On August 7, Laurent Saint-Cyr, the one-time head of the American Chamber of Commerce in Haiti, was sworn in as president of the Transitional Presidential Council (TPC). He is set to lead the council through the end of its mandate in February 2026.

With the position of prime minister held by fellow businessman Alix Didier Fils-Aimé, and no elected officials holding office at any level, the government is directly in the hands of the private sector — a first in the recent history of Haiti, a country with some of the highest inequality rates in the world and where oligarchical state capture has hampered development for centuries.

“Private sector actors played a role in creating this chaos,” Fritz Alphonse Jean, an economist who held the rotating presidency of the council prior to Saint-Cyr, told Ayibopost. “When the private sector controls both branches of the executive, it raises legitimate concerns.”

The week prior, there were allegations of attempts to thwart the transfer from Jean to` Saint-Cyr or even to remove the prime minister — stoked by a social media post from the U.S. State Department referencing vague reports of “bribery.” Jean denied any untoward attempt at blocking Saint-Cyr or removing File-Aimé, even while acknowledging his concerns over the private sector’s consolidation atop the government. But the US statement sent a clear message: the US was once again picking sides in Haiti’s internal politics.

Notably, the ascension of private sector actors in the political space is taking place at the same time as perhaps greater than ever scrutiny of those same actors. Beginning with the 2022 imposition of a UN sanctions regime, myriad UN reports have focused on the role of Haitian oligarchs in financing and providing weapons to armed groups, and on corrupt practices such as customs and tax avoidance, drug trafficking, bribery, and general state capture. Canada, going further than any other nation, has implemented individual sanctions against several high-profile individuals from the private sector.

In July, the Trump administration arrested Haitian oligarch Reginald Boulos, who had been living in Florida, alleging that he had “engaged in a campaign of violence and gang support that contributed to Haiti’s destabilization.” Like many among the Haitian elite, Boulos is a U.S. Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR). In an unprecedented move, Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced that the U.S. would initiate deportation proceedings against any LPR found to be supporting Haitian gangs. Boulos’ deportation proceedings are ongoing. The action set off speculation that the U.S. would target additional Haitians under similar grounds.

The two superficially contradictory developments — the consolidation of the private sector’s hold over government and the targeting of the private sector for sanctions and law enforcement action — have set off a wave of DC-based lobbying activity in recent months.

In February, Prime Minister Fils-Aimé hired Carlos Trujillo, a former Trump administration official, as a lobbyist. The 12-month contract — which covers the remainder of the transitional government’s mandate — includes a monthly base payment of $35,000. But the Haitian state is not the only entity staffing up with DC-based lobbyists.

In March, a US-registered corporate entity controlled by the notorious Deeb family hired Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, one of the largest lobbying entities in the country, to represent its interests in Washington. Reynold Deeb, one of three brothers involved in the family business, has been sanctioned by Canada and singled out by the UN for allegedly criminal actions. The family, which is the largest single importer in Haiti, spent $110,000 on lobbying services through June.

There are some indications the lobbying is paying off. In July, the U.S. Department of Agriculture led a trade mission to the Dominican Republic aimed at boosting U.S. exports. One of the “US companies” that participated, U.S. Agricom Inc., is run by the Deeb family, according to Florida state corporate records. Olivier Acra, brother of the sanctioned Marc-Antoine Acra, alsoparticipated in the mission. The Acras are one of the biggest importers of rice into Haiti — one of the largest markets in the world for U.S. rice.

In April, a Florida law firm, Patino & Associates, hired Checkmate Government Relations, to engage on “policies related to business and trade between the U.S. and Haiti.” Though it is unclear on whose behalf the law firm is working, in 2021, Patino & Associates was a registered lobbyist for Haiti’s U.S. embassy. In a little under three months, the firm spent at least $300,000 on lobbying activity.

But perhaps the biggest development has been the formation of Institut Macaya, a “think tank” run by a coalition of 18 individuals from the private sector. In April, the group hired TSG Advocates DC, the DC wing of one of Florida’s biggest lobbying shops — which saw a boon to its business with the election of Trump and elevation of politicians with Florida ties within his administration. Macaya spent some $30,000 over the first two-plus months of the contract. When PM Fils-Aimé traveled to Washington earlier this summer, a delegation from Institut Macaya was also in town on a parallel visit.

“They are trying to become the voice of the private sector,” a source with knowledge of the group’s operations explained in an interview. “They want to change the perception of the private sector because the whole world still thinks of them as the Morally Repugnant Elite.”

The term was coined in the early ‘90s when many of Haiti’s elite families backed a brutal military junta that had overthrown the country’s first democratically elected president. Dozens of families faced U.S. financial sanctions.

Institut Macaya arose out of initial meetings held in Florida in the summer of 2022, as the U.S. began openly talking about sanctions as a response to escalating violence in Haiti. That October, the UN Security Council established a sanctions regime aimed at targeting the support networks of Haiti’s armed groups. Shortly thereafter, the US, Canada, and others began implementing individual sanctions and pulling visas.

the long-standing relationship that Haiti’s private sector has with U.S. politicians and diplomats continues to be a significant driver of policy in Haiti.

“In anticipation of sanctions, some members of the private sector, including Reuven Bigio, who chairs his billionaire father’s GB Group conglomerate, have been meeting in Miami and Haiti under the auspices of a new entity called the Macaya Group,” the Miami Herald reported at the time. Institut Macaya’s website was registered just days after Reuven Bigio’s father, Gilbert Bigio, was sanctioned by Canada.

Macaya took on a prominent role in the political negotiations that took place throughout the tenure of de facto prime minister Ariel Henry. Macaya — or at least some members of Macaya — played an active role in bringing Jonathan Powell, UK prime minister Tony Blair’s former chief of staff, into the discussions as a mediator. Though Powell never disclosed who was paying him, he traveled regularly with a top official in the Bigio family conglomerate, according to multiple sources.

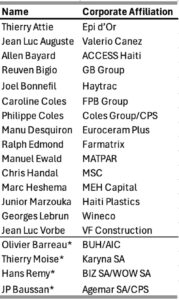

After the fall of Henry in early 2024, the “private sector” was one of the nine sectors chosen by the international community to participate in the resulting TPC. The sector’s eventual choice was Laurent Saint-Cyr. For 15 years prior to his appointment, Saint-Cyr had worked for Alternative Insurance Company, whose CEO, Olivier Barreau, was among the original backers and participants in Institut Macaya — though he has since stepped down from the group for personal reasons. Barreau is expected to be a candidate whenever an election is eventually held. (While the group has not made the full list of its members publicly available, a complete list is provided below.)

Barreau is also the head of Banque d’Union Haitienne (BUH), a private bank. Christopher Handal, another member of Macaya, is also on the BUH board. Prior to becoming prime minister, Fils-Aimé sat on the board of BUH as well, revealing the close business and social connections of those atop the government with Macaya. On the bank’s board, Fils-Aimé replaced Eddy Deeb, who had been removed the year prior after his brother Reynold Deeb was sanctioned by Canada. According to a source close to Institut Macaya, it was a conscious decision to not include any of the Deeb family among the formal members of the group. Macaya’s office space, however, is in the Royal Oasis hotel, in which Deeb is a major investor.

Several other major importers are not present among the group’s official members, including the Zreiks, Acras, Khawlys, and Saiehs.

In 2014, a few key Institut Macaya members were involved in a similar effort, called Haïti Chérie. In addition to Reuven Bigio and Christopher Handal — both involved in Macaya — Haïti Chérie also included Allan Zuriak, Sherif Abdallah, Marc-Antoine Acra, and Steeve Khawly. Canada has since sanctioned the latter three. Though Haïti Chérie was framed at the time as an effort to distinguish the younger generation of elite, it ended up mostly as means for members to channel political support to the Parti Haïtien Tèt Kale (PHTK), the party of former presidents Michel Martelly and Jovenel Moïse. The first executive director of Institut Macaya was formerly the director of Haïti Chérie, though he was replaced last year.

“It’s clear the private sector has a bad reputation both locally and internationally,” Jean-Paul Faubert, Macaya’s new executive director, told me in an interview. “It’s not through words that we will change that, it is through action,” he said.

Part of Institut Macaya’s narrative in support of a new, enlightened oligarchy has been its focus on a 10-year development plan for the country. In November 2024, the organization published a 36-page document on its website titled “A Better Haiti for All,” which outlined a series of guiding principles.

“Since our independence, our nation has suffered from the absence of a real social project and vision focused on collective and sustainable emancipation. It lacks solid foundations, effective governance and an economic orientation capable of supporting the freedom so desired by our founding fathers,” the report’s introduction states.

“Haiti is a country that needs to be rebuilt,” Faubert explained. “No foreign nation will come to rebuild Haiti for us, Haitians have to step up, the economic elites have to assume their responsibility, just like in any country, to put the country on the right path,” he said.

In early August, with Saint-Cyr’s ascension to the head of the council just days away, Institut Macaya hired a U.S. consultant, Andrew Cheatham, to come up with an action plan, according to Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA) paperwork filed with the Department of Justice.

“I am working as an expert advisor for the drafting of a Haiti Action Plan. This is a 20–25 page document that proposes activities in the areas of Security, Governance and Political Transition, Economic Development (infrastructure) and Humanitarian assistance to support Haiti’s stabilization,” Cheatham’s filing states. He notes that he is being hired by a consulting firm retained by Macaya for eight days at a rate of $850 per day.

On the one hand, the hiring of Cheatham makes sense. In 2023, he wrote an article for his former employer, the U.S. Institute of Peace, about the key role of private sector actors in achieving peace in conflict settings. He specifically mentioned the development of Institut Macaya. “Organized and serious, this group of Haitian business owners are a valuable asset that should be capitalized on by the bigger ecosystem of players — including multinational enterprises — looking to resolve Haiti’s ongoing crises,” he wrote.

But a group of wealthy individuals spending a little less than $7,000 to come up with yet another plan struck some as an indication that the term “elite” is being misused. “18 People from the private sector are unable to come up with an action plan for Haiti?” asked Monique Clesca, an activist and member of the Montana Accord, on social media. “This says a lot about the mediocrity of this sector,” she posted on X. “That they hired a foreigner to do it also shows the disdain they have for Haitian professionals.”

“It’s normal that some people are skeptical of anything the private sector does,” Faubert said, “I can understand that.” But, he added, “it is a step forward if people admit that past behaviors were not necessarily the right ones and say things need to be done differently.”

“People that do that need to be encouraged and given the benefit of the doubt to show their sincerity,” Faubert said. He described Cheatham’s work as coming up with a short-term roadmap that could lay the foundations for longer-term development. Though, as Faubert acknowledged, it’ll take more than words — or yet another plan — to change perceptions.

Notably, the FARA filing states that the “Action Plan” will be used “by Macaya in meetings to seek assistance for Haiti from the U.S. government, U.S. Congress and other U.S. actors.” In this regard, it echoes a similar effort after the 2010 earthquake, the Private Sector Economic Forum (PSEF).

“For the first time in the history of Haiti, a unified and inclusive private sector …has decided to break with the past and formulate a shared vision and roadmap for the sustainable development of Haiti,” the organization’s inaugural report, released on the eve of the first major donor conference after the quake, optimistically noted. It was written with the support of a U.S. consulting firm.

The PSEF was led by Reginald Boulos and did end up playing a major role in Haiti’s reconstruction — the failure of which is, in many ways, what precipitated the myriad crises affecting the country today. The group’s proposals were clearly evident in the development plan that guided the country’s foreign-aid financed reconstruction, and Boulos sat on the board of the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission led by former U.S. President Bill Clinton. But the Forum also played a political role, working closely with the Hillary Clinton-led State Department to interfere in the 2010 electoral process, resulting in the presidency of Michel Martelly — who has beensanctioned by both Canada and the United States even as he continues to live in Florida.

Despite the rhetoric in recent years from the international community, what is clear is that the long-standing relationship that Haiti’s private sector has with U.S. politicians and diplomats continues to be a significant driver of policy in Haiti. And, despite three years of international sanctions and public criticism of Haiti’s elites, the country’s oligarch class has perhaps never held more power — though of course there remain many internal divisions.

In mid-1994, the New York Times reported on how many elite families, despite being sanctioned by the U.S. and facing an international embargo, had continued to get rich throughout the military junta years. At the time of the article, the Clinton administration had just provided an exemption allowing the trade of certain goods. Explaining the ability of the elite to avoid more significant repercussions for their actions, the Times wrote: “Their influence has been reinforced by personal ties forged with generations of American diplomats and by their use of well-connected lobbyists in Washington.”

Thirty years on, it seems the story remains much the same.

Below is the full list of Institut Macaya’s current members. Those with an “*” were members at one point but are no longer. The corporate affiliation is only a partial accounting as many individuals are associated with multiple entities:

This article is reprinted from the website of the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), where Jake Johnston is the Director of International Research. He is the author of Aid State: Elite Panic, Disaster Capitalism, and the Battle to Control Haiti from St. Martin’s Press.