Crowds cheered as local lawmakers on Aug. 18 unveiled a street sign showing that Rogers Avenue in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn would now be called Jean-Jacques Dessalines Boulevard, after a Haitian slave turned revolutionary general.

When Dessalines declared Haiti’s independence from France in 1804 after a 13-year slave uprising and civil war, he became the Americas’ first black head of state.

Supporting the French colonial perspective, leaders across the Americas and Europe immediately demonized Dessalines. Even in the United States, itself newly independent from Britain, newspapers recounted horrific stories of the final years of the Haitian Revolution, a war for independence that took the lives of some 50,000 French soldiers and over 100,000 black and mixed-race Haitians.

For more than two centuries, Dessalines was memorialized as a ruthless brute.

Now, say residents of Brooklyn’s “Little Haiti” – the blocks around Rogers Avenue, home to some 50,000 Haitian-Americans – it’s time to correct the record. They hope the newly renamed Dessalines Boulevard will burnish the reputation of this Haitian hero.

Opposition to Dessalines

Other New Yorkers aren’t so sure.

The New York City Council’s vetting committee labeled Dessalines a “possibly offensive historical figure,” tacitly referencing the massacre of French citizens that followed Haiti’s revolution.

Just after declaring independence, in early 1804, Dessalines discovered that local French colonists were plotting to overthrow his new government. He ordered all remaining French citizens in Haiti, except for a few French allies, to be killed.

My research indicates that between 1,000 and 2,000 white landowners and their families, merchants and poor French were executed, always in a very public fashion. Some estimates are as high as 5,000.

Dessalines, who protected all British, American and other non-French white people living in Haiti, justified the killings as a response to acts of war by France. Despite Haiti’s declared independence, French imperial forces continued to threaten invasion from their military outpost in Santo Domingo, modern-day Dominican Republic.

To his critics, however, Dessalines’ massacre amounted to “white genocide.”

The limits to Jefferson’s vision of equality

In researching Dessalines for the biography I am writing, I found that that he was in many ways cut from the same cloth as Thomas Jefferson, George Washington and other American revolutionaries.

Dessalines was an Enlightenment thinker who espoused life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. And he was willing to use strategic, bloody violence to free his people from colonial rule.

But in his commitment to black equality he was far more radical than America’s founding fathers, who freed the U.S. from England but let black Americans stay in chains for another nine decades.

In June 1803, when Dessalines began planning for independence, he wrote to President Thomas Jefferson.

Like Americans, he reported, Haitians were “tired of paying with our blood the price of our blind allegiance to a mother country that cuts her children’s throats,” he said. They would fight for their freedom.

Jefferson never responded.

In Dessalines’ philosophy, race was an ideological concept.

Dessalines’ vision of an autonomous black state – a nation founded by enslaved people who killed their colonial masters – alarmed the patrician Virginia plantation owner, Jefferson’s letters show. The U.S. was also being pressured by southern slave states and French and British diplomats to shun Haiti.

Rather than reckoning with the ills of racial oppression and colonialism, most prominent thinkers across the Americas and Europe interpreted Dessalines’ war as an example of African barbarity.

Haiti was run by a “hord of ferocious banditt” and led by “Barbarous Chieftains,” commented one British observer in 1804.

Pushing the Enlightenment further

This racist view of Dessalines persisted for two centuries. Today, modern scholarship is redeeming Haiti’s founding father.

Dessalines challenged the universalist rhetoric of the 1789 French Revolution, when idealists toppled their monarchy demanding “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité” – freedom, equality and fraternity.’

Dessalines’ revolutionary fervor earned him international diplomatic isolation.

Yet the French continued to use enslaved labor to produce sugar, coffee and other crops in the Caribbean. Dessalines said France had shrouded their colonies in a “veil of prejudice.” He insisted that true egalité required black liberty, too.

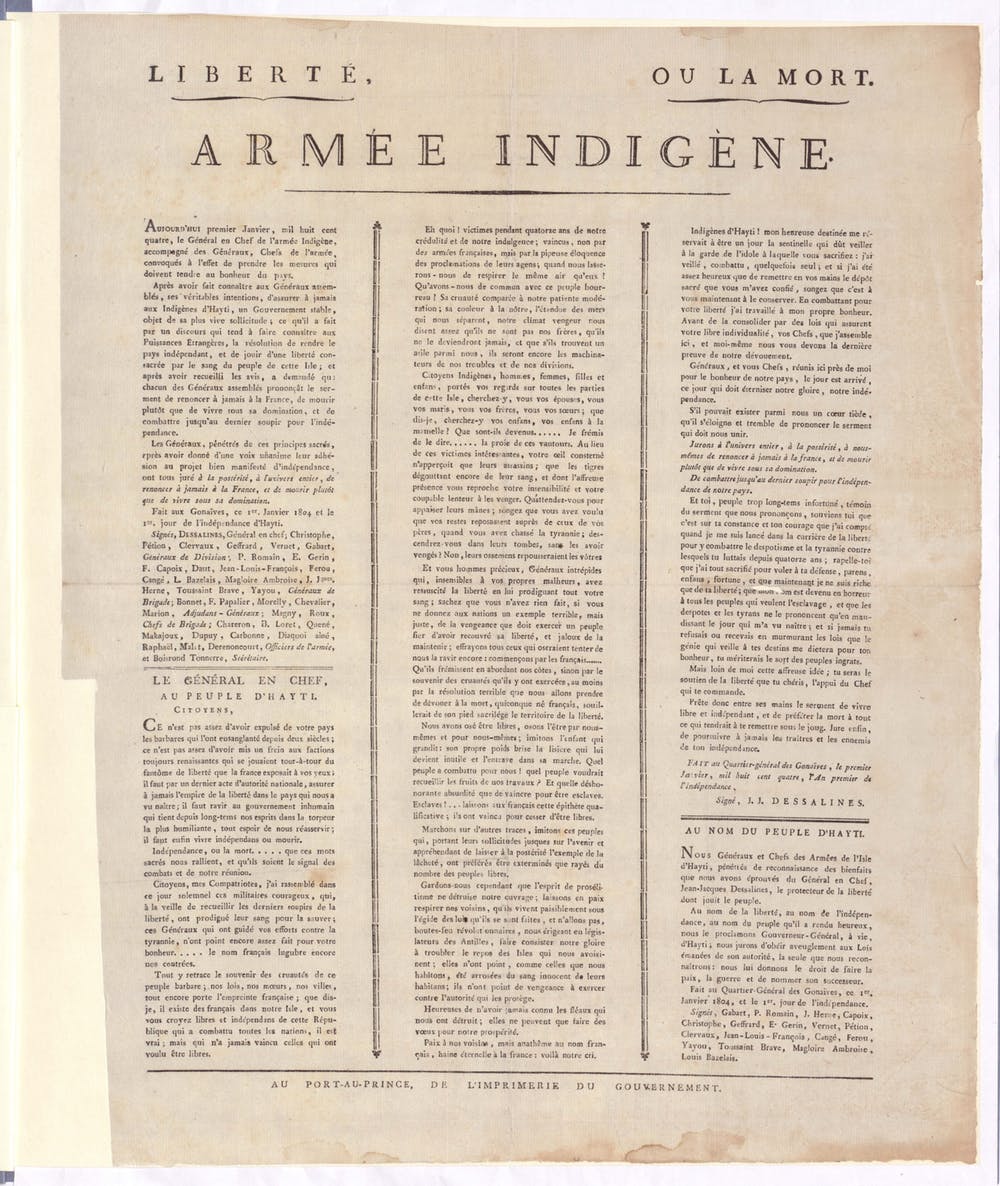

This radical vision of black empowerment is evident in Haiti’s 1804 Declaration of Independence, signed by Dessalines. In 2010 I located the only known extant copy of this stunning founding document, at the National Archives of the United Kingdom.

The 1805 Constitution that followed reaffirmed the abolition of slavery in Haiti, making it the first free black state in the Western Hemisphere.

It also eliminated official racial distinctions. According to Haiti’s Constitution, all Haitians, regardless of skin color, would be considered black in the eyes of the law. In Dessalines’ philosophy, race was an ideological concept. By securing Haitian citizenship, a person became black.

Under Dessalines’ rule, blackness was to be the source of freedom and equality – not bondage.

Haiti’s rejection on the world stage

Dessalines’ revolutionary fervor earned him international diplomatic isolation.

France refused to accept Haitian independence until 1825, when Haitian President Jean-Pierre Boyer agreed to pay 150 million francs – equivalent to US$21 billion today – for the loss of human and territorial “property.” To ensure compliance, French warships with loaded canons threatened the country from the harbor of Port-au-Prince.

Things also went badly for the newly independent Haiti in its own neighborhood.

Jefferson imposed an embargo on Haiti, cutting off trade with the country from 1806 to 1808, and the U.S. refused to recognize Haitian independence until 1862.

Dessalines was assassinated in 1806 by opponents within his own government.

A modern black hero

The international smear campaign almost succeeded in erasing Dessalines’ revolutionary legacy.

As one opponent to the Little Haiti street renaming claimed, Dessalines is “obscure to most Americans.”

Even within Haiti, Dessalines is overshadowed by the black Haitian military leader Toussaint Louverture, allegedly a more restrained and diplomatic revolutionary.

But as scholars have revised the long-dominant racist narrative about Dessalines, public interest in the abolitionist has grown.

As the Haitian-American New York Assemblywoman Rodneyse Bichotte said in Brooklyn, the newly named Dessalines Boulevard is “undoing in a concrete and tangible way centuries of the trivialization of our history.”

Julia Gaffield is an Assistant Professor of History at Georgia State University. The original version of this article was published by The Conversation.