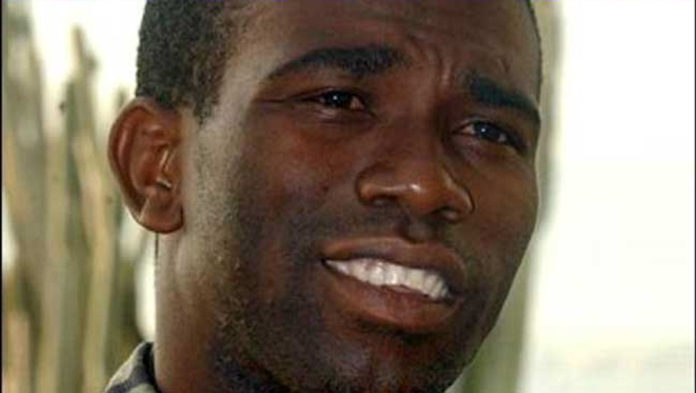

For eleven years, the U.S. attempted all manner of ruses, persuasion, negotiations, and ambushes in an attempt to capture paramilitary leader Guy Philippe after a Miami grand jury issued a November 2005 indictment against him for drug trafficking and money laundering. But it was all unsuccessful until he left the rural, seaside Haitian town where he was holed up and ventured into the capital.

Acting U.S. Attorney Benjamin G. Greenberg enumerated the efforts of Haitian and U.S. authorities to apprehend Philippe, 49, in a Mar. 10 response to his lawyer’s motions to dismiss the charges against him because too much time had elapsed between the indictment and his Jan. 5, 2017 arrest by Haitian police. Philippe, through his attorney Zeljka Bozanic, also claimed he was unaware that he was being pursued, a contention the U.S. calls “patently false.”

Greenberg also refuted Philippe’s assertion that he enjoys parliamentary immunity and that he was mistreated after his arrest.

Interestingly, however, Greenberg did not contest Philippe’s claim that in April 2006 he visited the U.S. Embassy in Haiti, where they made no effort to arrest him. Furthermore, the U.S. State Department has not responded to Haïti Liberté’s inquiries about the veracity of Philippe’s claim.

In early 2006, the U.S. gave Philippe “a travel authorization letter” to “lure [him] to the United States,” but “that travel did not occur,” Greenberg wrote. It is not clear how the letter was given to Philippe or if it was delivered to him at the U.S. Embassy.

Greenberg also outlined a “highly publicized” July 2007 raid on Pestel “involving multiple helicopters,” followed by another on Mar. 28, 2008. Authorities then laid siege to the area for about a week, setting up “checkpoints” and offering “payment for information leading to [Philippe’s] arrest.”

Another armed raid was attempted on May 14, 2009, involving a “foot chase” where Philippe “absconded into an area of dense vegetation.” Another “extensive search” took place around Pestel from Jun. 26-29, 2009, but again it failed.

A fourth raid was attempted on Jun. 22, 2015, according to Greenberg, but “agents came upon a roadblock and were forced to abort the mission.”

Nonetheless, the pursuit had apparently rattled Philippe. In August 2007, Philippe’s attorney contacted the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) to say he “would surrender… if the United States agreed in writing that he would serve less than three years in prison and that the money laundering charges would be dropped,” Greenberg wrote.

Philippe spoke directly to a DEA agent on Apr. 9, 2008, asking “how he would depart [Haiti] if he surrendered at the United States Embassy,” the U.S. Attorney explained. The next day, Philippe’s wife spoke to the agent, asking about Philippe’s “potential sentence and location of incarceration if found guilty.” Philippe again spoke to a DEA agent on Apr. 17, 2008, the U.S. Attorney wrote, saying “he was going to surrender himself to the United States Embassy as soon as his wife was prepared to go” and proclaiming “I am a man of my word.” He said he needed “a week or two,” and then in August 2008 told the DEA “he was ready to surrender in a few days. He did not.”

In January and February 2009, there was another flurry of unfruitful contacts and negotiations between Philippe and the DEA, according to Greenberg. On May 26, 2009, Philippe even allegedly contacted an “FBI agent directly” to say that “he was willing to turn himself in as long as he was treated respectfully.”

Guy Philippe postured as a defiant nationalist, a mythic Zorro-like character, but he “personally reached out to various [U.S.] agents over the course of the last eleven years to discuss his surrender to the United States,” Greenberg wrote. Philippe never made a deal because he “wanted to avoid prosecution.”

The U.S. Attorney also dismissed Philippe’s claim that he enjoyed parliamentary immunity, saying that the former police chief and “rebel” leader “misrepresents his status as a Haitian senator” being merely “a Senator-elect waiting to assume office” and thus “not entitled to immunity under the Constitution of Haiti.”

As for Philippe’s claims that one of his security guards was wounded by two bullets during the arrest, the U.S. contends that “no injuries were reported by anyone.” Furthermore, contrary to Philippe’s assertions, he “was not hooded at any time” and “was transported in an air-conditioned Chevrolet Suburban” for most of the six hours between his arrest around 4 p.m. and being put on a U.S. plane to Florida around 10 p.m..

In her Feb. 28 motion, lawyer Bozanic had claimed that Philippe had been “forced to sit on a very hot floor of the vehicle as the engine was right underneath him [sic]… without any food or water.”

In response, Greenberg said “Chevrolet Suburbans have the engines at the front of the vehicle, not beneath the floor,” and that when Philippe said he was hungry, “the defendant was given water and a granola bar,” saying “he was okay” and “joking around” with U.S. agents.

The U.S. also completely rejected Philippe’s claims that he was targeted for death and mistreated with “outrageous” conduct as “unsubstantiated.”

Guy Philippe, originally a soldier in the disbanded Haitian Armed Forces, became a prominent police chief who fled Haiti after he was discovered to be planning a coup d’état against former president René Préval in 2000. Based in the Dominican Republic from 2001, he led a few hundred “rebels” in launching deadly attacks in Haiti for three years to oust former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide, whom the U.S. Embassy, backed by a Navy SEAL team, forced into exile on Feb. 29, 2004. Philippe ran for president in 2006, receiving less than 2% of the vote. But he won a Senate seat in an anemic 2016 election, where less than 20% of the electorate turned out.