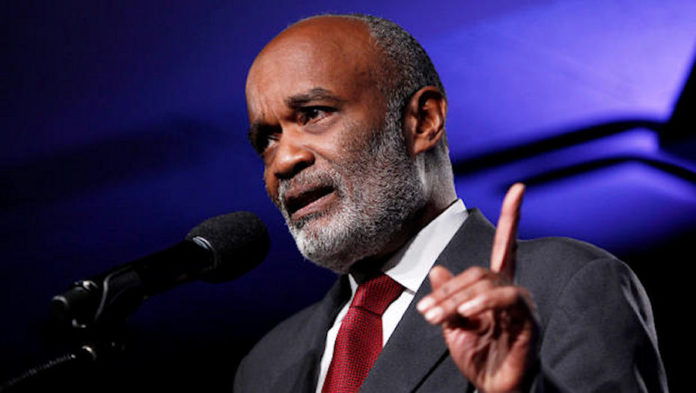

In 2009, former U.S. Ambassador to Haiti Janet Sanderson called him “Haiti’s indispensable man,” who was “capable of imposing his will on Haiti – if so inclined.” Another diplomat recently dubbed him one of Haiti’s “three kings,” along with former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide and the Duvalierists.

They were referring to former Haitian president René Préval, who died of an apparent heart attack on Mar. 3 in the capital’s mountain suburb of Laboule at the age of 74. Over the past 30 years, he had played one of the most important and contradictory roles of any politician in helping to briefly free Haiti from the political grips of Washington and the Duvalierists, nostalgic for the three decade (1957-1986) dictatorship of François and Jean-Claude Duvalier, only to lead the country back into their clutches by acquiescing to neo-liberal privatization campaigns, sovereignty-stripping international accords, minimum wage suppression, two foreign military occupations, and an “electoral coup d’état” a year after the 2010 earthquake.

Préval was laid-back and personable, but retiring. He shunned the trappings of power and trumpeting his accomplishments, unlike his successor Michel “Sweet Micky” Martelly, a ribald, flamboyant konpa music star. For example, Préval was so prone to informality that he scandalized some Haitians by wearing a white guayabera in the group photo at a hemispheric conference where all the other heads of state wore suits.

René Préval was born into a relatively well-to-do family in the northern Haitian town of Marmelade on Jan. 17, 1943. His father, an agronomist, served as President Paul Magloire’s Agriculture Minister in the 1950s but fled Haiti with his family in 1963. René was sent to study agronomy in Belgium and geothermal science in Italy. In 1970, he landed in New York, where he worked as a factory laborer, waiter, and messenger.

During his time abroad in the heady late 1960s and early 1970s, the young René had been politically radicalized by the progressive and anti-imperialist movements of the day. When he returned to Haiti in 1975, he gravitated towards anti-Duvalierist political circles in the elite.

After Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier’s fall on Feb. 7, 1986, Préval began to militate in the burgeoning popular movement that became known as the “Lavalas” or Flood, of which Father Aristide, a Salesian priest, was the emerging leader. He helped launch the Fred Coriolan Committee in 1986 and later Honor and Respect the Constitution, a human-rights and democracy advocacy organization which included other figures of the “enlightened bourgeoisie,” such as Antoine Izméry, Jean-Claude Roy, Patrick Élie, Charles Vorbe, and Father Antoine Adrien.

Haiti’s enlightened bourgeoisie was essentially an embryonic national bourgeoisie, as distinguished from the traditional comprador (import-export) bourgeoisie, which had always been economically and politically subservient to the U.S.. Préval and his friends, many of them the college-educated, radicalized children of the comprador and big-landowning grandon class, had an anti-imperialist dream of breaking Haiti’s neo-colonial chains to establish her “second independence,” as Aristide called it in his inaugural address.

This nationalist agenda merging with the broader democratic popular uprising against Duvalierist repression and corruption created the national democratic political revolution that culminated in Aristide’s victory in the Dec. 16, 1990 presidential election.

René Préval, along with Antoine Izméry, played a pivotal role in convincing the fiery Aristide, then hero of Haiti’s rural and urban masses, to become the candidate of the National Front for Change and Democracy (FNCD). The former priest had opposed participating in the 1990 elections, over which the Haitian army was effectively presiding (behind titular president Ertha Trouillot) and in which Washington-backed neoliberal candidate Marc Bazin had a $36 million war chest. Izméry put up about $500,000 for the campaign of Aristide, who won 67% of the vote. It was the first rout of U.S. election engineering in Latin America.

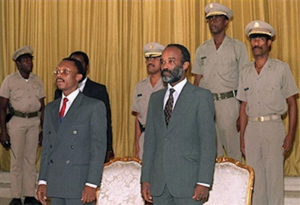

Following his victory, Aristide appointed Préval as his Prime Minister, pursuing policies of taxing the rich, fighting privatization, and uplifting the masses with health, literacy, and employment programs. But about eight months after Aristide’s Feb. 7, 1991 inauguration, the traditional bourgeoisie and grandon allied to overthrow and exile him on Sep. 30, 1991. After passing through the French and Mexican embassies, Préval eventually joined Aristide in Washington, DC, where a government in exile worked to undo the bloody coup d’état.

“You might be returned to power,” then U.S. Ambassador Alvin “Bourik Chàje” Adams told Aristide during one set of negotiations. “But your Prime Minister [Préval] – he’s definitely not coming back.”

Indeed, Aristide was forced to sacrifice Préval for other prime ministers – Robert Malval and Smarck Michel – more to Washington’s liking, but during those tumultuous, breathless eight months in 1991, the small-statured Préval had been engraved in the Haitian popular imagination as Aristide’s “twin.”

This association took on particular importance after Aristide’s Oct. 15, 1994 return to Haiti (on the shoulders of 23,000 U.S. troops), when a movement emerged calling for him to recoup the three years he had spent in exile.

“The clock stopped on Sep. 30, 1991,” declared Jesse Jackson at a January 1994 conference in Miami, FL, one of many to pressure for Aristide’s reinstatement. “President Aristide should serve out as president all the time he spends in exile.”

But Washington did not agree and began to pressure the people around Aristide, particularly those in the proto-party known then as the Lavalas Political Organization (OPL), which was headed by enlightened bourgeoisie representatives like Gérard Pierre-Charles and Father Antoine Adrien. Aristide began dragging his feet on carrying out Washington’s neoliberal dictates which were part of the deal for his return, most importantly privatizing Haiti’s state enterprises. As tensions between Aristide and Washington grew, OPL leaders began to parrot the U.S. mantra that privatizations were in Haiti’s interest, as well as new elections in 1995.

But popular calls for Aristide to recoup his lost three years grew, and, in response, the OPL found the perfect candidate to sell their U.S.-backed election: Aristide’s “twin,” René Préval.

Aristide was enraged that the OPL and Préval had abandoned him and pointedly refused to endorse Préval as a candidate until the day before his Dec. 17, 1995 election, when it was clear that Washington’s agenda could not be stopped.

As Russian revolutionary leader Vladimir Lenin warned over a century ago, “the bourgeoisie betrays its own self” and its own revolution. Similarly, during his first term as president (1996-2001), the once staunchly anti-imperialist René Préval capitulated to Washington’s demands to privatize state enterprises like the flour mill, cement factory, and telephone company, and signed an infamous international accord which gave Washington the authority to unilaterally enter Haitian territorial airspace and waters.

Nonetheless, Préval became increasingly at odds with his OPL sponsors, whose legislators blocked and hobbled his government until the Parliament expired in 1999. Meanwhile, as the OPL changed its name from Lavalas Political Organization to the Struggling People’s Organization, Aristide launched his own party in November 1996: the Lavalas Family (FL).

During his first term, Préval tried to institute an agrarian reform, but it was partial and short-lived. He also foiled a coup attempt by a group of police chiefs led by former soldier Guy Philippe, who would flee to the neighboring Dominican Republic where he set up an anti-Aristide paramilitary force.

By they end of his first term, Préval had strained relations with Washington, which was peeved that Aristide’s FL was returning to power via parliamentary and presidential elections in May and November 2000. On Feb. 7, 2001, Préval successfully passed the presidential sash to a re-elected Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the first such peaceful transfer of power in modern Haitian history.

Newly elected U.S. president George W. Bush’s administration wasted no time in launching an economic, political, diplomatic, and military destabilization campaign against Aristide’s second government, which was overthrown on Feb. 29, 2004. Aristide was exiled, at U.S. insistence, to Africa, out of the Western Hemisphere.

The de facto regime of U.S. puppet Prime Minister Gérard Latortue ruled for two years, holding elections on Feb. 7, 2006, in which Préval was reelected on the assumption that he would bring Aristide home. But Préval did not bring Aristide back and instead began to woo FL leaders to his own parties and platforms, primarily Lespwa (Hope) and Inite (Unity).

As a result, the FL split into two main factions, and Préval’s electoral council disqualified both from the 2010 elections, a move which even Washington and its allies saw as politically heavy-handed (although they continued to support the elections).

As was revealed by Haïti Liberté through cables it received from Wikileaks, then U.S. Ambassador Kenneth Merten worried that FL’s exclusion would make the party look “like a martyr and Haitians will believe (correctly) that Préval is manipulating the election.”

Despite Washington’s opposition, Préval established in 2007 a PetroCaribe deal with Venezuela, which provides Haiti with close to 20,000 barrels of oil monthly, built three power stations, and renovated the Cap Haïtien airport.

In his second inaugural address, Préval pleaded with the United Nations Mission to Stabilize Haiti (MINUSTAH) to “turn its tanks into bulldozers.” The appeal fell on deaf ears, and the foreign military force, deployed in June 2004, still occupies Haiti today. (Préval had also taken power under a UN military occupation in 1996.) The MINUSTAH imported cholera into Haiti in October 2010, sparking an epidemic which has killed some 100,000 and sickened over one million. The slow response of Préval’s health officials contributed to the disease’s rapid spread.

Préval was a fierce opponent of corruption and drug-trafficking, often complaining to U.S. officials that they were not doing enough to help him stamp out both. Nonetheless, he tolerated some clearly compromised officials in his own party, like Sen. Joseph Lambert.

Although not a charismatic public speaker like Aristide, Préval had a sardonic wit which either delighted or outraged people. For example, in 2006, peasants complained to him about the difficulties they faced. “We have to swim to get out,” Préval responded, which many interpreted as a way of saying it was every rat for itself. In 2008, when protesters announced a demonstration against food shortages and government austerity, Préval told them to “stop by the Palace and pick me up” to join them.

In his second term, Préval’s first prime minister, Jacques Edouard Alexis, was unseated in April 2008 by food riots and political intrigues. His second PM, Michèle Pierre-Louis, had been his business partner in a Port-au-Prince bakery in the 1980s. She resigned in November 2009 after being “increasingly frustrated and sidelined by President Préval,” according to a secret cable of former U.S. Ambassador Janet Sanderson, primarily when, with Washington’s encouragement, he overrode Parliament to keep Haiti’s minimum wage at $3 a day instead of $5. His third PM, Jean-Max Bellerive, was an admirer and protégé of Marc Bazin, the former World Bank economist who had briefly acted as de facto Prime Minister during the first coup against Aristide.

The country suffered four severe storms in one month in 2008, but the worst catastrophe on Préval’s watch was a massive earthquake that leveled the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area on Jan. 12, 2010. Due to a lucky schedule change, Préval narrowly escaped death. The tragedy became the defining event of the second Préval presidency.

“After I spent the night evaluating the destruction, I realized that I needed to go and organize the relief,” Préval told the Miami Herald after touring the devastated city on the back of a motorcycle. “Seeing people is not helping people.”

Washington unilaterally deployed 22,000 troops and took over the airport and relief efforts, sidelining Préval, who became increasingly resentful. At one public ceremony, Préval stood up and walked out of the room when UN Special Envoy and Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC) co-chair Bill Clinton took the microphone to speak.

In the first round of the Nov. 28, 2010 presidential election, Jude Célestin, the candidate of Préval’s party, came in second, according to the Haitian electoral council. But U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and the Organization of American States (OAS) intervened to tell Préval to put the neo-Duvalierist Martelly, who had placed a close third, in the run-off instead of Célestin. Préval again, as was his wont, complied. “It was an electoral coup d’état,” said Brazilian professor Ricardo Seitenfus, who was then the OAS Special Representative to Haiti.

During the electoral stand-off, the U.S. and UN even contemplated putting Préval on a plane and removing him from power. Seitenfus and Bellerive foiled the plan.

Despite not standing up to or at least denouncing U.S. bullying in both his presidencies, Préval did a great deal to strengthen relations and cooperation with Cuba (with which Aristide reestablished formal diplomatic ties as his last act in 1996) and Venezuela, to Washington’s dismay. Préval enthusiastically received then President Hugo Chavez in Haiti in March 2007, a visit which Sanderson complained was “giving Chavez a platform to spout anti-American slogans.”

Although he attempted to build mass organizations like Charles Suffrard’s KOZEPEP and parties like Espwa and Inite to offer an alternative to the FL, they never attracted as deep or widespread adherence and dedication. He surrounded himself with friends from the enlightened bourgeoisie like Pierre Denizé (chief of police), Alix “Boulon” Filsaimé (deputy), and Robert “Bob” Manuel (security secretary of state), who moved rightward politically from his anti-Duvalierist years and carried out brutal political repression against Haitian popular organizations during Préval’s second term. Manuel was also an unsuccessful prime minister nominee in 2008.

But perhaps Préval’s closest friend and éminence grise was celebrated radio journalist Jean Dominique, an enlightened bourgeoisie ideologue, who was gunned down in the courtyard of his radio station Radio Haiti-Inter on Apr. 3, 2000. Apparently, Préval had plans to tap Dominique to challenge Aristide as a presidential candidate in the November 2000 election. Préval wept profusely at Dominique’s funeral at the Sylvio Cator stadium. Until today, Jean Dominique’s murder has never been solved.

Préval is survived by three sisters, including Marie-Claude Préval Calvin, who, as a close political adviser, was almost killed in a 1999 assassination attempt, and Raymonde Préval Bélot, who has worked in Haiti’s diplomatic service and was the partner of Préval’s close friend Patrick Elie, who died in February 2016. Préval is also survived by two daughters, two sons, two grandchildren, and his widow, Elizabeth Délatour Préval.

He will receive a state funeral beginning on Fri., Mar. 10, 2017 at the Museum of the Haitian National Pantheon (MUPANAH) in Haiti’s Champ de Mars central square.

Today, the neo-Duvalierists, whom Préval and Aristide sought to uproot in their 1990-91 political revolution, have won Haiti’s presidency and parliament through anemic elections. This happened due to the discouragement, disillusionment, and demobilization of the Haitian masses as a result, in large part, of the compromises, sell-outs, and conniving of Préval and his coterie over the years. Despite his clearly sincere desire to build “national production,” as he discussed on the morning of his death with Deputy Jerry Tardieu, the once enlightened bourgeois leader, René Préval, who admired revolutionaries Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez, not only fell far short of achieving the democratic nationalist dream of his youth. He, perhaps unwittingly, helped bring about the exact opposite: the delivery of Haiti into the hands of Washington and the neo-Duvalierists.