Holy Ghost (Spiritain) Father Jean-Yves Urfié died in the early morning hours of Feb. 10 in the Paris suburb of Chevilly Larue. The cause of death, according to his close friend Jean-Michel Gelmetti in an online tribute, was Covid-19. He passed away at the Holy Spirit Seminary, which was fitting given that he had faithfully served his Catholic Church order year in-year out since being ordained in 1963.

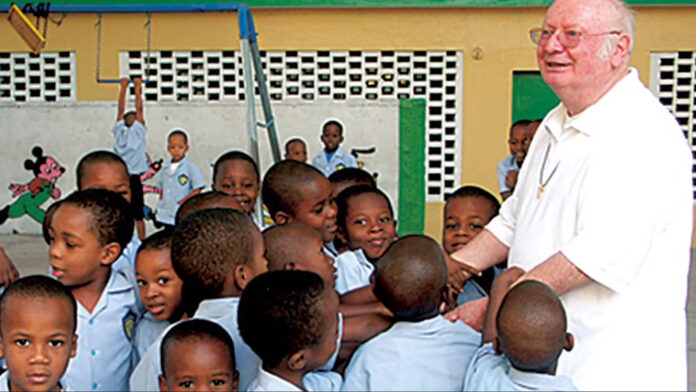

But the principal beneficiary of Urfié’s commitment, wisdom, humor, knowledge, and love was the Haitian people.

He spent over 30 years serving Haitians and their struggle for freedom from repression and exploitation either in Haiti or in exile, where he served Haitian migrants (in Brooklyn, NY, and in French Guyana). I was lucky enough to know and work with him during many of those years.

Father Urfié was born on Aug. 4, 1937 in Rennes, Brittany’s capital, and later educated in New York. In 1964, he began to teach chemistry, physics, and cinema at the Petit Séminaire Collège Saint-Martial, a Spiritain-run boys school in Haiti. Asked why he chose that country, he clarified: “I did not choose Haiti. I was sent to Haiti,” adding that he developed love for it because of “the courage of Haitian farmers and workers who fight for their survival, and the courage of a people who freed themselves from the dictatorships of the Duvaliers, Namphy, Cédras, etc.”

While at Saint-Martial, in addition to teaching, he and other Spiritain-teachers helped hide those threatened with death by François “Papa Doc” Duvalier’s regime. He was also involved with journalist Jean Dominique’s “Ciné-Club,” later banned by the dictatorship because of the consciousness-raising films it showed Haiti’s youth.

In 1969, Duvalier threw all the Spiritains out of Haiti. Urfié worked first in Gabon for two years and then served Haitian migrants in Brooklyn (1971-1985). During that time, he and the other priests founded “Sèl,” a journal originally in French and Kreyòl which they quickly switched to Kreyòl only, the language of all Haitians. Copies were smuggled into Haiti and avidly circulated.

Urfié and most of his Spiritain brethren returned to Haiti after Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier’s fall in 1986. Over five tumultuous neo-Duvalierist years from 1986 to 1990, they came to form what could be called a “religious kitchen cabinet” for the young liberation theology-influenced priest, soon-to-be-president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

“You can’t serve two gods at a time. You can’t serve God and money.”

“You have to be radical if you believe in the Gospel,” he explained to the New York Times in 1994. “If you have a cancer, you go to the roots to remove the cells. We have a cancer here called the macoutes.”

In 1991, the same year Aristide was elected in a landslide, Urfié and a team of journalists founded the country’s first and only Kreyòl language newspaper: Libète. That’s when I met him.

As editor of the then-clandestine biweekly newsletter Haiti Info, I would arrive after dark with the news and human rights violations reports we had received from our “grassroots stringers” – cassettes or scribbled notes from union members, peasant leaders, teachers – and I would trade information and sometimes photos with Urfié and his team. Even though we both spoke English, we never conversed in that language. It was always kreyòl – lang pèp la (the people’s language).

Libète articles covered politics, human rights, social movements, as well as health and agriculture. It also carried funny and sometimes biting political cartoons. But after 43 issues, on Sept. 30, 1991, it was brutally shut down, as were Kreyòl language, consciousness-raising radio stations, when the army, with the support of the U.S. government and local bourgeoisie, overthrew Aristide in a bloody coup.

A year later, however, Libète was back on the streets, printing a weekly run of 2,000 papers. It was distributed only in Port-au-Prince, since the countryside was too dangerous for newspaper-sellers. Even in the capital, hawkers were attacked by soldiers and paramilitary thugs. One was forced to eat an entire issue.

The paper ran out of funding in 1996, and Urfié returned to Saint-Martial to head the secondary school. He then served at the Vatican in Rome for four years.

Not surprisingly, Urfié returned to Haiti in 2004, this time to found a parish in Furcy and to work on various local social and agricultural programs, including youth-led reforestation. He left Haiti in 2008 but was back after the earthquake in 2010, of course, as were so many, determined to help with the post-earthquake disasters – political, economic, and environmental.

Urfié was among the first to denounce Monsanto’s distribution of hybrid and genetically modified seeds in Haiti, saying the country did not need them (it did not). He also pointed to Monsanto’s repeated violation of laws around the world and in the U.S. and was critical, too, of the foreign non-profits “that spend almost all their money on themselves – they are here to help themselves rather than the Haitians.”

That was in 2011 and the last time we met in person. After ripping into Monsanto, he told me that his faith is what has always kept him dedicated to fighting injustice, repression, and oppression.

“The capitalist system is morally against what God said. In it, profits are more important than people,” he said. “You can’t serve two gods at a time. You can’t serve God and money.”

Even into his eighties, Urfié never ceased to make videos, write articles, and even create and post on his own website, always with the idea of liberation and of progressive social change. One recent post on his site mocked Donald Trump: “The king is naked, but he doesn’t know it.”

Just a few months ago, he sent me an article for Golias Hebdo entitled “Haiti: Refusing to Submit.” In it, he warned then-President Jovenel Moïse: “Haitians will not accept one more year of oppression and crying inequalities.”

And only a few weeks back he asked me to help circulate his a new video – “Is Vodou Satan?” – a documentary he produced with the help of filmmaker Rachèle Magloire. He made it to denounce pastors who blamed the earthquake on “voodoo” and to normalize, demystify, and destigmatize peoples’ beliefs.

On his website, Urfié wrote about “complete liberation,” meaning physical, intellectual, and economic liberation, which includes justice and peace. “We also have to help open the eyes of others so that they can see the roots of their chains.”

Thank you, Jean-Yves, for helping to open the eyes of so many.