Maria Batlle is a prominent Dominican artist, who established a foundation to explore educational and empowerment strategies for deaf children. This is the second in a series of articles she is writing for Haïti Liberté. She will examine themes relevant to both the Dominican and Haitian people, towards the goal of fostering greater understanding, solidarity, and progress. Contributing to this week’s article was writer Stephen Levien, who spends most of his time in the Dominican Republic and Haiti. – Kim Ives

The history of Haiti is inextricably linked with its music. New musical forms, styles, textures and energies have invariably coalesced with the social and cultural evolution of the Haitian people. It would be impossible to overestimate the importance of music in this regard, or for Haitian history to be understood in any other way. For example, any movie that attempted to capture the revolutionary spirit that led to the 18th century overthrow of French oppression would have as its initial and most daunting task to recreate the music that accompanied and embodied that effort.

Later chapters of Haitian history provide more accessible examples, such as the Haitian singer, writer, and human rights activist Martha Jean-Claude, whose plays and songs have been described as among the most precious jewels of Haitian history. Fearless and unintimidated, her artistic pursuits ultimately led to her arrest in 1952 while pregnant, and she gave birth two days after getting out of prison. Known as the daughter of two islands, she moved to Cuba, where she continued to speak out against Haitian government oppression of the Haitian people and, later, in defense of the Cuban revolution, all while promoting Haitian art forms.

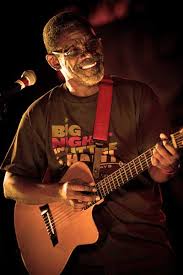

Haitians – particularly those living in South Florida – may well have experienced the Haitian activist musical tradition through the late Manno Charlemagne, an anti-Duvalierist protest singer and former mayor of Port au Prince, who became a fixture at Miami Beach’s Tap Tap Restaurant for many years and remained a galvanizing force until the end.

Of course, the linkage between music and activism is not an exclusively Haitian phenomenon, and it is not only Haitian artists who find themselves in a diaspora.

“I think the challenge is keeping your roots alive,” says Galician Bag Piper Cristina Pato. “Since I left Syria, I find myself experiencing emotions far more complex, like can a piece of music stop a bullet?” notes clarinetist Kinan Azmeh. “The revolution, chaos, I had to leave” says Kamancheh player Kayhan Kalhor from Iran. “In 1966, during the cultural revolution, my father asked me to learn music to escape,” says Wu Man from China. These artists, just like the “Daughter of Two Islands” Martha Jean-Claude, left their motherland to keep their roots, and their voices, alive.

Ultimately, many found a musical home in the United States. In 1998, a group of musicians joined famed cellist Yo-Yo Ma to develop a culture of collaboration and “passionate learning.” They called their ever evolving musical and education project “The Silk Road Ensemble.”

“They are living representations of the impossible possible,” says Steve Seidel, the director of the Arts in Education Program at Harvard University, where their project is based.

Faced with the existential challenges that these times of globalization and dehumanizing technologies present, Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble reminds the world of the timeless value of building community through collaboration: the opportunity for artistic enterprises to coalesce gradually over time, and, through a multitude of techniques of sound and music, the transformation of curiosity and imagination into art. The simple miracle they represent, the value of a group of people unified in mind and spirit, is still the most important.

The collective is made up not only of musicians but of teachers, visual artists, and sundry producers, all defenders of the belief that music is a primary tool for change. The members of Silk Road see the challenges that different cultures could present or the supposed barriers of the different languages from a unique and open angle. They collaborate with experts and institutions that understand that the arts are a fundamental part of society and, therefore, a fundamental part of the education system.

Lori Taylor, an education specialist at Silk Road, shares that as soon as Yo-Yo Ma learned about the high percentage of students dropping out of high schools in Chicago, his response was: “How can we help?” She believes that having a constant commitment to the arts can be a powerful learning experience for students, as it connects them with their own traditions and with themselves. That is how Silk Road Connect was born, one of the many artistic program Silk Road has implemented with high schools.

At the most personal level, being with Silk Road is to remember the power of the arts to help us be, individually and collectively, the best version of ourselves.

“One feels an explosion of energy and beauty that happens thanks to his generosity, curiosity, humility and virtuosity.” Mr. Seidel describes his last 10 years working with Silk Road at Harvard as moments of seriousness, urgency, joy, and magic. “The constant state of the students wanting to learn from the members of Silk Road makes their learning visible, and that is an invitation to everyone to learn with them.” In six years, the Silk Road has received more than 500 educators from all over the world with their annual institute “Arts and Passionate Learning.” Each institute is a “pop-up” laboratory to study how the arts can help people learn and teach.

“I’m an educator, and I think that means I’m basically a person full of hope,” concludes Mr. Seidel. “At the most personal level, being with Silk Road is to remember the power of the arts to help us be, individually and collectively, the best version of ourselves.”

Those who admire Haitian culture and values will no doubt feel a note of kinship with him, Yo Yo Ma, and their entire coterie of inspired participants.

We might wonder if a piece of music can stop a bullet, yet one thing is certain: no bullet will stop artists and educators from trying.

“Tout kontinan kanpe pou l fè oun sel patri. Mwen gen fòs, mwen gen fòs, mwen gen fòs” Martha Jean-Claude

(Let the continent stand as a single nation! I am strong, I am strong, I am strong)

“Mwen gen fòs” Lyrics by Martha Jean-Claude, transcribed and translated from Kreyòl by Dady Chery