Last week’s installment examined charges that Senator Youri Latortue, whom the U.S. Embassy described in a secret cable as possibly “the most brazenly corrupt of leading Haitian politicians,” was involved in drug trafficking, kidnapping, and other illegal activities. We continue our portrait of this powerful politician through secret U.S. Embassy cables provided to Haïti Liberté by the media organization WikiLeaks.

Latortue vs. Alexis

One of Youri Latortue’s biggest political rivals was then Prime Minister Jacques Edouard Alexis, who also hails from Gonaïves. A colleague of Latortue described how “Senator Latortue paid protestors to demonstrate and cause disruption to the ceremonies” celebrating Gonaïves’ anniversary, which Alexis attended, wrote U.S. Ambassador Janet Sanderson in a Nov. 20, 2006 cable. “Senator Latortue often exploits local gangs for his own purposes in this way.”

Sanderson commented at the end of her cable that “Latortue’s activities are a cause for concern given his presidential ambitions for 2011. Prime Minister Alexis has gone as far as to ask for the USG [U.S. government] to ‘arrest him’, as has Préval’s advisor Bob Manuel.”

The political skirmishing between Alexis and Latortue continued throughout 2007, with the U.S. Embassy following it closely. The biggest row came after “Chief judge for the court of appeals, Hughes St. Pierre, died in Port-au-Prince on April 24 in a traffic accident,” Sanderson reported in a May 15, 2007 cable. The judge was presiding over the La Scierie trial, in which various Aristide government officials and policemen were accused of carrying out a “massacre” in St. Marc, a charge which has since been completely discredited. “St. Pierre, 75 years-old, was getting off a a ‘tap tap’ (a small truck converted for public transport) on the busy Delmas thoroughfare when another vehicle struck him. St. Pierre on April 13 had issued a ruling on a motion to dismiss the charges brought by several La Scierie defendants, declining to make a final decision and asking the examining magistrate in the case to re-examine several witnesses.” Two days after St. Pierre’s death, former Lavalas deputy Amanus Mayette was released by the replacement judge, which “unleashed a torrent of criticism and conspiracy theories from [Lavalas Family] FL opponents,” who argued that “the La Scierie defendants would go free and not reveal the involvement of President Préval and other officials in crimes committed under Aristide.”

Sanderson matter-of-factly commented at the end: “Apart from trying to link the judge’s death to a government conspiracy to absolve the La Scierie defendants, Youri Latortue and his allies in the Senate appear to be using this opportunity to derail justice reform legislation.”

When Alexis met with Sanderson later that May, he said that Latortue’s “parliamentary investigation into the death of [St. Pierre] and calls to remove the justice minister” were simply an “attack […] really directed against him, orchestrated by Youri Latortue,” the ambassador wrote in a May 25, 2007 cable. Alexis “claimed that Latortue had organized the demonstrators who had thrown rocks at him during his visit to Gonaïves… to attend St. Pierre‘s funeral.” Alexis said how even his “supporters among the Gonaïves elite” asked to meet him “outside of Gonaïves, because they did not feel safe holding the meeting in the city” because “the local police force was corrupt and controlled by Latortue.” Sanderson concluded, almost bemusedly, that even the powerful Prime Minister’s “supporters in his own home town were running somewhat scared.”

Five days later, Sanderson wrote Washington that “political observers believe that Senator Youri Latortue is either instigating or encouraging the disturbances” in the northwestern city because “ongoing violence in Gonaïves discredits both the government and MINUSTAH, raising Latortue’s profile as a powerful alternative to the current order.”

She continued: “While Youri Latortue may have become something of a combination boogeyman and pat answer for government officials seeking to explain their failure to improve conditions in Gonaïves, a broad spectrum of contacts with knowledge of the situation almost unanimously believe that Latortue orchestrates an anti-government/anti-MINUSTAH campaign and manipulates the local gangs to his own political ends. Specifically, they charge that Latortue encourages lawlessness in Gonaïves to discredit the government and to bolster his case for the re-establishment of Haiti‘s army, while strengthening his own power base in the region.”

Latortue’s Charm Offensive

The U.S. Embassy was starting to be alarmed at the trouble Latortue was creating – in a Jun. 20, 2007 cable, for example, Chargé d’Affaires Thomas Tighe remarked that Youri was “suspected of supporting, if not participating, in criminal activity.” But perhaps Latortue had some spies of his own in the Embassy who gave him a heads-up about Washington’s growing concern, because he requested a meeting with the Embassy and got it on Jun. 18, 2007.

In a Jun. 27 cable entitled “YOURI LATORTUE REACHES OUT,” Sanderson describes how the Senator “expressed his desire to have better relations with the embassy and expand the reach of his political party” and “explained that he supported forming an army.” She noted that “Latortue’s profile as a leading opponent of the government and future presidential candidate has risen sharply in recent months, even though informed Haitians widely assume that he was involved in drug trafficking and is still directly linked to criminal activity in his home base in the Artibonite.” Alas, she concluded, “Latortue’s influence makes it increasingly difficult for post [the Embassy] to shun him completely, but we will maintain our policy of keeping him at arms length.”

U.S. Ambassador Janet Sanderson flagged “Latortue’s blatant political ambition” and called him “the poster-boy for political corruption in Haiti.”

Latortue told the Embassy political officer with whom he met that “his goal was to transform his organization [LAAA] from a regional to a national party.”

“Latortue stated that the international community plays a big role in Haitian affairs and that he must reach out to it if he is to be a successful, national political leader,” Sanderson reported. “He claimed to have had good relations with the US Embassy in the past, but that the relationship soured beginning in 2004. Unprompted, Latortue acknowledged that some people believe he is a drug trafficker. He retorted that these were unsubstantiated claims by his and his ‘uncle’s’ political enemies.”

Latortue’s sucking up to the Embassy appeared to have been rather transparent. “He closed his remarks on his political ambitions by avowing that he has always been, and will continue to be, a friend of the United States” Sanderson wrote. “He said that he receives from Cuba and Venezuela offers to visit, but always declines because these countries ‘do not represent his way of thinking.’ He also claimed to have counseled other government officials and parliamentarians that accepting these offers would appear to be playing off the United States and Venezuela/Cuba against each other.”

Youri also said he favors “an obligatory one year service for 18-20 year olds” in a new Haitian “public security force” that “should number between 1,000-2,000.” (Haiti has tens of thousands of young men in that age group.)

Although Sanderson flagged “Latortue’s blatant political ambition,” she concluded “in Haiti’s see-no-evil -hear-no-evil political culture, many Haitians naturally assume that Latortue will play an increasingly important role in politics as he consolidates his power, and view him as a serious presidential contender, even as he becomes the poster-boy for political corruption in Haiti.”

The Embassy kept collecting many reports from many quarters about Youri’s devilry. For example, one “civil society representative” (whose name is removed for his safety) “believed that Gonaïves suffered from insecurity ‘that was a form of opposition to the GoH’ caused by politically ambitious persons, ‘some of whom should be behind bars, but are seeking office. You know who I am talking about.’” He said that “because of his long established ties with the gangs, Latortue is part of a strong minority able to disrupt events that support Prime Minister Alexis, as seen when demonstrators threw rocks at Alexis during Judge Hugues St. Pierre‘s funeral” and “claimed to know definitely that Latortue is stockpiling arms.”

Youri Wins… for Now

Latortue’s chance to bring down Alexis’ government came in early 2008, when protests and eventually food riots began to sweep Haiti over the high cost of living.

“Senator Youri Latortue immediately pronounced that the ‘government in power has failed,’ and that the people’s ‘patience has limits,’” wrote Sanderson in a Feb. 15, 2008 cable. In sharp contrast to his posture at the U.S. Embassy only eight months earlier, Latortue “accused the government of pursuing ‘neo-liberal’ policies responding to the demands of ‘international financial institutions’ rather than to the needs of the Haitian people.”

Sanderson concluded that “ten percent inflation and sixty percent joblessness have no short-term cures. The cost of living is an issue tailor-made for demagoguery and browbeating the government, which Senator Latortue is spearheading for now.”

On Apr. 12, 2008, the Haitian Senate ousted Alexis, and it was largely thanks to you-know-who. “Senator Youri Latortue,… who ultimately helped engineer the downfall of PM Alexis, accurately predicted to the Canadian Ambassador Alexis’ fall before it happened,” Sanderson wrote in her Apr. 24, 2008 cable. “It was Senator Latortue who called for the Senate to vote on Alexis’ fate in the April 12 Senate interpellation.”

Ironically, in meetings with the U.S. Embassy three months later, Latortue “put the blame for the April food riots on Fanmi Lavalas elements” saying that they were “organizing the violence.” Sanderson reports in a Jul. 17 cable. (Ironically, during the food riots, the Lavalas Family had a large rally in Cité Soleil seeking to calm the population.)

At that same meeting, Latortue outlined his security program as “1) expanding Haitian National Police (HNP) coverage of the country… 2) creating a coordinated national intelligence institution; and 3) establishing an army or a gendarmerie.”

Sanderson concluded with her usual shrug: “With a shady and possibly criminal past, Latortue is an unavoidable presence in the Senate… Embassy nevertheless remains conscious of Latortue’s shady past (which may well continue into the present) and of his possible drug associations. While Latortue is the most articulate and media-savvy of Senators, his messages to foreign diplomatic interlocutors are carefully tailored around his political agenda. Embassy will continue to maintain discreet, working level contact with Latortue in the interest of gathering information.”

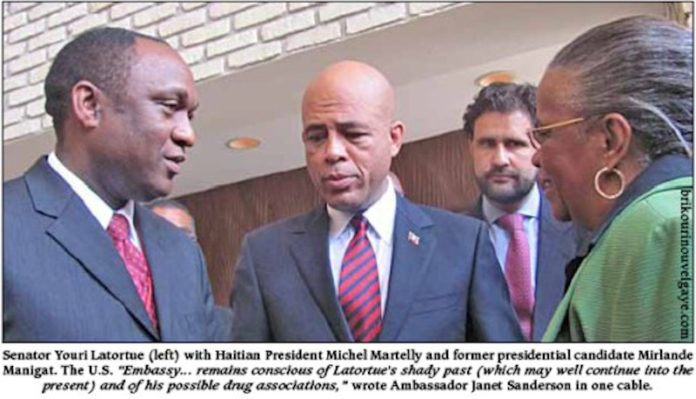

The New Latortue/Martelly Alliance

The Embassy cables in 2009 continue to track Latortue’s political challenge to the Préval camp but also international leeriness of him. For example, a Jan. 23, 2009 cable explains that Michaëlle Jean, then Canada’s Governor General, on a tour of Haiti “skipped the port city of Gonaïves to avoid having to meet Artibonite Senator Youri Latortue who is widely believed to be associated with drug trafficking and thus unable to get a Canadian visa.”

Also the Haitian President began to tell the Embassy that he was worried about Latortue’s rise, according to a May 12, 2009 cable. “These were Préval’s first remarks to the Embassy that he views Artibonite Senator Youri Latortue — whose Presidential ambitions are thinly veiled — as a political threat,” it reads.

Ironically, neo-Duvalierists like Youri Latortue and Michel Martelly, with backing from Washington, did end up knocking Préval’s candidate, Jude Célestin, out of the March 2011 Presidential run-off. They now are trying to ram through their pet project of restoring the Army, but as Rouzier’s rejection shows, Haiti, politically, is “tè glisse,” or slippery ground.

Meanwhile, Youri Latortue continues to carry on his business, secure with his parliamentary immunity and his “je sèch,” approach, Kreyòl for bald-face lying. For example on Jun. 14, 2011, he held a book signing for his new title “My Fight in the Parliament,” a self-serving account of his years as Senator. In it, he denounces the Aristide and Préval governments’ failure to carry out judicial reform, the very same reform he worked so hard to block as Chairman of the Senate’s Justice committee, the U.S. Embassy cables show.

In the new book, he also describes how he worked hard in the Parliament to “give the institution another image.”

Best of all, as he signed his new book, Youri Latortue was also signing one of his other titles: “The Problem of Drugs.”