She was the granddaughter of a British knight, who headed the largest trans-Atlantic passenger ship line, and the daughter of an early Time magazine managing editor.

Despite this lineage, which gave her an upbringing of wealth and privilege, Jill Stuart Martin devoted most of her life to working for the liberation of humanity’s exploited and oppressed, particularly the people of Haiti.

She died peacefully in the Bronx on Apr. 22 at the age of 83.

Living in Brooklyn’s “Little Haiti” for the later half of her life, she was well-known and beloved by residents and shopkeepers of the working-class neighborhoods along Flatbush Avenue, where she could often be seen driving minivans or station-wagons filled with the weekly newspaper Haïti Progrès. She worked there for almost three decades after its 1983 founding.

Jill loved people, and people loved Jill, who spent hours learning about their problems and trying to help whomever however she could. She was truly fascinated to learn peoples’ life-stories and seemed to know every bit of gossip in a two-mile radius around the Haïti Progrès office.

Having raised many children, she was the consummate mother, preparing food for and cleaning up after the constant stream of journalists, activists, and visitors which streamed through the office during the heady days of the Duvalier dictatorship’s fall to Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s rise and the subsequent coups d’état.

Reared in the Long Island Gold Coast towns of Locust Valley and Oyster Bay, she went to an elite girls’ boarding school in Maryland before attending Wellesley College in Boston. But she cut her college education short after two years to marry a graduating Yale student, Kenneth Appleton Ives, Jr.. The couple produced five sons in the space of six years, eventually settling in 1960 in Westchester County’s Bedford, NY.

There, Jill Martin Ives at first led the life of a typical suburban upper middle-class homemaker, driving her kids to school and church, attending PTA meetings, volunteering at the local hospital, and organizing Mt. Kisco Boys Club benefits.

But since she was a young girl, Jill had an innate class consciousness. She was embarrassed to arrive at grade-school in a chauffeur-driven limousine during the depths of the Great Depression and was drawn into friendships with the servants who ran the mansions where she grew up.

In Bedford, she began to help working-class youths from poor neighborhoods and broken homes, inviting them to live in the guestrooms of her young family’s home. As those young people multiplied and brought the drama of their own turbulent lives (crashed cars, violent confrontations, visits from the Sheriff, etc.) into her household , Jill’s marriage began to fray.

“You’re just fixing flat tires on a road covered with tacks,” a Haitian engineer working on an interstate highway being built near her home told her. “The problem is systemic. You will never be able to save all the lives of capitalism’s victims.”

That was when Jill’s life began to take a revolutionary turn. The Haitian was Ben Dupuy, a communist leader in the movement to overthrow dictator François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. Within a few years, she had left her marriage and Bedford to set up a sort of commune with Dupuy in Dutchess County’s Hopewell Junction, NY in 1970. Jill brought her five sons and Dupuy one of his sons and two daughters. Joining them all were a changing cast of Haitian revolutionaries and young American activists who would set up literature tables at nearby SUNY New Paltz or travel to anti-Vietnam-war demonstrations in Poughkeepsie or New York City. Although there was a focus on the Haitian struggle, the collective also became part of the Liberation Support Movement (LSM), which supported African liberation struggles. Political education meetings and debates would rage late into the night, sometimes for days on end, and housework was divided into brigades for shopping, cooking, and clean-up.

Jill would commute down the Taconic Parkway to New York to host a radio program about Haiti on Pacifica Radio’s 99.5 WBAI-FM and a similar television program produced at Downtown Community Television (DCTV) with Jon Alpert and Keiko Tsuno. She also became close friends with legendary folk singer Pete Seeger and his wife Toshi, who lived in the nearby town of Beacon.

Over the next 15 years, the collective household of revolutionaries and solidarity activists moved to different houses in Rockland County’s Valley Cottage and Spring Valley, NY. During that time, Jill and Ben formed the Friends of Haiti, which worked to raise consciousness and support among college students, church groups, and progressive organizations. It published an English newsletter, Haiti Report, and helped produce books and pamphlets for the Haitian Liberation Movement (MHL).

Increasingly, Ben and Jill traveled abroad to Europe, where other revolutionaries were being recruited, and to countries like Algeria and Cuba, which supported anti-imperialist struggles.

In 1983, Dupuy and his comrades founded in Brooklyn the weekly newspaper Haïti Progrès, with the slogan “le journal qui offre une alternative” (the paper which offers an alternative) to the other main Haitian weekly, Haïti Observateur, which was anti-Duvalierist but not anti-imperialist.

The progressive newspaper grew quickly in the revolutionary ferment that reigned during the Duvalier dictatorship’s final years. In addition to maintaining the office, Jill also helped organize Haïti Progrès’ growing library and collection of newspaper clippings and photographs. One could often find her sitting with a tea late at night clipping, pasting, and marking newspaper articles on white sheets of paper and then filing them in manila folders, which found their way into giant filing cabinets she organized with color-coded tabs.

For years, she was also the main person who drove in the morning’s wee hours on Wednesday to the Long Island City printing plant to load thousands of papers into boxes and then drive them to the airports, where they were sent on flights to Haiti, Florida, Canada, and France. The sight of this small, thin woman loading dozens of 50 lb. boxes into a van during a frigid winter night astonished more than one helper.

Jill Ives committed what Guinea Bissau’s revolutionary leader Amilcar Cabral called “class suicide.”

But Jill’s principal contribution to the Haitian struggle was “outreach.” Her official responsibility was to raise financial support for the political work, which she adroitly did. However, in the course of that work, she recruited many people who had nothing to give but their labor.

She was truly interested in and moved by the struggles that people faced in their lives. Just as she had done in Bedford, she would go out of her way to find housing for a young single mother or a doctor for a someone with a serious illness. At the same time, she tried to engage them in the struggle.

Through all these years, remarkably, she only traveled to Haiti once, for Aristide’s February 1991 presidential inauguration. She was the epitome of self-sacrifice, always ready to support others while she herself “held the fort” in Brooklyn.

Around 2010, this woman whose life revolved around talking to people began to experience difficulty speaking. She attributed the problem to mold which had plagued a basement apartment where she briefly lived. Distrustful of Western pharmaceutical medicine, she tried herbal and alternative remedies, but to no avail.

Soon, she was unable to continue working, becoming disoriented and a danger to herself and others. Her sons found Kittay House, a senior community in the Bronx, where she spent her final years as her condition worsened. Over the last five years, she completely lost the ability to talk or walk. But her expressive blue-eyes would laugh, narrow, widen, and sometimes weep when listening to the stories of many extended family members who dropped in to see her. Those looks, and the squeezes of her hand, became the last means of communication for a woman whose life was fueled by conversation.

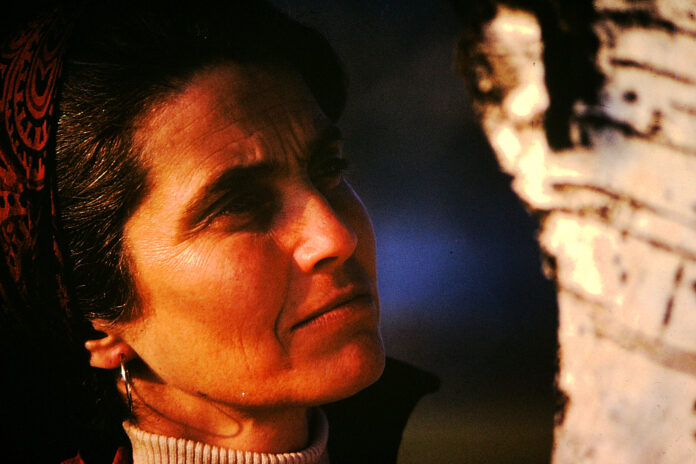

Jill Ives committed what Guinea Bissau’s revolutionary leader Amilcar Cabral called “class suicide.” She traded in a life of leisure and comfort for the rigors and deprivations of the trenches of Haiti’s democratic struggle. In the course of it, she inspired many and touched the lives of countless people who will remember her great beauty, selfless spirit, and boundless love for humanity.

A tribute to Jill Ives’ life and memory will be held at Guarino Funeral Home, 9222 Flatlands Ave. in Brooklyn, NY on Sat., May 4 from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m.. A reception will then be held at Haïti Liberté newspaper, 1583 Albany Ave. in Brooklyn from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m.. All who knew and loved Jill are welcome to attend.

[…] sur la construction de la route 684 à travers le comté de Westchester, NY, où il a rencontré Jill Ives, qui est devenue sa partenaire de longue date. Après des divorces, les deux ont fusionné leurs […]