer Mario Joseph of the Collective of Progressive Haitian Jurists (CJPH) wrote to the senators asking them “to reject Mr. Bernard Gousse as the Prime Minister-designate, to condemn the coup of Feb. 29, 2004, and to make him make amends for his involvement in the wrongs committed against the Haitian people during his time heading the Justice Ministry.”

The pro-Gousse senators accused the Group of 16 of intransigence, illegal procedures, and holding Haiti hostage to their political agenda. Lambert responded that it was Martelly who was being intransigent and illegal, because the Haitian Constitution instructs the President to select a Prime Minister nominee “in consultation” with the Presidents of both parliamentary houses. Martelly has unilaterally nominated both Rouzier and Gousse.

Rouzier was also rejected in the “technical” stage. The principal reason was because his Haitian passport had no U.S. visa markings in it, despite the fact that he owns a home in Florida, where his wife mostly lives, and frequently travels there. This led the deputies to suspect that he, as was rumored, may have obtained U.S. citizenship, thereby disqualifying him for the post.

The pro-Gousse/Martelly senators attempted to hobble the vote, neither voting for Gousse nor abstaining.

Toward the end, Sen. Hyppolite bitterly accused the Group of 16 of rushing to a vote before Gousse could present his general policy declaration, because “they don’t have the courage to defend their position before us, their fellow senators, or before the population.”

But Sen. Evalière Beauplan made several passionate interventions saying that the pro-Gousse faction was dragging the Senate through an unnecessary debate although it knew that he and his colleagues were “unshakable” in their resolve to vote Gousse down.

“I would vote against Gousse even if all the 29 other Senators voted for him,” Beauplan said, “because in 2004, he made me have to flee into exile.”